What if you didn't have to pay for your data plan? What if the biggest data hogs on your phone — your music apps, your streaming video apps — didn't count toward your monthly limit?

It's an intoxicating pitch, and one you'll hear soon. The country's largest data providers are mulling it; their partners are figuring out how to make it work; the FCC, which is in charge of identifying downsides and regulating such things, just lost much of its ability to do so. Caught at the whirling nexus of theory and regulation and commerce, the average internet user's fate is uncertain. But today, a new and unexpected possibility has made itself clear: We may be entering the era of sponsored data — the era of an internet that we don't directly pay for, but that we also don't control. It's the old net neutrality nightmare, in other words, disguised as a gift.

Today, vital portions of the FCC's Open Internet rules were struck down in federal court. These rules, put in place in 2010, were designed to preserve what advocates call net neutrality — an assurance that internet providers can't favor one kind of traffic over another, or charge for access to certain parts of the internet. All traffic, according to the rules, was to be treated equally. Verizon challenged these rules, and mostly won.

This comes just a few weeks after the new chairman of the FCC, Tom Wheeler, a former lobbyist for the telecom industry, startled net neutrality advocates with this quote, given during a Q&A following his first formal public address:

I think we're also going to see a two-sided market where Netflix might say, 'Well, I'll pay in order to make sure that you might receive, my subscriber might receive, the best possible transmission of this movie.' I think we want to let those kinds of things evolve.

Those comments were made with today's decision looming in the distance. "We are concerned about the two-sided market," pro-net-neutrality group Free Press told BuzzFeed at the time. Brent Skorup of the libertarian Mercatus Center at George Mason University, representing the other side of the issue, said that Wheeler was "a little more industry friendly" than his predecessor.

After today's ruling, the Mozilla Foundation issued a strong rebuke: "The D.C. Circuit's decision is alarming for all Internet users." Free Press splashed its website with this graphic:

"This ruling means there is no one who can protect us from ISPs that block or discriminate against websites, applications or services," says a statement from the organization. Tell the FCC to start treating broadband like a communications service, and to restore its Net Neutrality rules."

By "treating broadband like a communications service," Free Press is suggesting categorizing internet providers as "common carriers," like phone companies, a possibility that, in comparison to preserving 2010's stricken FCC rules, is seen by insiders as a long shot. "From a legal perspective, it's easier," Harold Feld, a senior vice president at Public Knowledge, told BuzzFeed. "What makes it difficult is the politics."

"Pretty much everybody in the industry pushed back very hard against it," he said. "There were a lot of people who came around to network neutrality — a reason why these rules were compromised, and had industry buy-in, was that a lot of people in the industry preferred these rules to reclassification." This is a potentially crippling defeat for net neutrality advocates. Trying to reclassify ISPs as utilities, essentially, would give anti-regulation opponents a much clearer position. Wayne Crews of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, which opposes net neutrality, declared victory in a statement, saying the cause is "dead and buried."

"Onward to Internet 3.0 and beyond," the statement says.

The FCC chairman's own statement, while suggesting he is weighing an appeal, was cold comfort to his predecessor's allies. "I am committed to maintaining our networks as engines for economic growth, test beds for innovative services and products, and channels for all forms of speech protected by the First Amendment."

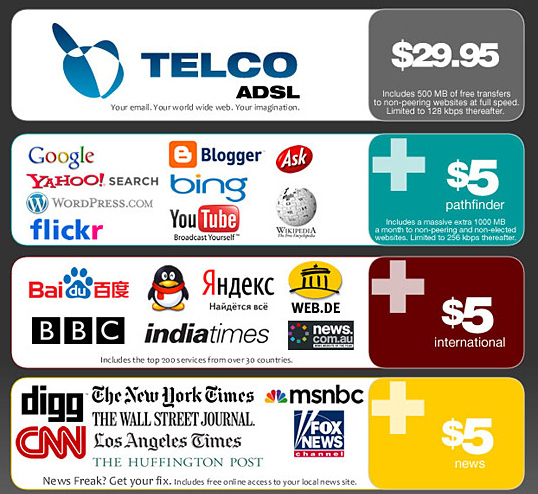

For years, the net neutrality nightmare scenario was as follows: Carriers, such as Comcast, could charge different amounts for access to different tiers of the internet. The basic tier might include email and basic browsing; the next could include Facebook and Twitter; the final tier could include Netflix, YouTube, or Spotify. These tiers would be divided not by bandwidth or speed requirements, but by content type. The internet would become a club with various VIP sections, arbitrarily laid out to benefit internet providers.

