On 27 January 2017, it will be the 72nd anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland. It will also be the UK's Holocaust Memorial Day, created in 2001. The worldwide Jewish community will mark Yom HaShoah Holocaust Remembrance Day in May.

This is how the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust describes the Holocaust:

Between 1941 and 1945, the Nazis attempted to annihilate all of Europe’s Jews. This systematic and planned attempt to murder European Jewry is known as the Holocaust (The Shoah in Hebrew).

From the time they assumed power in 1933, the Nazis used propaganda, persecution, and legislation to deny human and civil rights to Jews. They used centuries of antisemitism as their foundation. By the end of the Holocaust, six million Jewish men, women and children had perished in ghettos, mass-shootings, in concentration camps and extermination camps.

Victims of the Holocaust also included gypsies, the physically and mentally disabled, homosexuals, political opponents, trade unionists, and prisoners of war, among others.

Some survivors have dedicated themselves to educating others about the atrocities by speaking at schools and public events around the world. With the help of the Holocaust Education Trust, we met four of them in their London homes: Lily, Josef, Renee, and Zigi, originally from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary.

Lily Ebert has revisited Auschwitz seven times, first in the early 1980s and later with two generations of her family: her daughter and granddaughter. The 85-year-old is keen for me to visit, saying on the phone, “This is the last minute, the very last minute, for us to tell our story.”

Lily has over 1,000 letters in her home from schoolchildren who have been moved by her speeches. “Why am I telling you this story now? Or to anybody?” she asks me in her dining room. “Not that you should know how much I suffered. It’s not your problem, you have your life. Everybody has his or her life.

"I want to show the world what can happen when people are not tolerant of each other. I want to teach tolerance.”

Lily Ebert, Holocaust survivor

Lily rejects a traditional style of interview, preferring to tell her story her way. “The truth is, I know what I want to say," she tells me. "I don’t need questions.”

She has had three very different lives, she says: “I had my protected childhood, I had the life in the hell, and I had the life after the hell, to begin a new life.” The eldest of six siblings, Lily grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Bonyhád, Hungary, and was sheltered by “the best parents that anybody could ask for” from persecution during the early years of the war.

Her childhood was cut short in 1944 at the age of 15 when Germany invaded Hungary, by which time, she says, “75% of the Jewish population was not alive any more. ... I don’t know how, but even the grown-ups didn’t know that – the communication was not like today."

The invasion came at a time when victory for Germany looked unlikely. “They knew they did not have a lot of time, but they wanted to destroy the Hungarian-Jewish population. They already knew how to do it."

Jewish people were forced to to give up all property and to wear Star of Davids on their clothing to single them out. Lily's family were moved to a Nazi-assigned Jewish ghetto, then, at the beginning of July 1944, were taken to a railway line where cattle trucks were waiting. Seventy to eighty people were forced into each carriage and shared two buckets, one containing water, the other for human waste.

“I cannot describe the heat," Lily says. "I promise you, today if they sent animals to slaughter that way, the whole world would cry out. Quite a few lucky people died on the way.”

Lily's mother was concealing jewellery inside the heel of one of her shoes, which had been nailed in place by her brother. During their journey, her mother swapped shoes with Lily, as they had the same size feet. "Why she did it?" asks Lily, "I really don’t know."

After travelling for five days, the train arrived at its destination: Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Ordered off the train, Lily and her family were lined up in rows. A German soldier "with shiny boots and a stick in his hand" sent people either to the left or the right with one movement of his hand. "Old people, mothers with babies, were sent to the left. Young people who they saw could still work, they were sent to the right."

The soldier making the selection was the notorious Dr Josef Mengele, a Nazi in Auschwitz who performed medical experiments on prisoners and is known to have carried out many atrocities.

Lily's mother, younger brother, and sister were sent to the left, while Lily and two of her sisters went to the right. Those on the left were taken straight to the gas chambers. "Mothers with babies, young boys and girls, walked to their deaths. But they didn’t know it."

Lily and her two sisters soon came to realise the reality at Auschwitz: "We saw nearby a chimney. From the chimney fire came out, and this terrible smell.

