If you’re the kind of person whose late-night internet search history would sound bad if read aloud at a tribunal, you probably found Caitlin Doughty’s YouTube series Ask a Mortician by accident.

Whether you want to know if you can compost a dead body (yes), if you can send your friend off in a Viking funeral (illegal but fun), or if caskets explode from a build-up of putrefaction gas (oh, sure), you can just send your questions to Caitlin and she’ll answer them straight up, no bullshit.

I wanted to know about dying and the internet, DIY funerals, and how we do death differently now that we’re in the future.

Are we doing death differently now in 2015 than we were 20 years ago?

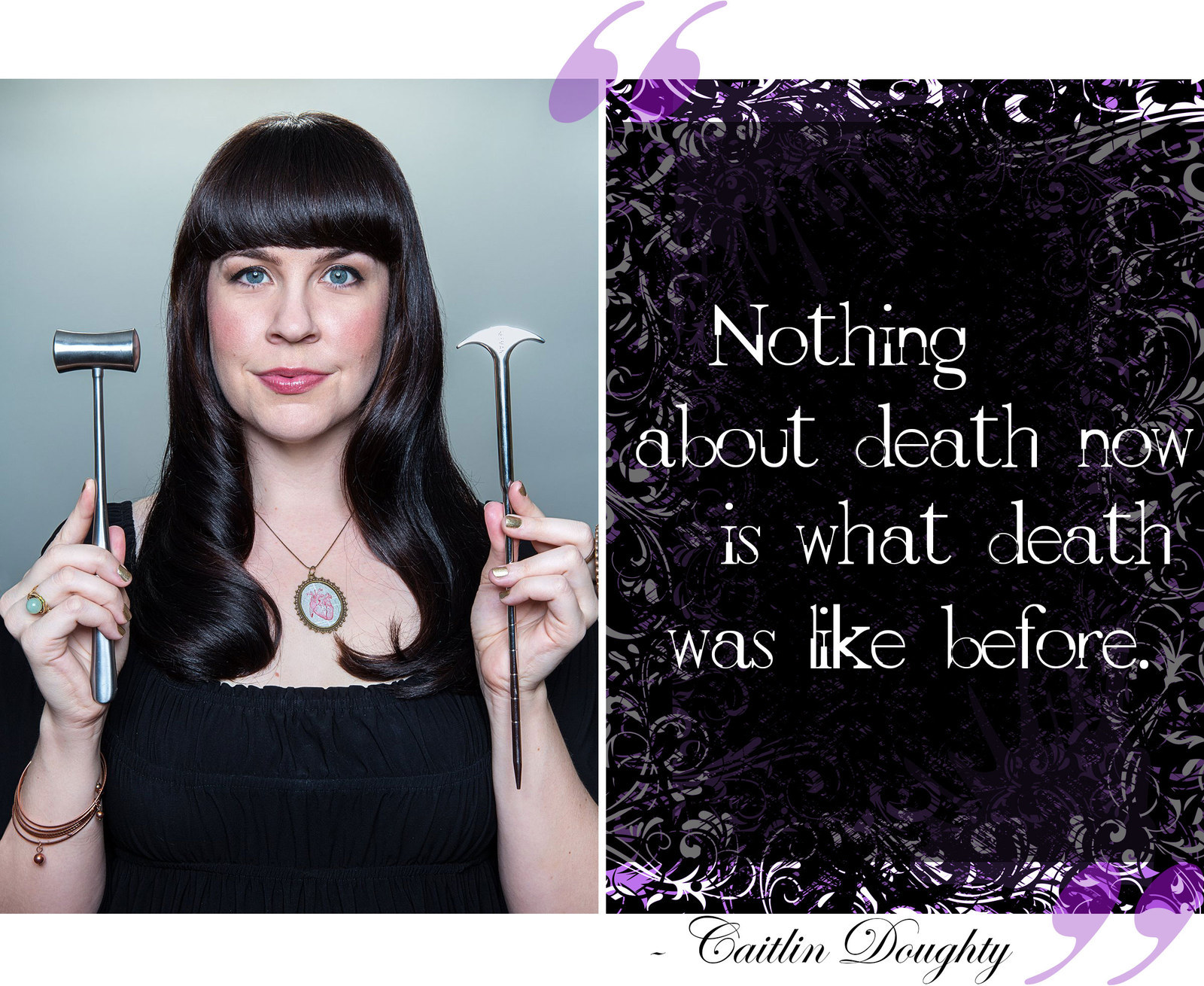

Caitlin Doughty: Death is different in many ways. People tend to only recognise their immediate surroundings as in, like, “Oh, this is the way death has always been done so we have to do it this way.” But nothing about death now is what death was like before.

“Before,” like, two decades ago?

