When the second season of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt returns to Netflix this week, viewers will be reacquainted with its earworm of a theme song. You know the one: With a hefty dose of Auto-Tune, knockout catchphrases like “females are strong as hell,” and jaunty, eye-popping visual effects that match the personality of its titular star, the song crescendos as the shell-shocked optimist Kimmy Schmidt is led out of her underground bunker captivity by a SWAT team. It’s no surprise that a remix of this quirky song went viral itself, garnering more than four million hits. The virality of the song hinges on the emotional delivery of Mike Britt, the actor who plays the neighbor to the show’s cult-leader kidnapper and the women he held captive, an obvious nod to the Ariel Castro case that unfolded in May 2013. Playing alongside video of Britt’s character singing is a split-screen montage of white people in archival footage performing classical music, clapping, and simply looking.

In an interview with Wired, one of the remixers, Evan Gregory, dished that he and his team had searched news sites for soundbites they use to “songify” the news, which is a word he and his siblings, known collectively as The Gregory Brothers, coined to describe their brand of remixing. “Seventy percent of our job is scouring websites like the Huffington Post and the Drudge Report, which is really a fate I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy,” he said. Auto-Tune, the de rigueur audio effect of internet remixers, is used heavily in “songified” news because it mechanizes the human voice, thereby turning vocal tinges of fear and other heavy emotions into cheer. This whole process essentially turns segments of the 11 o’clock news into viral jams, stripping away tragedy to create fun pop.

