The Royal Bank of Scotland killed or crippled thousands of businesses during the recession as a result of a deliberate plan to add billions of pounds to its balance sheet, according to a leaked cache of thousands of secret documents.

The RBS Files – revealed today by BuzzFeed News and BBC Newsnight – lay bare the secret policies under which firms were pushed into the bank’s feared troubled-business unit, Global Restructuring Group (GRG), which chased profits by hitting them with massive fees and fines and by snapping up their assets at rock-bottom prices.

The internal documents starkly contradict the bank’s public insistence that GRG acted as an “intensive care unit” for ailing firms, tasked with restructuring their loan agreements to “help them back to health”.

RBS has repeatedly denied allegations that it destroyed healthy businesses for profit – first raised in a damning report on its treatment of small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by the government adviser Lawrence Tomlinson three years ago. The bank paid the magic circle law firm Clifford Chance to conduct an “independent investigation” that found “no evidence” of the claims, and an official inquiry by the banking regulator has been long delayed.

The RBS Files now reveal for the first time that, under pressure from the government, the taxpayer-owned bank ran down businesses in its restructuring unit as part of a deliberate, premeditated strategy to cut lending and bolster profits. And they show that GRG, ignoring repeated warnings about conflict of interest, collaborated closely with the bank’s own property division, West Register, to buy up heavily discounted assets it had forced its customers to sell.

When confronted with the leaked evidence last week, the bank made its first major admission: “In the aftermath of the financial crisis we did not always meet our own high standards and let some of our SME customers down." But it continued to deny that it had “targeted businesses to transfer them to GRG or drove them to insolvency”.

The files reveal that 16,000 firms were sucked into the restructuring unit after the financial crash – including care homes, hotels, farms, and children’s centres. BuzzFeed News has spoken to 15 small-business owners who say their healthy firms were ruined after they were put into GRG. Some have lost their homes, marriages, and health as well as the companies they built from scratch and all their assets.

The documents – comprising internal emails, confidential memos, secret policy documents, minutes, and financial records leaked from inside the bank by an anonymous whistleblower – today show:

RBS managers encouraged employees to hunt for ways to boost their bonuses by forcing customers into loan restructuring in order to extract heavy fees as part of a profit drive nicknamed “Project Dash for Cash”.

Firms that had never missed a loan payment were pushed into GRG under the bank’s secret policies for reasons that had nothing to do with financial distress, including for telling RBS they wanted to leave the bank, falling out with managers, or threatening to sue over mistreatment.

Once in GRG, firms were hit with crippling fees, fines, and interest rate hikes that could run into seven figures, helping to net the restructuring unit a profit of more than a billion pounds in a single year.

Contrary to claims by the bank, there were no Chinese walls between GRG and West Register bosses, who sat together on both the controlling committee that held sway over which businesses were transferred into the restructuring unit and the property acquisition committee that signed off the bank’s bids for their distressed assets. Auditors repeatedly warned about perceived conflicts of interest in GRG.

The property division, which amassed assets worth £3.3 billion during the crisis, was passed information that was not available to other bidders when it wanted to acquire properties from businesses in GRG. In contrast to what RBS executives told parliament, properties could be sold to West Register without being advertised on the open market.

Staff were told to conceal conflicts of interest from customers when demanding cheap shares in their businesses or stakes in their properties.

The revelations will pile pressure on the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) to conclude its long-delayed inquiry into RBS’s treatment of its small-business customers. Tomlinson, whose report triggered the FCA probe, said the documents obtained by BuzzFeed News “seem to prove that there was a policy within RBS to destroy businesses, to add value to their balance sheet through GRG”. He urged the regulator to act decisively: “Those people should now be brought to book.”

Alison Loveday, who says her law firm Berg has dealt with “hundreds of cases” in which healthy firms were “devastated by GRG’s activities”, called on the FCA to take urgent action to ensure business owners are “properly compensated for the loss and damage they have suffered”. She blamed GRG’s heavy-handed tactics for causing “heart attacks, family breakdown, and even suicides”.

The RBS Files raise serious questions about the basis on which Clifford Chance exonerated the bank in its 2014 report, which was welcomed by RBS chief executive Ross McEwan at the time as evidence that GRG was “a pretty good unit”. The documents also expose the hollowness of the evidence given to the Commons Treasury select committee by RBS executives, who told MPs the restructuring division’s “main objective is to restore the customers’ health and strength” and denied 27 times that it sought profit.

Derek Sach, who headed GRG, and Chris Sullivan, the bank’s then deputy chief executive, testified that staff were not put under pressure to increase customers’ fees and that properties acquired by West Register were “always marketed on the open market” – claims the internal documents contradict.

The bank’s chairman, Sir Philip Hampton, later had to write to the committee to withdraw the executives’ repeated assertion that GRG was “absolutely not a profit centre”, claiming they had made “an honest mistake”. The RBS Files reveal that both Sach and Sullivan were sent regular updates on GRG’s “profit and loss” performance, which itemised revenues from fees, interest rate hikes, and asset acquisitions that far exceeded its costs. Sach, who told MPs that GRG “does not contribute to the bank’s profits at all”, was responsible for signing off internal documents that described the unit as “a major contributor to the Group’s bottom line”.

The white-haired restructuring boss emerges from the documents as an all-powerful puppet master, simultaneously heading the management committee that held sway over which businesses were transferred into GRG, the West Register committees that decided which assets the property division should acquire, the asset purchase committees that signed off its major bids, and the risk and audit committee that scrutinised the restructuring division’s work. Repeated warnings from RBS’s external auditors about the “reputational risk” arising from this apparent conflict of interest were ignored. Sach declined to comment when contacted by BuzzFeed News.

