It's cold and foggy in San Francisco today, after several hot weeks and several hot rainless months. The fog rolled in last week, just in time for Box's second annual developer conference at Fort Mason. When Facebook held its developer conference at Fort Mason, almost exactly a month ago, it was a warm, clear blue sky day. But last week, the fog rolled in, thick enough that you couldn't see the peak of Mt. Tam across the Bay in the promised land of Marin county.

Things change. And never more quickly than today. As the tech industry spills out over into just about everything else, eating its way into fashion and logistics and nutrition and education alike, instead of helping us make sense of the world, it just makes things muddier. The industry has spent decades promoting its ability to make the world a better place. And certainly, it has done that for communications. We can talk to nearly everyone, nearly everywhere, nearly all the time. But is that better? Or just more? As Nepal collapses and Baltimore burns, we are still able to do little more than document it. We survey the damage from far overhead, from thousand-dollar personal aircraft outfitted with high definition personal video cameras. We Periscope the riots. Or pretend to.

And of course a Periscope labeled Baltimore riots is a gross white dude with his shirt off lying in bed

The spirit of the age is a collective uncertainty. It's a shrug. Nobody knows. It's an unease about where we are going — and where the hell are we going? There used to be obvious, inevitable things we could point at and say: This is the future. Right here. This great inevitability will dominate our lives for the next two, three, five or ten years. Believe it.

We did once. We believed it about IBM and we believed it about Microsoft and Google and Apple and Amazon. But what do we believe it about today? Is it Snapchat? Is it Uber? Is it Facebook? (It is probably Facebook.) Is a chat app really worth billions of dollars? Really? Well, sure. It is because people say it is.

So what happens when they say it isn't?

Anyone who pretends to know the future is fooling you. Or themself. We are barely muddling our way through the present.

Nobody knows. This is the only true thing anymore. Nobody knows, and you need look no further than the Apple Watch on your wrist to see it. The Apple Watch — the biggest gadget story of 2015 — reveals just how little we know.

No one in tech journalism knows quite what to make of the Watch. That's partially because it is from Apple and for many years now Apple has done only delightful things. And so perhaps if you don't like it, you are just wrong. Wrong, like the idiots who decried the iPod and the idiots who decried the iPhone and the idiots who decried the Apple Stores and who, years later, are still publicly shamed for being Wrong About Apple. No, it's better to land somewhere in the middle than be wrong. Reviews have become about the reviewer, and securing a place in line for the next Apple device — or at least the next job.

And so the tech press, which ostensibly exists to help us understand, has spent the last several weeks throwing tens of thousands of words at this watch, without really saying anything. At the end of these massive editorial productions, as the end credits roll, more often than not we've been left without any meaning, any takeaway, any sense of whether or not we should actually buy the damn thing: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. The best tech journalism on this great unknown device so far comes from those who are not in tech, or those who are not in journalism.

And what about Oculus and Hololens and Magic Leap? What about our augmented, virtual future? (Hint: Slap some cardboard on an Android handset and you can at least squint at it now, if not fully view it.) At NewFronts yesterday, the New York Times announced it was rolling out a virtual something-or-other and everyone shrugged because, well… Maybe? Who wants to be wrong? Nobody knows.

(Except, of course, in this case, we do. We've seen enough pictures to know that if Google can't convince us Glass is a good idea, Facebook will have even bigger problems getting the world to strap giant black boxes across our faces so that we can all be alone together, mouthes agape.)

But nobody knows, despite all the sooth-saying from venture capitalists on Twitter, who spew buddhaesque aphorisms and argue that the bubble isn't here, and the bubble isn't coming, and that this great dome rising above us will never come down.

And maybe it won't. Nobody knows.

Maybe it won't matter that the EU intends to take a crowbar and hammer to Google. Maybe it won't matter if we merely bounce from outrage to outrage on social media, seeking and seeking without ever focusing. Maybe that watch will look great on you.

But back to last week.

Box went public this year, at long last, after many delays. Only to be poked at by The New York Times which described its developer conference in Hail Mary terms. But you wouldn't know it to look around. Food trucks were parked all across Fort Mason's parking lot, offering free food to (paid) attendees. A giant sign on the interior wall asked, suggestively, "Which industry will you change forever?"

And when the event itself began, Box's charismatic CEO, Aaron Levie, bounded out across the stage, singing along to "California Love." It's a great song, even if Tupac is dead.

