PARK CITY, Utah — As a Sundance Film Festival newbie, the most striking thing to me so far — especially as someone who covers Black Hollywood — is that this year's lineup offers a series of films that capture landmark black experiences and is serving them to a predominantly white audience.

These films speak directly to the lives of my fellow tribe members today and to the struggles that our parents and grandparents fought so hard to live through and overcome. It's important for nonbrown viewers to witness the heartbreaking civil rights battles of singer Nina Simone, or the contemporary reality of being killed for being a black teen who blared loud music at a gas station, or the affecting footage of the valiant rise and heartbreaking fall of the Black Panther Party, all the more poignant considering its biggest supporters included a largely nonblack base.

That film — The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution — is excellent. It's the latest from director Stanley Nelson, who came to the festival in 2010 to premiere Freedom Riders, a moving documentary that highlighted the story behind the hundreds of civil rights activists who faced down segregation. In Nelson's latest film, the women's voices are as vital and important as those of their male counterparts, something not often seen in documentaries about times of social change. The fact that these women aren't tied to their husbands or lovers, but are seen as entities of their own, makes The Black Panthers all the more exceptional.

I was practically still shaking the morning after viewing the documentary, overwhelmed by the idea that young people were able to assemble and create an organization that caused high-ranking government officials to tremble and respond in — at times — violent ways.

Nelson, who is known for exploring African-American experiences in telling documentaries, is a smart man, and he's making strategic decisions in presenting The Black Panthers. This documentary will open the Pan African Film Festival in Los Angeles after it leaves Sundance, the former festival being a space where such a film seems meant to have its first viewing. After its festival run, Nelson plans for the film to have a limited theatrical release at some point, before landing on PBS in February 2016.

Coming to the Sundance Film Festival first — an event where you can almost count the number of black participants on one hand — was the bold choice, and one with a greater meaning: The real goal here is to have as many people see a film like this as possible — black, white, or otherwise.

"About six weeks ago, we brought some activists together at the Ford Foundation and had them look at the film and said, 'What do you think? Is this a film you can use? Or is it something that's a little bit too scary?' All of them said they see this as a film about young people realizing the power that they had," Nelson said in a Q&A after his documentary premiered to a packed house on Jan. 23. "It was very clear it didn't work for the Panthers, and there were mistakes made. What's going on in this country is amazing. It could be the start of some real change. I think that hopefully we can get this film out to people and more and more people can use it. That's our hope."

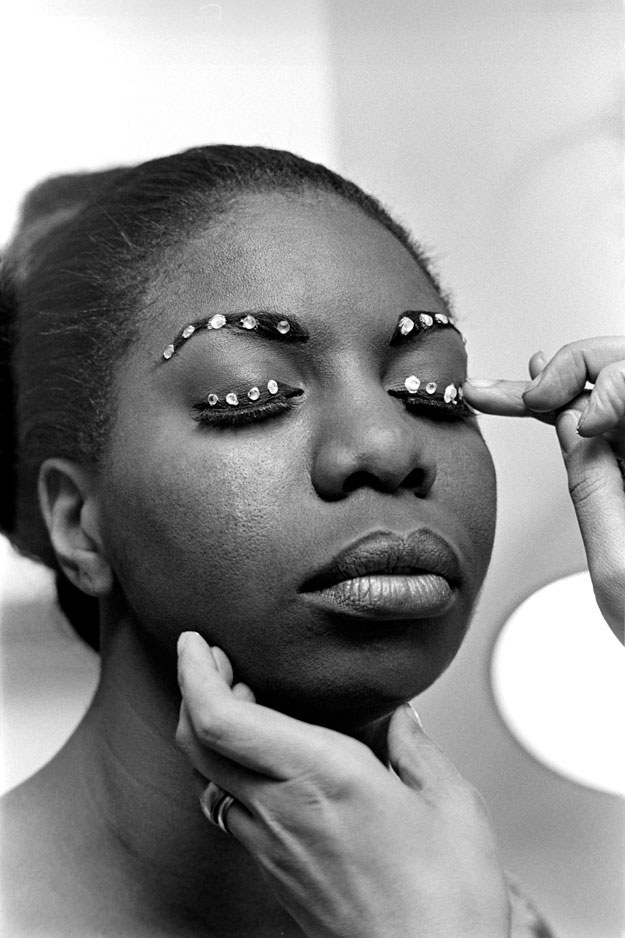

Sparking activism is especially important at Sundance, and it's a theme that seemed prevalent overall this year. What Happened, Miss Simone?, the gripping Nina Simone documentary, does a deep dive into how the jazz singer and classically trained pianist sacrificed her successful career after getting politically involved with what was happening in 1960s America and creating music that spoke to, inspired, and provided the soundtrack for a movement.

