CAIRO — This October, Uber Egypt partnered with Harassmap, one of the country’s pioneering anti-harassment organizations, to train drivers to fight against sexual harassment — a rarity in Egypt, where sexual harassment of women in Cairo’s chaotic and neglected public transportation is rampant.

“We know that there are big problems here,” Anthony Khoury, general manager of Uber Egypt, which provides only privately-owned cars, a service known as UberX, told BuzzFeed News. “We want to be the safest drivers around.”

Uber Egypt, based in Cairo, committed itself to a zero-tolerance policy against sexual harassment — a phenomenon criminalized under Egyptian law only in 2014, the same year Uber opened here. The move was also savvy branding for the popular car-hailing app, a more than $62 billion franchise, which worldwide has faced waves of legal cases and protests over drivers preying on female passengers and the company’s worker practices.

For Uber users in this megacity — where traffic is notoriously bad and taxis often a hassle — the app is a much-welcomed upgrade to safely navigate daily life. Since October, Khoury said his team has implemented the short anti-harassment training and even suspended and deactivated a few drivers for incidents of verbal harassment, follow-through unheard of with regular taxis, and had no reported cases of physical harassment.

In Egypt’s struggle against sexual harassment, it’s also still a drop in the bucket.

Uber is largely a luxury of the elite — most people in Cairo can’t afford private taxis — and the barriers preventing women from reporting and prosecuting sexual harassment remain terrifyingly tall. Socially it has become easier to talk about sexual harassment since the 2011 revolution, but recently political action has grown harder as crackdowns on activists of all kinds deepen, and the government continues to deny its role in perpetuating sexual violence. And while President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s regime, backed by international funders, has invested billions of dollars in upscale projects in the desert around Cairo — including outlandish plans for a new capital — inside the dense city essential investments in infrastructure to reduce the traffic toll, including safer public transportation, remain largely a mirage.

Khoury, an experienced entrepreneur, acknowledged that in practice “empowering women” in Egypt means much more needs to be done.

“Maybe we are playing a small part,” he said. “But we are playing a part.” He added, “It’s an environment where the culture is quite entrenched.”

Getting anywhere around Cairo can be a harrowing ordeal for women.

Noora Flinkman of Harassmap said Uber had so far been receptive and easy to work with. She was also realistic that many challenges remained.

“Doing the trainings and the partnership and all the publicity, this is the easy part,” Flinkman said. “So we are expecting it to be difficult when more reports come in and how they deal with it. After all it's a business… and we don’t know how much is business and how much is actually real concern.”

Uber’s program developed after the team looked into what they could do to prevent sexual harassment, which a United Nations study estimated (and any Egyptian woman can tell you) basically all women in Egypt experience. Uber then approached Harassmap, which runs a program called “Safe Corporates” to encourage businesses to set a precedent by creating harassment-free spaces for women.

Getting anywhere around Cairo can be a harrowing ordeal for women. The city’s traffic is so bad that the World Bank estimated it eats up 4% of the country’s yearly GDP. Cairo is dominated by private cars, even though only about 11% of the city’s households can afford one. Taxis are considered the safest option for women of means — but still often can entail unwanted advances from drivers, and even physical harassment and rape. Most women depend on the city’s neglected public buses, where they report feeling the least safe, or the chaotic network of aging microbuses and the city’s slowly expanding and internationally financed metro, where in response to attacks in the latter the government instituted two women-only cars instead.

To get anywhere in Cairo you usually need to know the route yourself, a further impediment to increasing the average woman’s mobility. Transportation apps like the popular Bey2ollak track traffic, but so far none have mapped the buses or microbus routes, the latter of which people developed in the absence of government solutions. Two other Taxi apps, the United Arab Emirates–based Careem and Brazil-based Easy Taxi, also operate in Egypt, though neither have initiated a public campaign like Uber. Last year a new initiative, Pink Taxi, started to offer distinctively pink taxis driven only by women for women; critics were not optimistic, dismissing the prices as unaffordable for most women and the gender segregation a bandage rather than a solution.

In ways big and small, women have created their own coping mechanisms. Harassmap, which works to end the social acceptability of sexual harassment by collecting and mapping assaults, started in 2010, back when barely anyone was talking, let alone publicly confronting, the issue. Now, since the 2011 revolution, new groups, like Shoft Ta7arosh [I saw Harassment], Ded Ta7arosh [Anti-Harassment], and Operation Anti-Harassment have sprung up to challenge and change the status quo from within.

