Around 10 p.m. on the night of Aug. 22, 2005, the Austin Police Department dispatched Officer Joel Davidson to an intersection a couple miles west of the Texas city’s downtown. A passerby had called to report that a woman in a pink shirt was sitting on the ground near the MoPac Expressway with her head in her hands, and no sign of a vehicle nearby. When the officer arrived, he found the woman on a swath of grass between an onramp and the freeway. She said her name was Heidi Cruz.

According to a police report recently obtained by BuzzFeed News, Officer Davidson proceeded to question Cruz, whose husband, Ted, was then serving as Texas solicitor general. He asked what she was doing by the expressway; she replied that she lived on nearby Hartford Street, and "had been walking around the area." She went on to tell Davidson that she was not on any medication and that she hadn't been drinking, aside from "two sips of a margarita an hour earlier with dinner." He wrote that he "did not detect any signs of intoxication."

The heavily redacted report goes on to describe that Davidson believed Cruz was a “danger to herself,” and notes that she was sitting 10 feet away from traffic. He asked if he could transport her somewhere — the proposed location is redacted — but she was "reluctant, stating that maybe she should ... get a ride home" instead. Eventually, Cruz followed him to his patrol car, and they departed the scene.

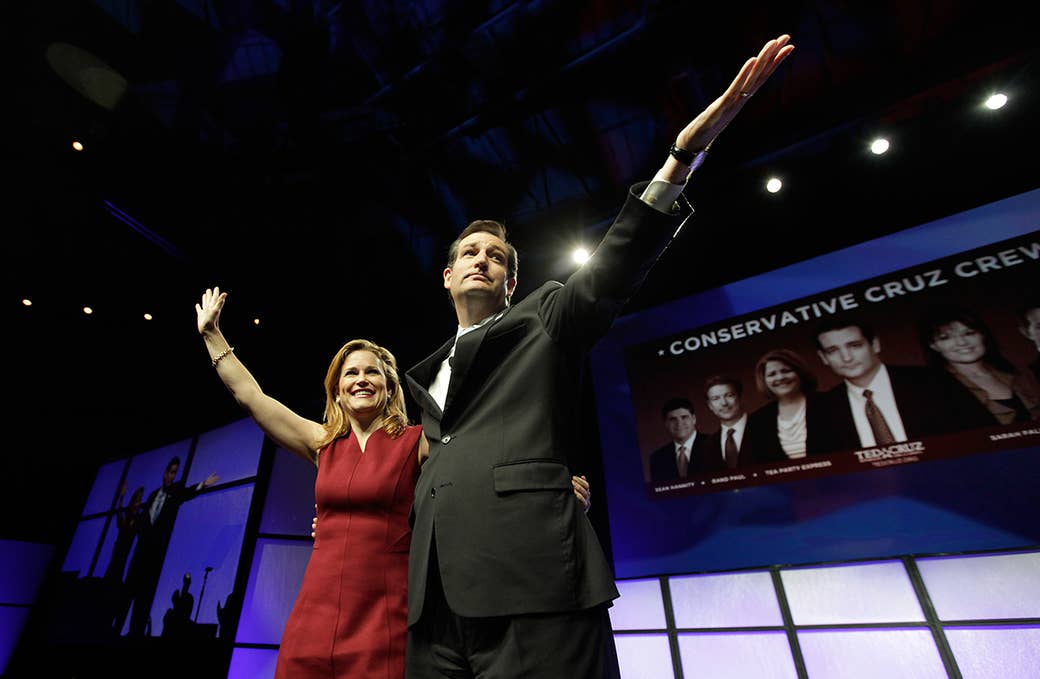

In response to questions about the incident, an adviser to Heidi Cruz's husband, Sen. Ted Cruz, sent a statement to BuzzFeed News shedding light on a period of their lives that the couple has not previously discussed in public.

"About a decade ago, when Mrs. Cruz returned from D.C. to Texas and faced a significant professional transition, she experienced a brief bout of depression," said Jason Miller, an adviser to the senator. "Like millions of Americans, she came through that struggle with prayer, Christian counseling, and the love and support of her husband and family."

