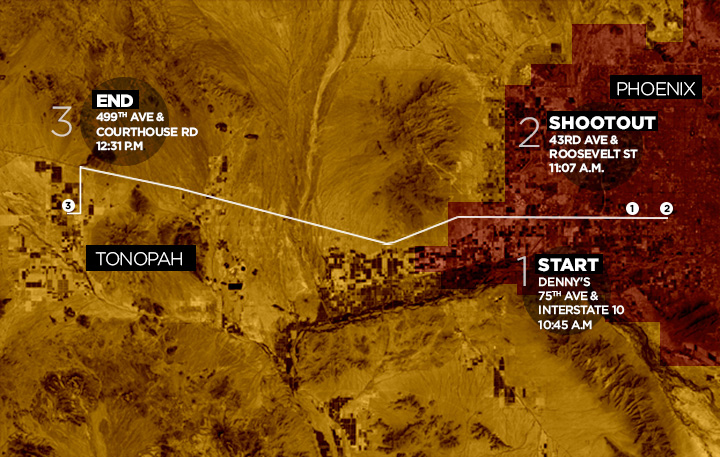

Denny's, 75th Avenue and Interstate 10, Phoenix, about 10:45 a.m.

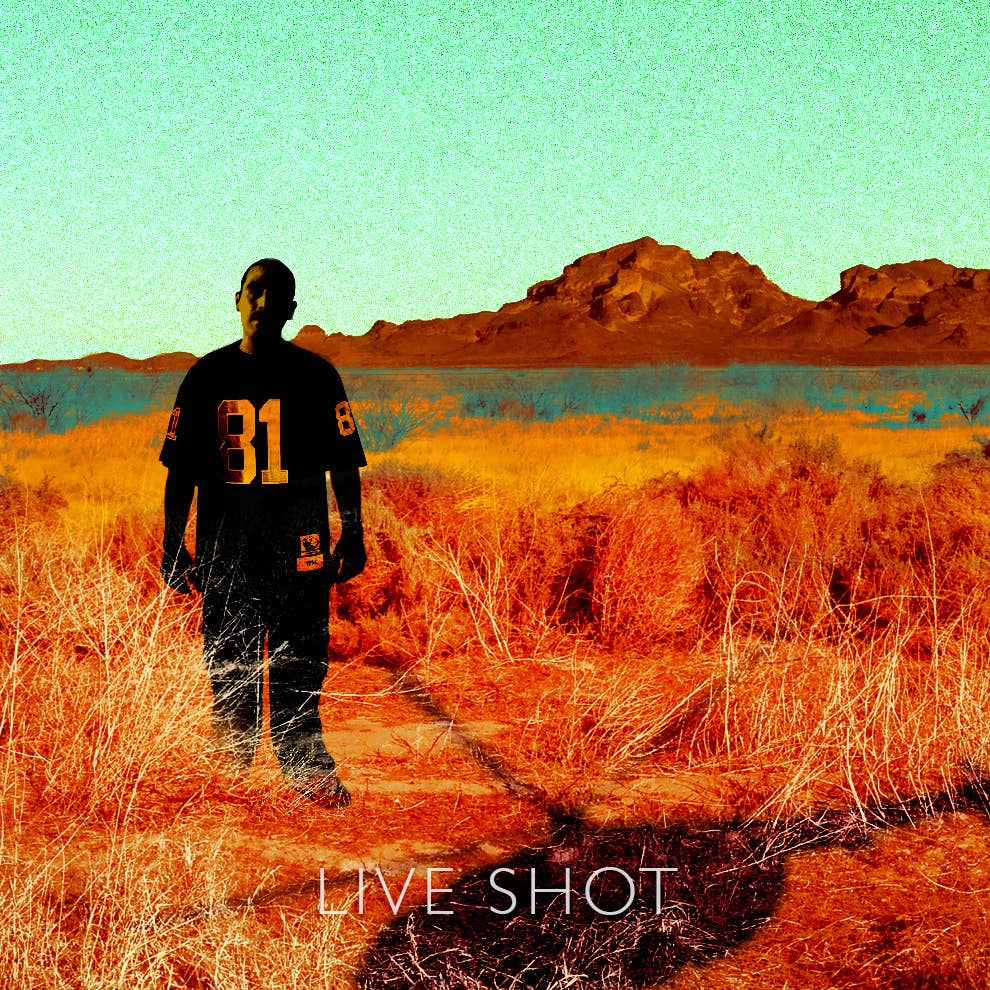

No one knows for sure how long Jodon Romero had been pacing outside that Phoenix Denny's. He doesn't attract much attention — this 5-foot-6, 33-year-old man in a black Raiders jersey. But then again, his .45-caliber Glock is hidden away in his waistband.

