Ron Sexsmith is gently strumming his guitar at Plyrz Studios, a hip recording space in Valencia, California, owned and operated by seven-time Grammy-winning producer/engineer Jim Scott. He’s there to put the final touches on his new album, Carousel One (out now), but with his unassuming manner, tousled hair, and casually worn button-down shirt he could easily be mistaken for a member of the production team instead of the star at the center of these sessions. He may not quite look the part, but he’s certainly lived it, and between listening to new mixes he opened up to BuzzFeed News about his life and career, including an amazing encounter that happened during his first tour of England.

“We had a night off, so [tourmate] Chris Difford told me to cancel my hotel and come stay with him at his place out in the country, in Sussex,” says Sexsmith. “On the way there he says, ‘You’ll never guess who lives up there.’ And I was like, ‘Paul McCartney?’ My first guess. And he nods. I ask if he’s ever been up there and he says a few times. And then he goes, ‘Maybe I’ll give him a call tomorrow.’”

In the morning McCartney’s late wife, Linda, invited them over, and only a few minutes later the former Beatle answered the door in his pajamas. He invited Sexsmith and Difford into the kitchen where they discussed music as Linda made the McCartney brood breakfast.

“I was asking him mostly about Wings because that was more my era, and we ended up breaking out the guitars and singing [the Wings’ hit] ‘Listen To What The Man Said’ together."

That’s largely how Sexsmith’s two-decade plus career has gone. You may not know him, but the artists you know and love do. Elvis Costello once said Sexsmith “has got one of the purest senses of melody since Paul McCartney," and Elton John personally called him to praise his 2007 album, Time Being. Even Bob Dylan handpicked a couple Sexsmith tunes to play on his Sirius radio show, Theme Time Radio Hour. And this for a musician who’s never scored a top 40 hit.

“I never set out to be a cult artist,” Sexsmith says while picking at his guitar. “I always wanted to be Elton John or somebody.”

Sexsmith was born in St. Catharines, Ontario, far away from the recording hubs of New York and Los Angeles, and raised in government housing for low-income families (mainly by his mother; his father “wasn’t really in the picture"). From a young age music was his main focus in life, and he quickly earned a reputation as a “human jukebox” thanks to the many cover songs he could play. Whatever inroads he was making toward a career in music, however, were all for naught — at least in Sexsmith’s eyes at the time — when he got a co-worker, Jocelyn, pregnant during a post-high-school summer job.

“She was the first person I ever made love to,” Sexsmith says. “Not only that, but we didn’t know each other. We were tree planters who got drunk one night.”

Sexsmith recalls hearing Bruce Springsteen’s classic song “The River” (with its iconic line “Then I got Mary pregnant and man that was all she wrote”) and crying. “I thought, ‘Well, there goes my music career.’”

A son, Christopher, soon joined the new couple, but their life together was far from easy. “I remember thinking, ‘Here I am with this woman I hardly know, we have a kid, I don’t have any money.’ It was scary.”

In time Sexsmith and Jocelyn fell in love, and later welcomed a second child, Evelynne. It was around this time he realized that fatherhood, rather than being a threat to his artistry, could represent a new start.

“I wrote my first songs when my son came along,” Sexsmith says. “So ultimately I needed that to happen. Because I never wrote before.”

Sexsmith was finding his voice as a songwriter, but he was still many years away from his proverbial “big break.” In the interim he worked as a courier during the day while cramming songwriting sessions in late at night after his family went to sleep. When he finally signed with Interscope Records in 1994, he was a rarity in the music industry — a 30-year-old watching the ink dry on his first major-label record contract.

Mitchell Froom, Sexsmith’s frequent collaborator and the producer behind Crowded House’s first three albums, says he’s never been able to pinpoint why mainstream success eluded Sexsmith.

“There were any number of times I thought we really had a chance,” Froom says. “In some ways Ron’s a bit out of his time. Maybe if he had come up in the '60s or '70s something would have hit big.”

Froom was one of the first producers Interscope approached to helm Sexsmith’s debut album, and he immediately responded to the idea.

“What really got me was the record company sent me this first batch of songs,” he says. “And then I asked to hear all of his new songs — and there were something like 35 songs. There were all these incredible songs they hadn’t even played for people and I thought, Man, this guy is really something else.”

