"If I could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.”

This quote, by the American painter Edward Hopper, sums up art therapy, a type of therapy that uses artistic media to explore and interrogate difficult and complex emotions. Art therapy plays an important role in the treatment on offer at Tyrwhitt House, a Combat Stress facility for veterans who are recovering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Combat Stress is a mental health charity that offers free help and advice to UK veterans.

Tyrwhitt House is a grand yet inviting building in Leatherhead, on the outskirts of London. The length of a stay at this centre varies from two weeks to six weeks and treatment programmes include psychoeducation (helping patients understand their symptoms), one-to-one counselling, mindfulness training, and art therapy.

BuzzFeed visits the house in early October to find out exactly what art therapy is and how it can change the lives of people physically and mentally scarred by conflict.

I meet senior art psychotherapist Jan Lobban, who talks me through the sessions offered at Tyrwhitt House. “It’s not about how good the art is, it’s about what it represents," she says. "It’s about self-expression and being able to externalise some things that might not be making sense. People learn about themselves through image-making.”

Many veterans we speak to describe hiding their PTSD under a mask, hoping to keep their trauma inside. Art therapy allows them to take that mask off, visualise what they’re feeling, and, in doing so, begin to process it.

The lessons are theme-based, but the veterans aren't aware of the theme beforehand. The aim is to get an instant, spontaneous response and to overcome any reservations. Themes include “rhythm” and “journey”, and one session involves veterans choosing inspiration from a stack of postcards.

After 15 minutes of collecting thoughts, veterans have 45 minutes to get creative. “I like the condensed speed you have to work in," Tom says. "When you come in, you have a very short space of time.”

Some of the veterans were wary about art therapy at first. “To be honest I was a bit sceptical," Graham says, "but I was happy to be here. I quite liked drawing and I just thought it would be nice to relax.”

However, the sessions aren’t always relaxing. “The inspiration comes naturally, or quite instantly," Tom says, "and sometimes you have to get up because it’s too painful.” Graham agrees: “You get put on the spot a little bit. I got choked up yesterday and then Mark got choked up and we all set each other off. So actually it’s really, really emotional.”

“The inspiration comes naturally, or quite instantly, and sometimes you have to get up because it’s too painful.”

