The New York Times was the target of a months-long hacking campaign, originating in China, according to the paper. Its report gives a tick-tock account of what happened: The Chinese government warned that a Times investigation of its prime minister's relatives would "have consequences"; AT&T warned the Times about suspicious network activity; the company, with a security contracter, helped track the hackers as they "moved around [the Times'] systems."

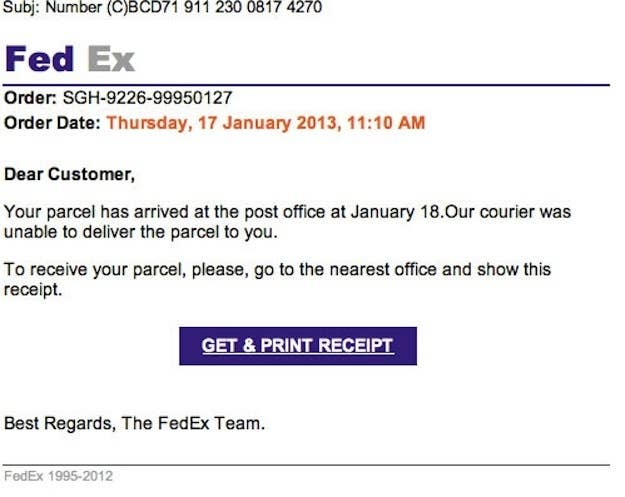

But the most fascinating detail is buried in the 25th paragraph: "[Investigators] suspect the hackers used a so-called spear-phishing attack, in which they send e-mails to employees that contain malicious links or attachments." What these hackers did, in other words, was a finely tailored version of this:

It's handy reminder, just two months after the director of the CIA was felled by lazily hidden Gmail exchanges, that in 2013, "hacking" is as much about people as it is about code.

This wasn't a control room full of masked marauders launching software attacks against a major computer network; it was a group of hackers trying to social-engineer their way into newspaper employees' inboxes. The Times was hacked only after its employees were tricked — its biggest vulnerability, like any other large organization's, wasn't in its software or infrastructure, but in its humans.

A New York Times spear-phishing email could have masqueraded as an internal document, an update to a health-care plan, or a message from the payroll department. Phishing attacks are effective when they're targeted poorly; when a user's name and personal information is incorporated, they're the most powerful tool a hacker could wish for.

It follows that the only way to prevent something like this from happening again is to fix the human factor. In an internal email sent by Arthur Sulzberger Jr. and Mark Thompson, employees were told to to "stay aware and attentive," to "keep your personal information personal," and to "be aware of what you post online."

"The more information you provide," the email reads, "the easier you make it for someone to impersonate you or to steal your identity." Times spokesperson Eileen Murphy adds that Times employees were asked to change their passwords, which is echoed in the memo: "You may recall that within the last few weeks you were asked to change your log-in password." That, it turns out, was while the hack was still developing.

The full memo to employees is below:

Dear Colleagues,

This evening we published an article by Nicole Perlroth regarding a cyber-attack on The New York Times. As this attack was designed to both interfere with our journalism and undermine our reporting we felt an obligation to be transparent about it.

The details of the attack, to the degree that we were able to discuss them publicly, are outlined in the story. We did believe it was important, however, to let you know that we have taken all of the appropriate measures across the company to protect our passwords, systems, content and proprietary information.

As the story noted, the attackers appeared to be targeting newsroom communications. While some business-side computers were affected, confidential employee and customer data were not targeted and the systems housing this data were not breached.

During the period after our systems were hacked, our security experts monitored the activity to make sure the intruders were not accessing sensitive or confidential information, and to make sure we understood what they were doing so we could take all of the appropriate measures to expel them and keep them out. You may recall that within the last few weeks you were asked to change your log-in password. That was just one of the many steps that we took to ensure the security of our systems.

Because we anticipate that this type of activity is likely to continue, we would like to remind you of some of the steps you can take to help protect our company data, as well as your own personal information on whatever device you use. These points are outlined below.

In general, we ask that you stay aware and attentive. If you have any concerns or questions regarding security awareness or if you notice anything unusual about how your computer is operating, contact ********@nytimes.com.

Arthur and Mark

Cyber Diligence

Work and Personal Computers

· Know and use the privacy settings on your computer and on social networking sites. This is the first step toward defending your information.

· Use strong passwords or a passphrase to ensure complexity. Ideally, you should use different passwords for each account you have. Be sure that if you use one password for everything and it becomes compromised, you change it for every account.

· When possible, use two-step verification for your personal email accounts. Two-step verification adds an additional layer of security using your mobile phone that prevents unauthorized access to your accounts in case someone steals or guesses your password. To find out more about Two-step verification using Gmail, for example, go to the security section of your account settings.

· Keep your personal information personal. Do not e-mail or instant message credit card, account, driver's license or social security card numbers to anyone.

· Be aware of what you post online. The more information you provide, the easier you make it for someone to impersonate you or to steal your identity.

· Protect your hardware by keeping all important software and applications up to date, i.e., operating system, Web browser, antivirus, anti-spyware and firewall settings.

Smartphone

· Use a password or passphrase on your Smartphone to prevent compromising your personal information and identity.

· Never reply to text messages from people you don't know.

· Do not text or instant message credit card, account, driver's license or social security card numbers to anyone.