It's an unremarkable Friday, hot and swollen with the last gulps of summer. This appears to be Romero's second carjacking attempt of the day — his first try, at an apartment complex three blocks away, ended with the driver speeding off, the back of his car dented from Romero flinging a still-unidentified object at it.

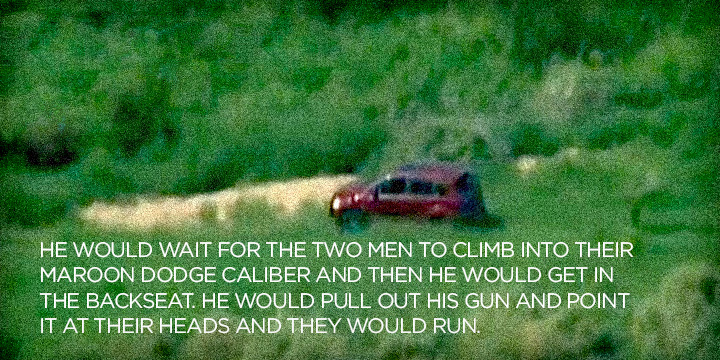

This time will be different. Romero will pick two younger men to follow. He'll wait for them to climb into their maroon Dodge Caliber and then he'll get in the backseat with them. He'll pull out his gun and point it at their heads and they will run.

By the time he'd stepped off the sidewalk, Romero may well have known how this story would end. But he couldn't have known there would be hundreds of thousands of people watching it.

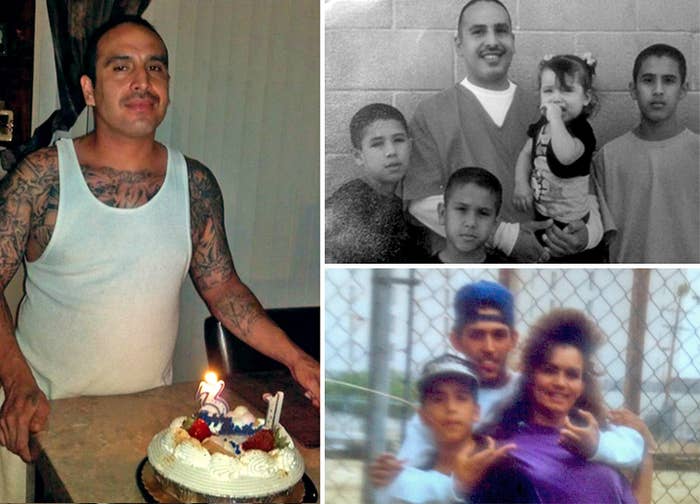

When Jodon Romero was 16, he watched his older brother die. It was 1:30 a.m. on Oct. 1, 1995. A few dozen people were hanging out in the parking lot of a Chevron Station on Tucson's South Side. Romero was there with his 21-year-old brother, Jason. A fight broke out, and Jason pushed his girlfriend out of the way. She ran toward his car while shots fired behind her. She later said Jason caught the bullet for Jodon.

Four others were hurt that night — three who survived gunshot wounds and one who was severely beaten. The Pima County Attorney's Office offered $2,500 for any information on those responsible, but the only lead came from a witness who saw a gray Cadillac with California plates leaving the scene after the shooting. Jason's killer was never identified.

"He blamed himself," says Nature Romero, Jodon's younger sister. She was 12 when Jason died. "My mom used to tell me Jodon's like a big marshmallow. He's tough on the outside, but really soft. He was more gentle than me. He took things so much to heart."

