Bar Picas is a glass and wood cube in Lima's Barranco district that sits in the shadow of a picturesque church with a roof that is slowly collapsing. After he had the bar up and running, its owner, Carlos Bruce, approached the Archdiocese of Lima with a proposal to restore the church and rent it for 10 years as a multiuse space.

They said no.

Perhaps they suspected Bruce would turn the church into a bar like Picas, which hosts regular "fashion shows" featuring muscled boys in boxer shorts and girls in bikinis. Or maybe it was because Bruce was already on adversarial terms with the head of the country's Catholic Church, Cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani.

Nightclubs are just a side business for Bruce; his main occupation is politics. Since 2006, he has been a member of the Peruvian Congress. He had a serious shot at becoming the country's vice president when former President Alejandro Toledo asked him to be his running mate in his failed bid to recapture the office in 2011.

Bruce has showed no fear in baiting the Catholic Church in one of the Latin American countries where it has the most political power, and not only by trying to rent one of its churches. Over the past few years, he has emerged as the leading advocate of LGBT rights in the Peruvian Congress. After unsuccessfully championing protections for LGBT people in hate crimes legislation and a failed proposal to create a new kind of contract to allow same-sex couples to secure their joint property, Bruce introduced a bill to allow same-sex couples to enter into civil unions in September.

Cardinal Cipriani went nuclear.

"It doesn't seem to me that we have named congressmen in order to justify their own [sexual] preference," Cipriani said during a Sept. 14 television appearance.

Rumors that Bruce — who is divorced and has two adult sons — is gay have circulated for years among both his enemies and his allies. But this is the first time any public figure had so directly said it on the record.

Cipriani's remarks set off a media storm. The front page of the tabloid La Razón blared, "Cipriani pulls Bruce out of the closet." Social media went into a frenzy, circulating a picture of the congressman at his bar with a group of men who look as though they were dressed for a leather party.

A popular comedy show also featured a skit in which an actor portraying Bruce addresses a group of effeminate sailors who refer to him as their "godfather."

At first, Bruce responded angrily to what he termed "personal attacks." He announced his "irrevocable" resignation from La Razón, where he had been a columnist, and said the cardinal's words were "beneath him."

"I will not fall to the level to which the cardinal has descended," he said on RPP Television. His reaction seemed to suggest he thought he was fighting for his political life.

But as Cipriani's statement faded from the news — helped by the fact that the Peruvian church became embroiled in a child sex-abuse scandal — Bruce's public response appeared to grow more confident. Last week, he even crowned the winner of the Miss Amazonas drag beauty pageant in the Amazonian city of Iquitos, which he described as part of his nationwide campaign to promote the civil union bill.

Bruce has managed to carve out a space in Peruvian political life that would have been close to unthinkable in the United States 20 or 30 years ago, when gay rights were as controversial a subject in the U.S. as they are in Peru today. (Congressman Barney Frank would be the closest analog before he came out in 1987, but even he was leery of taking the lead on LGBT rights legislation when closeted.) Bruce believes that being identified as gay would be political suicide, and yet he does very little to dispel the impression that he is. And he has been unafraid to lead on LGBT rights despite its potential to keep him from ever climbing to higher office.

When asked directly whether he is gay, Bruce has a standard answer. "My official response is, 'I don't speak about my personal life,'" Bruce told BuzzFeed during a conversation in the Peruvian capitol building in Lima last year.

There's a big political difference between supporting LGBT rights proposals and being openly gay in today's Peru, he explained.

"If I can imagine a politician saying he's openly gay, for sure he [would lose] 80% of his voters," Bruce said.

Bruce can afford to tackle the issue because his popularity runs deep. He had the second-largest vote total of any member of Congress when he was elected to his first five-year term in 2006, and his tenure in Toledo's cabinet made him a household name.

Bruce hadn't set out to be a politician. He was trained as an economist and made his fortune in the seafood business. He began his political career while president of the country's exporters' association. During the 2000 election, many business interests turned against then-President Alberto Fujimori, who had fought ruthlessly against the Shining Path guerrillas during the country's civil war in the 1990s and was then running for a third term in violation of the constitution.

Bruce offered his support to Toledo — Fujimori's leading opponent — and ultimately ran his campaign. Their relationship became even closer after Fujimori recaptured the presidency in a questionable election: Toledo and his team had to go into hiding after the government blamed them for a bombing that occurred during an anti-Fujimori protest. After a week of secretly camping out at the Park Hotel near the U.S. Embassy, it was decided that Bruce would take the risk of leaving the hotel to be the spokesman for the Toledo camp.