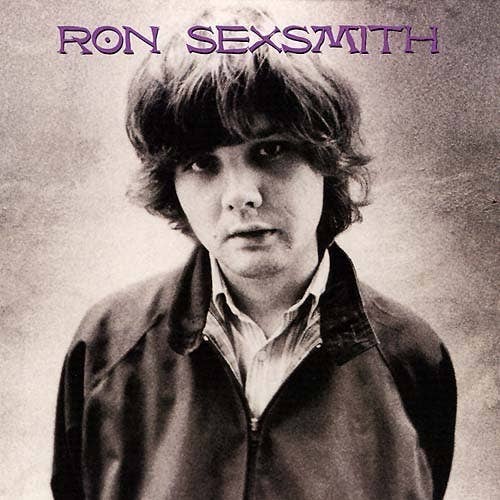

Sexsmith’s self-titled debut — produced by Froom — received high praise from critics, including a 4-star review in Rolling Stone, which deemed the album “a thing of beauty” and enthused that Sexsmith “just may be the most fluent balladeer to come along since Tim Hardin or Harry Nilsson.” Despite this, Interscope only released the album in North America, where it failed to make a splash. “I’d be touring around, and every town I was in I’d go into the record store and maybe it would be in the 'S' miscellaneous section,” Sexsmith says with a shake of the head.

At the end of the year Sexsmith believed Interscope was getting ready to drop him because of his debut album’s poor sales when Elvis Costello appeared on the cover of Mojo magazine holding up the album. This stoked enough interest in Sexsmith that, instead of dropping him, Interscope decided to finally release his album outside North America.

“The whole of ’96 we spent introducing that record to the world, and that’s where I found my audience,” Sexsmith says. “People in Canada didn’t even know me, they thought I was from England or something, so if Elvis hadn’t done that I don’t know where I’d be.”

For his sophomore effort, Sexsmith again worked with Froom with the intention of making an album that would help him cross over into the mainstream. Froom, for his part, had high hopes that the album would yield a hit. “We’d be working on a song and I’d think, Wow. That’s a really catchy song. That’s a great song.” But, like its predecessor, Other Songs received rave reviews but failed to break out.

“I think the label he was on just never really endorsed him enough,” Froom says. “They were always kind of fighting him a little bit, and they were less than enthusiastic with him.” A third Sexsmith/Froom album, the darker-themed Whereabouts, met the same fate.

Whereabouts and the darkness that accompanied it were largely inspired by Sexsmith’s home life, which was troubled by the extended time Sexsmith spent on the road — and his inability to resist its temptations.

“For the first 10 years Jocelyn and I had a really good thing, and then I started touring and being like a clichéd road musician,” Sexsmith says. “I never had my wild twenties, and I felt like I was having my twenties in my thirties.”

Sexsmith’s relationship with his children was also affected by his time away from home. “I was always the ‘kid guy,’ and that was really hard when I started to tour. All of a sudden there was this hole there because there wasn’t someone there to…they sort of had to fend for themselves. I think, looking back, I could have handled things a little better.”

Sexsmith is quick to add that he’s still very close to his (now adult) children, but he clearly hasn’t forgotten those difficult times. One of the new songs on Carousel One, “Can’t Get My Act Together,” addresses how he wasn’t the father he hoped he could be to his daughter when she was small.

“I’ve had a lot of guilt and a lot of regret,” Sexsmith says solemnly. “I mean, Jocelyn was the one who kicked me out. I didn’t want to be the dad who walks out, but I finally got the boot, you know. And I was kind of relieved because I really did think it was for the best.”

As it happens, it was this low point in Sexsmith’s personal life that led to an artistic high-water mark.

Cobblestone Runway (released in 2002) features unlikely touches of electronica courtesy of new producer Martin Terefe, but it was the especially strong collection of songs that really stood out. Two of these songs have gone on to become among Sexsmith’s most covered: “Gold In Them Hills,” a ballad about finding hope in difficult times featuring Chris Martin of Coldplay on vocals, and “God Loves Everyone,” a thought-provoking lullaby written in response to the Westboro Baptist Church’s picketing of Mathew Shephard’s funeral.

Sexsmith says he is now on the Westboro Baptist Church’s hate list for writing lyrics about an inclusionary God who is very different from theirs:

There are no gates in Heaven / Everyone gets in

Queer or straight / Souls of every faith

Hell is in our minds / Hell is in this life

But when it's gone / God takes everyone

“The reaction to the song was positive overall,” Sexsmith says, but there were people — even outside of an extreme group like the Westboro Baptist Church — who took offense.

“I remember doing an interview with someone in Texas and he said, ‘You’re not going to be performing that song down here, are you?’” After a later performance in Chicago, a woman told Sexsmith she would pray for him because she thought he was going to go to hell for writing the song.