One year after his brother's death, Romero's father died of prostate cancer. Three years after that, when Romero was 20, his mother and her boyfriend were murdered in a home invasion in Phoenix — another unsolved crime.

Between his parents' deaths, Romero was caught with weed. He was charged with one count of possessing marijuana and one count of possessing drug paraphernalia, both felonies in Arizona. The first charge was dropped when he pled guilty to the second. His sentence was two years of probation.

Romero's record stayed relatively clean for the next decade. He started having kids — three sons — with one longtime girlfriend. He worked at an auto body shop and cooked big family dinners, traditional Valley Mexican plates.

"He cooked better than his girlfriends," Nature says. "And he used to love to always be with the kids. Playing basketball, doing barbecues. Oh my god, the barbecues. Randomly he would call me and say, 'Hey, mija, do you wanna grill? We'll throw some hamburgers and hot dogs on?' And we would laugh, like, 'Again?'"

Romero racked up two more marijuana violations — one in 2008 and one in 2010 — landing him, again, with probation. But in late 2009, he was caught owning a gun. As a felon, he was prohibited from carrying deadly weapons. This time, he was going to jail.

Denny's, 10:54 a.m.

Misael Avalos Hernandez turns around to look at the sweaty, nervous-looking man in the backseat. His friend is already outside the car, yelling at Hernandez to come on.

"Leave the keys," Romero says, pointing his gun at Hernandez's head. The 21-year-old slides out and runs back toward the restaurant. Inside, he asks the hostess to call 911.

Romero climbs into the driver's seat but hesitates before starting the car. Maybe he can't, or maybe he decides that he won't, or maybe he deliberately doesn't, holding off until he knows the 911 call has been made. It isn't until Hernandez comes back outside that Romero finally drives away.

A police officer arrives to take Hernandez's story. While he's running the boys' IDs, a call comes over the radio. The Caliber has been spotted about a mile away.

Nature Romero is sitting on her couch, facing me, her daughter fussing in her lap. It's March 2013. Keeping Up With The Kardashians is muted on her TV. The furniture is cozy and clean, various shades of wholesale brown. Family photos are everywhere: lining the walls, upright on end tables, pinned down with magnets on the refrigerator. The 6-year-old girl tunes out, fiddling with her mother's hands, while we talk about murder and barbecues.

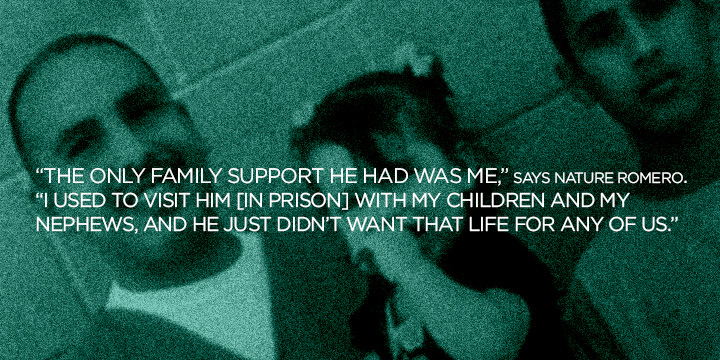

After Nature's parents died, it was just her and Jodon — no more siblings, no extended family. They were the survivors.

Romero's two-year, six-month prison sentence began at the Arizona State Prison Complex in Tucson on April 23, 2010. He was 30.

"I was the only one who went to see him," Nature says. "He told me, 'I don't know how people do it.' He said, 'I can't do it.' He wasn't made for that. Some people adapt to it. He never did. He could never get past that."

Nature plays me a video that Jodon recorded for his kids while he was in prison. He's sitting in a trailer, wearing his orange jumpsuit, reading Dr. Seuss.

Oh, the places you'll go! There is fun to be done!

There are points to be scored, there are games to be won.

And the magical things you can do with that ball

Will make you the winning-est winner of all.

Fame! You'll be famous as famous can be,

With the whole wide world watching you win on TV.

He reads slowly, bobbing his head along with the rhyme, barely looking up. But when he does, his eyes are soft.

I'm afraid that some times you'll play lonely games too.

