The media industry has been in a state of never-ending consolidation for decades, with conglomerates being swallowed by conglomerates, and others being chopped up and resold in a vast game of corporate Lego. As a result, the giants that now dominate the business are often incredibly complex: Take a look at the corporate maneuverings of John Malone's Liberty Media empire, or the leviathan that is Comcast.

In late October, bankers at UBS tried to throw a couple more ingredients into the sausage grinder. In a pitch to film and TV giant Sony Entertainment, they proposed taking over AMC Networks, the owner of cable channels including AMC, Sundance, and IFC.

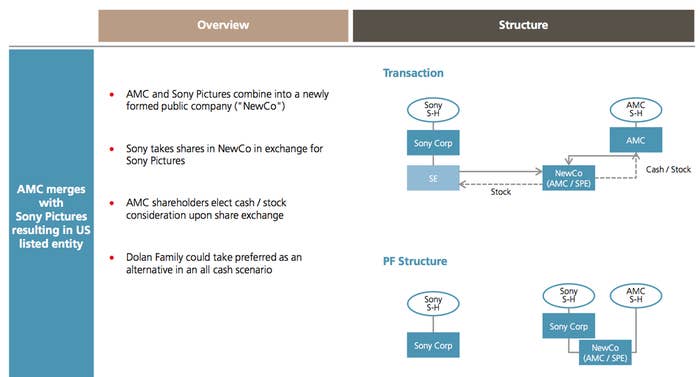

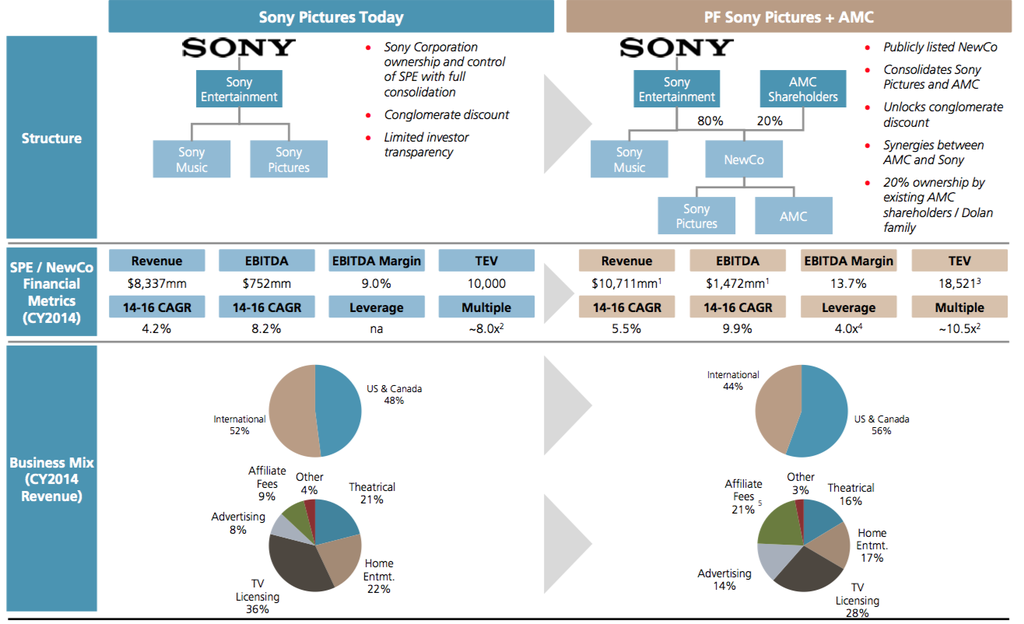

But this is media, so the deal couldn't be that simple. Sony shouldn't outright buy AMC, the bankers said in a presentation leaked alongside millions of others in a hacking attack late last year. Instead, the bankers said, Sony Pictures should be spun off from its Japanese parent company, into a new company, which would then be merged with AMC. Existing Sony shareholders would own 80% of the new business, and AMC would own 20%.

The convoluted exercise — never followed up on by Sony — is an example of how the complicated and sometimes baffling structure of the media industry leads to deals that are designed to satisfy needs beyond simple economic rationalism.

It's also an example of the media consolidation arms race currently under way, as huge players look to get even bigger to remain in a similar weight class as Comcast, which is already the country's largest cable company, and has agreed to buy Time Warner Cable, just a few years after swallowing up NBC/Universal. Telecom giant AT&T, has agreed to buy DirectTV, one of the nation's biggest pay TV operators.

"Scale [is] becoming increasingly critical with recent wave of cable consolidation (Comcast / TWC / Charter, AT&T / DTV) and large scale content M&A expected to shortly follow," the presentation says.

A Sony spokesperson declined to comment; AMC and UBS did not respond to requests for comment.

The presentation, which was included in a trove of Sony Entertainment CEO Michael Lynton's emails leaked by hackers last year, was prepared by UBS investment bankers. The rationale for the complex deal was Sony Pictures was "missing valuable U.S. cable network portfolio" that would turn Sony into a "leading television business with content production and distribution across all platforms and geographies."

