NAIROBI — George fled his home in eastern Uganda when his aunt found out he was gay and called the police. He was 18 at the time. First he made his way to Nairobi, where he was forced to sleep on the streets. When he finally got to a refugee camp in northwestern Kenya, it was a relief.

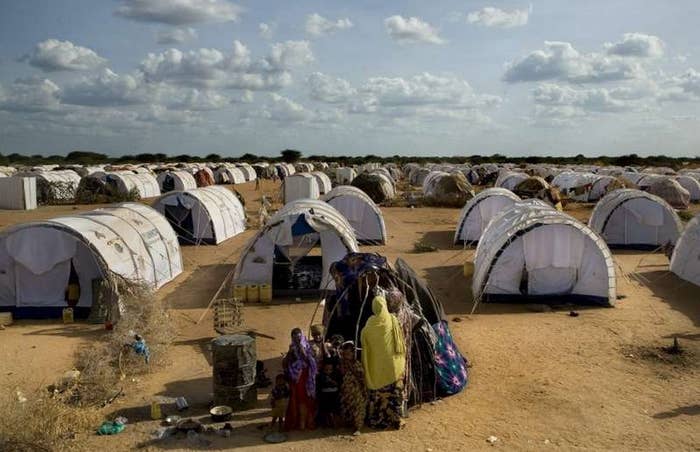

But now, after several months in a desert facility that houses hundreds of thousands of refugees from countries including Ethiopia, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, George is too frightened to even go regularly for food and water. (George's real name has been withheld to protect his safety.) People call him names, he told BuzzFeed from a borrowed cell phone, and throw dirt at him. A man recently struck him so hard in the stomach with a bottle that he wound up in the hospital. He is afraid of going to the police for protection — homosexuality is technically a crime in Kenya, and other LGBTI people in the camps have warned him that authorities will arrest him.

"I'm tired of this life, honestly," he said. "I feel like poisoning myself."

This is what refugee life looks like for many LGBTI people who have fled Uganda. Some activists from Uganda and other countries where anti-LGBTI sentiment is on the rise can quickly reach Europe or the United States if they have money or international connections, but most go to neighboring countries that aren't much safer than where they left.

George was part of a wave of LGBTI refugees who fled Uganda in the months surrounding the passage of the Anti-Homosexuality Act, a new law that imposes up to a lifetime sentence for homosexuality. The proposal, which originally included a maximum punishment of death by hanging, was finally signed by President Yoweri Museveni in February. It had been pending since 2009. As anti-gay sentiment intensified in the lead-up to the bill's passage, many men and women were harassed or arrested under the law criminalizing sodomy that had been on the books since Uganda was a British colony. Across the border, Kenya seldom enforces its version of the colonial sodomy code, though there is concern that could change as some lawmakers are calling for a crackdown on LGBTI people in light of Uganda's law.

In some ways, Ugandans who flee to Kenya are more fortunate than LGBTI people who seek asylum in other African countries. In Kenya, petitions for asylum are processed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees instead of the Kenyan government. Though sodomy is against the law in Kenya, UNHCR recognizes persecution on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity as a basis for asylum under international conventions. Despite abuses in the refugee camps, UNHCR has a point-person for LGBTI issues and is attuned to their special vulnerability. While UNHCR Deputy Representative to Kenya Able Mbilinyi said the agency has "recorded a number of similar complaints from Kakuma" about abuse of LGBTI refugees, and the agency considers it "an issue that needs a lot of sensitization of law enforcement agencies."

But the situation in Kenya is volatile. After Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Act became law in February, a group of Kenyan lawmakers proposed similar legislation and anti-LGBTI marches were organized. The government moved to quash the proposal, but the majority leader of the Kenyan assembly, Aden Duale, called homosexuality a "social problem" as "serious as terrorism" in the course of the debate. Kenyan LGBTI activists believe the bill could become a real threat along with rising anti-gay attitudes among the general public.

"The political climate is a bit unstable," said Human Rights Watch's Nairobi-based LGBTI researcher Neela Ghoshal. Though Kenya is currently "100 times better than Uganda" for LGBTI people, Ghoshal said, "we still have a law against same sex conduct. It's not enforced, but it could be enforced at any time."

While there is no firm count of the number of LGBTI Ugandans crossing the Kenyan border in recent months, Njeri Gateru of the Kenyan NGO the National Gay & Lesbian Human Rights Commission, said that in her previous work with a refugee organization she would normally encounter five LGBTI Ugandans seeking asylum each year. In the past three months, she said, she has personally "interacted with 20 in the past two months."