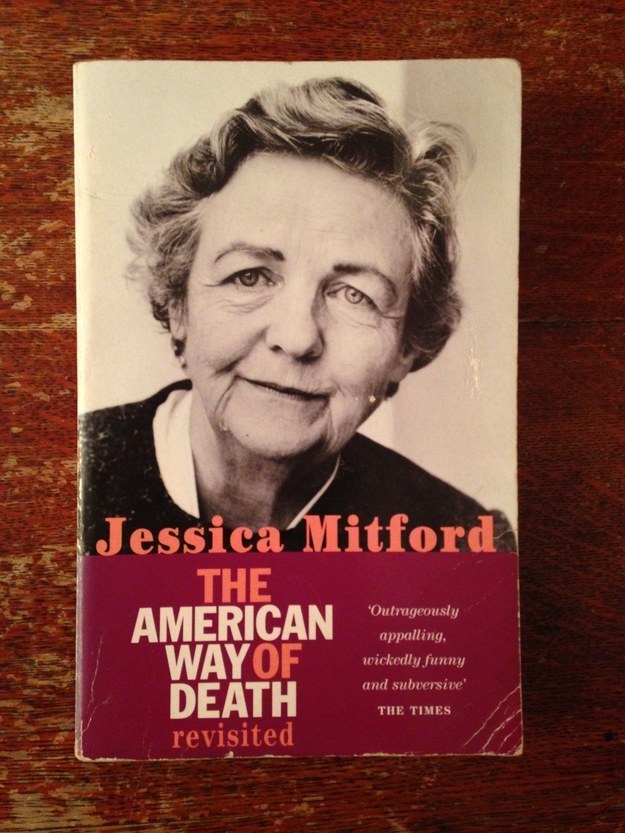

CD: Before as in two decades ago, 50 years ago, 100 years ago. In every country, death culture and death ritual is constantly evolving. So when you think about what’s happening in the US and the UK in the last 20 years, there’s been a huge rise in cremation. In the US it was actually partly due to the AIDS epidemic, and Jessica Mitford in the '60s who came in and said that funeral directors were crooks, they’re taking you for a ride, you don’t need any of these things.

I love her book.

The American Way of Death: an exposé published in 1963 about the highly commercialised American funeral industry that’s actually way funnier than you think it’s gonna be.

CD: Yeah, it’s very sassy. And it really brought about a huge rise in not only direct cremation — cheaper, no pomp, no ceremony — but also body donation, because people wanted to get around the funeral industry in some way. And people have now done that. They know that they can choose not to view the embalmed body and they don’t need to pay for any of the things the funeral directors provide — the fancy cortege, the fancy plumes down the street — they can just cremate the body, have a memorial service if they want, and that’s it.

So now we’ve got to peak industry avoidance, or peak ways-to-get-around-the-industry. And where the “natural death” or “death acceptance” movement comes in is saying: But do you feel like you’re missing something? Don’t you feel like you’re missing something about the rituals, or you’re missing something by the body disappearing and you never seeing it again? And a lot of people do feel that way.

So more people are choosing DIY funerals?

CD: It’s not like people are rushing out to take care of the dead body themselves, or they’re rushing out for natural burial, or they’re rushing out for alkaline hydrolysis machines. There’s not a flood, just because you don’t think about it until somebody dies. It’s not in the popular consciousness.

What the hell is alkaline hydrolysis?

CD: I definitely think it’s the next death technology. They’re billing it as water cremation, which is not really accurate because cremation is inherently flames, but they’re billing it as that because it’s a similar system. There’s a big metal receptacle that the body goes in, and really high-pressure, high-heat water — 160 degrees Celsius — and the base chemical lye go in together, and it’s almost like a flash decomposition. It breaks the body down to its basic elements, and what you get at the end is really similar to cremated remains: a white powdery substance.

Alkaline hydrolysis machines seen in Quebec (top left) and Ontario (top right) by Bio-Response Solutions.

Is it better for the environment?

CD: Yes, because you’re not releasing carbon emissions, you’re not using a ton of natural gas to make it happen, and it’s certainly better than burial, where you’re sometimes chemically treating the body, and you have the wood for the casket, or the metal for the casket, and the concrete for the vaults, and you’re using up land. It’s only legal in eight states in the US, and not at all in the UK, which is bullshit and stupid.

There’s a guy in Minnesota with an alkaline hydrolysis machine who asks people, “Which cremation do you want: Do you want it by flame or do you want it by water?” – and something like 80% choose water. I think it’s going to do well in the death landscape.

When is a natural burial (the kind where you go straight into a hole in the ground, not a cement box above ground) or a DIY funeral going to become our default setting?

CD: We’re playing the long game. In 20 years, people our age and people slightly older than us will have heard this discourse in culture and they’re gonna say, “But I’ve always just thought I wanted a green burial” or “I’ve always thought that I want my family to take care of my body” and it will seem a lot more natural to them because they’ve heard it for so long. That’s what I think the future is, but that might just be my own bias.

What’s the process of DIY funeral? What do the family go through?