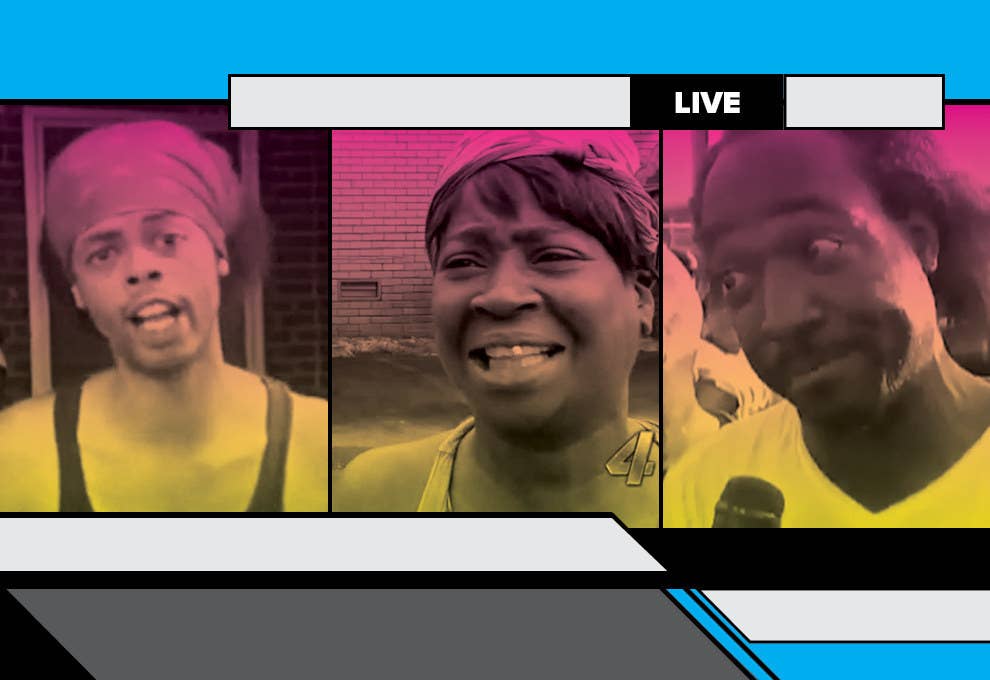

What he didn’t say is that Britt’s portrayal is refracted through viral news reports of Antoine Dodson, Sweet Brown, and Charles Ramsey. These videos are several years old and have been discussed at length in the pop culture sphere, but because new videos, like those featuring Michelle Clark, Michelle Dobyne, and Hazel London continuously make headlines, the original trio are still potent cultural references, even now. Dodson’s known for giving an interview after he helped thwart an attacker who tried to rape his sister, Sweet Brown for a statement she gave soon after her apartment complex caught fire, and Ramsey for the interview he gave to a scrum of reporters moments after rescuing Castro survivors Amanda Berry, Gina DeJesus, and Michelle Knight. The way Britt’s character is presented (poor, dressed casually, talking off-the-cuff) parodies the viral stars when they were first caught on camera by a news crew. And the Gregory Brothers’ remixes provide a particularly disorienting filter of the white gaze, in that they give a pleasing, innocuous-seeming lift to grave accounts of violence and danger. Think of the Gregorys’ remixes as modern send-ups of blues tunes transformed into dancing ditties, although the songified blues use real-life trauma and lyrics comprised of formal testimony.

Antoine Dodson was the first news interviewee to have his face splashed all over the internet when his video went viral in July 2010. He was interviewed by a Huntsville, Alabama, station about the attack on his sister, when a man climbed into her second-floor window and tried to rape her. The lyrics to the song double as his statement to reporter Elizabeth Gentle (compiled from the original news report).

Well, obviously, we have a rapist in Lincoln Park. He’s climbing in your windows, he’s snatching your people up, trying to rape ‘em. So you need to hide ya kids, hide ya wife, and hide ya husbands cause they raping everybody out here...We got ya T-shirt. You done left fingerprints and all. You are so dumb. You are really dumb, for real...You don’t have to come and confess that you did it. We’re looking for you. We gon’ find you, I’m lettin you know now. So you can run and tell that. Homeboy.

The Gregory Brothers have Auto-Tuned Dodson and Ramsey to great success; the song made out of Dodson’s interview, “Bed Intruder,” charted on the Billboard Hot 100 and subsequently went platinum. And Brown, Ramsey, and Dodson became internet stars alongside grumpy cats, Norwegian comedians, and laughing babies: Ramsey and Brown appeared on national morning shows and TV commercials; Dodson became a Halloween costume. Combined, their videos have been viewed hundreds of millions of times on YouTube. But, while the babies have a chance to grow up and become notable for something else, and the “Double Rainbow” guy is also known as an MMA fighter, in the pop culture realm, Dodson and company are locked in the frames of their original traumatic interviews and the numerous Auto-Tuned pop and hip-hop remixes that have come after. Giving an interview to a news station is customary after tragedy; what’s less common is that people become permanently enshrined for their trauma, unless of course, they’re black. The ways trauma is repackaged quickly after interviews are recorded is a result of our fast-moving media cycle. And it’s true that black internet stars have talked to news reporters in memorable ways that make them subject to public fascination. But it’s also true that black viral interviewees hardly had any time to grieve before their feelings were repurposed for the zeitgeist, which is unseemly given how, seen through the mainstream white gaze, black pain has been romanticized (the “race” movies of the early 20th century) or made comical (minstrel shows).

So it’s a little odd that these viral interviewees are called minstrels themselves. Dodson, Brown, and Ramsey have been criticized at length for their statements to news reporters. Writer Fidel Martinez claimed that the videos “are essentially a modern day minstrel show,” and Aisha Harris, writing for Slate, suggested that the popularity of the videos might be due to “a persistent, if unconscious, desire to see black people perform.” Indeed, when Hazel London laments the transformation of the La Bella Noche club into the OK Corral, she’s either called ghetto or uproariously funny; Charles Ramsey’s turn as hero is hampered by claims that his appearance and language make him a coon or minstrel; and Sweet Brown is either a hilarious lady or a mammy figure incarnate.

Black viral interviewees hardly had any time to grieve before their feelings were repurposed for the zeitgeist.

Those original impromptu interviews that ended up across the internet represent the ways black people can be randomly captured in a spectrum of cell phone videos, street cams, and news crews in order to be consumed for entertainment. Much like how rampant use of the word “basic” is an expression of class anxiety, some critical responses to these viral videos are expressions of some black people’s camera anxiety, or fear of surveillance. Tech theorist and inventor Steve Mann defines surveillance as “organizations observing people.” Because the viral news interviewees are taped and originally shared by news organizations, they fall under Mann’s definition of surveillance and it goes without saying that those being surveilled have less power than those behind the camera. He’s even coined a new term, “sousveillance,” to describe what happens when people who are themselves surveilled aim their recording devices at organizations who wield more power.