BuzzFeed News requested an interview with Heidi Cruz to further discuss that night in 2005, and how she dealt with depression. A spokesman replied that she would consider the offer, and then two days later, reported back that she politely declined.

According to someone familiar with the situation, the Cruzes were aware of the police report — which was obtained by BuzzFeed News in response to a wide-ranging series of public-records requests — and they were resigned to the fact that it would eventually be made public, particularly as Ted Cruz moves toward a likely 2016 presidential bid. But while Heidi Cruz was not ashamed to talk about her experience, the person said, she ultimately decided against it because she didn't want to minimize the struggle of those who suffer from depression their entire lives by trumpeting her own happy ending.

The incident was a rare moment of visible vulnerability for a woman widely known to the public and among friends as an unflappable high achiever with preternatural poise. In a series of recent interviews with people close to the Cruzes and a review of her public appearances little mentioned in press accounts, the portrait that emerges is one that many career-oriented couples would recognize: two driven people, delicately negotiating the push and pull of their respective careers — and wrestling with the conflicts, compromises, and disappointments inherent to such a project. In 15 years of marriage, their parallel professional ascents have carried them from the bullpen of a national campaign to the upper echelons of Wall Street and Washington — and could soon have them contending for the White House.

For Cruz, the former Heidi Nelson, the trajectory was always expected to involve big things. She grew up in California with a religious family of Seventh-day Adventists, who stressed that personal success could be measured by good works. At just 4 years old, she began accompanying her parents on mission trips to Africa, where they provided free dental care to locals. When she was 12, she read a Time magazine article about the 1980 presidential election, and started to take an interest in government as a vehicle for public service, in its most literal sense. By the time she arrived at Claremont-McKenna College, a small liberal arts school outside of Los Angeles, she was plotting the intricacies of a career trajectory designed to one day land her a plum appointment in the federal government working in international affairs — an area where she felt she could make a difference in the world.

"She really knew where she wanted to go, and was all about getting there," said Ed Haley, a Claremont professor who became Cruz's mentor. They would meet often to discuss her career goals, and to talk through and tweak her various ladder-climbing strategies. "If you look over the past 50 or 75 years of the U.S. foreign policy establishment, most of those who are appointed into high positions are lawyers. Heidi and I discussed this a great deal," he said. "That's the mold." But she had little interest in being a lawyer; she wanted her private-sector training to be in business. So, they discussed which corporate skill sets might best position her for a job in a future administration, and she settled on finance.

Many who knew her believed she saw Wall Street as a pit stop. "She did definitely have a strong interest in government," said Jack Pitney, another Claremont professor, who helped get her an internship on Capitol Hill.

After a few years at J.P. Morgan in New York, she went to Harvard Business School and emerged, MBA in hand, with a bevy of lucrative job offers — including a highly coveted spot at Goldman Sachs.

Instead, she took an unpaid job on George W. Bush’s 2000 campaign.

Years later, she would explain her thinking at the time to a baffled-looking student interviewer during a taped Q&A at her alma mater. Cruz said she viewed the counterintuitive choice as a "measured risk," and recalled that her professors at Claremont had urged her to seize any opportunity she got to join a presidential campaign. "I didn't even have to touch base with them at the time ... for me, the decision was very clear," she said.

Haley, who closely watched his former protégé’s career, was thrilled to see her sticking to their plan. "That was very much the direction we had discussed," he said. "I had told her that, in general, political appointments come to those who find a way to do something constructive for politicians, and joining a campaign is one way to do that."

She turned down Goldman, packed her bags, and headed for Austin, where she took a position on the campaign's policy team, stashing her workout gear in a tiny cubicle, and spending long days tinkering with budget math and editing memos.

It was there that she met Ted Cruz, the ostentatiously brilliant, motor-mouthed Harvard Law grad who liked to talk about his debate championships, Supreme Court clerkship, and big plans for the future. Some in Bush headquarters were repelled by Ted's transparent ambition and steroid-infused self-confidence, but Heidi was drawn to him. She ended the campaign with a new husband, and an offer to work at the U.S. trade representative's office.