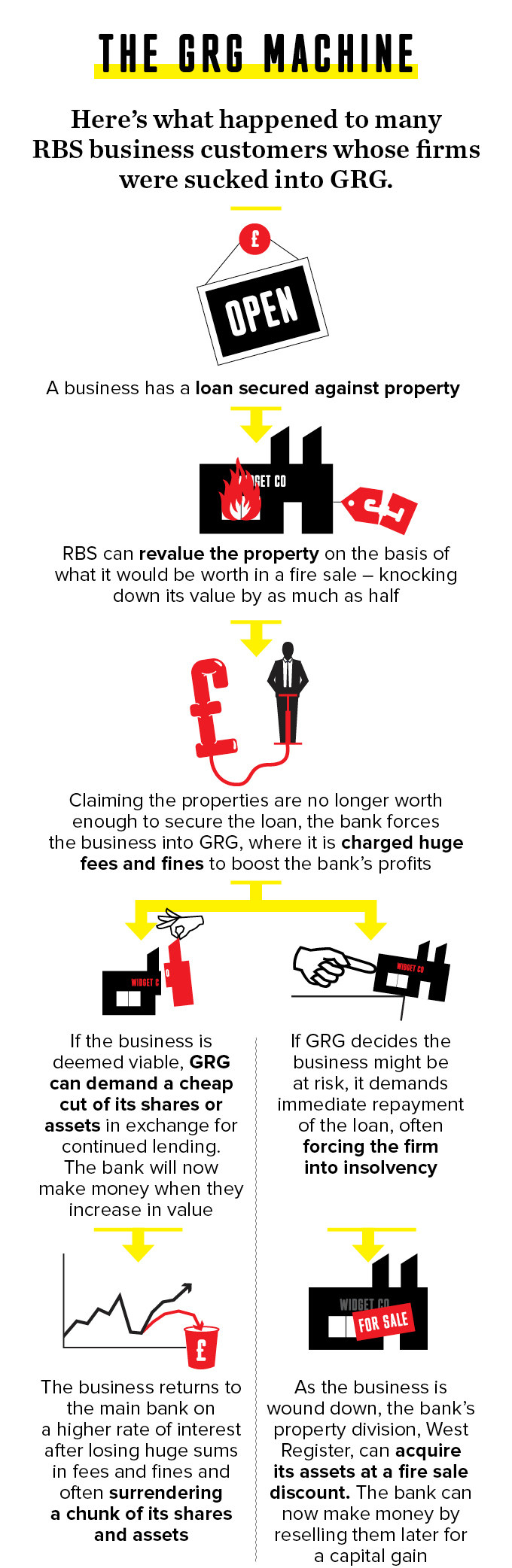

The documents show GRG staff were asked to split customers into two groups – those considered “viable” and those “the bank would like to exit”.

“Viable” firms would have their debts restructured to boost the bank’s revenues and often be forced to surrender cheap stakes in their assets or equity to GRG’s investment arm. But if firms were considered a potential risk, even if they were not insolvent, staff were instructed to “exit” by “placing pressure on the company to repay the debt as soon as possible through refinancing, realisation of assets, and possibly commencing insolvency proceedings”.

When assets were sold out of insolvency, often for dramatically discounted prices, West Register would be brought in to decide if it wanted to make a bid, with GRG managers privately guiding its staff on just on how much they would need to offer.

RBS has repeated its denial that the property division profited by buying assets cheap and selling them on for an inflated price. But confidential internal audit documents note that West Register is “used by GRG to acquire property assets from distressed situations” and “seeks to exit properties via a future commercial sale in order to extract maximum economic value” that “can often result in a capital gain in relation to the original property acquisition”.

In a statement, RBS said it had lost £2 billion on its loans to small and medium-sized businesses during the financial crisis. It said RBS did not make an overall profit from GRG’s activities – the restructuring unit’s revenues did not exceed the losses the entire bank suffered on business loans gone bad after the crash. But its statement acknowledged, for the first time, that “a number of our customers did not receive the level of service they should have done” in GRG.

“We could have managed the transition to GRG better and we could have better explained to customers any changes to the prices or fees we were charging,” its statement said. “We also did not always handle customer complaints well. As a result, a number of our customers did not receive the level of service they should have done or, importantly, that they would receive now.” The bank also said it would change its internal policies so that a customer litigating against the bank would no longer be among its restructuring “triggers”.

"West Register seeks to exit properties via a future commercial sale in order to extract maximum economic value when market conditions permit. This can often result in a capital gain in relation to the original property acquisition"

But RBS still insisted that “GRG’s role was to protect the bank’s position, where possible by working with distressed businesses to return them to financial health,” and said it had seen “nothing to support the allegations that the bank artificially distressed otherwise viable SME businesses or deliberately caused them to fail”.

A cornerstone of RBS’s denial that it systematically destroyed small businesses has been the insistence that it had no reason to push good customers into difficulty. But the files reveal how government pressure to reduce its loan exposures, coupled with the opportunity to raid the cash, equity, and assets of businesses going under, gave the bank a powerful incentive to pull the plug on thousands of its customers.

The government and regulators pushed RBS to achieve three main goals after the bailout. First, they pressed the bank to reduce its exposure to property loans, which were a main cause of the financial crisis. Then they required RBS to increase its capital reserves as a buffer against losses. Finally, they pushed for the bank to make more money overall, so that it could increase its lending to new businesses to aid the economic recovery, and so the government could sell its ownership stake at a profit. RBS devised a strategy to do just that.

The plan – which bosses told staff the government had “endorsed and agreed” – was to offload tens of billions of pounds’ worth of business loans that the bank had deemed “non-core”. It was widely hailed as an essential move to shore up the bank’s finances after the crash and protect the taxpayer's investment.

But the RBS Files now reveal GRG played a central role in the delivery of that plan, acting as a clearinghouse for many of those “non-core” businesses as the bank pushed them towards the exit door: generating bumper revenues by extracting massive fees and fines, clawing back loans secured against property, seizing chunks of their equity, and offloading their assets. Through West Register, the bank could acquire their prime properties at fire-sale prices, converting them from risky loan exposures into owned assets that the bank planned to sell off later for a capital gain. And, by quarantining the properties in a network of subsidiaries owned by West Register, the bank substantially reduced the amount of capital it had to freeze on its balance sheet as a regulatory buffer against potential losses, freeing up extra cash.

The inside story of how that plan was put together in the teeth of the financial hurricane – and went on to cause misery for business owners across the country – is revealed today for the first time.

As summer turned to autumn in 2008, panic was pulsing through Royal Bank of Scotland’s global headquarters in Edinburgh. The credit crunch had sunk its teeth deep into the bank’s balance sheet, and it was haemorrhaging money at a terrifying rate. The Scottish giant had swelled to become Britain’s biggest financial institution, amassing global assets worth £2.2 trillion in a period of frenzied acquisition during the boom years, but now it was perilously close to insolvency. Leaked emails reveal that, already, the British firms that banked with RBS were being made to feel the pain. Managers rushed to bleed business customers for extra fees and higher interest rates in a frantic drive to transfuse the bank with cash – and to bump up their own bonuses to boot.

“Project Dash for Cash: This will principally come in the form of Restructuring/Exit fees. I'd like you to think of all those customers where they have breached covenant or could breach covenant if revalued now”

Rhydian Davies, RBS’s gregarious head of property in the south region’s corporate banking division, called a meeting of his managers and told them he had come up with a plan to get them through the tough times that September. Davies had a boyish fondness for nicknaming his initiatives with a touch of derring-do, so he had called his proposal “Project Dash for Cash”. The region was falling way behind on its financial targets, and it needed to use some clever tricks to squeeze more money out of its customers. “The only significant impact that can be made will be in cash fees,” he reminded them in a follow-up email after the meeting. “These will principally come in the form of restructuring/exit fees.” Davies was effectively asking his staff to rip up customers’ original loan agreements and either charge them more to continue borrowing by “restructuring” the deal with higher interest rate and fees, or charge them exit fees if the loans were not renewed.