After Levie (wearing a dark suit, blue shirt open at the collar, and orange-laced Tigers) interviewed Google chairman Eric Schmidt (wearing a dark suit, blue shirt open at the collar, and loafers) onstage, and after they talked about Edward Snowden and life-extending drugs and machine learning and enterprise software development, and after Levie again took the stage to announce a set of developer tools, and after a parade of Box execs took the stage, and after Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff (also wearing sneakers) took the stage, Levie walked outside and sat on the edge of the water.

There, sitting on an enormous, person-wide tree stump that had been ridiculously cut into an simulacrum of a chair and plopped out on the edge of a pier, he talked about the decision to take Box public.

"It's a natural evolution," he told BuzzFeed News. "When we decided to go public we were nine years into the company, and we'd had investors for seven or so years. We were operationally ready, and our business model had a certain amount of scale — last year we did about $215 [million] in revenue — so we were at a scale where we just made sense more as a public company than a private startup. Some companies get pushed out to go public, some companies the CEO has always wanted to run a public company. I think we're somewhere in between. For us it was more of a level of readiness as a company."

"I think it was just a natural evolution more than anything else, I think it's the same reason that Salesforce and Workday and Google and others eventually went public. Right now you have some companies that are going through such amazing growth rates and growth curves that we're not talking about private as much, because you're able to raise as much capital as you need on the private market — you don't need to go public from a capital standpoint. But eventually usually you go public because that capital has to convert to something more liquid at some point."

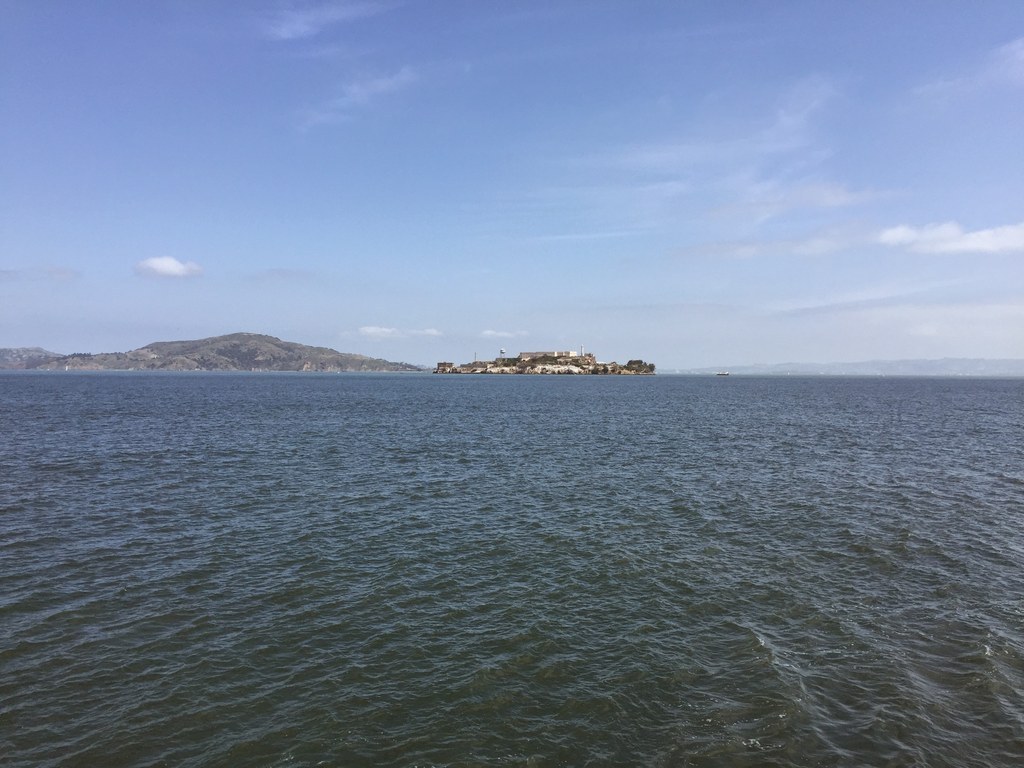

That, actually, seemed like something you could know, and something you could count on. Money put in has to come out again. That's where things have to go if you want to keep moving. We both sat there on our enormous tree-chairs, looking out at Alcatraz. The fog had lifted over this part of the Bay, and it was nice out, if a bit chilly.