A dead suburb just east of Phoenix.

It's long after midnight.

I kneel on the sidewalk of an otherwise quiet street and scream into my hands.

I can't see through my tears. Can't breathe.

The blood pours from my mouth, from the bridge of my nose, leaking like syrup onto my hand, through my fingers, and onto the sidewalk.

I check to see if my tooth is loose. I feel my nose to find the broken part, the jutting bone, and feel a pain in my ears when I squeeze it. I hold my hands over my face and try to stand.

Brad is running back from the CVS corner store. I hear the thwack of his Converse soles on the pavement, and even though the streetlamps are mostly out, I can see his silhouette.

He says he got Band-Aids. Rubbing alcohol. Asks if I'm OK.

I nod.

He tells me to tilt my head back and I do it as he walks me back to the store where there's a restroom we can use to clean up. We wait together on the corner for the red hand to turn into the green walking man. Inside CVS, the fluorescent lights are harsh and the familiar Dawson's Creek theme song plays over the loudspeaker as he guides me through the aisles toward the bathroom, opens the door, and closes it behind me. He turns on the dim, yellowed light. I see myself for the first time in the dirty mirror.

My eyes are swollen.

My nose is fat and purple and lacerated.

There are copper bloodstains on my gray shirt.

I don't look like me.

"I'm gonna make you all better," Bradley says, sounding like a little boy. That's how we talk to each other sometimes. Like we're still kids.

"Thank you," I say, and he asks me to sit on the edge of the toilet. He wipes the blood off of me.

"This is gonna hurt, OK?"

I nod and close my eyes. He pours the rubbing alcohol into the white, twist-off cap and slowly pours it onto my cuts.

It burns. I hold his hand tighter. I close my eyes. Clench my teeth.

He wipes down my face and quickly puts a bandage on my nose. And another.

He says, "I love you," and I say, "I know you do."

He says, "I'm sorry I did this to you," and I say, "I know you are."

And then I say, "It's OK, Bradley."

I didn't sleep much the night before, just dozed in and out of half-sleep and worried dreams. I rolled into Brad, the two of us mummy-wrapped in our sleeping bag, a messy mop of hair in his face. I rubbed my finger along the scars on the underside of his forearm, still infected and blackened from all the times the needle missed his veins. My uncle had scars like that; they found him dead at 38 in the same bed he slept in as a child. Brad looks a little like my uncle: boyish and handsome, blue-eyed with dark hair that turns blondish in the sun. He was sleeping with his mouth open, drool on his pillow. I kissed his warm cheek, his warm mouth, and he tasted like sleep and stale vodka. The taste always reminded me of my mother and those nights she spent in her recliner, asleep or unconscious, the sharp-burn stink of ethanol snoring out of her gaping mouth — I would kiss her just like this.

I woke on the floor of the garage where Brad and I had been living, opening my eyes to soft daylight that rivered beneath the pull-down door. Muted engine hums announced neighbors leaving for work.

When Brad woke up, he wanted pancakes, and I asked him which kind, and he said, "Blueberry, of course," and folded his arms in the fussy huff of a little boy. I asked him if he remembered that time we went for pancakes in New York, and he said, "Don't remind me."

That was the night we lost my car, the one that belonged to my father before he died. We had stopped for pancakes at one of those New York diners, the kind with glass display cases full of giant cake slices and booths shaped like half-moons. Afterward, we rushed through the bitter cold bundled in layers, our sweaters pulled over our wind-smacked faces, our heads burrowed down, a left onto 10th Avenue — and my father's Ford Taurus wasn't there where we'd left it.

We asked a cop on a horse if he had seen a rust-colored Taurus and he shrugged, sending us to the tow yard along the West Side Highway, an hour's walk. We huddled together, Brad's hands inside my pockets, the city looming along the Hudson. I couldn't speak, except to blurt a chattery, "Fuck, it's cold!" every few minutes, and Brad would nod his head. When the wind subsided, our conversation inevitably turned to shrinkage. Ten bucks, he bet me, that his dick and balls had shriveled much smaller than mine. I didn't take the bet, mostly because I knew he didn't have $10 to his name.

No sign of the car at the tow yard, and we walked our defeated, sulking bodies back through razor-blade winds, hours passing upon hours, the two of us lost and still looking, telling each other stories until the earliest traces of daybreak, the pink and pale sky bleeding through the blackness of night. He knew the car held a certain sentimental significance for me, the last physical thing I had of my father, and he promised me we'd find it — but we never did. And for some reason it didn't seem to matter to me. Nothing seemed to matter, as long as we were together.

Now, Brad casted aside the Styrofoam box of half-eaten pancakes, and I reminded him he had rehab at 3 p.m. at the hospital up the road. But I'll be back before then, I said, just have to run to the library and use the internet. I asked him if he had any cash for the bus. He said no. I grabbed his backpack and unzipped the top layer.

"I said no!"

"I'm just checking."

"Put my shit down," he said.

"Why?"

"Because it's mine," he said, and tried to snag his backpack away.

I unzipped the lower compartment.

Burnt straws, a warped, blackened spoon, and a couple of used needles. I held the needle up to show him.

"Fuck you," he said.

"No, fuck you."

"Put my shit down," he said again.