This was the vision that propelled net neutrality into the public consciousness, and that led to its inclusion in Barack Obama's 2008 platform. Since then, the nightmare scenario has evolved, with the help of wireless providers. It became more subtle but no less insidious to net neutrality advocates; rather than charging users more for access to different parts of the internet, carriers would charge content providers to make sure their content worked well. The fears changed: Now it wasn't just users that were at risk, but upstart companies. Facebook might be able to afford preferential treatment. But what about the startup that wants to replace Facebook? This is the kind of behavior that Verizon, and others, won the right to engage in today, and it's more likely than ever to come to pass. "We're going to see more pushing of the envelope," Feld says. "Look, you know, Verizon said that if it weren't for these rules, we'd be out negotiating all kinds of deals for [preferential] access." In a statement today, Verizon assured customers that it wouldn't block content, but left open the possibility of preferential access on the service side.

In the last year, a third, equally insidious but even more subtle scenario has emerged, and today became a much realer possibility. On a less regulated internet, content providers — websites and services — might be able to pay for their users' data. Here's how AT&T describes its "Sponsored Data" plans:

Similar to 1-800 phone numbers or free shipping for internet commerce, AT&T's new 'Sponsored Data' service opens up new data use options for AT&T wireless customers and customer-friendly mobile broadband channels to businesses that choose to participate as sponsors…

With the new Sponsored Data service, data charges resulting from eligible uses will be billed directly to the sponsoring company; the customer simply enjoys their content via AT&T's wireless data network. Customers will see the service offered as AT&T Sponsored Data, and the usage will appear on their monthly invoice as Sponsored Data.

If you wanted to access the internet 15 years ago, you would sign up for a service plan with a company like AOL. For a fee — maybe $20, $30, $40 — you would get as much monthly access as you could use, more or less. Five years later, you would have made a similar arrangement with your cable or phone company for broadband access. Five years after that, you would still have a broadband connection, but you could also enter a new contract, this time with your cell phone company: For a monthly fee, you would get access to the entire internet from your smartphone. Your service might be tiered by speed or data allowances, but it has always been a pure pipe to the internet. How you use your bits has been up to you.

Sponsored data attacks the only major unappealing part of this long-standing tradition: its cost. It proposes the possibility that video sites, music sites, and social networking sites could pay for their users' access. It also poses a more fundamental question: If all your favorite services didn't count toward your phone's data plan, why would you bother having a data plan at all?

Recasting internet access as a subsidiary of internet services is not a familiar idea, but it's arriving in many forms. In fact, in the developing world, Facebook has been operating such a service for some time. Facebook for Every Phone, through deals with carriers, provides access to basic Facebook services and apps for free. Facebook isn't just subsidizing some internet experiences, here — it's subsidizing users' very first internet experiences. "It's like the early days of broadcast television," Feld says, "where you would pay affiliates to carry your programming."

The appeal of such an arrangement to a regular customer is obvious: you would pay less for your data, at least directly. "Consumers don't like it when you take things away," says Feld, so "carriers need to be more subtle than that." They will do so primarily, he says, by creating "artificial scarcity" — data caps — and requiring customers, or now, internet companies, to buy their way around them.

The appeal of the latter arrangement to the internet's largest companies is even more obvious: It would give them unprecedented control over the internet and its users. If, in this future, you're choosing between two streaming music services, and one of them pays for your data, there's a very good chance you're going to pick that one.

But which one would be able to do that? The largest one, the incumbent. "This will have profound implications for the internet's ecology," says Feld. Worse, he worries, companies that were willing to fight for net neutrality in the old days won't be such strong allies in 2014, now that they are the largest incumbents on the internet. "They're big, and they can negotiate," he says. "Once you're on the inside, exclusion doesn't seem like such a bad thing. If you're Google, maybe getting access for YouTube is what you want, rather than what you want to fight."