Still, the number of women who report sexual harassment is extremely low. Socially, women are usually shamed by police and pressured by family and friends to stay silent because of the stigma against those who acknowledge they’ve been harassed. Legally, the process to prosecute a case is so stacked against the victim that only a few women in Egypt’s history have actually followed through. Last year, a group of human rights organizations criticized the amendments to Egypt’s penal code that specifically criminalized sexual harassment for the first time, calling them insufficient as the government’s “current climate of impunity fuels further crimes,” citing sexual violence against female protesters, detainees, and everyday bystanders. Since a 2013 law banned protests and unlicensed gatherings, efforts by other groups to campaign in public against the phenomena of sexual assaults, mob rapes, and even virginity tests have grown riskier.

A private company like Uber doesn’t face the same pressures as activists and NGOs. Under the partnership, Uber now includes a five- to seven-minute training on how to identify and prevent sexual harassment within a 30-minute training for new drivers, according to Khoury. Drivers hired before the partnership are being brought back in for the anti-harassment training in waves. The training includes basics on what constitutes sexual harassment — from words to touching to worse — as well as setting boundaries like forbidding drivers from asking a female passenger whether she is married and staring at her suggestively through the mirror, all too common taxi etiquette in Egypt.

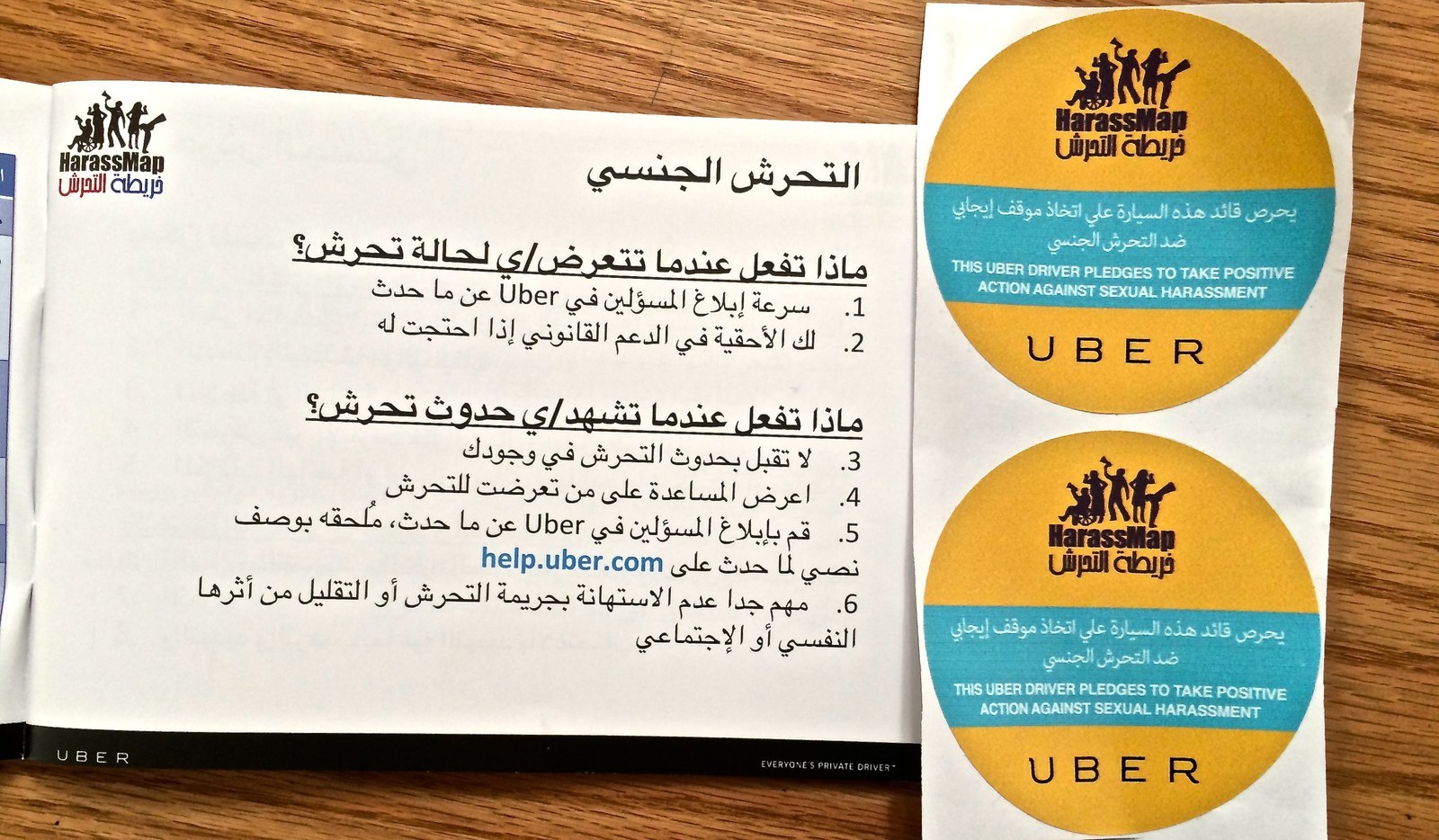

Drivers then sign a pledge and can put a sticker on their car affirming in English and Arabic to “take positive action against sexual harassment.” Drivers must maintain a 4.3 rating to keep working with Uber. If they fall below or receive a series of bad feedback, they can be called in for more trainings or deactivated.

Uber is also providing female drivers an additional three- to five-minute lesson with tips for identifying and defending against sexual harassment. (Female drivers are about 10% of the overall workforce, which Khoury declined to specify.) Khoury said he is looking into ways to increase the number of female drivers and expand the Harassmap partnership past its initial six-month period.

Abdel Fattah Mahmoud, director of Basma [Imprint] Movement, a volunteer anti-sexual harassment movement that started after the revolution, was thrilled to hear Uber was partnering with Harassmap and its Safe Corporates model. Mahmoud also found the short length of Uber’s anti-harassment training “absurd,” suggesting instead it should be at least two to three hours long. For comparison, Basma’s trainings generally run from three to five hours, with additional trainings to be an advocate against sexual harassment structured around a three-day workshop totaling around 18 hours.

