The conservative book business has seen better days. Ten years ago, the genre was a major source of intellectual energy on the right, and the site of a publishing boom, with conservative imprints popping up at industry giants like Random House and Penguin. But after a decade of disruption, uneven sales, and fierce competition, many leading figures in the conservative literati fear the market has devolved into an echo of cable news, where an overcrowded field of preachers feverishly contends for the attention of the same choir.

"I think the problems in the conservative publishing arena are more acute than in the rest of the industry," said Keith Urbahn, former chief of staff to Donald Rumsfeld, who now runs a communications firm in Washington and works as a literary agent for conservative authors.

The challenges afflicting the market are varied, but in interviews with BuzzFeed, several editors, agents, and executives faulted the same trend they were celebrating in 2003, when mainstream publishers began elevating conservative editors, like Adam Bellow and Adrian Zackheim, and luring high-profile Republican figures like consultant Mary Matalin into the book business. At the time, many on the right welcomed this development as the sort of victory that had eluded them in Hollywood, academia, and the mainstream press — a mass influx of conservatives that would wrest the industry from the hands of liberal elites, and work to reverse the tide of the culture wars.

Instead, what followed was the genrefication of conservative literature. Over the next 10 years, corporate publishers launched a half-dozen imprints devoted entirely to producing, promoting, and selling books by right-leaning authors — a model that consigned their work to a niche, same as science fiction or nutritional self-help guides. Many of the same conservatives who cheered this strategy at the start now complain that it has isolated their movement's writers from the mainstream marketplace of ideas, wreaked havoc on the economics of the industry, and diminished the overall quality of the work.

Editors at these imprints face unprecedented pressure to land cable news and radio provocateurs like Ann Coulter, rather than promote the combative intellectuals, like Allan Bloom and Charles Murray, on whom the business was first built.

"You are left to rely completely on cable and radio [for promotion] and as a consequence of that, you have to provide those venues the type of material they want," said Bellow, who runs Harper Collins' conservative imprint, Broadside. "It's become a kind of blood sport and the most ruthless gladiator comes out on top."

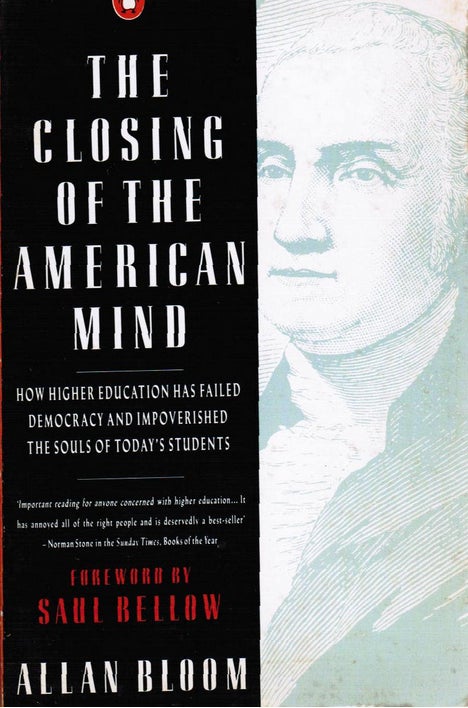

The gutting of the conservative book market could mark the end of a cycle that began in the summer of 1987, when a roomful of bemused Manhattan publishing types gathered at the offices of Simon & Schuster to toast Bloom, a University of Chicago philosopher whose new book, The Closing of the American Mind, condemned the American higher education system for having "impoverished the souls" of its students. The volume had become a surprise mega-hit, eventually selling more than a million copies by channeling a popular sentiment on the American right that few in the literary class could relate to.

Roger Kimball, a conservative critic present at the party, recalled meeting Simon & Schuster publisher Joni Evans. Kimball said Evans was "pleased as punch" to have a runaway bestseller on her hands, but seemed perplexed by the book's success. "It was clear she had never opened the book," he said. "She had no idea what was in it."

Still, the book had alerted the New York publishing industry to a potentially lucrative fact: Conservatives knew how to read.

One of the first editors to figure this out was Bellow, who has been present at every stage of the conservative publishing evolution over the past two-and-a-half decades. The son of the late novelist Saul Bellow, he spent much of his career as a rare conservative editor in mainstream publishing — first at Free Press and then Doubleday — building a list that included general-interest books alongside provocative right-wing works like Charles Murray and Richard J. Herrnstein's The Bell Curve, and Dinesh D'Souza's Illiberal Education. In the '90s, when the independent partisan publisher Regnery was dominating best-seller lists with anti-Clinton polemics, Bellow was one of the few mainstream editors to take advantage of the phenomenon, commissioning a young, right-wing reporter named David Brock to write 1996's The Seduction of Hillary Rodham. (Brock would undergo a political epiphany shortly thereafter and reinvent himself as a Democratic operative.) Bellow continued to usher conservative books onto the best-seller list from his post at Doubleday in the 2000s — including Jonah Goldberg's Liberal Fascism — before eventually being wooed to Broadside in 2010.

Bellow said he's proud of the work his imprint has done, but he's conflicted about the current conservative publishing landscape.

"I was happy to publish conservative books as part of a mix of general books," he said of his earlier career. "There's a tension for conservatives. They didn't want to be ghettoized. The whole point was that they wanted to bring their ideas to a mass audience. The irony was that just as they achieved respectability for their views and were accepted into mainstream publishing, they were hived off into imprints."