Games you can't win 'cause you'll play against you.

All Alone! Whether you like it or not,

Alone will be something you'll be quite a lot.

"I love you kids. Just a little somethin', you know. Your dad was a little nervous. I don't like being in front of cameras. But ayyyyy," — a shy smile turns into a sloppy one — "love you guys. Sleep good. If you guys get lonely, put this on. Think I'll be comin' home real soon."

In prison, Romero worked as a kitchen helper, janitor, and groundskeeper. He had about a dozen disciplinary infractions, mostly minor disorderly conduct violations (horseplay, generally), though he was reprimanded once for drugs and once for tattooing. He was released on supervised parole on June 7, 2012, four months before his sentence ended. He was determined not to go back.

"We didn't have no family. The only family support he had was me," says Nature, staring past me at the empty air in her living room. "I used to visit him with my children and my nephews, and he just didn't want that life for any of us."

43rd Avenue and Roosevelt Street, Phoenix, 11:07 a.m.

A small army of undercover and patrol vehicles forms behind Romero. He drives east for five miles, ignoring their sirens, eventually turning onto a two-way street parallel to the freeway. He twists through a complex of commercial warehouses and truck depots. There's a stoplight ahead.

Emeterio Medina, a 32-year-old Phoenix Police Reserve officer, is lingering behind Romero in his marked Impala, staying a half-mile back in case Romero decides to ditch the Caliber and run on foot. Medina stops for a moment behind another officer's Chevy Tahoe. The officer is pulling out his stop sticks, but Medina waves to him that spikes aren't authorized yet. On the radio, they hear that Romero has made a U-turn. He's heading back toward them.

Medina stays in his seat. The other officer takes cover behind his SUV. Romero swerves toward them, and Medina draws his gun, keeping it low and out of sight. Romero passes by slowly, hunching over with his window down. As soon as the officers are behind him, Romero sticks his gun out the window and fires. The bullet hits the driver's door of Medina's car.

Medina doesn't have a clear shot to fire back. Two minutes later, Romero is surging down the freeway, heading west.

The first time Romero met with a parole officer, he was told he wouldn't "last out here," Nature recalls. Statistically, the officer had a point. In a 2011 U.S. Department of Justice study, 32% of 532,500 parolees were reincarcerated within a year of being released.

"That killed his self-confidence," Nature says. Romero tried to go back to his life before prison — back to basketball and barbecues — but the late summer brought trouble. He was seeing a woman, the mother of his fourth child (who would soon become pregnant with his fifth).

"The two of them had a volatile relationship," Nature says. "He loved her. They couldn't really make it work, but for the sake of his little girls, he wanted to make it work."

They got into a fight one Thursday night at her mother's house, and the cops showed up — Romero was reportedly intoxicated and disorderly. An Arizona Department of Corrections parole manager instructed police to either arrest him or transport him to an ADC facility, "neither of which occurred," an ADC spokesman later said. Instead, Nature says, the officers told Romero to report to his parole office first thing Friday for an appointment he already had scheduled.

Romero brought Nature with him the next morning. He met with a supervising officer and admitted to fighting with his girlfriend. "He was ready," Nature says. "We hugged, we said bye. He was ready to go back to prison that day. His mind-set was there." The officer gave Romero some policies to comply with — go to counseling, do a urine test, avoid contact with the woman — but otherwise, he could go home.

"I was like, 'See? You were worried over nothing!'" Nature says.

They were back at Nature's house, getting ready to eat lunch, when she got a call from the supervising officer. There was a miscommunication between the officer — who apparently didn't know about Romero's police contact the night before — and the parole manager. Now they both wanted Romero back in the office.

"That's where everything went downhill. When I took him that morning, he was ready to go. But it's because they let him go. They told him everything was fine, they thought he was OK..." Nature trails off. "Of course his mind-set changed. He was relieved he wasn't going, and then they threw it on him."

He told his parole officer he'd come back by the end of the week, but he kept putting it off. On July 20, a warrant for Romero's arrest was issued. Six weeks later, on Labor Day weekend, Romero was pulled over, Nature says. He fled and escaped — an offense that would add years to his already guaranteed prison time. Within a few weeks, the U.S. Marshals showed up at Nature's door, looking for her brother.