To do that, the bank had to demonstrate that customers had breached a “covenant” in their loan contracts. Internal guidance to managers explained that this would “enable the bank to break the ‘agreement’ with the customer” and “either call for repayment or renegotiate the terms” of the loan. Helpfully, tumbling property prices across the country offered a neat solution: A vast proportion of RBS’s business loans were secured against real estate, and most agreements contained a “loan-to-value” covenant stipulating that the customer’s borrowing must not exceed 70-80% of the value of their assets. The dire economic outlook made it easy to argue that a fall in the value of properties put customers in breach of their loan-to-value (LTV) covenants, and that meant the bank got to break the deal.

So, after the meeting, Davies forwarded managers a “target list” of loans secured against property assets and asked staff to scour it for businesses they could force into new, costlier contracts. “I’d like you to think of customers where; They have breached covenant [or] Could breach covenant (if revalued now),” he wrote, exhorting them think of “our bonuses” and “our pride in delivering” as they sought reasons to void their customers’ loans. Davies, who did not respond to a request for comment, asked staff to keep a log of their work in a spreadsheet he had waggishly titled the Blue Peter Cash Appeal, and signed the email “Rhyds”.

The problem for the bank’s customers was that property valuations are, as its executives later admitted in their evidence to parliament, “an art as well as a science”, and RBS often evaluated properties in a way that dispensed with any independent checks and balances.

In order to claim a business needed to have its loan “restructured”, RBS managers needed only perform an internal “desktop” valuation – effectively just estimating how much its properties might be worth. RBS’s auditors raised concerns that the “valuation of properties might be manipulated as valuation is performed internally”. What’s more, during the crisis, managers tended to assess the value of customers’ properties on the basis of how much they would fetch not in an ordinary sale but in a fire sale, with a short marketing window. That tactic alone could massively depress the estimated purchase price. Armed with these advantages, it was not difficult to find customers who “could breach covenant (if revalued now)”.

“There were a lot of conditions the bank would use to invoke failings or get a revaluation done,” one former RBS insider told BuzzFeed News and the BBC on condition of anonymity. “That’s what the bank invoked when it all went horribly wrong in 2008 to get everything restructured. You say it was £230,000 two years ago, it’s now £180,000, you’re under water now.” That, he said, was “where they hit you up”. RBS said that if a customer disputed the bank’s internal valuation, there would “ordinarily” be nothing to stop them getting the property surveyed independently. However, one email in the files reveals the bank’s auditors had flagged a further concern: Managers could “over-ride or ignore third party information (such as third party valuations)”.

At the same time, the files show, staff were under increasing pressure to find ways to hike customers’ interest rates. Chas Berwick, director of global banking and markets, wrote to managers to tell them it was “crucial” to find ways to charge business customers higher rates in 2008, because the credit crunch was forcing RBS itself to pay more to borrow from other banks. A sudden increase in interest could cripple a firm at a time of prevailing financial peril, and Berwick knew it. “It’s not easy to do,” he wrote. “We are asking customers to pay more – at a time when their businesses may be trading in the toughest conditions seen over the last 15 years!” But he warned: “This is the year of the Credit crunch, and in the current environment a Bank need [sic] to maintain a strong balance sheet for it’s [sic] very survival.” Berwick has since died.

Despite the best efforts of RBS managers, the dash for cash failed to stave off disaster. On 7 October, the bank’s chairman picked up the phone to the then chancellor of the exchequer, Alistair Darling, and told him RBS only had enough funds left to stay solvent for another two or three hours. The bank’s collapse threatened to capsize the whole nation’s finances, and the government had no choice but to come to the rescue. The exchequer pumped in £45 billion of public money in the biggest taxpayer-funded bailout in history, taking 83% of the bank into public ownership.

The near-collapse of RBS and the unprecedented public rescue package brought about the biggest overhaul in UK banking history. The government, which now effectively owned and controlled RBS, demanded that the bank scale back its risky asset exposures and increase the amount of cash it held as a buffer against potential losses in its reserves. The move was widely hailed as the right strategy to stabilise the bank and protect the taxpayer. But, the files reveal, it also helped create pressure for the bank to right its books by throwing its customers to the wolves – even if they had managed to withstand the economic crash without ever missing a single repayment on their loans.

Bosses spent the next 14 weeks “absolutely ripping the bank apart, understanding in detail what assets we’ve got, what are the risks we’ve got”, staff were later told in a speech by a top executive. In accounting terms, an asset is anything that is worth money – in RBS’s case, a mixture of its investments, its properties, and the loans it expected to be repaid. The more assets the bank could demonstrate it had, the more money it could borrow against them from other financial institutions in order to make new loans and investments.

But assets also carry risks, or “exposures", because their value may fall, and RBS’s total exposures had far outstripped its ability to cover losses as the economy crashed. Before the bailout, the amount of capital held in RBS’s reserves had shrunk to just 4% of its total asset exposures, which was how it had come so close to running out of cash as other banks and major investors rushed to withdraw their funds in the crunch. As a result of the post-crash overhaul, £258 billion of those asset exposures were designated “non-core” and slated to be offloaded.

On the newly condemned asset book were tens of billions of pounds’ worth of business loans RBS had made to British firms. Just like the bank itself, in order to borrow money, those businesses had to demonstrate that the assets they owned were worth enough to repay the money if required. With property prices in freefall, any business with a loan secured against real estate was likely to be deemed non-core. So were businesses operating in sectors that the bank considered risky in a recession – such as construction or leisure.

John Hourican, who became head of global banking and markets in the month of the bailout, explained the non-core disposal strategy in a talk to his staff in January 2009 that was secretly recorded and posted on the internet. The plan was, he assured them, “endorsed and agreed” by the government “in detail”. He personally had been to see the mandarins at UK Financial Investments, the body set up by the Treasury to manage taxpayers’ stakes in the bailed-out banks, to give a presentation “describing the strategy”, which he said was now “backed by our shareholder in detail”. But he acknowledged “it is somewhat difficult for some of the businesses where we have designated them as non-core”.

Now that the bank had identified which businesses it wanted to get out of, they were moved into a new non-core division. Hourican stressed that he had no further involvement with this division or any of its activities when contacted by BuzzFeed News last week, and said he had nothing whatsoever to do with GRG.