"We asked people who were already there, what sort of factory is it? They told us, 'That is not a factory, they are burning your relatives.' ... And you know what we told them? ‘You are mad.’ We wouldn’t believe that. But very quick, we found out that this was true."

Listen to Lily's account of arriving at Auschwitz:

At Auschwitz, Lily and her two sisters endured brutal roll calls outside their huts where strict registers were taken and the dead were taken away. They also faced frequent "selections", at which stronger prisoners would be chosen for factory work and those who had become weak or ill would be taken to the crematorium.

In October 1944, she was chosen to work in an ammunition factory with her sisters in Altenbourg, Germany. They worked 12 hours a day with little food. "It was somehow easier because it was not a crematorium, it was not the selections," she says.

Then one day in April 1945, the Americans bombarded Leipzig in Germany. Lily could hear it from Altenbourg. "[The German Nazis] took us on a death march," she says. "They wanted to take the people from the factory to a wood and finish us, kill us. We walked a few days without food, we were not sleeping. The worse thing was that this time we had no shoes."

After three days, American aeroplanes appeared overhead and the German soldiers ran away. Lily was liberated.

"To the American soldiers, we didn’t look like men or women, we were in rags, half-dead. I think they hadn’t seen anything like that in their lives. But they saw one thing: They had to help us."

Throughout her time at Auschwitz and Altenbourg, Lily kept the gold pendant; first in her shoe, and then in a piece of bread when the heel wore out. "And this little pendant," she says, pointing to her neck, "I wear every day."

She shows me a little hole in the pendant, explaining proudly that it was where her brother nailed it to her mother's shoe. "I think this is the only gold that went in to Auschwitz and came out with the original owner," she says.

What does Lily think she owes her survival to? "If somebody tells you that he or she survived because they were clever, it is not true. It was chance.

"Maybe I had to survive, because I promised myself in the camp that if by some miracle I survived, I would tell the world what happened. I could see that the world didn’t know."

Lily has kept her promise, and has spoken across the globe at schools of many faiths, including Jewish, Christian and Muslim.

"[If] your skin is white or black, you belong to another religion, or another nationality, it makes no difference," she says, ending her story. "You are no better or worse than me, you are only different. … For all of us humans our blood is red, and when you cut us, it hurts."

Josef Perl, Holocaust survivor

Josef Perl was forced to fend for himself at a young age for most of the war. He paints a picture of an idyllic early childhood in the rural town of Veliky Bochkov, then part of Czechoslovakia. The only boy in a Jewish family, Josef had eight sisters and was particularly close to his father, who ran a sawmill. "I had a happy life, lovely sisters, lovely parents," he tells me. "We treasured one another." Josef remembers his local Jewish neighbours visiting his house for High Holidays and reading from their own Torah Scroll.

The animals owned by Josef's family made a huge impression on him, including a horse given to him when he was four and a dog that always followed him for protection.

On his way to school, Josef would sit on his horse and the dog would take the horse's reign in his mouth and lead them safely on the journey. The three were inseparable. "[They] were one with me, we understood one another," Josef says.

When Josef was 11, in 1938, German and Hungarian soldiers came to the family's area and took all the animals from the local Jews, including Josef's horse. When one of the soldiers grabbed Josef, his dog growled. The soldier shot the dog. "I lost my horse and my dog in one day," he says.

Anti-Semitism came to Josef's school as Hungarian teachers replaced Czech teachers. On his first day back at school after a brief closure, the new teacher immediately announced to the class: "The Jews sit on this side, and the Christians on that side."

"It came over to the children so strongly," Josef says, "that when the time came ... to go and play ... we thought that when we go out to the playground we would mix as we had always mixed together – boys and girls.

"The first thing the children said was, ‘No, no, no, you’re Jews, you go over there, don’t come with us.’"

No longer riding his horse to and from school, Josef walked the journey. One day he was approached by soldiers that lined the main road near his house. They cut off the ringlets of hair that reached down to his shoulder. "Ringlets are like two arms to a Jewish boy," Josef says, "I went home and cried because I felt I had lost both my arms." Josef chose not to return to school.