Salome Road, Tonopah, 12:24 p.m.

Romero holds steady on the 10 for about an hour. The city becomes the suburbs and then the desert, speckled with rest stops and gas stations. He drives and drives, zigzagging past other cars at 90 mph toward the California border, and soon it seems like he's going to drive until he runs out of gas — the way a lot of car chases end.

But then he exits in Tonopah — not even a small town but a "census-designated place," home to 60 people, a few farms, and the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station. Off the interstate, he barrels down roads that alternate between pavement and gravel without much warning, before finally turning onto a dirt path in a patchy field.

He rolls forward for 40 yards, then stumbles out of the car. Above him are two helicopters: one belonging to KSAZ, Phoenix's Fox affiliate, and one operated by the Phoenix Police Air Support Unit. From above, Officer Jeffrey Hughes records every move Romero makes.

"As he exited, he looked around, carrying something in his hand. He then leaned back into the vehicle manipulating something in his hand."

The driver's door is still open when Romero begins sprinting — arms flapping, pants drooping.

"He then ran a short distance before falling down in the dirt. [He] got up and walked southeast toward some tall bushes."

He pushes through the brush, finally stopping in a small patch of dirt. He shuffles from side to side.

"He then positioned himself in the direction of the officers that were approaching from the north."

He spreads his legs slightly, knees locking, as he fumbles with something in his hands. The white of his jersey is beaming, the sun beating down on his back.

Television stations didn't start routinely covering car chases from the sky until the 1970s, about a decade after the first news helicopter took flight. But the first major live police chase didn't air until 1992, when Los Angeles's KCOP famously broke in during a rerun of Matlock. A 22-year-old man suspected of murdering a hitchhiker was leading police on a 300-mile chase, and viewers were transfixed. When KCOP cut back to Matlock before the chase ended, station officials reportedly received hundreds of calls demanding they bring the chase coverage back. (They did.)

The man eventually ran out of gas and was shot during a standoff with police, right on TV. The Los Angeles Times called the footage a "marriage of technology and tragedy."

By the end of the 1990s, news choppers were ubiquitous — and the source of deep competition between networks, especially in Los Angeles, the car chase capital of the country. There are close to 1,000 pursuits in L.A. each year, roughly 250 of which require air support.

Robert Tur, the helicopter reporter who provided KCOP's aerial footage during that historic '92 chase, estimates that "7 or 8%" of the 230 car chases he's covered in L.A. have ended in death.

"Almost because of your bird's-eye view, you can tell the future. You can see the traffic. There have been numerous incidents where I've seen an accident about to happen," says Tur, who retired in 2000 after 10,000 hours of flight. "It's despair. I hate seeing it. It's a terrible feeling to see what's coming."

Tur calls himself the father of modern news helicopters, and for good reason. In 1992, he captured footage of Reginald Denny being brutally beaten during the L.A. riots. In 1994, he offered the first live shot of O.J. Simpson fleeing police in his white Bronco, perhaps the most famous car chase of all time. Both segments were hugely popular among viewers, and newsrooms allocated their resources accordingly.

"What the news helicopter did was give us real insight into what was really going on," Tur says. "People got to see things that they never saw before." But more live chopper coverage also meant more opportunity to inadvertently broadcast graphic images.

In 1998, 40-year-old Daniel Jones parked his truck on a Los Angeles freeway, fired several gunshots into the air, and unfurled a banner that read "HMOs are in it for the money!! Live free, love safe or die." He ignited a Molotov cocktail, setting his truck and himself and his dog on fire, and eventually put a gun underneath his chin. Cameras rolled throughout the entire bizarre episode. This time, the Times called it a "quintessentially Los Angeles story," complete with "guns, traffic jams, cellular phones, swarms of news helicopters, desperate self-promotion — and a sudden, tragic, cinematic conclusion."

If L.A. is an incubator for dramatic car chases, Phoenix is more of a swarming petri dish. The two cities have similar highway systems and commuter cultures, and Phoenix once had more motor vehicle thefts than any other city in the country — though police have seen a decline over the last few years.