It was the job of the non-core division to devise a strategy to exit the businesses now under its control. It could run down the loan book gradually, waiting until lending agreements expired and then declining to renew them. It could sell the debts to other lenders at a sizeable discount. Or, if businesses could be found to be in loan default, they could be forced into restructuring. The bank could then make those companies accept a new loan with a much higher interest rate and heavy fees attached, or, even more drastically, order them to pay back the money all at once, compelling companies to surrender their most valuable assets. And that was where Derek Sach and his distressed-business empire came into the picture.

The dapper, snowy-haired executive had joined RBS from a private equity background and built its restructuring division from scratch during the recession of the early '90s. Now in his sixties, Sach was a veteran of debt restructuring, and GRG was his fiefdom. He had pioneered a new approach to distressed-business customers, using his private equity smarts to make sure the bank always got what he liked to call an “upside”. The restructuring division he built for RBS was a formidable profit-seeking machine, making gains in the form of massive cash fees, equity, and assets, and it was perfectly placed to squeeze as much value as possible out of the businesses RBS wanted to exit. Internal documents show that “non-core run-off” became one of his unit’s “top two priorities” in the years that followed.

More than 16,000 companies were pushed into GRG in the wake of the crash. They were worth £65 billion – vastly more than the entire public bailout package – and represented a massive chunk of the non-core portfolio the bank was hastily trying to dump. GRG managers sat on “watch committees” that picked out business customers for referral to the restructuring unit – and Sach had the authority to decide which firms GRG took into its control. Large numbers were transferred into the unit because managers said their properties were no longer worth enough to secure their loans, often on the basis of those internal fire-sale valuations that made the auditors uneasy. Almost any business with property was vulnerable. In went care homes, children’s centres, hotels, and farms in their hundreds.

The bank has always insisted that GRG dealt only with businesses that had run into distress. But the RBS Files reveal customers could be transferred into the unit without ever having defaulted on their loans or even breached any covenants. Companies could be pushed into the restructuring division just because of a “breakdown of customer relationship”. In fact, if a “customer litigates against the bank”, transfer was “mandatory”, according to an internal memo listing the “triggers” for referral to GRG.

Most startlingly, the trigger list reveals that if the customer came up with “any proposed exit strategy” – meaning they told the bank they wanted to take their business elsewhere – they could be pushed into restructuring.

The files reveal that one Lincolnshire care home business, United Health, was put into GRG “mostly due to strained relations”. The relationship had suffered because RBS had sold the company an interest rate hedging product as a condition of its loan – one of the notorious “swaps” that promised to protect businesses if rates went up, but generated crippling fees when rates plummeted after the financial crash. United Health had “threatened to take legal action against the bank in this regard”, the memo said, and that was why it was in GRG.

When contacted by BuzzFeed News, United Health’s chief executive, Philip Pearson, said he was “shocked” to learn that his firm had been put in GRG because of his complaints about the interest rate hedge. He said he had been told it was because the bank believed the value of his properties had dropped in the “weakening housing market” – meaning the company now had too much debt. After failing to refinance with another bank and refusing to accept harsher new terms, the company was transferred into GRG in 2011.

The unit wanted United Health to pay the loan back quickly and Pearson was forced to sell off three care homes. One was acquired by West Register for £1 million, while Pearson said he managed to sell the other two himself for £450,000 more than the bank had claimed they were worth. RBS said West Register was the highest bidder for the home it bought from United Health, and had sold the property on for a loss.

"Success story: full cash sweep with no funds returned to customer"

The care home business managed to escape from GRG after paying off the debt, but Pearson said he and his staff had to take big pay cuts as the business lost around £6 million in punitive restructuring charges and hedge costs. “We were a very weak company at the end of our time in GRG,” Pearson told BuzzFeed News. “It took us three to four years to build ourselves up again and cost us millions, but at least we got out. I don’t know if others would have been able to.”

The RBS insider who spoke to BuzzFeed News and the BBC on condition of anonymity said GRG could pluck any business it liked out of mainstream banking on the basis of “opinions” about its viability that he said were often “largely unsubstantiated”. “GRG would just get involved wherever they wanted to,” he said, and the crucial question that would decide whether a business went into GRG was: “Can they make any money out of it?” Once the unit had decided it wanted a business, “That was it – no discussion,” he said. But if GRG saw no way to profit from a distressed company, he said it would not be allowed in. “There’s other cases where you think, Christ, that should go into GRG, and they’re just not interested,” he said. RBS strongly denied this.

Internal financial records marked “secret” reveal the extent of the punitive restructuring fees and interest rate hikes GRG imposed on businesses as soon as they came into its clutches. Despite the bank’s public insistence that the unit never did anything to harm customers for its own gain, the records reveal that the extra sums it charged contributed hundreds of millions of pounds a year to the bank’s revenues.

Sach and his lieutenants were given regular updates on GRG’s revenues from these fees, “margin enhancements”, and “other upsides”, which vastly exceeded the unit’s costs. The packs contained a selection of “success stories” boasting of the biggest profits it had made off the backs of its struggling customers that quarter. In one such story, a property company that had been transferred because of a loan-to-value breach was charged fees totalling £485,000 and had its interest rate hiked from 1.2% to 4.5%. Meanwhile, it was forced to sell its properties, and restructuring managers used a “cash lock up mechanism” to ensure “full debt repayment", performing “a full cash sweep with no funds returned to customer”. In GRG, that was what success looked like.

The “profit and loss performance” packs listing these triumphs were sent all the way up to Nathan Bostock, the bank’s overall head of restructuring and risk, and Chris Sullivan, its corporate banking chief. Sullivan would later tell parliament “absolutely, unequivocally” that GRG was “not a profit centre”.

And the eye-watering fees that businesses were hit with on entry to the restructuring machine were just for starters. For many, the worst was yet to come.

The acquisition of property was at the heart of Sach’s plan to maximise his unit’s profits from the "non-core" run-off strategy, internal policy documents reveal, and the shrewd private equity man had built two investment arms to pick off customers’ assets in a classic pincer movement.

On one side was the Strategic Investment Group (SIG), poised to “work alongside” GRG “in the taking of equity and other upsides”, including property stakes, from businesses under its control. SIG’s portfolio expanded massively during the crisis, amassing “upsides” worth just shy of a billion pounds at GRG’s peak, according to secret financial documents.

On the other side, Sach had built up the bank’s own internal property division, West Register, which could swoop in and acquire customers’ properties when GRG forced them to sell up to repay their loans. This was particularly pleasing because it came with a double upside: both reducing the bank’s “material exposure to wholesale problem debt” – the “risky” real estate loans that had been deemed “non-core” – and allowing West Register to acquire prime properties on the cheap that could be flipped for a profit “via a future commercial sale in order to extract maximum economic value”.