“It’s amazing when you have a song named ‘God Loves Everyone,’ which is so positive, and then people take issue with it because they don’t want to know that, or to think that, because they want their heaven to be like a private club where only people who look like them get in,” Sexsmith says.

To promote Cobblestone Runway Sexsmith set off on a world tour in support of Coldplay just as they were becoming one of the biggest bands in the world. At first, the excitement of being part of a tour of that magnitude was undeniable. After years of playing club shows, Sexsmith suddenly found himself singing his songs at legendary venues like Madison Square Garden and the Hollywood Bowl. He was even duetting every night with Martin on “Gold In Them Hills.” “People would go apeshit as he walked out,” Sexsmith says with a laugh.

Another highlight of the tour was getting to know the members of Coldplay. Sexsmith’s long-time drummer and collaborator Don Kerr describes them as “a really great bunch of guys.” Echoing that sentiment, Sexsmith offers details of a night off he spent with Chris Martin in Phoenix, Arizona.

“Chris and I saw in the paper there was an open stage, so we just went down,” Sexsmith says. The impromptu duo performed Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine” in front of what must have been a very shocked group of amateur musicians — plus Gwyneth Paltrow, who was listening from Russia over Martin’s cell phone.

Sexsmith was playing in front of thousands of people every night, hanging out with bonafide rock stars, and enjoying the perks of touring in style, but he couldn’t help but find the experience a little depressing.

“It’s weird when you’re the opening act,” says Sexsmith. “I mean, it’s great you’re playing these places, but when you’re playing Madison Square Garden no one cares and they aren’t there to hear you. After a while you’d rather play a small room full of people who like you rather than a bunch of people who don’t care.”

The tour also drew into stark contrast the financial disparity between a lower tier musician like Sexsmith and an act like Coldplay.

“The funniest memory for me is when we were all eating dinner together,” Kerr says. “Chris was asking Ron all kinds of questions because Ron was one of his songwriting heroes, and Ron mentioned that he writes a lot of songs at the laundromat. Chris asked, ‘Don’t you have a washing machine at your house?’ Ron replied, ‘I don’t have a house. I rent an apartment; I can't afford a house.’ And Chris Martin looked like he was going to faint.”

More than 10 years later, Sexsmith still rents (a house now) and does his laundry at the laundromat. (Though he says this is partially because he likes to write songs there.) Overall, he describes himself as making an “OK living.” The financial reality of being a cult hero is that Sexsmith doesn’t make much money from album sales. Instead, he’s largely dependent on touring and especially publishing to make a living. Thankfully for Sexsmith, many artists — including Rod Stewart, Feist, Emmylou Harris, and k.d. Lang — have covered his songs. The most high-profile cover of one of his songs was the one that caught him the most off guard.

“One day I was having dinner when Michael Bublé called me out of the blue and said, ‘Hey, Ron, check this out!’” Bublé, the Canadian crooner who has sold more than 30 million records worldwide, played over the phone a Bossa Nova remake of Sexsmith’s “Whatever It Takes” that he’d just recorded with 16-time Grammy-winning producer David Foster. Sexsmith was shocked. “I’d been sending him songs for years — torchy, Sinatra kind of songs — and nothing. I never got any kind of feedback at all.”

Bublé wasn’t through with his surprises, though, and asked Sexsmith to come to Foster’s recording studio in Malibu, California, to add vocals to the track.

Sexsmith describes singing in front of Foster as “nerve-wracking,” but says that the legendary producer of Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” quickly put him at ease. “Bublé was there, too, listening and cheering me on.”

The Bublé/Sexsmith duet version of “Whatever It Takes” became the closing track on Bublé’s multiplatinum 2009 smash Crazy Love, which spent two weeks atop the Billboard 200 and won a Grammy for Best Traditional Jazz album. After 20 years in the music business one of Sexsmith’s songs (and vocal performances) was being heard by millions of people. It was a breakthrough for Sexsmith, but a largely anonymous one. Record buyers were buying an album with Bublé’s name on it, not his, after all.

Sexsmith didn’t get rich off the song, either. “I didn’t really see much money from that because I live off publishing advances and royalties, so whatever money came in, the publishing company used to pay themselves back first.”

Up until this point of his career Sexsmith had made a living as a perpetually “on the verge” artist, a fixture of “to watch” lists. But as he entered his forties it became increasingly difficult to get his music out into the world. No longer on a major label, Sexsmith was often forced to label shop each new album with varying results.

The Froom-produced Time Being, released in 2006 on Kiefer Sutherland’s newly formed independent label, Ironworks, was especially trying. “Kiefer was really nice, but at the time he was having a lot of alcohol problems, and that was sort of disastrous,” Sexsmith says. “Right away we had issues with the label because it was the only time I had a different album cover in the States than in the rest of the world. They didn’t want my picture on it.”

