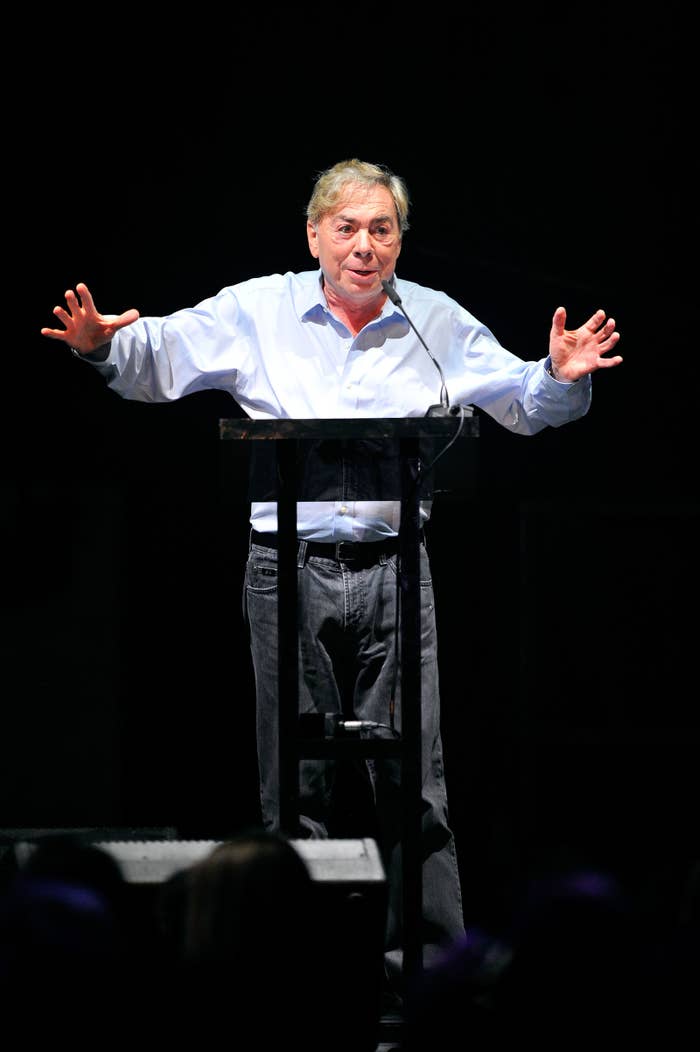

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s name has become so synonymous with hitmaking that researchers at Cambridge University created a computer program to compose a theoretically guaranteed smash musical theater score and dubbed it “Android Lloyd Webber.”

But, an amused Lloyd Webber noted, the scientific effort to come up with a formula for a bona fide hit is “absolute rubbish.”

“I'd like to know whether that computer would have actually sat down and said, ‘In 1980, the next good idea was a musical with human beings dressed up as cats reciting the poems — set to music — of T. S. Eliot, directed by the director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, in a theater that has never had a hit in it,’” Lloyd Webber told BuzzFeed News with a sly smile from a seat at Nougatine, the tony restaurant at the Trump International Hotel.

Indeed, Lloyd Webber’s description of Cats might sound silly on paper, but there’s no denying the musical’s lasting impact: It earned seven Tony Awards, including Best Musical, in 1983, and after its initial 20-year run — the fourth longest in Broadway history — Cats now has a revival slated for Broadway this fall. The composer’s biggest hit, The Phantom of the Opera, is the longest-running Broadway show of all time with over 11,500 performances. Other eclectic subjects from Lloyd Webber’s crowd-pleasing musicals include Bible stories (Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and Jesus Christ Superstar), the wife of an Argentinian dictator (Evita), and a 1950 Billy Wilder classic (Sunset Boulevard).

It’s too soon to say if his most recent undertaking, School of Rock — a musical adaptation of the 2003 Jack Black–starring comedy — will come close to the success of Phantom, but it’s been selling well and earning largely positive reviews since its December 2015 opening at Broadway’s Winter Garden Theatre. No matter how long the show runs, Lloyd Webber already considers it a win.