After the crash, Sach geared up for a “rapid growth” in West Register’s activities. On 6 May, 2009, he wrote to staff informing them that extra resources were needed to support the massive expansion he anticipated in the division’s “buy-in activity”, and as such GRG had formed a “dedicated team” of real estate managers to “encompass activities from initial restructuring through to organising and managing the West Register buy-in”. Over the next four years, West Register’s public accounts show it multiplied its UK portfolio 22-fold. It amassed global properties valued at £3.3 billion before the market recovered and the great sell-off began.

Sach had spent more than 20 years building this GRG machine, and the documents reveal how he held sway over its every move. He sat at the head of the GRG management committee, which had the authority to decide which businesses were transferred into GRG and determined their fate once inside. Sitting alongside him were the heads of West Register and SIG, with their eyes on the assets of customers under GRG’s control. Special arrangements were made for the management committee members to be “above” Chinese walls put in place to prevent conflicts of interest arising in the acquisition of asset and property stakes from businesses in GRG, confidential minutes reveal. Sach also chaired the SIG committee that oversaw those deals, and he retained the authority to sign off the valuations of the asset and equity stakes they acquired. He controlled West Register’s strategic property committee, and he chaired the committee that approved its bids for customers’ assets valued at more than £5 million. Sach also sat on the executive committee that oversaw all GRG’s work, which was chaired by Bostock. And, despite multiple and potentially conflicting roles, Sach himself presided over the GRG risks and controls committee, which was responsible for policing potential conflicts of interest in the restructuring division.

All these positions gave Sach a level of power and influence that did not sit well with RBS’s external auditors. Deloitte warned the bank repeatedly about the “reputational risk” arising from Sach’s many roles. “Given that Derek sits in multiple committees within GRG he is able to influence the committee decision without much oversight from top management of the bank,” they warned in one meeting. Those warnings were not heeded.

The fate of businesses entering GRG was almost entirely under the control of Sach’s committees. The RBS Files reveal that these new entrants were divided into two camps – those considered worthy of “action” and those the bank wanted to “exit”.

The businesses in the “action” camp might be lucky enough to escape from GRG bloodied but unbowed – missing some assets or some equity, short a few hundred thousand pounds in fees, and paying more for their borrowing, but still alive.

But the thousands of businesses funnelled into the “exit” camp were almost all doomed from day one, because the bank was about to pull the plug on their loans. RBS has publicly maintained that GRG “successfully turned around” the “vast majority” of businesses that it worked with, but management documents classified “strictly private and confidential” reveal that in one six-month period, the bank “exited” 1,270 cases, while just 452 made it back to the main bank.

The “action” camp was for businesses that were “only in trouble for the short term” and could be returned to the mainstream bank after they were forced to shoulder loans with higher interest rates that were more lucrative for RBS. It was this group that SIG mostly targeted – demanding ownership stakes in the business itself or in property it owned in exchange for extended lending – in the expectation of future gains when the business returned to the main bank and continued trading. SIG had the power to threaten the cancellation of a customer’s loans if they refused to agree to the terms of the deal on the table – often giving the business owner no option but to accept or face ruin. “I had no experiences of the bank putting more money into an organisation without some nasty caveat,” the RBS insider told BuzzFeed News.

Andrew Gibbs, an award-winning Norwich architect, lost his business, all its assets, his home, and, he said, his marriage after refusing to give the bank a cut of the property he had developed into a communal space for local creative enterprises. When RBS first loaned Gibbs £1.3 million to finance the development in 2008, managers noted in internal emails that he was an “individual who has spent borrowed funds wisely and productively thus far and has a good track record with the bank”. Even so, they made it a condition of the loan that he buy one of the infamous interest rate hedging products that quickly became cripplingly expensive when rates were slashed after the crash.

Just one year after getting that loan, his design firm was thrown into GRG after the bank claimed it was in loan-to-value breach. In a letter notifying him of the move, the bank assured Gibbs that GRG would aim to “return the business to a cash positive position”. But after a mere nine days, GRG took control of the firm’s accounts and, Gibbs says, started cancelling essential direct debits. He emailed the bank to express alarm that it had stopped his payments for professional indemnity insurance, which is a legal requirement to practise as an architect. Then, he said, it cancelled his business tax payments and even told Norwich council he had died. “They threatened my professional life,” the architect told BuzzFeed News. The bank said it had no record of stopping his professional indemnity payments or telling the council he was dead, though it acknowledged it routinely cancelled direct debits when recovering customers’ debts.

Gibbs insists that his business was in good order. Its financial records show the architect had work worth £720,600 already lined up for the following year, and there had been no drop in the rental receipts from tenants in his development. The bank disagreed, and it was prepared to crush his business if he wouldn’t accede to its demands.

On 23 October 2009, Gibbs got a letter out of the blue demanding immediate repayment of his entire loan. But in a separate email the same day, GRG offered to re-lend him the money, with an extra £400,000 on top, if he handed over a 15% stake in his prized property development. Gibbs was dismayed and unwilling to be held over a barrel, so he refused. A week before Christmas, RBS called in the administrators, and within months the architect had been evicted from his development. He sold his family home in a desperate attempt to save the business, but failed to fetch enough to see off the administrators. Soon after, his development was sold to repay the bank.

“They almost strip away your clothes and put you into the corner. Mentally they are just hitting you all the time”

Within a year of this “good” customer being sucked into GRG, he had lost everything.

“When I fell, the fall was really big,” Gibbs told BuzzFeed News. He said that he suffered a mental breakdown and that his marriage ended as a result of his involvement with GRG. “They almost strip away your clothes and put you into the corner,” he said. “Mentally they are just hitting you all the time.”

It wasn’t just property stakes that the SIG team demanded in exchange for continued lending – the investment arm could also demand cheap shares in a customer’s business under threat of pulling the plug on its loan if they refused. The files show RBS’s auditors had concerns about this aspect of GRG’s operation. They warned that there was a “significant risk” in the “valuation and accounting treatment” of the equity stakes SIG took control of, one internal memo shows, because the bank got its share of a customer’s business at a “distressed or negligible value”. SIG stood to profit on subsequent increases in the worth of the equity it obtained, but RBS has insisted that no valuation was ever manipulated. The investment group’s own policy manual acknowledged a “potential for conflict of interest” inherent in this arrangement – but instructed staff to keep it under wraps. “The SIG deal member will have a focus on ensuring that the best possible terms and conditions are negotiated with regard to the equity stake and these can, occasionally, conflict with the GRG debt RMs [relationship manager’s] objectives,” it noted. “Any issues should be resolved professionally and not in front of the customer or other lenders and stakeholders.”

