Not many people know I'm a survivor, because it's been less than a year since my assault. After it happened, I opened up to a close friend, and his response was, "I guess I just never expected it to happen to you, because you're so smart and so strong." Many people I've told have echoed that sentiment. For a 19-year-old, I've done a lot of media training; I'm very involved in women's rights, I work with the International Youth Council, and I've done a number of internships in D.C. I feel it's important to point this out because shortly after my assault, I was contacted by someone making a documentary on survivors through my work with the Feminist Majority Foundation. I agreed to participate, because I felt I was expected to speak out. To be strong. To be a voice for the voiceless.

A few weeks later, I was on camera as she asked me questions about my assault. When did it happen? Was it someone I knew? Did I have any support afterwards? I can speak in front of a crowd of about 100 people and be relatively calm, but I trembled as I struggled to pull words into coherent sentences, to sound like I knew what I was talking about.

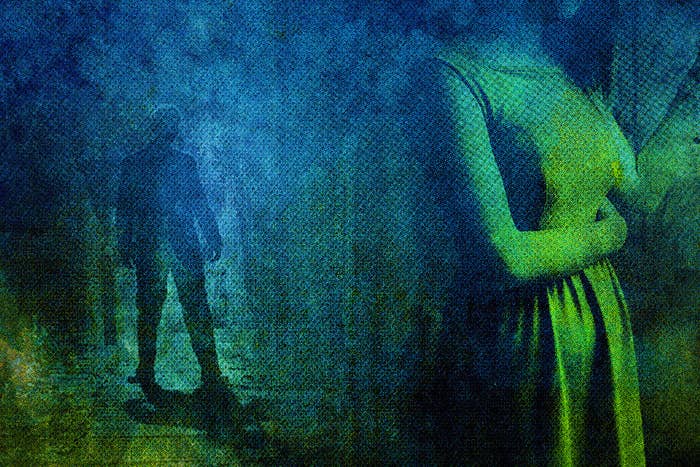

I remember my rape. I remember waking up in pain. I remember fear. I remember the morning after, commuting to work in a stunned silence. It felt like I was in a timeless void, and the world around me just kept turning. I remember my fellow interns asking me what was wrong, my normally expressive voice stuck in an emotionless monotone. I remember deciding to speak to both my internship supervisors about it, deciding to speak to women I had known for only a few weeks because I had recently moved and had nobody else. I remember monotone, I remember silence; I remember disbelief.

Now, I was incredibly lucky to be in a situation where I was surrounded by strong and supportive women. Women with the understanding, knowledge, and resources to aid me by removing me from a toxic environment and providing me with medical support, although they had known me but a few weeks. Women who helped me feel valid in my pain and fear. I am also lucky in that I was not assaulted at college, and that by taking action my educational future was not put into jeopardy. So many victims are not allowed any of these things.

But when it came to talking to someone I barely knew so matter-of-factly, taking this story I had little time to cope with and wrapping it up into a neat little package, I felt I was failing.

I was failing simply because I felt something many survivors do on a daily basis: Blame. Guilt. Doubt. What if I hadn't said "no, thank you" loud enough? What if I had been less polite? What if I had been more aggressive? What if, for once in my life, I wasn't afraid of offending someone and actually stood up for myself? What if I had run screaming out into the snow and spent the night freezing in the street? Would that have been better — would I still have been raped then?

I felt this unbearable pressure that if I didn't present my story correctly, the audience would feel the same doubt I did. They would look at me like my peers did; they'd say, "She's so smart and so strong, she works in women's rights and is familiar with this issue; surely she can't be a rape victim."

There's so much pressure put onto victims to present our story in the "correct" way. Your account shouldn't make someone feel uncomfortable. It shouldn't alienate them. What if someone were to feel, I don't know, guilt after hearing it? What if they realized they were an active participant in rape culture themselves? The activist in me wanted people to understand the pain and confusion, the stigma and fear associated with being a survivor. I felt like I was speaking on behalf of all the survivors I'd met, and perhaps even the survivors I hadn't. But the young lady in me felt this pressure not to ruffle any feathers. Not to risk losing something else. Even now, writing this article, I am terrified and on edge, because charges were never brought against my rapist.

Still, trembling and on the verge of tears, I sat through the entirety of the videotaped interview. After a sleepless night full of all these doubts, I sent an email to my interviewer. I asked politely if my interview could be removed from her queue for editing, as I no longer wanted to participate. And she said yes.

Here's the thing about rape that most people seem to get: it's violating. It requires a lack of consent. It's an event full of pain and regret.

Here's the thing about sharing a rape victim's story without their permission that most people don't seem to get: It's violating. It requires a lack of consent. It's an event full of pain and regret.

If someone agreed to have sex with you earlier in the day, but when it came time to actually do it they no longer consented, and you had sex with them anyway, was it rape? When you share the story of a rape victim without her consent, even if she formerly consented, it is a complete re-violation of her personal space and narrative. It doesn't matter why Jackie, the subject of Rolling Stone's article about UVA and sexual assault, later retracted her statements. And the aim of this article is not to justify or analyze her hesitation. What I'm saying is this: By publishing an article that the victim retracted her support of, Rolling Stone essentially violated Jackie, and every other survivor, all over again.