On the first day I was supposed to meet Nature in Phoenix, I got stuck on the freeway, traffic barely moving for nearly an hour. A few miles away, two men and a teenage girl were fleeing police in a stolen yellow Honda Civic Coupe. They would lead authorities on a 20-mile chase before eventually rolling off the road into a desert embankment. They walked away in handcuffs.

Friday, Sept. 28

Fox News Headquarters, New York, 12:26 p.m. (3:26 ET)

Megyn Kelly's America Live had been the first national program to broadcast Romero's chase, just before 3 p.m. ET. Trace Gallagher narrated as Kelly chirped in with her daytime-news deadpan: "Somebody carjacked a Dodge Caliber?" Minutes later, Live transitioned to Studio B. "Shepard's up next," Kelly said. "Shepard. Car chase. You know you should stay tuned."

Over the next 30 minutes, the signal goes in and out, snapping viewers between a black screen, footage from minutes ago, and live pictures of the Caliber darting through farmland. The local Fox affiliate ends its coverage with its noon show. The national Fox News broadcast goes on.

"Look at this," Shepard Smith says. "Dingbat here has gotten off the freeway... This guy is right smack-dab in the middle of nothingness… Maybe he's a farmer in his day job. Maybe he's just a part-time shoot-at-cops suspect…"

The signal continues to falter, though it's steady by the time Romero turns onto that last dirt road.

"Maybe this is home," Smith says. "You never know. Maybe he's taking the carjacked victim to the victim's house."

There is no victim, and there are no houses even remotely within sight. But narrating car chases is Smith's specialty. He knows the vocabulary. He knows how to improvise. He knows when to make it light and fun, and when to make it intense and frightening.

"Now this scares me. What are you doing out in the middle of nowhere, getting out of the car? Uh. I'm just not sure about this. He's getting things out of the vehicle, clearly. It doesn't appear that there's anyone else with him. Well, you know, you wait for the end of these things and then you worry about how they may end. There's nobody else around him. Um, this makes me a little nervous, I gotta tell ya. A little nervous, I gotta tell ya."

"I'm just not really sure," Smith continues, "but he is looking kind of erratic, isn't he? Um. I don't know. No. And. Look at this. He's just running. Oh my. Well, it looks like he's a little disoriented or something. It's always possible guy could be on something. Um."

There's a sudden deep gasp — loud enough to be picked up by Smith's mic, but muffled, as if whoever made the noise tried to contain it with his hands.

"Oh — get off, get off, get off, get off, get off, get off, get off, get off, get off it. Get off it! Get off it! Get off it!"

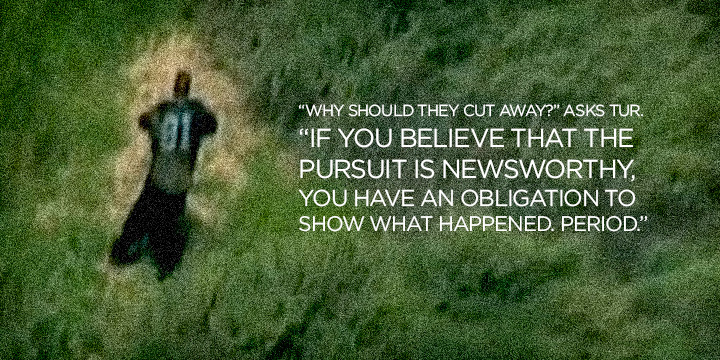

When I tell Robert Tur about Romero's live TV suicide — about Fox's failure to use its five-second delay, or even "go wide" with the chopper camera, effectively blurring out the grisly moment — I have to hold the phone back from my ear.

"Why should they cut away? I'm in the news business! We produce news stories, and this belief that the news media is there to censor is ridiculous," says Tur, who also hosted a MSNBC show called Why They Run in 2007. "If you believe that the pursuit is newsworthy, you have an obligation to show what happened. Period."

It's a controversial opinion — one that Tur may have had more support for 10 or 20 years ago, when live footage was truly live. But now there's YouTube and technology that allows you to quickly rip footage off your television and put it onto YouTube. "Live" can live forever online, and that makes the ethics of covering car chases a lot more confusing.