Eventually the Jewish families living within a mile of the main road were rounded up and placed in a large tent, with water arriving in a lorry three days later. Josef and some other boys dug under the edge of the tent and sneaked out to steal food for their families: potatoes, beans, corn on the cob. On one trip out, the boys returned to hear shots coming from the tent. Watching from a distance, they saw soldiers take their families away in a lorry. "We went back to the tent to see what had happened and saw all the carnage, all the dead bodies left for the animals to devour." The old people and babies of the group had been shot.

Josef and the boys went into the forest, hiding for about three weeks. Realising they could not stay there much longer, they decided to split up. "We said our prayers every morning and every evening. One boy went, then another boy went, until I was left on my own.

"I started to cry and I called out, I said, ‘God, I’m alone. Look after me.’"

He headed to the town in search of food, where he saw soldiers and horses. He offered to groom one of the soldier's horses, and was handed a brush. "I brushed the horse, and [I groomed it] like a mirror, lovely. ... I said, ‘Thank you very much for letting me do this for you.’ He caught hold of my arm and said, ‘Don’t go away.’"

The soldier fetched a bowl of soup in repayment, and Josef realised they were the soldiers that had shot his neighbours. He left the soup uneaten on a chair and walked away.

Later, Josef fell in with a gang of boys on the street and stayed with them for a month, stealing to stay alive. Fearing the boys would discover his Jewish background, he left and went in search of his parents and sisters.

For two years he moved from one Jewish ghetto to another. In one, he was rounded up with the other inhabitants and taken to a field to be killed. As he waited to be shot, he saw his mother and four of his eight sisters. Before he could cry out, they were shot. As it was coming to Josef's turn – he was "around seven rows away" from his turn to be shot – an air-raid siren rang out, and the crowd scattered. Josef had escaped again.

After a period of freedom, Josef found himself back in another ghetto. For the rest of the war, he was moved between concentration camps – Auschwitz, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, Gross-Rosen, Balkenhain, Hirschberg, Buchenwald – finding ways to survive by proving himself to be a resourceful worker.

Listen to Josef describing an encounter with Voltag, a murderous concentration camp inhabitant:

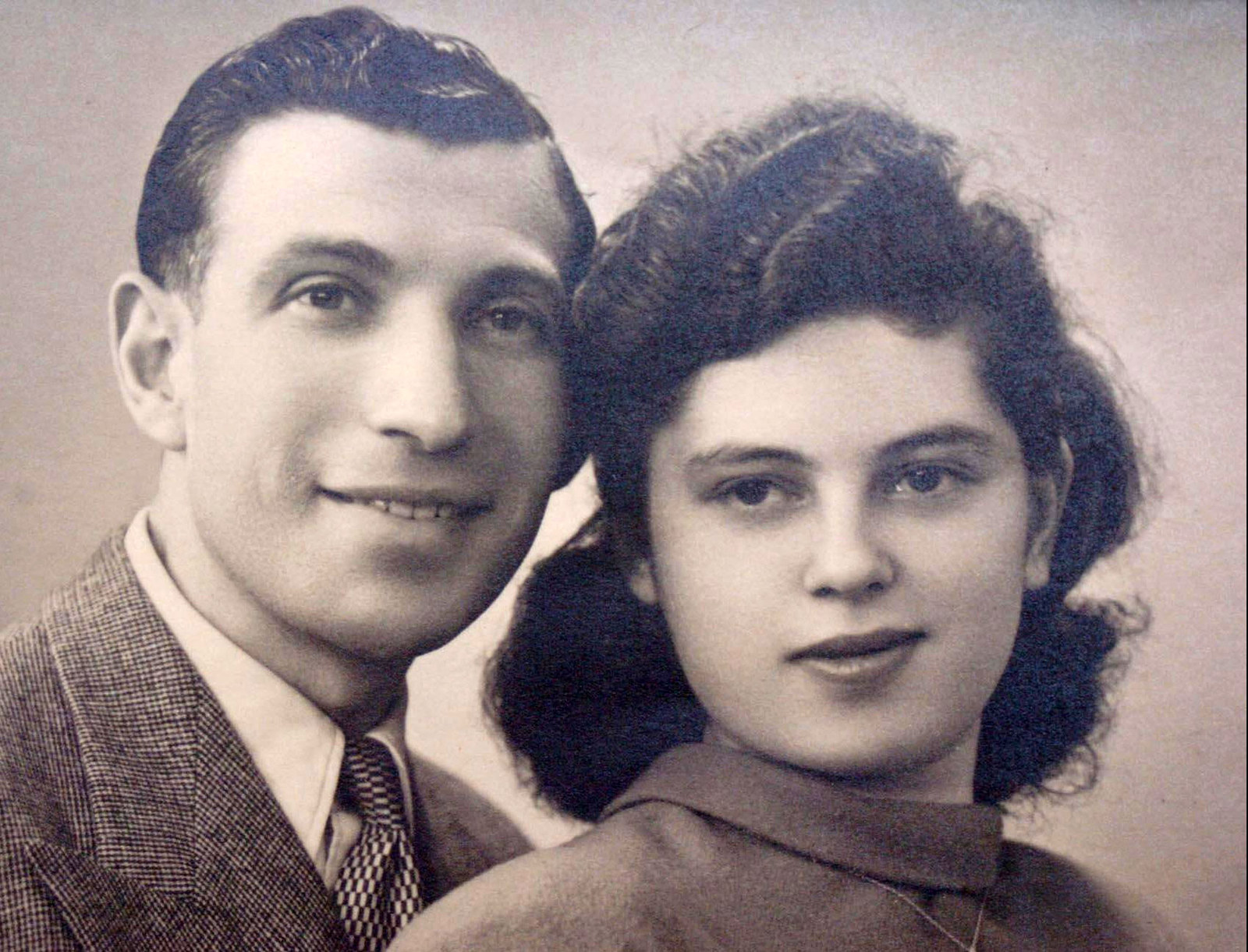

After liberation came in 1945, he returned home to discover that one of his father's employees had taken their house, and they threatened to kill him if he didn't go away. Josef eventually came to the UK, where he settled with his wife, Sylvia, and started a family.

Twenty-six years after the war, Josef discovered that his father had survived the Holocaust and even returned home to kick the trespasser out of the family house. They met in Budapest for the first time since Josef was a child.

Renee Salt, Holocaust survivor

For Renee Salt, memories of the Holocaust have never faded: "I remember everything. ... It’s so clear, as though it happened yesterday." Born in Zdunska Vola, Poland, in 1929, Renee was 10 when her world was changed on the first day of the war, 1 September 1939.

"It didn’t take them very long to overrun the whole country," she tells me. SS officers chose her family's house as a base: "From day one I lost my home."

Renee's mother had just filled their house with plenty of provisions to last the duration of the war, including a cellar full of coal. "All our stuff, including the children’s clothes, which [the officers] stood admiring in the street, [was] sent to their families in Germany."

Renee and her mother, father, and little sister had to split up and live with various relatives. Renee went to her grandparents in Kalisz.

After a few weeks the town was declared "Judenrein", meaning free of Jews, by Germany. Her mother had heard what was happening and arrived with an official pass to take Renee and her family back to Zdunska Vola.

They soon found themselves forced to live in a Jewish ghetto with eight of them in one room. Conditions were brutal. "There were shootings and beatings. ... There were a lot of men with beards, they would either burn them off ... or they would knock on anybody’s door for some scissors and they would cut the beard away, together with the skin."

Factories were created in the ghetto, and everybody had to work in exchange for food ration cards. Renee found herself in her first job at the age of 10, making socks for the German army. "The machine was bigger than I was," she says. "I had to stand on a stool to reach it. What did I know about how to make socks? Someone had to teach me for two weeks."

People from surrounding ghettos were forced into the same ghetto as Renee's family, with huge overcrowding. Only one Jewish doctor was allowed to practise. "There was no medication," Renee says. "People were dying just from simple diseases."

One day, gallows were built in the centre, the inhabitants were gathered, and 10 men were hung. The bodies were left for days for everyone to see. "We actually thought, ‘It can’t get any worse, can it?’"

In the summer of 1942, Renee remembers shouts of "Alle Juden außerhalb," or "All Jews outside." She says: "Now we had heard rumours by then that old people and young children were being slaughtered all over the country." The family took her grandparents, uncle, and 4-year-old cousin and hid them in the attic.