Facing widening corruption charges, Fujimori fled to Japan before later being extradited and imprisoned in Peru. Toledo won the election that followed. When he entered office in 2001, he named Bruce to head the Ministry of the Presidency, a position that put him in charge of overseeing all Peru's regional governments and was one of the most powerful agencies in the country. When democratic reforms did away with the agency, Bruce became the first minister of housing.

That's where he won popular affection. He went on television to publicize a program subsidizing the purchase of homes accompanied by the program's mascot, who dressed in a costume like Bob the Builder's and was known as "T-Chito," a play on words: "Chito" is sort of the Peruvian equivalent of "homie," and "techito" means "little roof."

That's the name that stuck to Bruce. Even today, when he walks around Lima, strangers call out to him, "Hey, Techito!"

He rode that popularity into Congress from a district in Lima, a city that remains a center of Catholic and evangelical organizing. Though a handful of jurisdictions have local laws banning discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, reports of anti-gay hate crimes are frequent (and often horrific) and opposition to LGBT rights is widespread. A 2011 proposal from Lima Mayor Suzana Villarán for an ordinance to ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation helped prompt a recall election that she only narrowly survived and cost her party many seats on the city council.

Christians in Lima "do not agree with a mayor that participates in marches of transvestites and sissies [maricas], a pro-lesbian, pro-gay mayor," one of the recall leaders said in a November 2012 interview. "Thanks to … evangelical churches' pro-life and pro-family movements, everything has headed towards [her recall]."

Yet when Bruce's opponents have tried to make an issue of his sexual orientation, it has backfired.

On Jan. 17, 2011 it was reported that Luis Castañeda Lossio, a presidential candidate from Solidaridad Nacional, a center-right party, called Bruce "una loca" during a press conference, a phrase that literally means "crazy" but is used like "faggot." The press pounced, eagerly reporting on the comments and Bruce's denunciation of Castañeda's comments as "homophobic."

It wasn't entirely clear if Castaneda intended the epithet, however. It came while he was responding to a statement Bruce had made that Castañeda was nervous about his standing in the polls. The full quote was, "Esa es una loca — es una loca afirmación," which could be translated, "That is a crazy — that is a crazy assertion." Whether he meant to impugn Bruce's sexuality depends on whether the pause in phrasing was intentional.

Despite the ambiguity, Castañeda came out looking the worse for it, publically criticized for violating decorum and repeatedly forced to deny that he ever called Bruce a "loca" in the first place. Bruce, on the other hand, remained unconcerned about how discussion of his sexuality might affect the campaign — in fact, the encounter may have emboldened him. Just over a week later, the Peruvian equivalent of the "It Gets Better" Campaign, Todo Mejora, posted a video from Bruce in which he seemed to be daring his critics to bring up his sexuality again.

Addressing his remarks to a young gay person who is being bullied, Bruce said that "Many bad people sometimes [spread hatred] against people who are different." But, he said, raising his eyebrows, "I know businessmen, politicians, that are gays. And they are successful people and are very respectable people."

The bullies, he said, are the ones who can't get jobs in later life. But the kids who are bullied wind up more successful and happier than the bullies. "My advice," he said, "is to laugh" at the insults.

Despite the controversy following Bruce's introduction of the civil union bill, it seems like it has a more serious shot of passage than any other recent major LGBT rights legislation. Or, at least, advocates appear to be mounting a better-organized campaign around the bill than they've managed to do around other initiatives in the past.

The Peruvian LGBT rights movement is beset by division, in part because there are many different groups run mostly by volunteers. They disagree on priorities and strategy; there are divisions between, gay, lesbian, and trans interests; and class issues often trump LGBT-specific concerns in their politics.

Peru's oldest gay rights group, the Movimiento Homosexual de Lima, spurned Bruce's ticket in 2011 to endorse the ultimate winner of the presidential race, Ollanta Humala, even though Humala voiced strong opposition to same-sex marriage following a special breakfast meeting with Cardinal Cipriani. Humala's policies were more progressive, explained MHOL's Veronica Ferrari, and, "MHOL is basically of the left."

For the civil union effort, Bruce is collaborating with MHOL, along with the most professional NGO in the LGBTI rights world, the Center for the Promotion and Defense of Sexual and Reproductive Rights, which is known as PROMSEX. A small, relatively new organization, the Secular and Humanist Society of Perú, is also a key player because its founder, the British-educated Lima native Helmut Kessel, has advised Bruce on LGBT issues since his vice presidential campaign and has been instrumental in strategizing behind the scenes.

Congress isn't due to take up the civil union measure until March, but the campaign for its passage is already in full gear. They face an uphill fight — a September poll found 65% of Peruvians opposed to the bill, and 45% said they agreed with a statement by Pope Francis that gays and lesbians are "socially wounded."