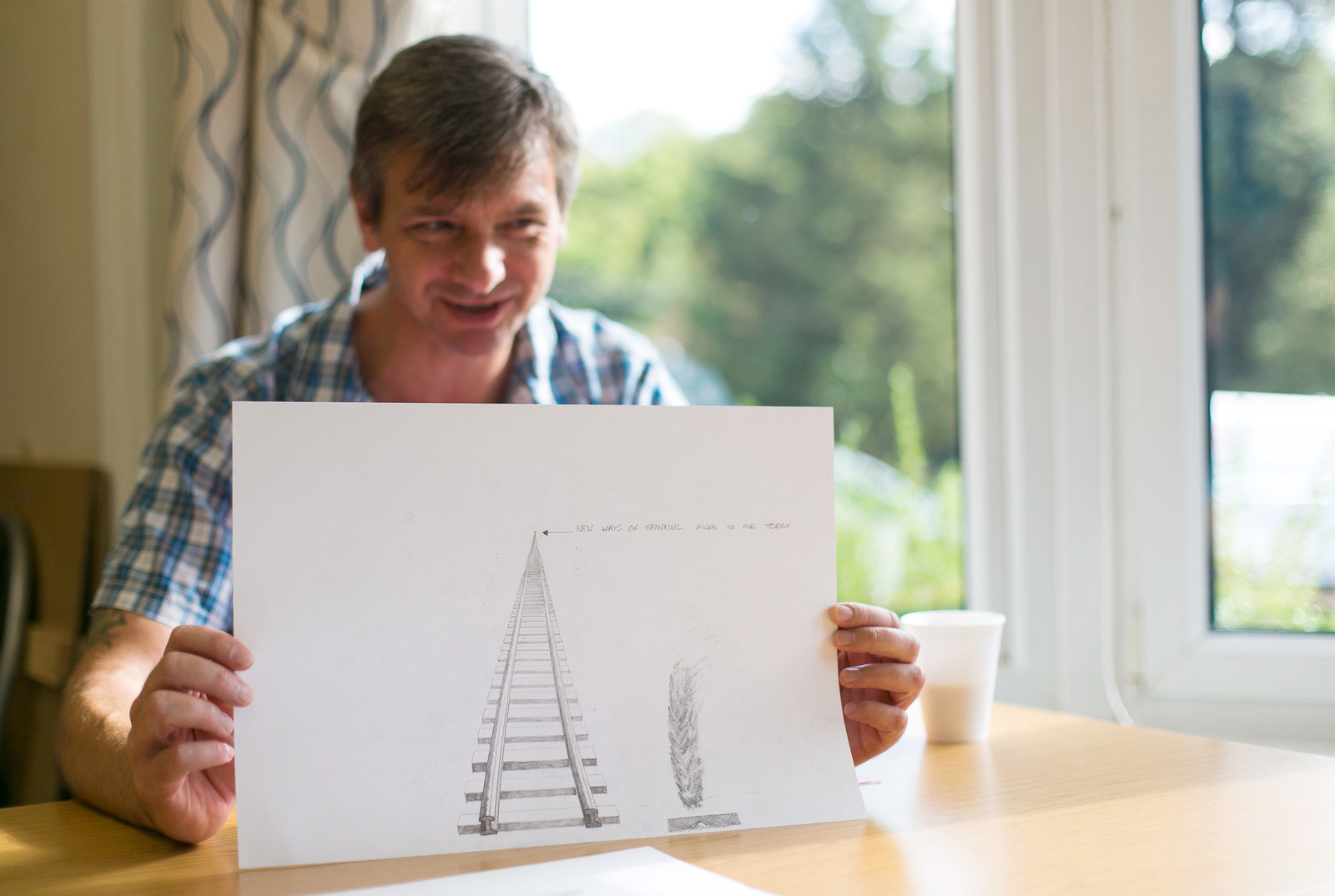

Yesterday’s session was clearly a difficult one. It began when Lobban announced that the theme would be “journey”. Immediately Graham began to worry: “I’d literally just been on a journey. I came out of counselling and I’d been given some other ways of thinking about things. I was dreading coming in here. I felt a bit upset. As soon as Jan said, 'It’s going to be about a journey', I could feel myself welling up.”

Once the session was over Graham continued to think back on his traumatic experiences but in a slightly different way: "Sitting in my bed I started to feel pity and forgiveness rather than fury and anger. I think forgiveness is the wrong word, but I’d rather feel that than fury.”

The veterans credit the group setting for pulling them through challenging sessions. There’s a great sense of camaraderie. Mark says: “Being in a group helps – you can relate to the others when they’re talking about their work afterwards.” Even after yesterday's challenging session, the group managed to lift Mark's spirits: “When it got to the end I got choked up and then the lads sort of gave me a clap. Made me feel better.”

Graham talks about a fellow veteran who, instead of drawing, wrote a poem that struck a chord with the group. “It was fantastic," he says. "And then he deleted it. I knew he would.” Mark chimes in: “Straight away we said 'print it out' and he deleted it.” For some of the patients the art they create might be framed or displayed, but for others it’s just a snapshot in time, and one they’d rather forget.

Lobban's art studio is filled with pots of paint and boldly coloured papers, with various art projects framed on the wall. Despite this abundance of creativity, it’s not a requirement in her classes to have artistic flair. Lobban says: “The group is so supportive – people don’t feel embarrassed about stick figures.”

Kevin responded to Lobban's theme of "journey" with a landscape of Malawi, where he was stationed as a royal engineer. “I’m not an artist by any means," he says, "but you do have some thoughts or images in your mind, so I personally think to myself, There must be some way of putting these images on to paper.”

In fact, the most important part of art therapy seems to be explaining your work to the rest of the group once you're done. Mark says: “I have to talk about it even though I know it’s going to be challenging, but you think, No, get it out there. It’s like letting a bit of pressure off. It makes you feel better afterwards.”

"It’s like letting a bit of pressure off. It makes you feel better afterwards.”

Simon speaks about a Rubik's cube he drew that he saw as a metaphor for his PTSD. There are 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 combinations in a Rubik's cube. To him PTSD is also made up of a myriad of combinations, because there are many, many different ways people experience it. Additionally, the cube reminded him of his own desire to fit in, especially in life after combat. "Everyone needs to find their own way," he says. "Combat Stress gives us the directions."

Art therapy isn’t just about creating your own art; it’s also learning to find meaning in other people’s work. "What I’ve learnt here is the ability to look at pictures and see their meaning," Mark says. "Not just the actual picture itself but get the feeling out of that art.” He has plans to visit London soon: “I want to go to the National Gallery. I’ve never been there. I really want to go there and have a good look around.”

Going out, going to exhibitions, and finding the enjoyment in life is a big deal for patients here. “PTSD makes your life really small,” Graham says. “You stop enjoying the things you want to do. You try to go out but you have such negative thoughts you just can’t. This will be the death of you if you let it get hold of you, you know."

Lobban says: “This whole programme is all about challenging yourself, reclaiming your life, and learning strategies so you can do the things you want to do.”