Those who encountered the couple were often struck by their almost palpable affection for each other — and the sharp contrast in their personal styles. Both Cruzes carry a kind of intensity about them, but whereas Ted's often manifested itself in passionate bursts of rhetoric that were not always properly calibrated to the setting, Heidi's was quieter, more polished and restrained. "It's hardly a revelation that Ted says off-the-wall things, whether it's with friends at dinner, or on the floor of the Senate. Heidi's not like that. She's not confrontational," said Haley, who added, "They're obviously deeply committed to one another." Another friend recalled, "He would light up every time he talked about her. It was always when he seemed the most human."

Several people also mentioned the earned intellectual respect they seemed to share for each other. "My sense was they had spirited conversations, in the best sense of the word, where they were both looking at each other to engage, and bounce ideas," one friend said. "I certainly don't think she's a yes man for her husband."

Her career took off. When Cruz moved to a job at the Department of the Treasury in 2002, she worked with the economist Brock Blomberg on the Latin America desk, shaping policy in response to the emerging market crises of the time. "I never thought of her as a true believer in the sense that she was very ideological," Blomberg recalled. Instead, she distinguished herself with a tenacious drive and a tireless work ethic. "The one thing I can say is she's a very earnest person. Whenever she had an opportunity, she gave it 100%."

Then, in 2003, Cruz was appointed director of Western Hemisphere on the National Security Council, reporting directly to Condoleezza Rice — exactly the kind of job she had been working toward since she carried textbooks across Claremont’s campus. Cruz was viewed by many inside the White House as a rising star, and it seemed likely that she would continue to rise if Bush were re-elected.

Things hadn't been going as well for the other Cruz in the Bush administration. After the campaign, Ted had landed with a thud at the Federal Trade Commission — a low-profile post far away from the action that offered little excitement for someone with his ambition. When he was offered the position of Texas solicitor general — a gig that would place him center stage in federal courtrooms, delivering forceful conservative arguments on behalf of the Lone Star State — it was a no-brainer. Ted moved back to Austin to begin making his name as a litigator, while Heidi stayed in Washington for her dream job at the White House. For more than a year, they maintained a long-distance marriage, flying back and forth on weekends and holidays.

One day in 2004, professor Haley, who had been spending some time at a Washington think tank, invited the Cruzes over for brunch. "Heidi said she was going back to Texas with Ted, and that he wanted to run for statewide office there, and it was too hard to maintain two homes," he recalled. Haley struggled to conceal his disappointment that his star pupil was walking away from the dream job they'd spent so much time planning for.

"Had she not been married, and free to choose, I think she would have stayed for three more years," he said. "My sense is she really loved what she was doing and chose to go back to Ted so that she could help him campaign ... She was sorry to go, and reconciled to going."

Upon returning to Texas, Cruz took a job as a vice president at Goldman Sachs in Houston. But after several years away from Wall Street, she felt out of practice and anxious about proving herself to her colleagues and subordinates — some of whom, she suspected, questioned her abilities, as she described at length in a panel discussion years later. She also quickly found that Houston's finance scene was considerably less accommodating to high-powered women than those of Washington or Manhattan.

"When I came out of Washington and the White House, I didn't feel that there was really a glass ceiling in the administration ... and Texas was very different," she would later say in a 2011 panel discussion. She was the only woman in Goldman’s Houston office, and described fumbling with hunting lingo during conversations with male clients. In the "very traditional culture" where she lived, few of the women in their social circles had careers.

And building financial models for the profit of a major investment bank wasn’t the same as trying to improve markets in poor Latin American countries. Asked years later whether she missed the public sector after leaving it in 2004, she responded, "I'm always quite honest in my answer so I have to say that I really do ... I think there is an important role to making a profit and doing so through a pretty definable skill set, and you can certainly impact industry. But to impact countries rather than companies, individually, is exciting and so I miss that component to it."

These were some of the frustrations weighing on Cruz during the “professional transition” in 2005 that would, according to the senator’s office, lead her late one August night to the grass by an expressway onramp. This period had been a sharp detour for a woman who had carefully plotted a career path she believed would enable her to serve the public and do good in the world.

