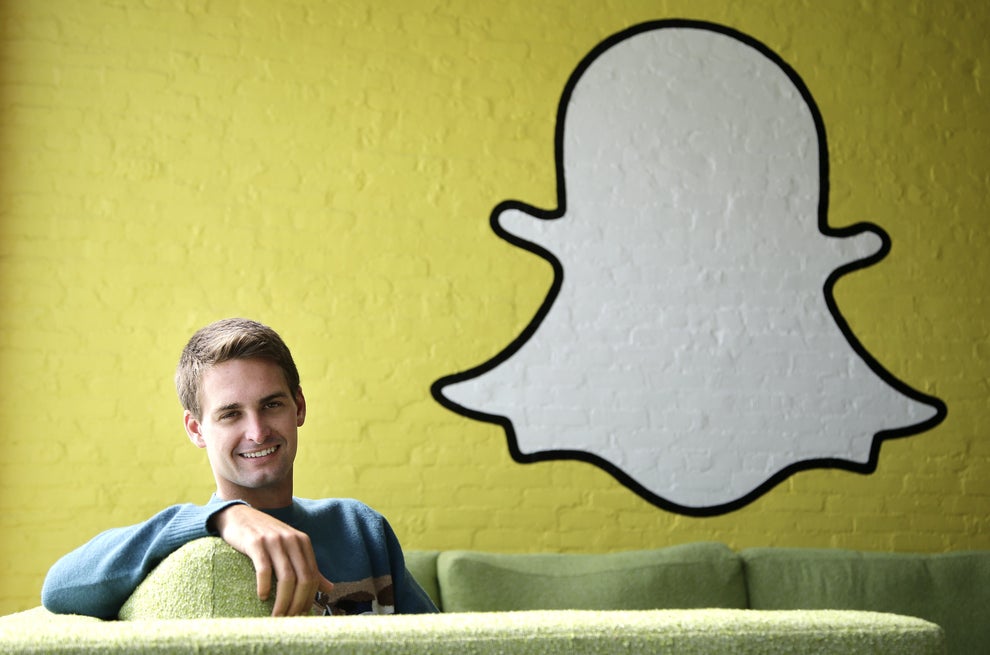

At an industry summit on Friday, Snapchat founder Evan Spiegel delivered a strange and surprising speech. He spoke of the "idea of tying a man to a computer" and quoted Eames. He cast the "traditional social media view of identity" — that "you are the sum of your published experience" — as radical and problematic. He suggested that traditional, profile-based social media was over, because it only made sense in the context of the "binary experience of offline and online." He claimed that the selfie "makes sense as the fundamental unit of communication on Snapchat because it marks the transition between digital media as self-expression and digital media as communication."

Spiegel has been making a public case for the importance of "ephemerality" for some time, and has spoken frequently about his vision for Snapchat, but this talk still clashed with his nascent public persona — the young partier, the brusque founder who turned away Mark Zuckerberg with an email — as well as with the broader public perception of Snapchat. Re/code called it "A Grand Theory of Snapchat, Constructed by Snapchat." Techcrunch said it was a "fascinating keynote speech." The Silicon Valley Business Journal described it as "philosophical."

The talk was all of those things, but it didn't come from nowhere. The pitch Spiegel delivered on Saturday was rooted in the work of a young writer and sociologist — and recent Snapchat hire — named Nathan Jurgenson.

Jurgenson, 31, joined Snapchat last summer. He lives in Brooklyn, far away from Snapchat's Los Angeles headquarters, where working as a "researcher" for Snapchat is one of a handful of gigs — while writing for a variety of publications and serving as a contributing editor at The New Inquiry, he's pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Maryland. His dissertation will focus on "surveillance on social media."

In the tech world, he's best known for articulating and advocating against the concept of "digital dualism." In 2011, Jurgenson planted this flag:

Digital dualists believe that the digital world is "virtual" and the physical world "real." This bias motivates many of the critiques of sites like Facebook and the rest of the social web and I fundamentally think this digital dualism is a fallacy.