Simone Browne engages Mann’s concepts of surveillance at length in her book Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. She asserts that blacks have always been under the white gaze. “In the time of slavery that citizenry (the watchers) was deputized through white supremacy to apprehend any fugitive who escaped from bondage (the watched), making for a cumulative white gaze that functioned as a totalizing surveillance,” she writes. “The violence of this cumulative gaze continues in the postslavery era.”

Brown, Dodson, and Ramsey show that even when you speak for yourself, you have to be careful who you’re speaking to.

In this moment of the “postslavery era,” where viral videos are now the norm, it feels necessary to always be prepared to speak on camera, as this blog entry by a business software company, and this one, also by a business blogger, warn.

Beneath their cheery veneer, the remix videos are implicitly a PSA against being unprepared when someone’s camera captures and then places you under that “cumulative gaze.” Even though camera anxiety has manifested via fear of viral videos, it’s not a new phenomenon; the tradition of drylongso, or ordinary, black testimony, shows that surveillance and the manipulation of our images have always been persistent problems for American black people. Brown, Dodson, and Ramsey show that even when you speak for yourself, you have to be careful who you’re speaking to.

In his 1903 opus The Souls of Black Folk, African American philosopher W.E.B. Du Bois describes a phenomenon called double-consciousness.

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness--an American, a Negro, two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

Under double-consciousness, black people struggle with two separate perceptions: how whites see them, and how they see themselves. Writing for the Huffington Post, Rev. Charles E. Williams II placed the perception of the Sweet Brown and Charles Ramsey videos in a tradition of double-consciousness. He wrote, “So yes the response that trivialize[s] the contribution and especially the heroic effort of Mr. Ramsey is racist. However, if you are like myself you laugh not in ridicule or disgust but laugh because they have learned not to slip into their other character and speak just as colloquially as Brown and Ramsey, which is to say without reserve.”

The term viral, in one reading of these responses, has a double meaning. It suggests black pathology, or black people’s innate dysfunction. What it means to actually know these people, after or in spite of seeing them online, is still obscured, even for black viewers, because the videos take on lives of their own. It’s difficult to find the original interviews on YouTube, since they’ve been copied and manipulated countless times by remixers. Consider this flip: The line “I was attacked by some idiot out here in the projects,” spoken by attack survivor Kelly Dodson, is a bright, Auto-Tuned adlib on the “Bed Intruder” song that builds to the song’s bridge, as Antoine Dodson’s phrase “so dumb” is repeated several times. The editing reduces her comment to a simple, trite soundbite divorced from the details that ground the viewer in her in reality: the trash can the intruder used to hoist himself up to her room, the shattered glass on her bedroom floor, the baby she gestured toward, who had been sleeping next to her when the man broke in. We just hear “idiot in the projects,” and then “so dumb,” which is maybe a connection we’re supposed to make.

“We are a nation primarily because we think we are a nation.”

Although they’ve been framed within double-consciousness, Dodson, Brown, and Ramsey have never been placed in the drylongso tradition, of black people speaking directly and without the reserve that Williams mentions. Drylongso means “ordinary,” according to John Langston Gwaltney, the anthropologist who edited the book Drylongso: A Self Portrait of Black America. The term is referenced in blues songs by Robert Johnson, Skip James, and King Solomon Hill, among others. In his book on blues speech, Steven Calt briefly traces the etymology of drylongso from meaning “for no good reason” in blues songs, “fate” in ‘30s Harlem, and “ordinary” in present-day speak. In Drylongso, Gwaltney interviewed 47 everyday black Americans and compiled their often candid, humorous, and critical testimonies of life in America into this anthology. The viral interviewees are a part of this tradition, though at a considerable distance that technology has made plain.