“With School of Rock, I just thought, Great story. It’s got a couple of really good songs in the movie, but it hasn’t really got a score,” he said. “I thought, I’ll just have fun and I’ll write it.”

Lloyd Webber’s passion-based approach to his projects hasn’t always led to critical adoration and record-breaking ticket sales. His 2010 sequel to Phantom, Love Never Dies, was — by his own admission — a “big catastrophe” when it debuted in London. His most recent musical prior to School of Rock, the ambitious historical drama Stephen Ward, earned mixed reviews and closed in London just three months after its opening; Lloyd Webber said the show, based on the 1963 Profumo affair, “didn’t work.”

“I want to do something that is going to challenge me,” he said, reflecting on Stephen Ward’s complicated subject matter, his voice reflecting genuine excitement even as he discussed commercial failure. “I’m in a lucky position that I can actually write what I want. And then if it’s a hit, great. And if it’s a complete flop, a turkey, it doesn’t matter, really.”

Of course, not everyone can afford to take the risks that Lloyd Webber does. Producing new theater is prohibitively expensive, and complex shows that may or may not recoup their costs often have trouble finding investors. For his part in making theater more accessible to undiscovered talent, Lloyd Webber is exploring ways to help support up-and-coming writers and composers. Along with his company, Really Useful Group, he has bought a small theater in London, the St. James, which they’ll take over this summer and begin to use specifically for theatrical development.

“We’re just gonna make the theater available for people who want to take it. It’s only 300 seats, and I’m gonna suggest to them, ‘Don’t have sets, don’t have anything like that, but just try your work out,’” he explained. The move was inspired, in part, by the way School of Rock skipped the standard out-of-town tryouts in which shows are fine-tuned outside of New York City: Instead, they opted to develop at the Gramercy Theatre, where the stripped-down work-in-progress was performed (and altered) in front of nightly audiences prior to its Broadway debut. “Nine out of 10 [shows] probably won’t work, but if we can find one show that works and we get rid of all of the paraphernalia that surround doing a musical, then we can encourage new people into the theater.”

He also encourages fresh takes on his established properties. There are 36 productions of Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals currently running at theaters around the world, he said, and he’s given up on seeing all of them; at this point, he’s used to relinquishing a certain amount of control.

He recently met with Tony Award winner Andy Blankenbuehler, who choreographed Hamilton among other shows, to discuss the Cats revival. Lloyd Webber concedes it’s “too soon to tell” what alterations will ultimately be made to the show, but noted, “I don’t want to really interfere with it too much. I’ve done School of Rock, and I don’t want to be all over this one. [Andy] said he’d love to be involved with it, so whilst it’s still going to be based on the original Cats … he’s going to hit me with what he wants to change.” He laughed at the notion.