"I could sing to help my people," says Simone in the documentary, "and that became the mainstay of my life."

Simone's misstep was that she took it too far, and her black nationalist leanings couldn't sustain the mainstream audience she'd garnered earlier in her career. One of the more haunting moments of the film — especially considering the news narrative throughout 2014 — is when Simone said in a television interview at the tail end of her life that her music was no longer relevant. "There is no more civil rights," she said emphatically. It's a quote that lingered in my mind for days after the screening and seemed to sink in with much of the largely white audience — heads other than mine were nodding at the stark mention. All of us, it seemed, understood how important that scene was and how much it was saying about where we are today, in an era when a #BlackLivesMatter message still seems necessary.

For the film's director, Liz Garbus, it was the saddest moment in a documentary filled with sorrow and loss.

"If we had voices like Nina Simone's today, speaking the pain and the passion of the movement that's been building, I think, on the streets in the past six months," she said following the screening, "I think we can all see the place of these songs today."

Garbus' words helped to introduce John Legend, who recently won a Golden Globe for his original song (with rapper Common) "Glory," which was written for Ava DuVernay's Selma, another film whose subject matter collides head-on with social change and a harrowing racial climate. Legend performed Simone hits, telling the audience how she inspired him as a musician and as an activist.

"I'm so grateful to be here today honoring the legacy of the wonderful, powerful, dynamic, super-talented Nina Simone," said Legend, who also is up for an Oscar for "Glory." "I find myself studying her versions of all kinds of songs, thinking about her words, thinking about her boldness, thinking about her commitment to justice. I'm truly humbled to be here tonight to honor her legacy."

When profound moments like that happen, it's often comforting to be surrounded by people who look like you. Many of us have felt a significant amount of vulnerability while taking in recent news headlines, transfixed in horror by the killing of young black boys for being young black boys. The slayings of Trayvon Martin, Jordan Davis (3 ½ Minutes, a documentary about his killing, is also premiering at Sundance), Mike Brown, and so many others have inspired thousands to march for social justice. In New York, I witnessed firsthand (and remember being taken aback by) the high number of nonblack protesters who created poster boards and bundled their children up and set out to walk alongside black people to take a stand. Their spiritual forebears are glimpsed in the Simone documentary as well — one march features black men wearing "I Am a Man" placards — but in far fewer number.

Only in watching Nelson's Black Panthers documentary was I able to shift gears, to consider the brilliance in bringing films that are specifically black to Sundance's overwhelmingly white audience, in dropping narrative bombs in a space that seems safe and dove-white, reflective of the white privilege of most filmmakers and their audiences.

The Black Panthers are most often called a group that was antiwhite, when, in actuality, they were antiestablishment. They were against a society that disenfranchised people based on the color of their skin and their socioeconomic status. In later years, before the subsequent split of the organization, emerging leaders like the charismatic Fred Hampton — who was killed by police in an FBI-orchestrated raid — were able to align the group with Latino leaders and other leaders who represented poor whites to join forces in the name of social change. Such cooperation represented a scary threat to a J. Edgar Hoover–led FBI.

"One of the things happening in this country with the police and what's happening in black communities right now is that people, young and old, white and black, everybody is seeing there's a real problem, and there's really a need for change," said Nelson during the post-screening Q&A. "We really want people to push for change."

The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution gut-punches you in the right way and connects the dots with what's happening in 2015. Some might consider seeing it to be life-changing; I did, because it's the kind of documentary that inspires you to read more, become introspective, and realize the power of a few strong voices, something we continually take for granted as a collective society.

I have no illusion that the Sundance Film Festival will become a beacon of blackness overnight. That's simply not the intention of this mainstream festival — what it does best is highlight emerging filmmakers, some of whom have the potential to tell stories that spark sweeping social change. It's a place that celebrates an art form with the ability to capture the totality of human experience and puts it before an audience that may very well never encounter strife of any sort.

So why not bring black stories to a white audience? When watching Nelson's doc, I sat next to a white woman who was a high school student in South New Jersey in the late 1960s, and was curious to learn more about a group she saw active in neighboring Philadelphia. On the other side of me sat her son, a young filmmaker who is a fan of Nelson's 2010 doc and is working on a documentary about Judge Damon Keith of Detroit, my hometown. Keith is a Detroit staple, a ninetysomething black man who is still a sitting judge.

They were right there with me as I laughed, clapped, and fought tears through the 114-minute viewing, jam-packed with what I'd guess was the festival's most diverse audience. (Which, even still, was starkly white.) And I'd venture to guess that they too resisted the urge to raise their fists in the air and cry out, "Power to the people!": a collective fraternal exclamation that many people — people of all colors, as Stanley's doc will show — once did in a show of solidarity.

A previous version of this article misstated "What Happened, Miss Simone?" director Liz Garbus' last name. It has since been corrected.