Drylongso follows in the footsteps of novelist and pioneering black anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston’s ethos, that it’s important for black people to collect each other's’ stories. The book, Gwaltney writes, “stems from my long-held view that traditional Euro-American anthropology has generally failed to produce ethnographers who are capable of assessing black American culture in terms other than romantic, and from my belief in the theory-building and analytic capacities of my people.” It’s compiled of first-person testimonies of black people that range in age from teenagers to the elderly. The respondents wax poetic on life in America, black nationalism, racism, sex, intraracial dynamics, and rich quotidian experiences that demonstrate what the anthropologist calls “core black culture.” Core black culture, in his view, is made up of everyday black Americans who are neither rich or bourgeois, financially or in spirit. Hannah Nelson (not her real name), a 61-year-old piano teacher, sums up Gwaltney’s project: “Our speech is most directly personal, and every black person assumes that every other black person has a right to a personal opinion.” Nelson’s entire testimony is rife with these philosophical musings that come to define the idea of black culture. “We are a nation,” she tells Gwaltney, “primarily because we think we are a nation.”

Gwaltney conducted his interviews in the mid-1970s, in his old neighborhood in New Jersey. Many of his interviewees organized informal gatherings in their homes, and Gwaltney would talk with them there. “I wanted both the contexts and venues of interviews and folk seminars to be as informal and removed from officialdom as possible,” he writes in the introduction. He wanted participants to feel free to speak honestly, so he changed the names of all of the people he talked with. Although he disdained “officialdom,” Gwaltney also wanted to avoid man-on-the-street interviews, writing that the street corner is “no place to consort with the soul of a great and subtle people living under conquest conditions.” He flat out denounces those kind of interviews elsewhere in the book, saying that Drylongso is not another collection of “street-corner exotica.” The viral news interviews of the 2010s don’t exactly fit Gwaltney’s standards because most of them are collected on the street, but he admits in the book that from his POV in anthropology, he’s not the only authority on the matter. Although the viral news reports might be “street-corner exotica,” his own interviews are not without issues.

“I think this anthropology is just another way to call me a nigger,” a man named Othman Sullivan told Gwaltney. “I’ll talk to you all day long, Lankie, but don’t interview me,” Lucy Ann Melton responded in kind. The difference between talking and being interviewed is a distinction that proves critical for both Melton and someone like Sweet Brown 40 years later. Whether or not the white gaze is filtered by the exoticizing eye of anthropology, the “officialdom” of news stations, or the fun pastiche of the Gregory Brothers, it ends up acting as a form of surveillance. Explaining why he didn’t include talking heads in his documentary Dreams Are Colder Than Death, which focuses on black life in America 50 years after the March on Washington, the filmmaker Arthur Jafa said that “the camera functions as a surrogate for the white gaze and [black people] put on these survival modalities.”

The viral interviews are not the only contemporary cultural products that can be put in the drylongso tradition. Rooted in a similar theme, the protagonist of Cauleen Smith’s film Drylongso is a young black woman who takes Polaroids of black men on the streets of Oakland. And director Kahlil Joseph’s short m.A.A.d., which is inspired by and scored to music from Kendrick Lamar’s album Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, utilizes images of everyday black Americans in Compton to powerful effect. The closing montage, set to Lamar’s song “Sing About Me,” in which the rapper speaks from the perspective of two Compton associates, features portraits of black people at convenience stores, parking lots, and beauty parlors.