Since 2005, however, the Cruzes’ lives have been marked by significant successes. Ted ended up taking longer to run for statewide office than planned — he formed and then abandoned a 2010 bid for attorney general — but in the meantime he was freed up to help his wife puncture Houston's finance boys clubs.

She began taking her husband — the accomplished attorney with Supreme Court war stories to spare — to dinners with male clients and colleagues. "He's very useful to me and interesting to clients, so it always helps me to bring in more business when I bring him along," she would tell an audience of Claremont's aspiring female financiers in 2011. She added, with a laugh, "I always kind of get him to help make the ask, and I always kind of go follow up. So, if you can marry somebody that is complementary to your business, it's great networking."

When Ted did eventually embark on a long-shot bid for the U.S. Senate in 2012, he suggested to Heidi, "Sweetheart, I'd like us to liquidate our entire net worth" — more than $1 million — "and put it into the campaign." The way he would tell it to the New York Times, his steadfast rock of a wife "astonished" him when she said without hesitating, "Absolutely." But in her version of the story, she reacted to her husband's proposal more like the savvy banker that she was. As she would recall to Politico, she proposed not investing any of their own money in the campaign "unless it made the difference between winning and losing." Really, she wanted to test the viability of his campaign by seeing if he could drum up funds from other donors. As she put it, it was "just common investment sense."

November 2012 was a big month for the Cruzes: Nine days after Ted won his insurgent Senate race, Goldman Sachs announced that Heidi would be promoted to managing director. And though she continued to miss the public sector, her success at Goldman enabled her to get the firm involved in various philanthropic projects, temporarily satisfying her appetite for service, she has said.

Of course, in the coming weeks, the Cruzes are likely to embark on a mission that, if successful, would make them the most famous public-sector figures in the world. Heidi Cruz has already proved helpful in filling her husband's campaign war chest as he marches off to the presidential fray. Last December, Republican Rep. Kevin Brady, who has deep ties to major political donors in Houston and Dallas, said her status at Goldman and connections in the finance world make her "a wonderful, not-so-secret weapon" for Ted's fundraising efforts. "She's well-respected and has lots of admirers," Brady told the National Journal. "So that could be part of the reaching out — whether it's Wall Street or Texas."

But many who know her wonder how Cruz will respond to the expectations placed on political wives, particularly in the conservative activist circles where her husband is most popular.

Over the course of her husband's rise, she has proudly defied the cookie-cutter molds sometimes forced on candidates' wives, speaking out against "people who believe that women who work outside the home are uncaring and can't be good mother," calling them "just misguided," and adding, "I would work and want to have a career, regardless of if my husband works. It's not only for the money."

When she sat on a 2011 panel at Claremont — titled "Women in Finance: Can You Achieve Work/Life Satisfaction?" — she urged the women in attendance to pursue careers in finance, preaching that they often make better investment bankers than men. She advised, too, that live-in help can be critical for working couples. The Cruzes have two daughters, the elder born in 2008, and live in a downtown Houston high-rise. "I still don't understand my friends who say it's not worth it to them to have someone living with them," she said. "It is worth it to me on every level. I don't mind sharing a bedroom down the hall if someone is willing to do all that. But I'm very comfortable with that and it allows me to work 80 hours a week and be... part of my husband's career, as well.”

But while such full-throated defenses of professional women have been commonplace in Heidi Cruz’s past, comments like those could prove combustible in a Republican primary.

"It's sort of interesting to think of her now as a potential first lady sort of person because that's not how I saw her back then," said Blomberg, who worked with Cruz at Treasury. "I just didn't see her as making her career about her husband ... I see her as being a lot deeper than that."

As for professor Haley, he has continued to track his protégé's career over the years, and holds out hope that she will one day return to an administration job, perhaps after their daughters are grown up. "She really does have the ethic of public service," he said. In the meantime, he said he was in awe of how she has managed to accomplish so much.

"It can't be easy to juggle all these balls: family, work, and Ted's ambitions," he said. "Her life is a complicated one. But that's Heidi. She can handle that."

Andrew Kaczynski contributed reporting to this story.

Correction (8:04 p.m., March 18): When a police officer approached Cruz in 2005, he wrote that he believed she was a "danger to herself." A previous version of this story misquoted the report, which is linked above.