What just happened?

The rate for subsidized Stafford Loans, a federal loan program for low-income undergraduate students is going to double from 3.4% to 6.8%. The law that sets the rate at 3.4% expired, and there was no replacement passed before the July 1 deadline. And since Congress is not in session because of its July 4 recess, any agreement to restore the rate or adjust it would either leave out borrowers who get loans starting today or would have to be retroactive.

What’s the subsidy?

The subsidy comes in two parts. One is the interest rate of 3.4%, and the second is that the government pays the interest that accrued while the student is enrolled as an undergraduate. There's also a six-month grace period after graduation before the borrower has to start paying back the loan. This means that the amount a student has to repay only starts growing beyond the principal six months after he or she graduates. Over one's entire time in college, the cap on subsidized student loans is $23,000.

Who's paying 3.4%?

Only those students who got loans between July 1, 2012, and June 30, 2013. In 2007, the interest rate for subsidized loans was fixed at 6.8% with the goal of bringing it down in steps to 3.4% for 2011. That bill was set to expire in 2012, but a last-second compromise extended the subsidized rate for a year. The expiration of the 3.4% rate would not raise anyone's interest rates; it would instead make new subsidized loans more expensive. It's estimated that about 7 million students will take out subsidized loans. For the 2007–2008 fiscal year, the Congressional Research Service estimated that 40% of subsidized borrowers came from families with incomes under $40,000.

How big is the Stafford program?

There are a few different federal student loan programs, of which Stafford, subsidized and unsubsidized, is only one part. There are also the PLUS and Perkins programs, which cost about $20 billion per year. Unsubsidized loans cost about $59 billion and subsidized are $28 billion per year. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that maintaining the lower subsidized rate would cost $41 billion over the next 10 years.

What’s the difference between paying 6.8% and 3.4%?

According to the Congressional Research Service, if you borrow $5,500, the largest single loan amount allowed for juniors or higher in college, once you start having to repay your loan after the six-month grace period, you owe $5,594. Your total principal and interest payments for the loan at the subsidized rate are $6,606. At the unsubsidized rate, 6.8%, you accrue $187 during the six-month grace period, and start paying back a balance of $5,678 and have a total principal and interest to pay back of $7,854, a difference of $1,248. Assuming the loan is paid off over 10 years, the minimum monthly payment for that $5,500 subsidized loan at 3.4% is $55 and at 6.8% is $65.

What's next?

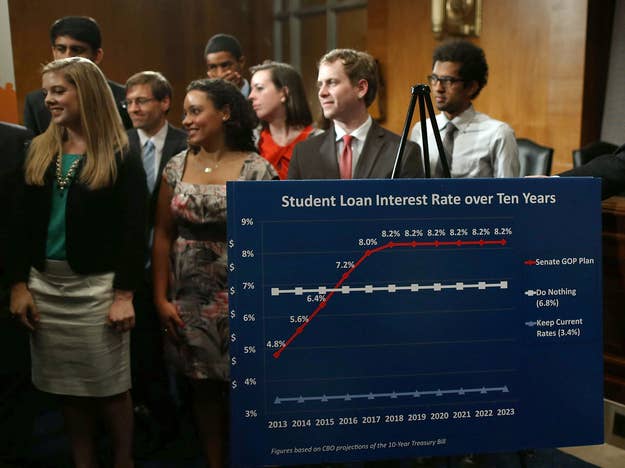

That's very unclear. The GOP-lead House passed a bill in May that would allow interest rate on government loans to float based on the government's cost of borrowing, but the White House opposed the bill. Tom Harkin, a Democrat from Iowa and the head of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, favors extending the subsidized rate for another year and retroactively adjusting the rates to the lower level of any loans taken out after the current rates expire. A bipartisan group of senators, led by Joe Manchin, a moderate Democrat from West Virginia, came out with a plan last week that would set the interest rate of new loans at the federal government's 10-year borrowing rate plus 1.85% for undergraduate Stafford Loans.

All the existing plans agree on maintaining the other features of the subsidized program — the no interest for four years and the grace period — there is just disagreement over the rate. "They all do the same thing in slightly different ways, there is room to compromise, there aren't big ideological differences," says Matthew Chingos, a fellow at the Brookings Institution. If Congress and the president agree, however, to maintain the 3.4% rate, there might still be time to fix it retroactively because very few loans are actually signed in July, says Chingos, and promissory notes for loans in the upcoming year tend to be signed in August.