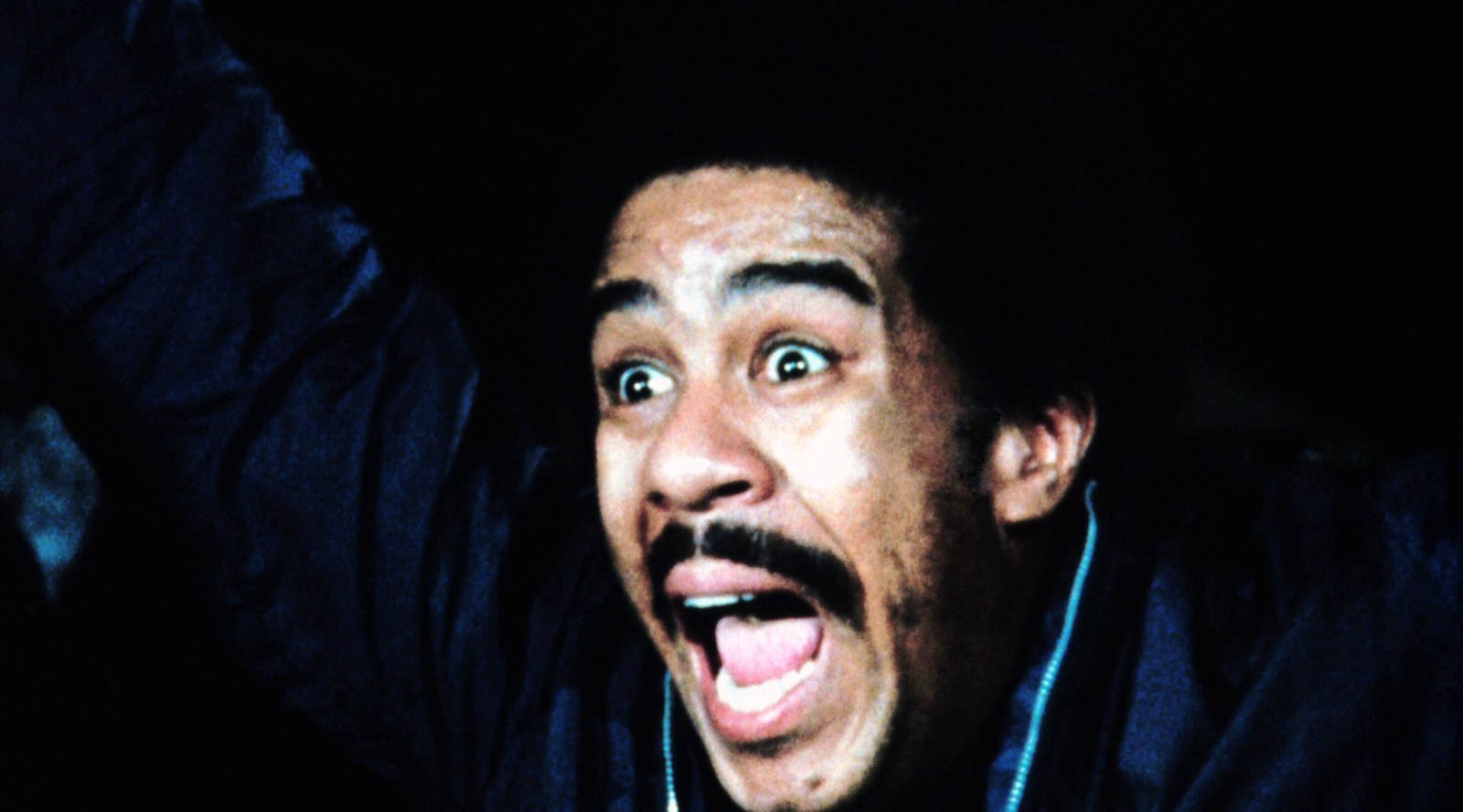

Another visual counterpart for Gwaltney’s Drylongso is Mel Stuart’s landmark concert film Wattstax. Wattstax begins with Richard Pryor shrouded in darkness, and then The Dramatics’ “Whatcha See Is Whatcha Get,” plays during the film’s title sequence. Wattstax is dynamic for how much screen time ordinary black people from Watts get to talk about subjects as vast as natural hair, the government’s treatment of blacks, dating, and when they first realized they were black. Pryor plays a kind of chorus who anchors the film, maintaining humor throughout. Pryor’s presence is significant because both he and the concert scenes balance the film’s heaviness, which is a model of showing black humor in the face of trauma. Stuart, though white, doesn’t omit the references to historical pain and erasure by playing up the music, so the film remains a testament to balance in the documentary form. There are jokes and drama intensified by the camera’s presence; uplifting gospel contrasted with gutbucket funk; the noise of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum cut with moments of silence created by people in deep thought.

It seems no coincidence that Stuart chose to play “Whatcha See Is Whatcha Get” over images of black people doing mundane things; the choice may be a racist articulation of the film’s theme, that what you see in these people is what you get, that they are easy to understand because their words and presentations are so basic, that they represent a kind of authenticity. I see that, and also read the lyrics “what you see is what you get,” originally a man’s romantic plea, as a theory of our viewing consumption of viral interviews. What we see in Dodson, Brown, and Ramsey (mammy, ghetto, hilarious, minstrel, etc.) reflects what we want to get from them, and the lasting messages we take away from their interviews.