That was the way GRG treated the customers it had deemed “viable” – the ones it had slated for “action”. The “exit” camp, on the other hand, was for businesses it wanted to dump straight away. These were companies that “may not be in receivership but RBS believes it may be headed that way or there are other risks attached”, a GRG process memo in the files stated. On the basis of that supposition, GRG managers were instructed to pull the plug on their loans, demanding that the customer “repay the debt as soon as possible”. Once that decision had been taken, GRG managers had the power to block a company’s access to new funds, making it impossible to pay suppliers or other creditors, including the tax authorities. They could cancel overdraft facilities and credit cards without notice. They could seize every penny of the company’s cash held in RBS accounts.

"There will be potential for conflict of interest ... Any issues should be resolved professionally and not in front of the customer or other lenders and stakeholders"

And, ultimately, they could push the business into insolvency and force the customer to sell off its assets. That was when West Register stepped in.

The bank’s public position is that when an asset was being sold to pay down a customer’s debt to RBS, the bank acted only as a “bidder of last resort” in cases where there were no other viable buyers. But a document describing the control structure of GRG declared: “West Register is mandated to consider purchasing any property asset where the property loan is distressed and where the property is being offered for sale.” The division was “particularly interested in assets where there is potential to increase value”, the controls document said, and “the only assets West Register will not consider are those valued below £250,000”.

RBS has also insisted that strict Chinese walls stopped any conflicts of interests arising when West Register set its sights on the assets of troubled businesses supposedly receiving “intensive care” in GRG. As a “general rule”, the property division’s policy and procedures manual stated, if there were other lenders with debt to recover from a sale, West Register “should be provided with no more information about the charged assets than any other bidders”. But then the manual went on to apparently contradict itself. As long as the loan documents were in “bank standard format”, there was “no confidentiality obligation owed to the customer which would restrict disclosure of information to WR,” it said. That meant that GRG managers could disclose information about the customer’s “debt and security package” as well as “any defects or downsides” affecting the property, “even if these are not being disclosed to other bidders”.

If there were no other lenders in the mix, West Register’s path to acquisition was even clearer. Then, the policy manual stated, “a more pragmatic line can be taken and GRG may share information about the charged assets” without any restrictions. What’s more, in these cases, it wasn’t even necessary to open the bidding to others, which, of course, might have given the customer a better price for its assets. The manual stated that where there were no other lenders in the mix, “a full marketing process is not required”.

RBS said this part of the policy only referred to occasions when the customer was prepared to agree to a deal with West Register. But the Clifford Chance report had flagged concerns about what GRG called “consensual sales” by its “distressed” customers to its own property arm – warning that they could be deemed “unfair” given that the bank “has additional leverage in any negotiation” because it controlled the seller’s loans and bank accounts.

In the event that West Register did have to go up against other bidders in an auction, the policy document shows, the bank’s property division would be given a helping hand. The manual states West Register “should bid blind for a property with no knowledge of external bids” in order to “ensure the bank cannot be accused of self-dealing”. But it also reveals that GRG managers were given “indicative bids” from other potential buyers in advance of an auction, and they were instructed to give West Register “guidance” on whether its bid was likely to be “acceptable”. West Register would only be allowed to bid once, so the private advice helped to make sure it could pitch the price right on the night. The bank’s property arm was focused on acquiring properties at a low enough value to make a tidy profit on their resale, so if it knew an asset was going to sell cheap and bumped up its planned bid a bit to be sure to pip the competition, it could still get a great bargain. If, on the other hand, a property was more likely to sell for closer to its fair value, and West Register didn’t want to pay that price, it would still submit “underpinning” bids to ensure no one else got too much of a bargain. Either way, RBS won.

Clifford Chance would later argue that the bank got no advantage from acquiring customers’ assets cheaply when they were sold to pay back a debt because “any gain to West Register will be offset by a corresponding under-recovery on the customer’s loan”. But this statement overlooked the future capital gain West Register stood to make when the assets were resold, as well as GRG’s power to perform a “full cash sweep” of the business to recover the rest of its money. RBS said West Register only acquired 20% of the properties it bid for – though the files suggest 34% of its bids were successful in 2012 – and said it had only been able to resell a handful of properties for more than the original loan had been worth.

And the documents reveal Sach’s unit had another major incentive, beyond turning a profit, to tip customers’ property assets out of the bank’s loan book and into West Register.

In the wake of the crash, new global banking rules had increased the amount of capital banks were required to hold in reserve as a buffer against potential losses on risky assets – and property loans carried a particularly high “risk weighting”. So for almost every business whose loan was secured against property, the bank had to freeze a whole load of cash in order to satisfy the regulators it could cope in the event of a default. This regulatory capital was effectively dead money that the bank could not invest elsewhere – a serious impediment to trade.

But by demanding repayment of property loans, the bank not only recovered the money it had lent, it also got back a lot of the capital it was having to hold in reserve. That was a big double win for GRG, because freeing up this regulatory capital was one of the most important metrics by which its success was measured after the crash, secret financial documents show. After the bailout, more than 500 GRG relationship managers were trained to calculate “the capital impacts of restructures”, figuring out how they could release as much regulatory capital as possible as they took decisions about a business’s future. And that was how many firms with property loans found themselves being forced to sell up to repay the bank.

By going on to acquire those properties for West Register, the bank converted what had been risky loan exposures tying up regulatory capital to valuable owned assets that it could resell later at a profit.

RBS still had to retain some capital against properties that it owned, so GRG deployed accounting wizardry to minimise that burden. Instead of the bank itself holding these properties, GRG had set up a network of “special purpose” subsidiaries under the West Register umbrella to hold them, and classified them as “ancillary”. Even though RBS had purchased the properties and ultimately controlled their fate, this manoeuvre allowed the bank to keep these properties off its main balance sheet and cut down the amount of capital it was required by regulators to hold as a buffer against losses.

Sach’s strategy was as masterful as it was multifaceted, and it paid off big time. By 2011 GRG had reached the peak of its powers, racking up profits of £1.2 billion in that year alone. West Register and SIG acquired combined owned assets worth more than £4 billion, and financial documents classified “secret” reveal that on top of those material gains, GRG offloaded enough risk-weighted assets to free up tens of billions of pounds of core capital from the bank’s reserves.

But even as the bank celebrated GRG’s most profitable year yet, Sach’s masterplan began, slowly, to unravel.

In the summer of 2011, City regulators from the Financial Services Authority (FSA) paid GRG a visit. They were there to review the way the unit made credit decisions and provided for losses, and while they found it “fit for purpose”, there were aspects of what they saw that caused them concern.

The regulator wrote to Sach flagging concerns about the “rapid growth of GRG’s business” and warning about the “reputational risks” involved in acquiring assets from its customers, particularly in light of the “increase in scale envisaged for West Register and SIG”.