Around 2002, Al Tompkins of the Poynter Institute coauthored guidelines for broadcast journalists to consider before airing live car chases. They're meant to ensure that TV stations show police pursuits for their news value — not for their entertainment value. They include questions like, "Beyond competitive factors, what are your motivations for going live?" and "Are you prepared to air the worst possible outcome that could result from this unfolding story (such as, a person killing himself or someone during live coverage)? What outcomes are you not willing to air?"

Ten years later, Tompkins stands by his guidelines, particularly in light of technological developments like YouTube. "Imagine for a minute that that's your loved one or someone that you care about [being chased]," he says. "It seems doubly damaging that it could be preserved for someone else's leisure viewing."

Tompkins says he isn't opposed to all media coverage of car chases, but he thinks there's little defense for airing them live on national broadcasts. "Reasons for showing it locally are very different than reasons for showing it nationally," he says. "In a rural area, a chase can have real newsworthiness. It's a story of significant local relevance."

After a commercial break, Shepard Smith returned that Friday afternoon with a somber apology: "Well, some 'splainin to do ... We really messed up. We're all very sorry. That didn't belong on TV. We took every precaution we knew how to take to keep that from being on TV. And I personally apologize to you that that happened."

Later that day, Michael Clemente, executive vice president of news editorial at Fox, issued a statement as well. "We took every precaution to avoid any such incident by putting the helicopter pictures on a five-second delay," he said. "Unfortunately, this mistake was the result of a severe human error, and we apologize for what the viewers ultimately saw on the screen."

499th Avenue and Courthouse Road, Tonopah, Arizona, 12:31 p.m.

It's over in three seconds. When the police arrive, Romero is facedown in a pool of blood, hands tucked under his body near his waist, along with his gun. Three officers stand by guardedly, trying to determine if he's still alive.

A fourth officer arrives and rolls Romero over. A faint heartbeat is detected, so the officer begins chest compressions. Two others relieve him, continuing CPR and strapping an oxygen mask to his face. When the Harquahala Valley Fire Department arrives, Romero still isn't responding. Soon he has no pulse at all.

There aren't any hospitals for miles, so a doctor determines time of death over the phone: 1:14 p.m.

Testimonies are recorded, briefings are given, inventory is taken. The first responders had cut through Romero's clothes — through his Tim Brown jersey and his black Dickies with the white bandanna tied through the belt loop. In his right pocket, an officer finds a plastic bag of marijuana — about four grams — and a disposable lighter. In the other, a gram of crack cocaine and a live round of ammo.

Five hours later, as the sun sets, a medical examiner removes the body.

The story could have ended there. And maybe, if it had happened during Tur's tenure in the '90s, it would have. But Studio B's viewers weren't the only people following the chase. Dozens on Twitter — reporters, editors, a community of national news breakers and consumers — were broadcasting it too. It was a slow news day.

There had already been another car chase that morning. A pursuit developed in Los Angeles around 8:30 a.m. local time — 11:30 a.m. on the East Coast — and ended half an hour later with the peaceful arrest of two carjacking suspects. BuzzFeed's Mike Hayes was among the first to tweet a link to the chase's live feed. Twenty minutes later, a Bloomberg editor tweeted, "The feeling you get when you come back to your desk with lunch and a car chase is on must be what it feels like to win the lottery." Five retweets. This is Twitter on a late summer Friday.

Fox News Channel ignored repeated requests to participate in this story. But if you want to know the company's philosophy on police pursuits, just ask its anchors.

"Car chases are like potato chips," Red Eye host Greg Gutfeld said in 2011. "They're loud and crunchy, and once you start, you can't get enough."

car chase!!!!!!!

When the gunshot fired and Romero fell to the ground, there was a half-second of silence. Then, an eruption.

Holy crap. The suspect just killed himself on live TV.

OH MY GOD I JUST SAW THAT CAR CHASE GUY SHOOT HIMSELF IN THE HEAD ON FOX NEWS. shepard smith is PISSED. omg. omg.