Returning to Hannah Nelson’s claim, that “we are a nation primarily because we think we are a nation,” is crucial to understand a constant in black culture: the white gaze. Black nationalism, not race, seems to be contingent upon shared experiences or at least a collective perspective, and I don’t think we’ve had a unified view since the civil rights movement, if then. However, the repetition of respectability in the critiques of the viral videos, or that black people should be aware of how they present to the world at all times, is proof that perception continues to be an issue many black people navigate. Perhaps the long-standing suspicion of the white gaze and its surveillance is one last remnant of Gwaltney’s core black culture, even in the digital age when the vast number of different voices online show a mix of black points of view. In this way, it’s easy to read the finger-wagging of respectability-minded black people as also a beckoning toward close-held knowledge. They are watching you. Black conservatism in this light could possibly have a dual purpose: to scold, yes, but also to hold.

With our fingers on the share and retweet buttons, we become complicit in the surveillance of these black people.

The comments made by Elizabeth Gentle, from a follow-up interview with Dodson days after the initial video, address some of the responses the station received for airing the clip. “Now some have contacted our newsroom saying that interviews with people like Antoine reflect poorly on the community. To that, I say censoring people like Antoine is far worse.” For sure, censoring Dodson is terrible, but what about the ways the news report videos are distributed? That may be far worse. News cameras aren’t the primary tools of surveillance. With our fingers on the share and retweet buttons, we become complicit in the surveillance of these black people, by spreading their manipulated images around. Forget going viral, these videos are metastasizing.

No one knows the ups-and-downs of internet stardom quite like Antoine Dodson, whose life has been a whirlwind of celebrity and notoriety following his initial fame. A recent video from Dodson’s Instagram page shows him coping with his post-fame life as a school worker, still dogged by his claim to fame: “I made it to 800 followers, yay woohoo. I’m a fucking celebrity,” he said, mean-mugging the camera. The way he delivers that line makes you think that “fucking celebrity” is a special designation made for him, Ramsey and Brown — meaning one who is still visible but mired in some of the same class-based circumstances that made them famous. After Dodson performed “Bed Intruder” with Michael Gregory at the 2010 BET Hip Hop Awards, comedian Mike Epps joked, “I know that was messed up, but they was able to buy they mama a house and get them out the projects with that song right there. I don’t know how long they gon’ live there...” In 2014, Dodson boxed the alleged “bed intruder” in a match hosted by Kato Kaelin, an event that seemed to confirm Epps’s theory that Dodson’s trip out of the hood would be short-lived.

Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt is about a character, who, much like Antoine Dodson, transitions from her old community into a new one. The line “Unbreakable! They alive dammit” stands out so much in the Gregorys’ remix because it seems to call back to the other videos they’ve flipped; the infallible spirit of black survivors seems to be the main theme of their songs. In the Gregorys, Kimmy Schmidt’s producers hired the right remixers because their brand is synonymous with that kind of triumphant flip. They’ve even taken one of the oldest viral videos and spun it slightly differently.