Following her mother, father, and sister, Renee headed outside, where they were led to a large square. Listen to Renee's account of the next events:

The group were then taken to a Jewish cemetery outside of the town. "When we got there I witnessed the first of the many ‘selections’ that I was going to go through," Renee says. "On each side of the cemetery gates stood the SS and the Gestapo with their batons, directing one to the right, one to the left. Invalids, pregnant women, people who didn’t look fit for work, old people, all went to one side, and the rest went to the other side."

Renee got through this selection with both her parents and one of her aunts. The rest of the family were on the "unlucky side".

Afterwards, Renee and her remaining family sat on the gravestones for several days, surrounded by electric lights so no one could escape. She remembers one fellow captive being happy, because "her little boy had died a few weeks ago and was buried [in the cemetery] – no one could take him away."

People around Renee tried to make her look older with make-up, a headscarf, and high heels to avoid detection. She was 12.

At one point an SS soldier spotted her and came running over, demanding to know her age. "I was paralyzed with fright, I couldn’t stand up, I couldn’t answer." Her father vouched that she was 18 years old. "This SS man looked at me very hard, it seemed like an eternity." Eventually he said, "She may remain sitting."

"I believe to today that the almighty God was holding on to me on that day," says Renee, "[and] wouldn’t let them take me away."

The group were taken to railway lines. "They never took us to stations because they didn’t want people to see what was going on."

The president of their former ghetto was called out and shot, then all valuables were collected. The group were packed into cattle trucks and taken to the Łódź ghetto around 40km away, where they were reunited with her grandmother.

Her father had a gold ring that was stuck and wouldn't come off, and an SS soldier spotted it and demanded it be handed over. He asked a fellow soldier to fetch a knife to cut the finger off.

"Now I didn’t see many miracles during the Holocaust," Renee says, "but ... as he finished saying these few words, the ring on its own, without any prompting, rolled off the finger so loosely as though it would have been at least five sizes too big, and stopped at the SS man’s feet."

Renee lived in the ghetto until 1944. "The things I saw in the Łódź ghetto are indescribable," she says.

With the advance of the Russian army, the German soldiers wanted to move the population of the ghetto. However, fearing a repeat of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, which saw German troops attacked by inhabitants, they promised better conditions elsewhere in return for cooperation in their moving.

Suspicions grew about the intentions of the German soldiers, "when the empty cattle trucks returned to take on a new load of people," Renee explains, "station cleaners found little notes in them, saying that the people were being taken to concentration camps where there was mass killing taking place. We didn’t and couldn’t believe it, which of course we should have done."

Forced by lack of food, Renee and her parents had no choice but to leave the ghetto voluntarily, so they headed to the cattle trucks again. Their destination was Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Listen to Renee's account of arriving at Auschwitz:

"Some people went to work in Auschwitz," Renee says, "but we were there just to be tortured. We never thought we’d come out alive. Experiments were going on there all the time. Medical experiments performed by German doctors, surgical experiments without anaesthetics just to observe the reactions of the patients."

Later, Renee and mother were sent to work in Hamburg, where a bull escaped from a nearby slaughterhouse. Her mother was attacked by the bull and wounded so badly she could no longer work.

After March 1945, when the Nazis knew they were losing the war, Renee and her mother were taken to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. There was no organisation, only thousands of people lying in huts dying from disease and starvation. Having been separated from her mother on the journey, Renee risked indiscriminate shooting to search the camp for her, moving from hut to hut.

After two days she found her mother on a stretcher on the edge of death. After a few days at her side, Renee spotted British tanks in the distance. Liberation came to Bergen-Belsen, but not quickly enough for her mother, who died of her injuries two days later.

Renee later settled in the UK, marrying a British soldier she met in Paris. Her husband was a liberator of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Zigi Shipper, Holocaust survivor

Zigi Shipper at home holding photos of his great-grandson (left), and in a portrait taken at the Houses of Parliament in 2014.

Zigi Shipper's story is one of brutality, murder, and horrendous conditions in Jewish ghettos across Poland.

Born in Łódź in 1930, Zigi lived with his grandparents until the age of 9, when war broke out. Jews were not allowed to continue any professional work and were banned from public transport.