The measure's backers have started a social media campaign similar to the one mounted by the Human Rights Campaign before the U.S. Supreme Court's rulings on same-sex marriage in June, having supporters change their avatars to an adaptation of the Peruvian flag that looks like an equals sign.

In late September, the coalition also pulled together an impressive list of almost 200 public figures as signatories for a declaration calling for the law's passage. The list, published in El Commercio, was headed by Nobel Prize-winning author Mario Vargas Llosa and include the names of 17 members of Congress, plus Bruce. Another important signatory was Diego García Sayán, president of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which has two cases in the works that could lead to a ruling that same-sex marriage is a right under international law throughout the Americas.

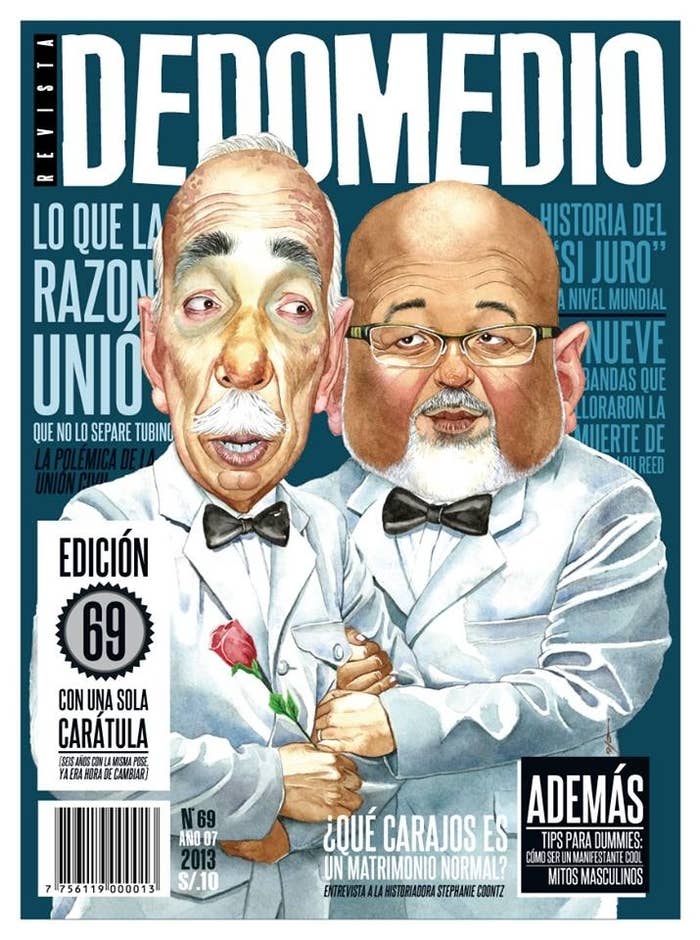

The civil union campaigners launched their latest initiative this week. They purchased billboards around Lima featuring "Imaginary Couples" — famous straight people posing as same-sex couples alongside the moto, "To love is not a crime." Participants include Congressman Kenji Fujimori (Keiko's brother and Alberto's son) paired with retired footballer Miguel "El Conejo" Rebosio, and comedian Jorge Benavides with boxer Juan Zegarra. The campaign has gone viral under the hashtag #parejasimginarias, and spawned a parallel meme, #parejasreales, featuring actual same-sex couples.

They're keeping their feet on the gas despite the controversy over Bruce's sexuality. In fact, this has proved a boon, said George Liendo of PROMSEX.

"It hasn't [damaged] the image of Congressman Bruce, but rather I think it made it stronger," Liendo said. "If characters didn't exist like the cardinal, members of congress from Opus Dei, or evangelical members of Congress ... with their extremist commentaries like 'homosexuals are sick," "they're damaged goods" … the media debate would not exist."

And since the dust-up over Cipriani's comments, Bruce hasn't seemed all that eager to keep questions of his sexuality out of the media; perhaps he is beginning to think it's to his advantage, as well. At times, he has seemed to actively court the controversy.

In early October, Bruce participated in a segment of a Peruvian news program called "In Private," devoted to the personal lives of public figures. The host, Mónica Delta, broached the topic of his sexual orientation by saying, "I have read or heard that you've said that it doesn't bother you to be called gay."

"Indeed," Bruce confirmed. "Sometimes they direct insults at me or believe they are insulting me by saying, 'You are gay.' But I am here to tell you I don't take that as an insult."

"If you were [gay], would you say it?" Delta gently pressed.

"I think that's an intimate part of a person's life," Bruce said. But he added, "What I would never do is say I am something that I'm not."

"And what is it that you are not?" Delta asked.

"Well, I am not a very disorganized person," Bruce said.

J. Lester Feder is a foreign correspondent for BuzzFeed and 2013 Alicia Patterson journalism fellow.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly identified the president of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. He is Diego García Sayán.