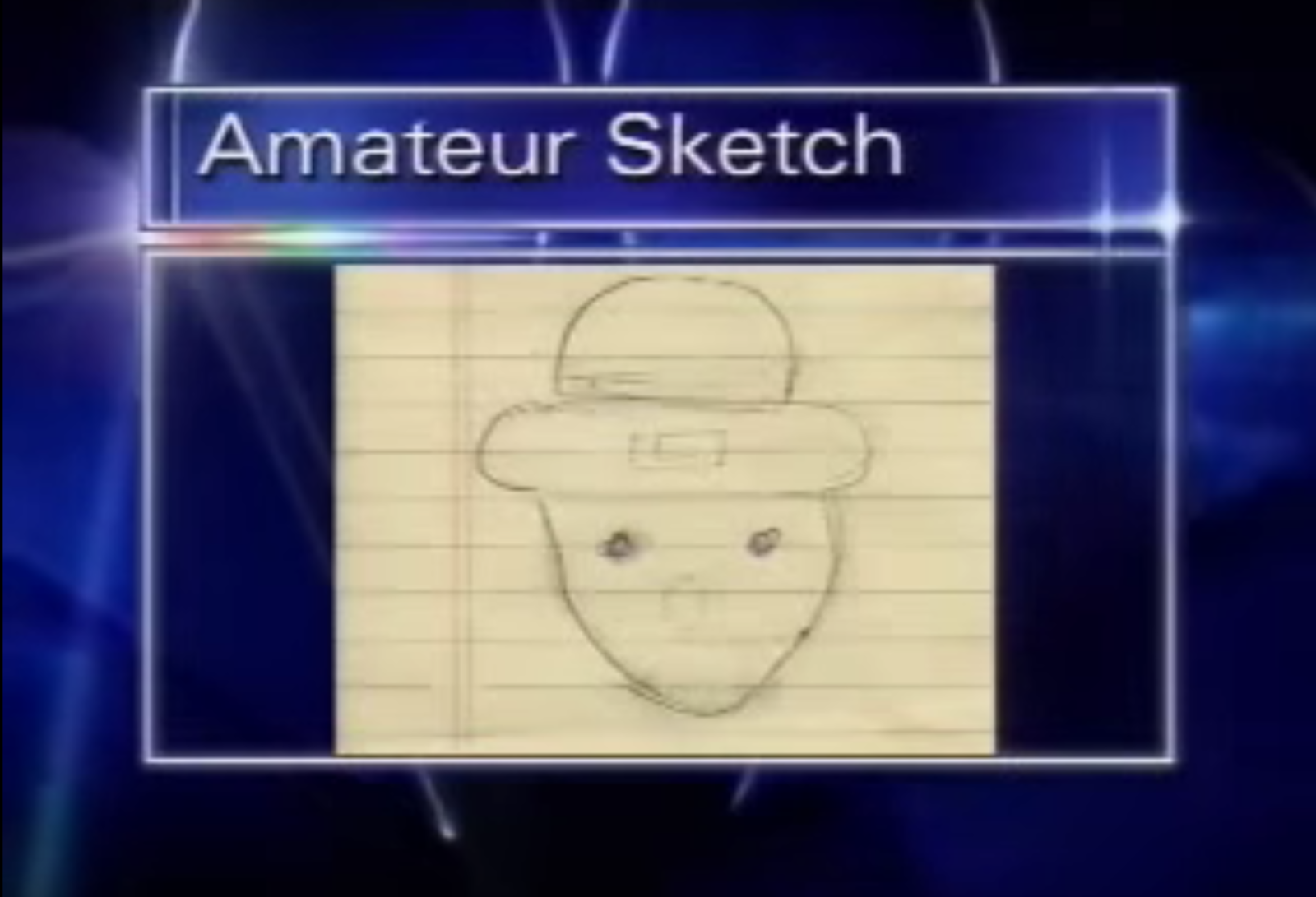

The “Crichton Leprechaun” meme is one of the first viral sensations of the YouTube era, and caused a stir when it debuted in March 2006. The meme is a news report of black residents in the Crichton section of Mobile, Alabama, discussing a mythic leprechaun many residents say is hiding in a tree. It’s been viewed over 25 million times, no doubt helped by the “amateur sketch” of the leprechaun, which is hilariously a nondescript, badly drawn face under a leprechaun’s belted hat. The video is funny largely because the black people of Crichton speak in their own voices about the nebulous, elusive figure. Some say it’s a leprechaun, while others think it’s a crackhead. The shape-shifting “leprechaun” is oddly enough a metaphor for the imprecise, always-shifting ways the videos of Dodson, Brown, and Ramsey, and the others, continue to be viewed years later.

The Crichton meme is a viral video of black people that stings less, because the power of storytelling, though still contained by the news station, is also in the Crichton residents’ hands. With their flip phones aimed at the tree and the news equipment, you see sousveillance in action. It’s black people making their own myths, and reveling in the joy of a spectacle they created. If you watch the Gregorys' Crichton remix, you don’t quite get that. The song, “I Want the Gold,” is typical songified fare: There’s repetition of key lines like “the leprechaun could be a crackhead,” and is free of the glee of the original, accompanied by a guitar riff and a real-life interpretation of the leprechaun, which kills the fun of imagining what the thing is. At the end of the video, the Gregorys hawk their Songify app, crooning “You can songify yourself on the Songify app.” While deputizing us to do their work, the Gregorys are almost always dressed as reporters and anchormen. Their authority is made plain: They don’t want you to forget that their power lies on the other side of the camera.