I did. Then I saw his sneaker lying on the ground. He saw it too and we both darted for it, grabbed it, struggled over it. I managed to rip the Velcro open to dig into the secret pocket in the shoe's tongue, and I pulled out a small Baggie of brown powder.

"I swear to God, you better give me my shit," he said, staring at me with vacant, hateful eyes.

He tackled me into the wall. I shoved him off, ran into our small bathroom, and flushed the Baggie down the toilet. He pushed me hard into the tub and I hit my head with a hollow thud against the tile wall.

"You're fucking crazy!"

"I'll never forgive you for that," he said. He told me he doesn't love me anymore, that he's been fucking that Australian guy from his rehab. And Tim, the Starbucks barista. He fucked him too.

I didn't understand.

"Actually, he fucked me," he said with a smirk.

I tackled him into a table. He shoved me into a mirror that shattered around us.

There was blood but I couldn't tell if it was mine or his. He pushed me backward and grabbed a pair of scissors. He lunged and swiped at my face. I knocked the scissors from his hands but he pulled my shirt over my head. I couldn't see through the cotton and polyester of my shirt, but I smelled fire.

And then I felt it. The sharp, numbing burn icy on my skin. I pulled the shirt

off over my head, rushed into the kitchen sink and turned on the water.

Brad locked himself in the bathroom. I banged on the door with my first. The red, bloody print of my fist smeared against the white door.

"Let me in!"

"I'm calling the police!" he yelled through the door.

"You just set me on fire and you're calling the cops?"

I heard him say our address. He was polite on the phone. Yes, thank you very much. Please hurry.

The cops arrived a few minutes later, tackled me to the ground, cuffed my hands behind my back, and threatened to arrest me. Strobing police lights and the crackle of a police radio. I lay with my face against the sidewalk, the metal from the handcuffs digging into my wrists.

And I closed my eyes to a memory: my father handcuffed just like me, on our front porch, while the police questioned my mother. He had flushed her vodka down the toilet. I saw his face pressed against the window of the cop car with that look that said, I can't live like this anymore.

I heard my name, and the officer who stood over me asked me to stand. I struggled to my feet as tears streamed down my face. She said they spoke to a neighbor who saw the fight and he was corroborating my story. They unlocked my handcuffs to look at my hands.

"No marks on his knuckles," she said.

They didn't arrest me, but warned me they would if they had to come back.

That night, I asked Bradley to stay. He promised he would.

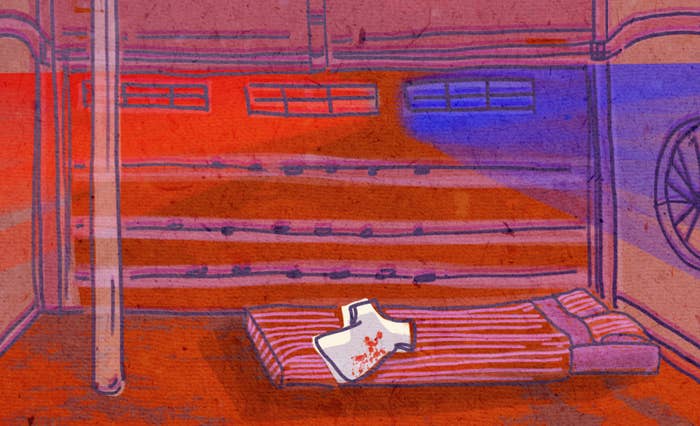

But I woke up alone in the cold, concrete garage we shared — where we had spent so many nights, watching movies on a shattered computer screen, whispering promises to each other before we'd fall asleep. He was gone, a quiet escape, an early morning bus to Fort Worth.

Two days later, I sit in some shithole diner with a tepid cup of coffee in front of me. You are nothing, I tell myself. And when I think of everything I don't have, everything I've lost, I want to beg him to come back. Because nothing else matters as long as I have him. It doesn't matter if I'm sleeping in a garage with no money and no clothes. It was the happiest I had ever been.

I think of something my mother said to me the last time I saw her. I was too skinny and too pale, mustard- and purple-hued sleepless bags beneath my eyes, looking older and too tired and too weary for 22, and she said, "What's going on with you? You're acting like a drug addict." I had some quip in response, something like, "You would know all about that" — because her sister was one, and her other sister too, and her brother. But I wasn't one. Not like they were.

My denial makes me laugh quietly at first, and then more loudly. She was right, I think. I am an addict. I say it out loud, about myself. I had avoided booze and pills and powders and needles my entire life, and here I was, a lifetime spent sober, and still, the gaunt face and tired eyes and poisoned brain and blindness of a real junkie. I sip my coffee and remember the way my uncle used to talk about being in love with heroin. Not addicted to it — in love with it. That's what it felt like to him. It felt like love. And wanting to hold Brad one more time was no different than my uncle needing that one more fix, or my mother needing that one more drink. I had spent my entire life running from addiction, and all this time, I had been running straight toward it, right into its arms, and I didn't want it to ever let me go.

My phone vibrates and stutters on the table. On the shattered screen of my flip phone, a text message from Brad:

"So, that's it? We're done?"

I need him.

To hold him.

Just one more time.

Just once more, and then I could say good-bye.

"Yes," I write. "We're done."

Kenny Porpora is the author of The Autumn Balloon (Grand Central Publishing, 2015).