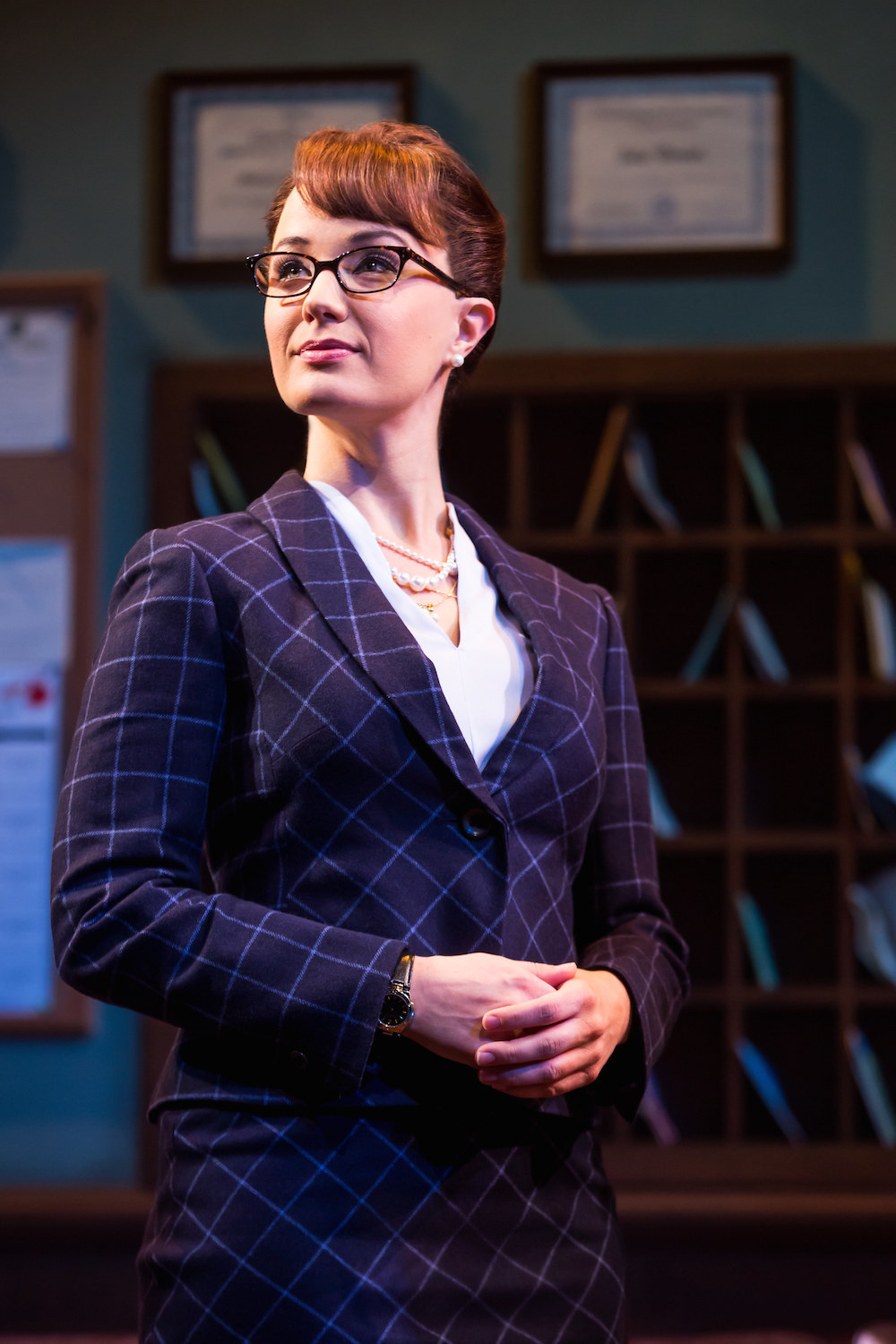

School of Rock has already earned its own alternative version, as Lloyd Webber made the amateur rights to it available prior to its Broadway opening. On March 3, just three months after the New York premiere, the Oakland School for the Arts performed the first youth production of the musical at the Curran Theatre in San Francisco.

Releasing the amateur rights early in a show’s run (and especially before its opening) is a highly unusual move. But for Lloyd Webber— who noted the first performance of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat was in a school — the decision was easy. “I’m looking forward to seeing a few productions of [School of Rock]. I just hope everybody does it their own way,” he continued. “Don’t copy the Broadway show. Go out and do something better.”

As an example of “doing it better,” Lloyd Webber said the most recent production of Love Never Dies — which debuted in Australia and will make its way to Washington, D.C., next year — is a major improvement over the London run. (The differences between the productions are hard to articulate, he notes, because “the fine line between a musical working or not is very small, but the consequences are very large.”)

While he’s intrigued by fresh takes on his shows, Lloyd Webber is most excited about new ideas on Broadway — whether they’re his or somebody else’s. He repeatedly cited Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton as “the first time I’ve heard a really truly original new voice in musical theater in many, many years.”

Hamilton is also, in a way no one could have predicted, an unprecedented success. Lloyd Webber said truly inspired ideas — the risky ones that subvert the classic ideas of what a musical should be — lead to shows that connect most with audiences. “What Lin did is his own. It’s his own world,” he said. “The great [musicals] are always that ones that come off the wall.”

It’s when talking about original and transgressive work that Lloyd Webber became the most animated. “Write what you want to write. Go against the grain if you can. … There are no rules in musicals at all.”