Holy shit, Fox News. Try to cut before the guy shoots himself in the head next time.

At that same moment, in a suburb 2,500 miles away from Studio B, the sister of "THAT CAR CHASE GUY" was watching too.

Friday, Sept. 28.

A cul-de-sac in west Phoenix, Arizona, 10:30 a.m.

Nature's phone glows with a text from Jodon: "Thanks for everything."

Earlier that morning, she was getting her kids ready for school when the mother of Jodon's children called, saying she couldn't get a hold of him. Neither, it turned out, could Nature.

She was concerned; Jodon seemed unhappy lately, running and hiding from an arrest that seemed inevitable. Finally, he called her back. They spoke for a few minutes, but Nature still felt uneasy. She had woken at two that morning with an eerie, queasy feeling, and it hadn't left her yet.

About an hour later, she turns on the TV, flipping through channels before landing on Fox. A man is fleeing police after stealing a car from a Denny's. It happened less than a mile from Jodon's house.

She waits a few minutes, then dials the non-emergency police line: "I have reason to believe that's my brother."

It's agony. She feels gutted, hope drained, as she waits for a detective to call her back. Miles away, Jodon zooms past cars and weaves through lanes — but Nature doesn't see a car chase. She sees a man — her brother — deliberately orchestrating something. Stealing some kid's car, even though he had a nicer, faster truck at home; shooting at the door of a police car, even though officers are clearly within his aim. She sees a man purposefully backing himself so far into a corner that it seems like he has no other option.

Nature looks at the last text from Jodon. He was thanking her, again, and telling her that no one else ever loved him like she did.

There are dozens of reasons Nature feels sad and angry and confused about her brother's death, but one trumps the rest: "On the news, they publicized that he was a violent offender and he went to jail for violent crimes, and it was never nothing like that," she says. "He wasn't a violent person at all. He was just like a genuinely good person."

"It's one thing to lose somebody under those circumstances," she continues. "But then when you're grieving and going through that, to have to see it all over the internet, it's unspeakable."

Over the last 18 years, Nature's family has shrunk from five to one. Now she's approaching 30, with two children and a solid job as a nursing assistant, but her home is full of urns. She shows me Jodon's, on a shelf in her dining room, next to a photo of him and a small pile of Jolly Ranchers — his favorite. She answers all of my questions openly, often through tears. But when she asks me a question — "Did you watch the chase?" — I stumble.

I was born and raised in Phoenix, but I was sitting at my desk in New York when I saw the first tweets about a car chase in Arizona. I began tuning in while Romero was still on the westbound I-10 — a stretch of highway I've spent an ungainly amount of my life driving. I watched him swiftly switch lanes and narrowly pass semi-trucks on the shoulder, and I thought of every time I'd seen a frustrated driver pull the same hasty moves on that long, dull desert road (albeit without a dozen patrol cars following them). Yes, I watched the chase. Yes, I saw its awful conclusion.

But I also reported on it. I wrote about Fox's mistake, and uploaded a video of Fox's mistake, and helped make Fox's mistake go viral. How do you tell a grieving sister that? Because of a "severe human error," thousands watched her brother die in real time, but because of you, hundreds of thousands watched it later?

You tell her the truth. And then you listen as she tells you about her brother — about all the details that weren't on the news that day. About his personality (always laughing), his hobbies (remodeling his house), his five children (the oldest is 15, the youngest was born in March), and his funeral. (A formal church ceremony, then a more casual memorial. They played Tupac.)

Car chases can be thrilling to follow, but they're often consumed with little context. When we watch a chase, we never really know the full details of how or why it began. Shepard Smith didn't know the man he called a "dingbat" had no history of violent crimes. The scores of people watching the chase didn't know Romero was a father of four with a baby on the way. I didn't know Romero had lost all but one of his relatives by the time he was 21.

Before I leave her house, I ask Nature what she would say to the people responsible for airing — and sharing — her brother's death, if they were, say, sitting cross-legged on her couch right now.

"They can never know the kind of impact that leaves, the lasting impression on us."

Her voice is charged, but her expression is exhausted.

"To see my brother shoot himself and to see him fall down — that's embedded in my head forever."