This influx is straining the resources of LGBTI organizations primarily focused on fighting for the rights of LGBTI Kenyans, she said. And there is the risk that a visible influx of LGBTI refugees "really could make [Kenya's climate] worse," though her organization is committed "to trying to do whatever we can" to serve this new refugee population.

Kenya's LGBTI refugee population is also running headlong into a wave of hostility to asylum-seekers for reasons that have nothing to do with sexuality. Last month, following terrorist attacks in the southern city of Mombasa allegedly linked to the Somali Islamist organization Al-Shabaab, the Kenyan government ordered all refugees in the country be confined to refugee camps like the one where George now lives. Several Ugandan refugees who were detained in refugee roundups last month reported to advocates that Kenyan police assumed they were gay because they were from Uganda, and even tried to force them to submit to medical exams they believed would determine their sexual orientation — a tactic widely used by Ugandan police when arresting people accused of homosexuality.

These factors make refugee life dangerous even for those with well-documented cases of persecution who should be strong candidates for resettlement in North America, Australia, or Europe, an option available to only a tiny portion of refugees. Governments worldwide resettle between 80,000 and 90,000 refugees each year, equal to less than 1% of the more than 15 million refugees identified by UNHCR estimates and other agencies. Most refugees are eventually returned to their home countries or integrated into the places they first seek asylum, options that are out of the question for many LGBTI refugees in Africa.

The ponderous refugee bureaucracy can lead even those who understand how to access the system to fall through the cracks. That's what happened to one Ugandan now staying in Nairobi, who asked to be referred to as Mata, after his favorite player on his favorite soccer team, England's Manchester United. Mata and two of his friends were holding a meeting one November morning at the Kampala home of Ugandan LGBTI activist Sam Ganafa when the police came knocking at the gate.

According to Mata's account, the police had Ganafa in handcuffs, and were there to search the house. They marched the group down the road to the police station as onlookers shouted "kisiyaga," a Ugandan epithet for homosexual so painful that Mata couldn't even speak it out loud while recounting his story. During their four days in jail, police paraded them before photographers for the Red Pepper tabloid and TV stations, beating them when they tried to cover their faces. Police stuck their hands down their pants to see if they were wearing diapers (believing anal sex causes incontinence) and forced them to go for a "medical checkup to see [if] our asses have been used."

"These guys are gays," the police warned the other prisoners. "Hide your asses."

After they were released, the trio spent about two months in a safe house arranged by Sexual Minorities Uganda before a local priest raised money from British donors to cover bus tickets to Nairobi. After an overnight journey, they arrived in the city on Tuesday, Jan. 21, with an amount of cash equal to about $100 between the three of them. They immediately took a taxi to the upscale Westlands neighborhood where the priest had told them to register at U.N. headquarters. But when they got there in the evening, they were told they had to first go to an office run by the Kenyan government.

Over the course of the week they bounced between offices trying to register, each time being told they needed to report to a different office. They quickly burned through their savings on cab fair and hotel bills. Mata used his last cash to buy a bus ticket to the seaside town of Melindi for the weekend. He had been flirting over Facebook with a Kenyan man there over the past two years, and he hoped this man would put him up until the refugee offices reopened on Monday and give him some money to tide the trio over until they found a way to support themselves. Mata also hoped they might become boyfriends.

But when the Kenyan learned why he had left Uganda, Mata said, their relationship changed. "He used me," Mata said, forcing him to have rough sex as much as seven times a night. When Mata tried to refuse, the Kenyan man threatened to kick him out. The Kenyan man wouldn't let Mata leave, nor would he give him money to keep his friends from having to sleep on the streets of Nairobi. When he finally let him go at the end of the week, all he gave him was bus fare back to Nairobi.

After this two-week ordeal, they finally found their way to an NGO that processed their cases. (The NGO asked that its name not be used out of concern for the safety of its staff and clients.) The organization rented them an unfurnished house, and provided them with a monthly stipend around $50 per month each, an amount Mata said was later cut in half because of the growing number of LGBTI refugees relying on the organization. Mata got lucky — he was quickly granted refugee status and his application for resettlement is now pending with the Canadian embassy. But in the meantime he lives in hiding to avoid being sent to the refugee camps, and he and his two friends rely on sex work to survive.

He doesn't really care where he goes, he said, as long as it's somewhere "where I'm free to live — where, if I have a boyfriend ... I am free to express myself."

He just wants to get there as soon as possible.

"Kenya is like Uganda," he said.