The essay found an audience, albeit a small one. "Sociology in America, as a discipline, was slow to address the web," Jurgenson tells BuzzFeed. This, like most of his work, was a sociological essay in both spirit and language.

It also appears to have had a profound influence on Spiegel, who has incorporated its core premise into his vision for the messagine service. Speaking last week, he dismissed the dualists:

Internet Everywhere means that our old conception of the world separated into an online and an offline space is no longer relevant. Traditional social media required that we live experiences in the offline world, record those experiences, and then post them online to recreate the experience and talk about it.

Snapchat initially reached out to Jurgenson, who in February of last year wrote an early appraisal of Snapchat for The New Inquiry. "The tension between experience for its own sake and experience we pursue just to put on Facebook is reaching its breaking point," the piece began. "That breaking point is called Snapchat."

Since joining Snapchat as a researcher, Jurgenson has published three essays, which appear on the company blog between routine housekeeping announcements and product updates. Until recently, those essays seemed to represent the extent of his relationship with Snapchat.

Judging by Snapchat's recent messaging, both in public and to potential investors, it seems as though Jurgenson — or at least his work — has assumed a wider role in defining how Snapchat talks about itself. Spiegel, for example, name-dropped Jurgenson during an interview at Techcrunch's Disrupt conference in September. Since then, his work has been extensively woven into Snapchat's public identity. In an essay published on Jan. 7, Jurgenson wrote:

[Media objects] are the fundamental unit of experience for you to click on, comment on, and share. A photo is posted, and the conversation happens around it, side-by-side, on the screen. Alternatively, one key component of ephemeral social media—appreciated by its users but unexplored in most analyses—is that it rejects this fundamental unit of organization. There are no comments displayed on a Snap, no hearts or likes. With ephemerality, communication is done through photos rather than around them

Contrast that with the notes from Spiegel's talk on Saturday:

[U]ntil now, the photographic process was far too slow for conversation. But with Fast + Easy Media Creation we are able to communicate through photos, not just communicate around them like we did on social media. When we start communicating through media we light up. It's fun.

The selfie makes sense as the fundamental unit of communication on Snapchat because it marks the transition between digital media as self-expression and digital media as communication.

Spiegel, who tells BuzzFeed he wrote his own speech, says he loves to talk to "very smart people" and that Nathan is "one of those people." Jurgenson, who hadn't seen the talk until today, was pleasantly surprised by the extent to which his pet concepts — digital dualism, the "liquid self" — were discussed. "Social media is part of the social world, it doesn't require starting over, intellectually," Jurgenson tells BuzzFeed. "There's mountains of social theory! So that's my mandate, I guess."

"I think it made sense for early social media to fixate on the media object," he says. "It was about creating a second thing — avatar, second life." This thinking, he says, is outmoded: "We need to build a cyberspace. What are our building blocks? That type of thinking, that's how we used desktop computers: to search for media objects."

"When you begin with the smartphone," he says, "searching for information in a database can become secondary to communication."

If the goal in hiring an in-house sociologist was to associate Snapchat with some sort of ideology, there's evidence that it's working. Jurgenson's Snapchat blog post on social networking and ephemerality, published on the Snapchat blog in July, seems to have found traction; just last month, it was thoroughly endorsed in a Wall Street Journal column under the headline, "Do We Want an Erasable Internet?" Writer Farhad Manjoo begins the piece: "This is going to sound silly, but I think Snapchat was the most important technology of 2013."

In the meantime, all eyes are on Venice. Snapchat, which turned down a multi-billion-dollar offer from Facebook and has collected over $120 million in funding, is the poster child for a new generation of messaging apps. Investors and critics alike will naturally hang on Spiegel's every word, but would also do well to pay attention to Jurgenson — the critic, the outsider, the academic, the Brooklynite who's helping write Snapchat's script. "Sociologists are thinking about identity or power or cultural norms in everything we do," Jurgenson says. "Let's think more about culture, about social autonomy, etc. Tech is too important not to."