That of course isn't the only problem afflicting the conservative publishing market. Borders bookstores, whose widespread placement in exurban malls and rural communities made them magnets for right-leaning customers, shut down in 2011. And the web has decimated the subscription-based "book clubs" that launched a slew of conservative best-sellers in the '90s and early 2000s.

Meanwhile, the proliferation of conservative publishers has made the economics of their genre much tougher, with an ever-increasing number of books competing for an audience that hasn't grown much since the '90s. One agent compared conservative literature to Young Adult fiction, an unsexy niche genre that quietly pulled in respectable profits for years until the big houses took notice, and began entering into bidding wars for promising authors, and flooding the market in a frenzied attempt to find the next Twilight.

While best-sellers by famous pundits like Bill O'Reilly's Killing Jesus, and Charles Krauthammer's Things That Matter continue to give conservative publishing a veneer of wild success, publishers say the ruthless competition on the right has made it increasingly difficult to turn a profit on midlist books.

This dynamic may be best illustrated by the quadrennial scramble in publishing to sign prospective presidential candidates, who are bound by tradition to write an autobiographical manifesto ahead of the election. The casual Barnes & Noble browser is unlikely to have ever purchased one of these books — almost nobody does — but he will recognize the subgenre by its uniform covers: the patriotic color scheme, the besuited politician striking a square-shouldered pose, the author's name and title stamped across the dust jacket in imposing, all-caps lettering. Inside, the books follow a well-worn formula, lacing lofty talking points and vaguely drawn policy proposals with a sanitized personal narrative that reads as though it has been vetted by a thousand political operatives and stripped down to a fourth-grade reading level.

"No self-respecting seeker of high office can enter the fray without a book that bears his name on the title page," said Kimball, who now runs Encounter, a small nonprofit imprint for smart conservative books. "You know, next to catalogues for exhibitions, they're probably the least read sort of books being published. They're sort of a union card for candidates, I suppose."

These books have been a ritual in American politics for decades, and in the past, experts said, publishers were relatively clear-eyed about signing such authors; they paid reasonable advances, held their noses as they signed off on the sterilized prose, and then crossed their fingers in hopes that that their guy would become president — an outcome that would ensure massive book sales for years to come. If their author didn't make it to the White House, they could usually count on relatively minor losses, or even breaking even. It was always a risk, but a calculated one.

But today, as numerous conservative imprints, Christian publishers, and mainstream houses compete to sign a finite number of aspiring Republican presidents, publishers are being forced to pay much larger advances than they're used to.

For example, Tim Pawlenty, a short-lived presidential candidate in 2012, received an advance of around $340,000 for his 2010 book Courage to Stand. But the book went on to sell only 11,689 copies, according to Nielsen Bookscan, which tracks most, but not all, bookstore sales. What's more, Pawlenty's political action committee bought at least 5,000 of those copies itself in a failed attempt to get it on the New York Times best-seller list, according to one person with knowledge of the strategy.

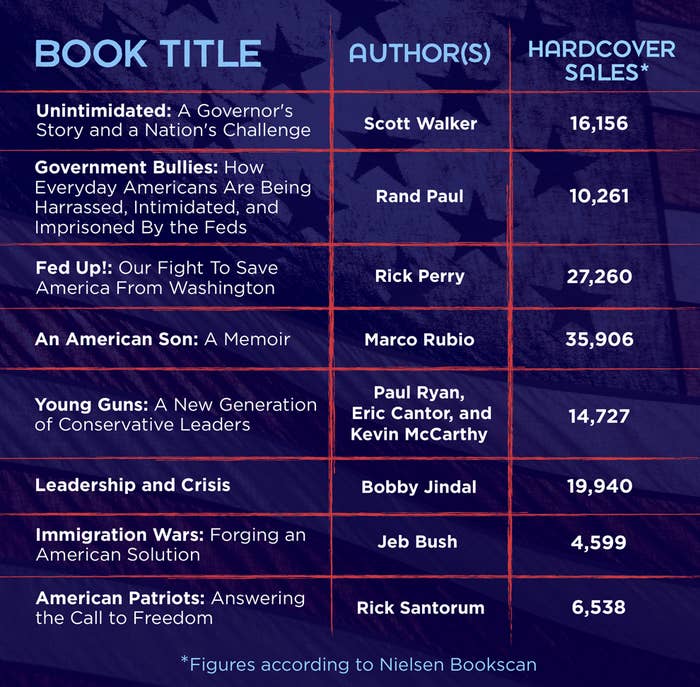

This pattern continues as you scan the works of recent and prospective Republican presidential candidates. According to one knowledgeable source, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker received an even larger advance than Pawlenty's, and Bookscan has his 2013 book Unintimidated selling around 16,000 copies. Sen. Rand Paul's latest, Government Bullies, has barely cracked 10,000 sold; and despite spending months in the 2012 GOP primaries, Rick Santorum's book about the founding fathers, American Patriots, sold just 6,538 copies. Perhaps most surprising, Immigration Wars, co-authored by Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor who consistently polls in the top tier of the Republican 2016 field, sold just 4,599 copies.

Meanwhile, Marco Rubio's 2012 autobiography, American Son, has sold around 36,000 copies — a figure one conservative agent described as "respectable," before pointing out that Rubio received an astounding $800,000 advance, according to a financial disclosure. The publisher's bet, he speculated, was that Rubio was going to be selected as Mitt Romney's running mate. He wasn't.

"The publishing business is more like a casino than a real business," Bellow said. "We're gambling… and editors are inveterate optimists. That's just part of the job description."