SIERRA MAESTRA, Cuba – “For the moment, Cuba is still Cuba, but in a few years the culture will be gone.” Frans Smans, a tourist from Holland, sat under the shade of a simple corrugated metal roof, taking in the view of the Sierra Maestra mountains in the east of the country.

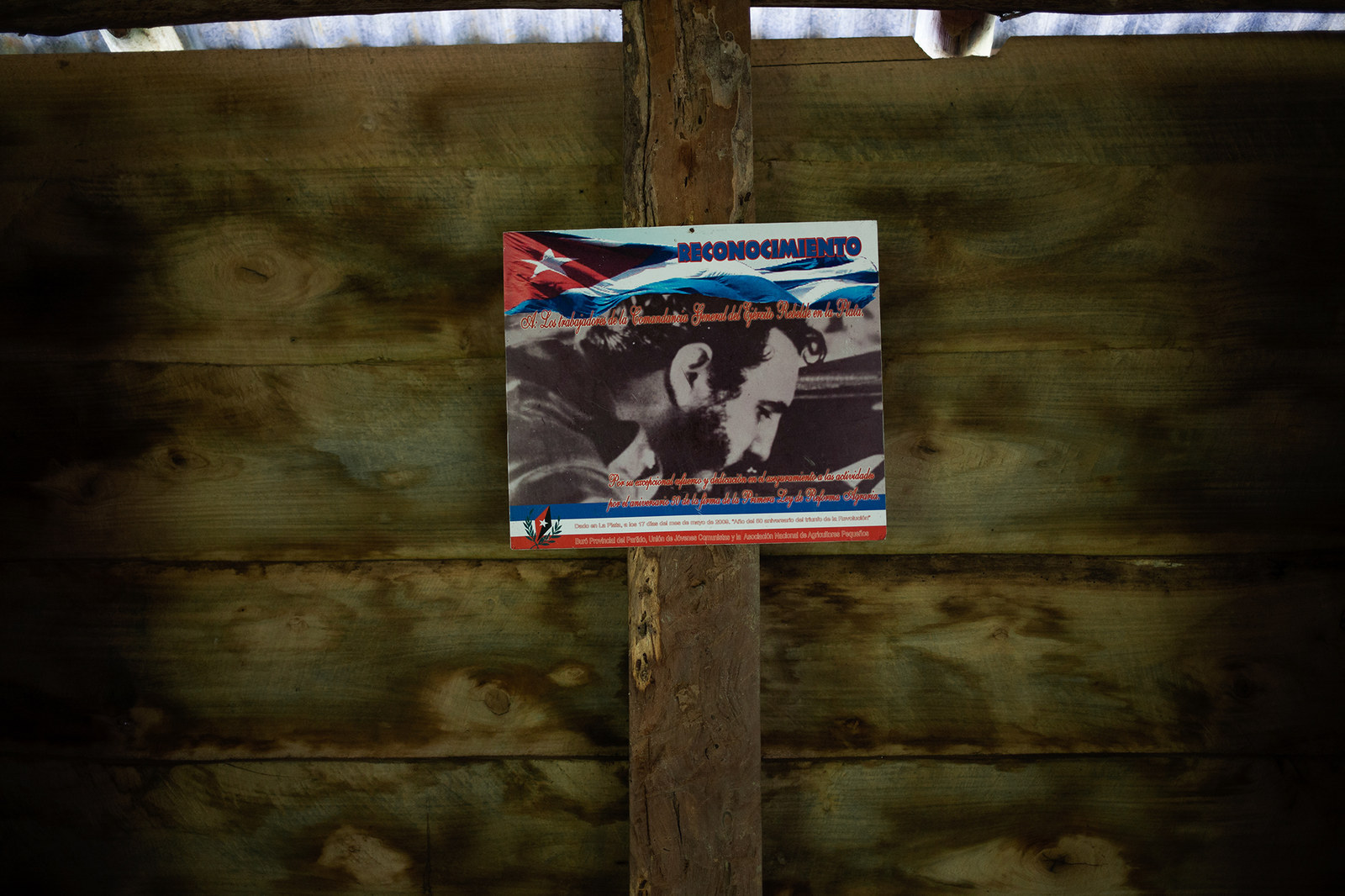

Smans, a 63-year-old project manager, was part of a group of two dozen Dutch tourists who had trekked their way up through the tropical forest to visit Comandancia de la Plata, the command center from which Fidel Castro orchestrated the revolution that saw him sweep to power in 1959. The huts are spread out over a moderately steep hilltop. Beginning at the Medina Family house, where a quintet that entertained guerrilla fighters during the revolution lived, visitors trek up to the Press bungalow, onto Fidel’s thatch-roofed house and into Radio Rebelde, from where revolutionary fighters broadcast their news to the country.

The European’s lament is typical of many visitors to Cuba’s tourist spots these days. The recent softening of diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Cuba is expected to bring an avalanche of American visitors, and it has got some European tourists all worked up. “Larger numbers of people from other countries are now trying to get to Cuba before Miami Spring Breakers enter the country,” said Alana Tummino, policy director at the New York-based Americas Society-Council of the Americas.