Then, the files reveal, the regulator turned its spotlight on how the assets West Register had acquired from GRG’s customers had been squirrelled away in the special purpose vehicles outside the main bank. This caused real problems. The bank had classified the West Register properties “ancillary”, minimising the amount of regulatory capital it had to hold against them – but the FSA was not having any of it it. In mid-2012, the regulator stripped those assets of their ancillary status, ruling that they were “connected” to the main bank and more than tripling the amount of capital RBS had to freeze against them to 25% of their total value.

This all came to a head in a July 2012 meeting of a key committee chaired by Sullivan, RBS’s head of corporate banking, in charge of overseeing the run-off of “non-core” assets. At the meeting, Declan Hourican, GRG’s chief finance officer (and John Hourican's brother), warned that “regulatory scrutiny of GRG had intensified”, according to the confidential minutes. He explained that the “FSA [was] taking a punitive view on the capital treatment of West Register and owned assets which will have an adverse effect on the business model and capital held for owned assets”. If RBS had to transfer the West Register portfolio to the bank’s main balance sheet, then, he warned, “significant administrative, legal and tax costs would be incurred”. Hourican did not respond to a request for comment.

A document reviewing GRG’s budget the following year revealed that this and other tough regulatory moves had resulted in “£10 billion of regulatory headwinds” for the bank.

This crushing ruling heralded the start of the great West Register sell-off. Its property portfolio in the UK had ballooned exponentially since 2008 and was now more than 22 times bigger than it had been at the time of the government bailout. But after the FSA’s intervention, financial documents show that the portfolio began to shrink for the first time since the crash, diminishing by £167 million over the next two years as the bank started selling up. RBS said its decision to sell off West Register’s portfolio was not prompted by capital requirements.

In the wake of the FSA’s ruling, the files show Sach drafted a paper announcing that West Register had set up a new real estate asset management team to hunt for ways to profit off customers’ assets in a variety of ways beyond just taking ownership. The paper acknowledged the plan gave rise to “a range of legal, regulatory and operational related risks”. The new real estate team would guide GRG managers on which assets should be sold and when, and then help “develop a mutually agreeable sales strategy”. They would also work with insolvency practitioners to “maximise the Bank’s recovery” as well as continue to formulate bids on behalf of West Register. It was classic Sach strategy – designed to strengthen the bank’s position at every stage.

But by now Sach’s operations were coming under increasingly uncomfortable scrutiny from RBS’s own external auditors, the files reveal. In an October 2012 letter to a risk and audit committee chaired by Sullivan, Deloitte warned that Sach’s multiple controlling roles in GRG and West Register “could create the perception that the Chinese Walls are not fully robust”. They also noted that “the current business model whereby RBS originates property loans and in certain instances purchases the underlying properties, gives rise to the potential reputational risk of a perceived conflict of interest”. The bank said it took steps to minimise such conflicts of interest in early 2013.

By the autumn of that year, RBS was embroiled in a scandal over its mis-selling of the interest-rate hedging products that had crippled many business customers, and it was facing increasingly angry complaints that it was hampering the economic recovery by its reluctance to lend money to help launch new businesses. The bank had appointed the former deputy governor of the Bank of England Sir Andrew Large to conduct a review of its lending practices towards small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and Large published a critical report on 1 November 2013, chastising RBS for being “unwilling to lend” and calling for a complete overhaul of its policy on business loans.

The report’s topline finding made headlines, but buried in the detail, and largely overlooked by the media, was the first public hint of the rot in RBS’s troubled business division. Way down on page 52, Large noted that there was “perceived conflict of interest” within GRG and he had come across some claims that it “may even be profiting by working against the best interests of financially distressed customers”.

He warned that “RBS’s governance structures do not do enough to address the potential conflict of interest”, in large part because “GRG is run as an ‘internal profit centre'". It was not part of Large’s remit to get to the bottom of whether the allegations were true, but he recommended that they be investigated fully.

Lawrence Tomlinson published an explosive report in 2013 accusing taxpayer-owned Royal Bank of Scotland of destroying healthy businesses for profit.

Three weeks after the release of the Large report, journalists at the Sunday Times, including one of the authors of this article, published an investigation revealing that dozens of small businesses had been forced into insolvency by GRG and had their assets snapped up by West Register. The day after that, Lawrence Tomlinson, an enterprise adviser at the Department for Business, who had been conducting his own review of the big banks’ treatment of small businesses, published a report that created a firestorm of censure for RBS.

Tomlinson had gathered evidence from hundreds of small firms that he said had experienced “heavy handed, profiteering and abhorrent behaviour” by GRG. He had observed a pattern: “The bank artificially distresses an otherwise viable business and through their actions puts them on a journey towards administration, receivership and liquidation.” The business secretary, the chancellor of the exchequer, and the governor of the Bank of England all demanded an urgent regulatory investigation. Within a day of the report being published, the Financial Conduct Authority had launched an official inquiry.

But RBS fought back vociferously, denying Tomlinson’s allegations in their entirety, claiming his report contained “no evidence” and insisting that “GRG successfully turns around most of the businesses it works with” and “helps businesses back to health”. It vowed to clear its name and paid Clifford Chance – which had often advised GRG – to conduct an “independent investigation”.

The headline finding was everything the bank could have hoped for. When the law firm finished its work in April 2014, it announced it had found “no evidence” of an institutional and systemic effort to harm small businesses for profit. “RBS cleared of forcing clients into insolvency to buy up assets” ran the headline in The Guardian. Though buried in the detail of the report were a number of criticisms of GRG’s behaviour – including its failure to adhere to independent valuation standards, its use of threats to force customers to hand over equity, and its inexplicable fee structures – the overall effect was to exonerate RBS. Clifford Chance told BuzzFeed News it was “confident in its findings”. On the back of the report, the new RBS chief executive, Ross McEwan, did a victory lap of media interviews welcoming the report and praising the work of GRG. “Our independent report said this was a pretty good unit,” he said in one radio phone-in. Thus emboldened, the bank announced that it was considering suing Tomlinson.

But the respite from controversy did not last long. Two months later, Sach and Sullivan were hauled before the Treasury select committee for a grilling by MPs.

Until now, Sach had remained silent about the activities of his unit, staying firmly in the background as McEwan and the bank’s public relations outfit fought the fire. Now, sitting in front of the parliamentary inquisitors, the GRG mastermind looked strangely diminished in silver-rimmed spectacles and a wide-lapelled jacket just a little too big for him. He took his place next to Sullivan on the green chairs in the airless committee room, hunching slightly forward so his jacket bunched around his shoulders, and the politicians opened fire.