CD: You have the body at home for two days, three days, however long it takes for the family to sit with it and for it to feel done. You wash and dress the person yourself, and you observe the little changes in their body. Their eyes start to sink, you can feel them go to room temperature, you can feel the stiffening up and then the loosening, and you just know that the person you love isn’t there anymore. Then you take that shell of the person and you go ideally to a natural burial cemetery, or you go to a crematorium and you actually load the body into the machine.

What kind of feedback have you got from people who’ve done it?

CD: They’re not cool with the death – they’re not like, “Y’know, and then I just grieved over those three days and I never missed Jimmy again.” That’s not what happens. But I’ve never heard someone say, “Yeah, I took care of my own mother and it was really gross and uncomfortable and I wish I hadn’t done it.”

How do you even start to do a DIY funeral?

CD: The death midwife will come to the house and help figure out the logistical things like the best place to keep the body and how you’re going to move the body. They make sure they have all the things they need, like dry ice or diapers. They ask questions like how do they want the eyes and mouth closed — totally naturally, or do they want a little help?

What’s a death midwife?

CD: They’re women who come in, who are not in the funeral industry, and they help you take care of the dead body in your home outside of the funeral industry.

Why is it always women?

CD: It’s a much more interactive-with-the-body kind of funeral work. My personal theory is that it has to do with wanting control of the body, whether it’s control of your sexuality, whether it’s control of childbearing, or control of the dead body, we’ve had control wrested away from us of our own physical selves, and it’s almost like a feminist act to say, “No, I want control of all parts of life and death that have to do with the body,” so that’s where I think it comes from.

This natural death movement isn’t a new idea; there was one in the ’70s. Was it very different to now? And why did it go away?

CD: It is a strangely largely forgotten phenomenon. I think it wasn’t so much the actual dead body as it was the process of dying — the power to die, the power to make health care decisions, the power to end life-saving medical intervention or food or whatever it was. To die on your own terms. But it was a period of what they called “death awareness” in the UK and US. Medically, people are back around it again, and they’re asking how far have we really come, and how good are we at dying the way we want to. Most people would say we aren’t good at dying the way we want to.

Where does assisted suicide fit into this?

CD: I work with a group called Compassion & Choices in California. It’s attempting to get death with dignity legalised in California, the idea being that so goes California, so goes the rest of the US at least. That’s one of the most fascinating things to me — is how important control is to people and how few people actually take the pills or the liquid or whatever they are prescribed by the doctor, but they feel much better, they feel, just to have the option. So if you’re dying of stage 4 cancer but you have that stuff in your fridge, you know it’s there and you know that if this pain ever becomes blindingly unbearable you have a dignified out to take. When you have that kind of control and that security, you live longer. Mentally it’s so important for people to have that.

That’s another future death thing, in where we’re going with death in general, is towards more control. Taking control of our lives and death back from the government, from industries — from the medical industry, the food industry, the funeral industry — and taking it back to the family and the individual.

Since we both live on it, I want to know how you think we should die on the internet. I worry about this a lot.

CD: I think it’s important that, just like you tell people you want done with your body, you tell people what you want done with your online life. Maybe you just want all your accounts deleted. That may not be the nicest thing to do, but you’re allowed to be an asshole.

Burn mine to the ground, please.

CD: I really love Terry Pratchett’s last tweets. I haven’t done it yet but I really do need to tell somebody who has my Twitter password, “If I die unexpectedly, here are three epic bons mots.”

Exactly. Otherwise it’s just going to be whatever you last said. Leonard Nimoy had a great last poetic tweet, but if it’s me, it’s probably going to be raging at Sainsbury's because they’re out of avocados or whatever.

CD: Right. They’re the kind of things that go viral if it was an interesting death or you’re an interesting person of some sort. If I were to die unexpectedly, I need something in place like, “She died doing what she loved: death” or, y’know, “All she needed to do to die doing what she loved was just die.” Something like that. I think it’s a good idea to have people ready for it. I have two people who have all of my passwords.

Already?

CD: Oh yeah, never too early. Treat your online affairs as part of your affairs that need to be in order — your bank, your internet bill — you need to have people who know what you want.

Here are Terry Pratchett’s final tweets:

AT LAST, SIR TERRY, WE MUST WALK TOGETHER.

Terry took Death’s arm and followed him through the doors and on to the black desert under the endless night.

The End.

And Leonard Nimoy’s:

A life is like a garden. Perfect moments can be had, but not preserved, except in memory. LLAP

And what is probably the closest approximation of what I will ultimately leave as my final tweet:

If I ever see a longer pair of balls than the pair I've just seen on Sylvester Stallone I will let you know, twitter.

IN CLOSING: Listen to Caitlin, get your internet death together ASAP.

Caitlin Doughty’s New York Times best-selling memoir Smoke Gets in Your Eyes is now out in the UK in paperback. Follow her on Twitter.