If you're in the mood for a head-spinning brutal biopic featuring a breakout role for a major talent: Bronson (2009, Nicolas Winding Refn)

It’s a hell of a thing to not know yourself. Nicolas Winding Refn’s propulsive sorta-biopic Bronson gives us the figure of England’s most notorious prisoner, an unrepentant bald-headed bruiser by the name of Charlie Bronson (played in a towering performance by Tom Hardy), shows us what he’s capable of and then dumps him in our lap, unreconstructed and screaming. What could be a straightforward roll in the muck is instead transformed into something lively, jolly, almost joyful; Winding Refn gooses the frankly-dull narrative of Bronson’s rise to prominence (which can be summed up as, “I punched quite a lot of people”) with fourth-wall breaking narration, cutaways to artificial stage-bound performance pieces, blasts of opera and synth-pop on the soundtrack and one incongruously lovely animated interlude, all in the spirit of making this a good time at the cinema. The first line in the film, delivered by Bronson directly to the camera, is, “I always wanted to be famous,” and the idea of uncontrolled violence as a form of aggressive performance art is something that comes up enough within the fabric of the film that it’s easy to see why it’s often bandied about as the film’s main concern. But I’m not convinced. There’s something else here that’s being missed.

If you really examine Bronson, you’ll notice that the brutality in it is never quite explained in a consistent manner; depending on the situation, it can be beautified, macho-ed up, neutered or eroticized in both hetero- and homosexual ways. (One of the most fascinating setpieces in the film is Glass Candy’s insinuating “Digital Versicolor” spreading across a striptease routine witnessed by Bronson and a bare-knuckle boxing match participated in by him – two sides of the same coin, bodies and flesh turned into crude objects for money-making). This level of thematic breakdown in most films would smack of incompetence, but here I see Winding Refn grasping at something larger and more elusive – rather than give us a simple twist on celebrity culture, he’s chosen to show us a man in the process of figuring himself out, terrified that there’s nothing inside and aestheticizing his bad deeds in a hundred different ways to hide the fact that he can’t control and doesn’t understand his own impulses. If we don’t know Bronson by the end of the film, it’s because he doesn’t either. He only knows he’s caged, he’s screaming and he needs to hit something.

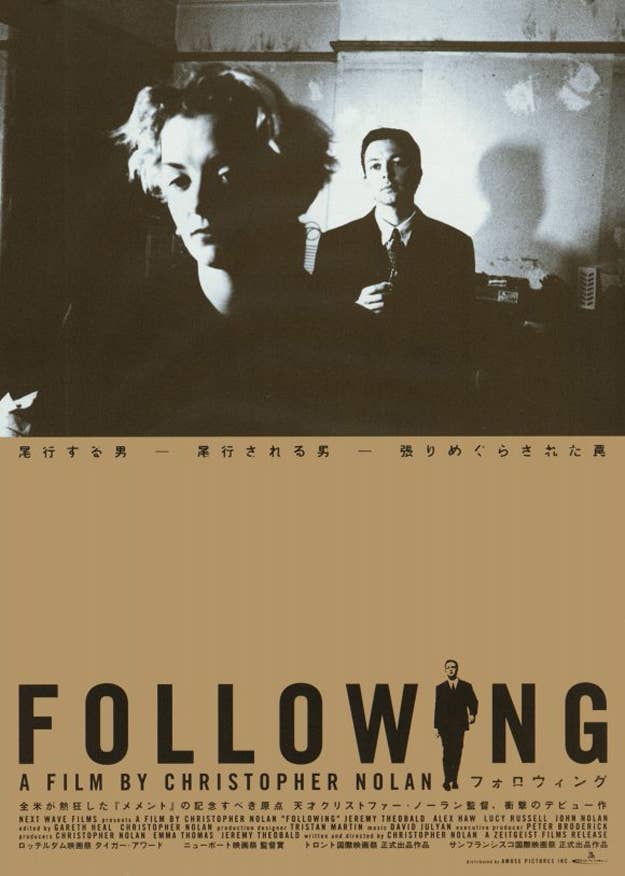

If you're in the mood to see where one of Hollywood's biggest directors got his modest start: Following (1998, Christopher Nolan)

“You can tell a lot about people from their stuff.” So says Cobb (Alex Haw), a dapper-looking thief, to the nameless protagonist (Jeremy Theobald) of Christopher Nolan’s swift, tricky debut film Following. An interest in people is in fact what sets the plot in motion – Theobald, an unemployed would-be writer, takes to randomly following strangers on the street as a way to kill time and, presumably, gather information for any future works. One day, he follows Haw into a café and has his cover blown; instead of being hostile or abusive, Haw decides to teach this aimless young man the ins and outs of breaking and entering. This simple action leads into intrigue involving a mysterious blond woman (Lucy Russell) whose flat was burgled by the two men, a bald crime bigwig she used to date, and a safe full of money. All standard noir tropes, for sure, but the thing about familiar ideas is that it’s in how you use them, and Following has a striking amount of inspiration to go with its more well-worn elements.