But while Europeans might be a little hysterical about the potential increase in American visitors, for many Cubans it’s a very welcome change. All across the island, people are revamping their apartments to rent out rooms and opening small restaurants to accommodate this impending tourism boom. “This is business,” said Julio Cesar Castillo, who is building two additional rooms to rent out to foreigners.

Despite what some Americans might think, Cuba isn’t a Caribbean island version of North Korea, closed off to the world — it already relies heavily on tourism. Last year, tourism and its wider effects accounted for 10.4% of Cuba's GDP and generated 124,500 jobs, according to a report by the World Travel and Tourism Council. And tourism has increased by more than 20% in the last year: approximately 237,200 tourists arrived in May this year, compared to 195,900 during the same month last year. Of these, visitors from Canada, England, Germany, and France accounted for nearly half.

A limited number of Americans already visit Cuba, and the number is expected to bloom. Between January and May, 51,458 U.S. citizens visited Cuba, up from 37,459 over the same period last year, according to the Associated Press. Some of these came clandestinely, flying through Mexico or Panama, but many entered the country through legal loopholes: as part of "people to people" tours, to conduct research or for Cuban-Americans to visit family.

The Cuban government is keen to keep tight control on the message put out about tourism to the island — BuzzFeed was accompanied by a government minder during a visit to the Sierra Maestra last month.

But it’s European tourists who have made up the vast majority of visitors for decades. Luis Angel Segura, a caretaker at the Comandancia, estimated that some 10,000 people visit the site every year. “Tourism has advantages and disadvantages but it does bring fresh capital,” said Segura. At Villa Santo Domingo hotel’s reception, where Celine Dion’s My Heart Will Go On is playing softly in the background, there are two clocks on the wall: one with the local time and another with Germany’s.

Down the road from the hotel, a sign at the single-floor preschool and elementary school greets visitors: “Welcome to Juan Dominguez Primary School.” Santo Domingo is difficult to reach, especially with public transportation: from Santiago de Cuba, it is a five hour car ride on winding, poorly maintained roads.

Bilingual signs are etched above all classroom doors, too, so that large French and Italian tour groups can understand, said Miguel Delgado Rubio, the school director. The visits have become so frequent that the 54 young students here “don’t get distracted, they’ve become accustomed to it,” he added. Santo Domingo is small and visitors walk the main street after their morning trek to the Comandancia to get a sense of town life. Roosters and pigs cross the narrow highway nonchalantly while barefoot campesinos ride casually along it on horses. There is still no Wifi there or a proper hospital. Like much else on the island, Santo Domingo seems partially frozen in time.

What’s more, most Cubans embrace the tourists walking around in a curious daze, and the ones that are likely to come in the future: Americans. “The children think that the closer relations [with the U.S] are good,” said Rubio. “Things will cost less to import,” he added. To prepare for this likely influx, the school hired an English teacher in September.

Down the street, at the tiny library in town, Mislania Viltres Rosales, who oversees the children’s section, said she wants to learn English, too. As she walks around showing off books by Mark Twain and Cuban national hero José Martí, she said it was time for Americans “see the humanity of our country, that we are all united.”

But beneath the surface here — and in towns and cities across the island — lies quiet suspicion tinged with fear. Every neighborhood has a spy network called Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, or CDR, intended to monitor any potential subversive activity.

The repercussions of this are extensive and often severe. Last week, around 100 peaceful activists were detained, prompting the U.S. State Department to voice its concern. Cuban authorities regularly detain dissidents; freedom groups rank Cuba among the worst in terms of press censorship and freedom of speech. When asked about the minder who accompanied BuzzFeed, one staffer at Havana’s International Press Center explained that “this is how things work here.”

Another way things work here? Slowly. Segura, the Comandancia caretaker and state-assigned guide for BuzzFeed News, said he had a plan to design Castro- and revolution-related souvenirs like caps and necklaces in time for the wave of American tourists — but it has yet to be approved by local authorities.

It’s not just the business potential of a surge in tourism that interests Segura. He is fascinated by the outside world, in particular with technological advances. Still, he had mixed feelings about increased tourism. “We have to take care of ourselves in terms of drugs and negative influences,” he said, adding that “it is hard to assimilate changes.” But he thinks that the kind of tourists that will be drawn to the Sierra Maestra will not be the rowdy type.

“Those who want beach and sun will go to Varadero ... the ones that will come here are those who want to see how a gigantic man defeated the most advanced army at the time,” said Segura.

But even Americans are weary of Americans.

A family of three from California recently made its way up the hill to the Comandancia. They said they could not travel to Cuba legally — visiting the island for tourism is still banned — so they flew through Panama and asked immigration authorities in Cuba not to stamp their passport.

“You didn’t talk to us,” said the mother, requested anonymity. She said she had wanted to bring her children to the island “before Cuba opens up.”