The Łódź ghetto was hugely overcrowded and starvation and disease was rife. By 1940 it was surrounded by barbed wire. "People were committing suicide, especially women," Zigi says. "I couldn’t understand it then, but [I did when I got] older and became a father – would I have wanted to live if I saw my children killed?"

In 1942, German soldiers told the ghetto's inhabitants they needed 70,000 Jews to work in a factory. Zigi, believing that as a child he would not be chosen to be sent away, decided not to join his grandmother in hiding during the selection.

He was rounded up in a lorry and saw that he was joining elderly people, the disabled, and babies. Fearing the worst, he leapt off the lorry unseen and escaped. The people taken away were never heard from again.

In 1944, German soldiers announced that the ghetto would be closing. Zigi and his grandmother thought they would be better off by volunteering to be moved to a metal factory. Heading to the railway lines, they were packed into cattle trucks with standing room only. The journey has haunted Zigi: "All my life something was bothering me, up to now, even. ... How can [I], a boy of 14, hope that people should die so I would have room to sit down?" After a few days Zigi did have space to sit.

Instead of a metal factory, they arrived at Auschwitz. On getting out of the carriages, many received a beating. "You know, whenever we got beaten, even in the ghetto," Zigi says, "it never bothered us, because beating is painful but it goes away. Hunger never goes away."

Zigi was separated from his grandmother and soon came to realise the nature of the crematoriums of Auschwitz. "I keep asking myself this question: How can a human being do that ... and then in the evening sit down with his wife and children and eat their dinner and listen to music? I just cannot understand it, I never will. Even the commander of Auschwitz had his house 10 metres from a gas chamber – it’s still there."

Zigi worked in various factories and on railway lines. Listen to him talk about hunger in the camps, and the punishment for stealing:

As the Russians advanced, liberation drew closer. Zigi didn't know it at the time, but he was suffering from a severe case of typhus. German troops took them to Gdańsk on trains, and Zigi could barely walk. "Every concentration camp that was liquidated went on a death march," he says. "Either you walked or you died."

A trek to Gdynia port lay ahead for Zigi. Thanks to friends helping him, he made it alive. From there, Zigi witnessed the bombing and sinking of the SS Cap Arcona German ocean liner, which killed around 5,000 people, including concentration camp prisoners.

Zigi Shipper seen sitting at the front (left picture) and on the right (right picture) with a fellow Holocaust survivor after the Second World War in 1945.

Zigi was liberated by the British in May 1945. He recalls crawling over to a tank and saying one word in German, "wasser" (water). The British brought Red Cross parcels of food, including fruit, tins of meat, and chocolate. "There were so many people dying from overeating," Zigi says. "They were lying in the streets, with chocolate in their mouths, rich food." Having been starving for years, the bodies of survivors were vulnerable to the sudden introduction of food, and in some cases proved lethal.

"I ask people," he says, "'How did I survive having typhus?' ... When I speak to a priest or a bishop, or a rabbi, they give me an answer: 'Somebody up there wanted you to survive.'"

Zigi was eventually reunited with his mother in London, who found his name on a survivor list. He now has two children, six grandchildren and one great-grandchild. He has been speaking about the Holocaust for the last 20 years, but "it should have been 50 years", he says.

"The reason I speak to young students is I want young people to know what hatred and prejudice can do," he says. "[Hate] will only ruin your life.

"People ask me: 'Do you hate the German people?' And I say, 'Why should I?' Maybe their great-grandfathers committed a crime, [but] it’s not their fault."

He recalls a German nun approaching him in tears after giving a Holocaust talk at a synagogue. She expressed how guilty she felt, to which Zigi replied: "What have you got to feel guilty about? People like you risked their lives to hide Jewish children and babies. You should be proud of people like you."

Zigi finishes up our interview: "I say whether you are a Jew, a Muslim, a Catholic, a Christian, or whatever, either you are a good person or a bad person. Nationality and religion doesn’t come into it.

"I know there is racism and anti-Semitism, nothing has changed that way, but we, especially the young people, are the ones responsible ... to fight to change.

"There’s very little we can do about the past, but we can do a lot about the present and the future."

To find out more about the Holocaust, download 70 Voices: Victims, Perpetrators and Bystanders, a free app created by the Holocaust Education Trust that's available from Apple, Android, and Amazon and suitable for ages 13+.