It’s a small attention-getter of a work, a labor of love filmed over the course of a year, and it must be said that it looks fantastic for a $6,000 film. Nolan shoots in evocative, jittery black and white (furthering the noir connection) and gets credible performances from his amateur cast. (Haw in particular does very well by the showy monologues his character gets vis-à-vis the art of theft.) But as neat as it looks, Following is foremost a triumph of writing. The script is arranged achronologically, so we’re left to compile the tale together alongside Theobald (a technique Nolan would render to even greater effect in his masterful Memento), yet we’re also occasionally given glimpses of things he couldn’t have known, which turns the tale from just a mere mind game into a ruthless crawl towards oblivion. As the film jumps back and forth in time and certain things get gradually revealed (the origin of the bruises on Theobald’s face, the blond’s debt to the bald man, Haw’s eventual role in the proceedings), it becomes clear that Theobald is careening towards a fate he can’t escape. Nolan’s sharp enough to lay out the themes and conflicts he’ll be dealing with early on and just let the pieces lock into place. Theft, in the words of Cobb, is an offbeat form of helping other people – by removing their possessions, you help them get down to what’s important (“Take it away, show them what they had.”). It’s the crucial difference between having an interest in people and actually knowing something about them.

If you're in the mood for a war film that's about as British as they come: Play Dirty (1969, Andre de Toth)

“Watch, listen and say nothing.” Odd advice to be given during the course of a war movie. But here it is in Andre de Toth’s terrific Play Dirty, and dammit if it isn’t useful advice after all. While Play Dirty nicks its structure from The Dirty Dozen — extraneous officer Captain Douglas (Michael Caine) is recruited to lead a seven-strong gang of ruffians and thugs headed up by Captain Leech (Nigel Davenport) to a Nazi-controlled North African fuel depot with the intention of blowing it to bits — the rhythm is far quieter than that of Robert Aldrich’s iconic bombast. Rather than wall-to-wall action a la the typical Dozen ripoff, the script dredges up tension from long stretches of entropic inaction leavened with personality-clash power struggles — drama derived from human nature instead of threat of immediate death.

But this is a war movie, after all, and what good is a war movie that doesn’t ultimately mine mortality and failure for dramatic thrust? This is where Play Dirty ultimately feels unique: it takes that omnipresent threat of death and stretches it to its breaking point, trading moment-by-moment excitement for slow-boil pacing occasionally punctured by brief spasms of violence. There is, of course, no glory at the end of this road (it’s the late ‘60s, after all), just a chance to walk away from the violence intact, and de Toth gets amazing mileage out of using quiet and agonizingly slow movements to drive home the need to be careful at the cost of life; whether it’s Caine trying to carefully drag three Jeeps up a cliff side, a bomb expert searching ever so delicately for the trigger to an oasis tripwire or the climactic fuel-depot raid under cover of night, de Toth milks every scenario for maximum tension until it’s time to erupt. (For this, he makes particularly good use of sudden zooms – the oasis scene in particular ends with one of the most viscerally potent zoom-ins I’ve ever seen, and the explosion that happens in its aftermath pales in comparison.) If Play Dirty feels slower than its brethren, it’s by design. It is, in essence, a two-hour build to an enormous fire-and-noise catharsis. War isn’t all crusading heroism and Boy’s Own Adventure excitement – sometimes it’s just a long, grueling trek across arid, hostile territory towards certain death.

The Netflix streaming library is vast and daunting and mostly filled with crap. Steve Carlson is the Netflix video clerk, and every week he hand-delivers three awesome movies you've never heard of before. He's been writing about movies in one form or another on the Internet since 2002 and co-hosts the Bad Idea Podcast. Someone once called him the lonely Magellan of exploitation cinema. He thinks that's the best compliment he's ever received.