For starters, Andrew Tyrie, the committee chair, took aim at the Clifford Chance report. “You have described that as independent. Doesn’t Clifford Chance do business for RBS, other business?” Sach had to admit: “Yes, we do business with all the large corporate lawyers." Then the MPs wanted to know how many drafts of the report had been submitted to RBS before it was published, and whether they had been interfered with. “I have no idea,” said Sullivan. “I never saw a single draft.” That was an answer that would come back to haunt him.

Next, the MPs cut to heart of GRG’s practices. “You have been with GRG for a long time, Mr Sach,” said John Mann. “How much has it contributed to the bank’s profits?”

Sach’s answer was unequivocal: “It does not contribute to the bank’s profits at all,” he said. “Our main objective is to restore the customers’ health and strength.” Sullivan backed him up. “It is absolutely not a profit centre,” he said, adding that it would be “totally inappropriate” to describe it as such.

The MPs were incredulous, pointing out the finding in the Large report that GRG operated as an “internal profit centre”. Digging in, the two executives ventured that the former deputy governor of the Bank of England had been mistaken.

“So he just got it wrong?” asked Tyrie.

“I believe so, yes,” said Sach.

Another committee member, Jesse Norman, chimed in. “Just to be clear: Andrew Large, banker for 20 years, chairman of the Securities Investment Board, member of the management board of the Swiss Bank Corporation, deputy chairman of Barclays Bank, Bank of England monetary policy committee member; you would expect him to know what a profit centre and a cost centre of a bank was, right?”

“Yes,” Sach said, he would. But he maintained that Large’s description of his unit as a profit centre was “not logical”.

Norman pressed him further. “You entirely discount the possibility that he might understand the true function of business better than you are prepared to admit?”

“Yes,” the restructuring boss maintained. “I am not trying to cover anything up.”

"It does not contribute to the bank’s profits at all. Our main objective is to restore the customers’ health and strength"

Sach and Sullivan repeated their insistence that GRG was not a profit centre no fewer than 27 times during the hearing. But today, the RBS Files leave no doubt about the hollowness of those claims. Both men received detailed updates on the unit’s “profit and loss performance” every quarter. They knew well that since the financial crash, it had contributed hundreds of millions every year in fees, fines, and upsides to the bank’s bottom line.

After the hearing, Tyrie wrote to Large to ask whether the former central banker had indeed been wrong to identify GRG as a profit centre. “I was surprised by some of the evidence given by RBS to your Committee," Large responded, coolly. “I am confident that the terminology used in my Report is appropriate." He derived his confidence from the fact that the description of GRG as an “internal profit centre” had been “employed in correspondence to us by senior members of GRG and were at no point objected to by RBS, despite a governance process established to ensure factual accuracy.”

That forced RBS into a humiliating climbdown. Its chairman, Sir Philip Hampton, wrote to Tyrie, admitting that “the evidence that the bank’s representatives provided was not correct in answering the question as to whether GRG was a profit centre”. He apologised for this “lack of clarity on an important point”, but he said Sach and Sullivan had made “an honest mistake”.

As it turned out, Sullivan had made more than one such error. He wrote to the committee to admit that he had, in fact, reviewed an early copy of the Clifford Chance report before it was published, despite telling MPs “I never saw a single draft”.

That was when RBS announced that GRG would be shut down. Sach was leaving the bank, along with the head of West Register, Aubrey Adams. A few months later, it was announced that Sullivan, too, was leaving before the end of his contract. He found work again as the head of small business at Santander, where he remains today, having been recruited by the bank’s new chief executive, Nathan Bostock – the former head of restructuring and risk at RBS, who oversaw the work of GRG. The ravens had left the tower, and RBS’s kingdom of troubled business had finally fallen.

But across the country, men and women who lost their livelihoods after businesses were killed and their assets swept into West Register are still waiting for answers. And up to now, the government's watchdog still hasn't bitten or even barked. The FCA’s investigation was due to conclude in 2014, but has been repeatedly delayed. Last week the regulator released its latest update, announcing that the report was now complete, but that there remained a “number of steps for the FCA to complete before we are in a position to share our final findings”. It is unclear when the findings of that investigation will be published.

RBS told BuzzFeed News that “despite a number of investigations that involved a detailed review of all the evidence”, it had “seen nothing to support the allegations that the bank artificially distressed otherwise viable SME businesses or deliberately caused them to fail”, or that it bought their assets at a lower than market price. It said it could not comment further on its treatment of small businesses until the FCA’s review had finished.

McEwan, the new CEO, brought in to clean up after a slew of scandals, has put supporting small firms at the heart of his plan to rebrand RBS as “the bank that earns your trust”. But he has also staunchly defended GRG, even saying in a speech last year that for “many” customers, going into the restructuring unit was “the best experience of banking they ever had in their life”.

Only in the light of the RBS Files has the bank finally changed its tune. “In the aftermath of the financial crisis we did not always meet our own high standards and we let some of our SME customers down,” it said in a statement.

“These were incredibly difficult times for the bank and the wider economy,” it continued. “The bank itself was in a precarious position and required extensive Government support.

“Since that time, RBS has become a different bank and significant structural and cultural changes have been put in place, including in how we deal with customers in financial distress. We continue to learn the lessons of the past and seek to do better for our customers.”

Too little too late, say many business owners who saw their firms decimated in GRG. Hundreds have now taken matters into their own hands and are gearing up to sue RBS in a multibillion-pound group action over their treatment in GRG next year. The organisation running the group action – RGL – said the number of businesses involved will “certainly exceed 1,000” and they believe the claim is worth “in excess of £7 billion”. For many of the entrepreneurs signing up to join that action, the ramifications of GRG’s heavy-handed treatment are still unfolding. Among them is Kenny Riddoch, an Aberdeenshire farmer who was made homeless along with his wife and four small children this summer.

Riddoch was pushed into GRG in 2008 after asking for more money to finish a property development. The bank gave him some extra finance, but then GRG hiked his interest rates and, he said, hit him with monthly fees of £10,000. Riddoch struggled through five years in the unit, fighting to save the business by selling off thousands of livestock to keep up with charges that he said spiralled into millions of pounds and starved his business of cash. The bank said GRG’s fees were limited and added to Riddoch’s debt rather than ever being paid. But GRG finally pulled the plug on his loan in 2013 and sent in the administrators to seize his land and all his properties.

But Riddoch clung on, refusing to leave his farm for three years until, this summer, he and family were finally forcibly evicted. Now the administrators are pursuing him for £176,000 in backdated rent they say he owes the bank for continuing to live on his farm. Only last week, RBS got an order to freeze all of Riddoch’s bank accounts. The farmer said he and his wife are now unsure how they will feed their family through the winter.

“GRG’s involvement in my business and my family has had a huge impact,” he told BuzzFeed News. “It's taken everything away, and there’s nothing left.” ●