Sexsmith promoted the album with a tour that he describes as the worst of his life. “We were on this horrible, poor man’s tour bus, like an airport shuttle with no heat, and we were touring in January and February, freezing. I was getting sick. We tried to get out of our agreement with the tour bus company and they threatened physical violence."

The album, like two others he released around that time, “came out and sort of died the next day,” Sexsmith says. “So I felt my career was, I don’t know how true it was, going down the toilet.”

Sexsmith decided that if he was to reverse the downward trend he would need to shake things up for his next album. At a party Bublé made the unlikely suggestion of pairing Sexsmith with Bob Rock, the producer behind hugely popular, big-sound albums by Metallica, Bon Jovi, and Motley Crue. Sexsmith responded to this idea and reached out to Rock’s people to see if there was mutual interest. They quickly responded that Rock “loved Ron” and wanted to work with him, which was a huge relief to Sexsmith.

“It felt like it needed to happen,” Sexsmith says. “If Bob was to have said no I probably would have just sunk into this huge depression.”

The weight of this opportunity wasn’t lost on Sexsmith, who knew this very well could be his last and best chance to produce an album that made a mainstream impact.

“The night before my first session with Bob I went to this Elvis Costello taping of his show, Spectacle, and all of a sudden I told my wife, [musician Colleen Hixenbaugh, his partner since 2001] ‘I have to go. I don’t feel right.’ We went out the front steps and I just collapsed on the ground. I thought I was having a heart attack.”

Hixenbaugh told him he would have to cancel his flight, but Sexsmith, who now knows he was having a panic attack, insisted on going. Thankfully, Rock quickly settled him. “Right away I felt I was in good hands,” Sexsmith says. “He’s a very mellow guy, very nurturing.”

Long Player Late Bloomer paired Sexsmith’s typically strong songs with Rock’s polished studio sound, and resulted in some of the best sales of Sexsmith’s career. The response was especially strong in the U.K., where Long Player became the first of Sexsmith’s albums to chart (peaking at No. 48), and enabled him to book a headlining gig at the world famous Royal Albert Hall. The album didn’t bring Sexsmith anywhere near the Elton John-level of success he dreamed of as a boy, but it did represent a well-deserved high point in his career. Unfortunately, the high was short lived as Sexsmith’s follow-up, Forever Endeavour, didn’t sell nearly as well.

After a couple hours with Sexsmith an assistant engineer pokes his head into the room and announces that some new mixes are ready for his approval. Sexsmith inquires if we have everything we need, and when we say we do, he leads us past a Dolly Parton-themed pinball machine to the exit. There we chat a few more minutes, and as he proudly describes a two-decades-old family photo his daughter sent him that morning, it’s clear he’s in a good place in his personal life. He’s close to his children, happily married to Hixenbaugh, and even on amicable terms with his ex-wife, Jocelyn, whom he emails from time to time.

As far as finally achieving the mainstream recognition that has eluded him, Sexsmith is guarded but optimistic about his new album’s chances. “I’m a 50-year-old guy from Canada, so I can’t really have great expectations,” he says.

His new album, Carousel One, is named after the carousel at Los Angeles International Airport where Sexsmith, who has recorded his last few albums in Los Angeles, always ends up waiting for his bags. It features a “who’s who” of the city’s best sidemen, including bassist Bob Glaub (John Lennon, Rod Stewart) and keyboardist John Ginty (Santana, Dixie Chicks), and is a reaction of sorts to his last couple albums. Sexsmith says Carousel One eschews the “autotune and airbrushing” of Long Player Long Bloomer and “is a lot more of an upbeat, outgoing record than the last one I did, which was kind of downbeat.” Still, Sexsmith is quick to add that “it sounds like what I do, you know?” Indeed, the warm melodies that sporadically seep through the walls of the mixing room will feel familiar to fans of Sexsmith's work. Sexsmith, for his part, is happy with the results. “Everything comes at you in a direct way,” he says. “I’ve just really been loving the mixes.”

Mainstream hit or not, Sexsmith’s 20-year career could be viewed as an achievement in itself, a slow-burn trajectory that defied rock’s tendency to produce stars that flare up and burn out. His reputation for exquisitely crafted songs continues to feed a small but devoted fan base.

“He’s one of the greatest songwriters of the twentieth century,” his producer Jim Scott says once Sexsmith has gone off to listen to the mixes. “It’s a shame his music hasn’t reached more people.”