The proposal envisioned Sony purchasing AMC at a 30% premium to its then-price of $58.44 (the stock is now at $63), a $8.48 billion deal including AMC's $2.8 billion in debt. A person close to Sony said that the presentation wasn't solicited by Sony executives and wasn't considered by Lynton, although such proposals are often prepared by investment bankers and presented to companies they have relationships with.

AMC Networks, which broadcasted the Sony-produced Breaking Bad on its flagship channel, has a "proven original programming model, secure distribution, valuable brand for advertisers and strong international channels," the pitch said, and would, importantly, provide "significant cash flow generation for Sony."

Many analysts consider companies with a library of high-quality original serialized content ready for broadcast — like Time Warner's HBO and AMC Networks' AMC — as increasingly valuable thanks to the ability to distribute shows like Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead, and Game of Thrones more widely to devoted fans throughout the world.

Richard Greenfield, an analyst at BTIG, said he didn't think AMC was a good buy, and wouldn't be purchased by anyone in 2015 because two of its three must-watch shows, Breaking Bad and Mad Men, have ended or will end. On top of that, TV advertising is still under pressure, the cable TV "bundle" is being gradually picked apart, with only truly must-see "appointment" TV holding up pay TV's expensive pricing. And if cable bundles shrink in size — like Dish Network's new streaming Sling TV service — AMC could be left on the outside (it's not included on Sling TV).

But with a cable network, Sony would also have a natural destination for the shows it produces, international distribution through Chellomedia, the overseas cable business AMC acquired from Liberty Media in 2013, and would get access to steady revenue from AMC's payments from cable providers.

AMC has long been rumored to be an acquisition target, and its recent success with Don Draper and Walter White added to the sheen. Investors and analysts have also long pushed some kind of reorganization of Sony and making its entertainment and movie assets somewhat independent from the company.

Activist investor Dan Loeb advocated for listing a 20% stake of Sony's entertainment business so that it could get its own stand-alone from investors. Sony executives have long said they don't have any interest in splitting up the company. Sony CEO Kazuo Hirai told Variety last year, "I'm not entertaining even the notion of selling our entertainment assets."

Like many deals dreamed up by finance types, the numbers behind the proposed tie-up are more complicated than just adding up all the cash the businesses generate on their own. UBS projected that the deal would generate $3 billion in value from the combined companies, just by taking a piece out of Sony — the assumption being that investors would pay more for a pure-play entertainment company than they would for one locked up inside a sprawling consumer electronics business. The bankers also projected some $100 million in "synergies" — essentially, money saved by getting rid of work that is duplicated — between the two.

UBS estimated Sony's television and movie business had revenues of $8.4 billion, earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization of $752 million, and a multiple — meaning the ratio between a company's per share earnings and its overall value and a measure of investor's estimate of growth of future revenues — of 8X. The new company with AMC would have revenues of $10.7 billion, EBITDA of $1.47 billion and a new multiple of 10.5X.

Sony Pictures, the bankers estimate, is worth $10 billion, and the two companies together would have an enterprise value of $18.5 billion. The value of AMC's stock when the presentation was given, however, was $5.6 billion. AMC today has a market capitalization of $4.45 billion.

An additional complication in the proposed deal was how to treat the Dolan family, which controls two-thirds of the shareholder votes at AMC through their ownership of the company's class-B shares, which carry extra voting power.

An all-cash acquisition of AMC, the bankers said, would mean a hefty tax bill for the Dolans. If, however, Sony Pictures and AMC were combined into a new company, the Dolans would own 3.4% of its stock and pay less in taxes than if they received cash or Sony stock.

Odd structures to reduce taxes are common in this kind of dealmaking. In March, Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway announced a deal to exchange 1.6 million shares of Graham Holdings for cash, Berkshire shares, and a TV station. The deal structure helped the companies avoid nearly all taxes.

And the diverse holdings of media tycoon John Malone, the Michael Jordan of media dealmaking, contain many complex corporate structures that have helped avoid hundreds of millions in taxes.

The leaked emails show that Sony executives, including Lynton and Sony Television chief Steve Mosko, have relationships with AMC CEO Josh Sapan and have discussed deals with the companies in the past. In June, Mosko emailed Sapan to inquire about a deal to acquire some Chellomedia assets, "Are you considering spinning off pieces of chello? If so …we may be interested," Mosko wrote. Sapan responded, "We're currently holding on to all of it" but added "If you ever identify opportunities for us to pursue together that are new, we would like to examine."

The emails also indicate that UBS banker Sam Powers, who is the co-head of the bank's technology, media, and telecommunications practice, met with Lynton in the middle of October. The presentation came back to Lynton on Oct. 30.

On the night of the Emmys, Lynton emailed Sapan congratulating him on the network's wins, including Breaking Bad's five trophies, and asked if he could get a copy of Boyhood, the Richard Linklater film produced by AMC-owned IFC.

"If we could get a copy I would, for just a day, be a star around my house," Lynton wrote. "See you soon I hope."