Khoury acknowledged that the current political situation and pressures on NGOs “doesn’t help” in confronting the entrenched and intersecting causes of harassment. The success of Uber’s program relies on passengers reporting any alleged incidents, which Khoury said they would then refer on to police if necessary. He said Uber was committed to follow through on prosecuting charges of harassments if such a case ensued.

Khoury also disagreed with the characterization of Uber as only a commodity of the elite: Instead, he said his team had been seeing Uber spread to less affluent areas of Cairo. In December, Uber Egypt started to roll out a trial cash program, making Cairo one of seven of Uber’s over 300 cities to allow customers to pay with cash in addition to credit and prepaid cards. The base fee for cash in Cairo is slightly higher, but Khoury said they made the cash shift in order to expand service — only around 7% of Egyptians have bank accounts, and, of that percentage, many are hesitant to use credit cards online — with particular importance for women without credit and in need of a safe and dependable ride.

Uber driver Amr Nafady, 37, comes from a place where Uber doesn’t commonly go: The father of four lives in Shubra El Kheima, a very dense and poor Cairo neighborhood, where often only tuk-tuks (rickshaws) can navigate the unpaved and narrow roads. Nafady said he was very happy and proud to work with Uber; like the other Uber drivers approached for interviews, he had no problem speaking to a foreign journalist, despite a widespread distrust among many Egyptians in doing so. What he wasn’t happy with was allowing cash-based transactions, fearing it would reduce the quality of customers and service.

Nafady is technically unemployed, along with 40% of Egypt’s Uber drivers, according to Khoury. Uber doesn’t hire the drivers, who are to be contracted through a limo service and undergo background and drug checks to qualify. That means that Nafady doesn’t have any insurance or union and has to pay to keep his car clean and fixed. There’s also really no better option for him: Workers rights in Egypt, one of the instigators of the revolution, still remain far and few.

Nafady agreed that it was important for Uber to raise the harassment issue, though he said he knew to treat passengers respectfully anyway.

“The problem is that if I see someone harassed there” — driving along one of Cairo’s bridges that cross the Nile River, he pointed to the unevenly paved sidewalk where young men and women mingle in the evenings — ”while I’m working and driving you, will I stop?” He shook his head.