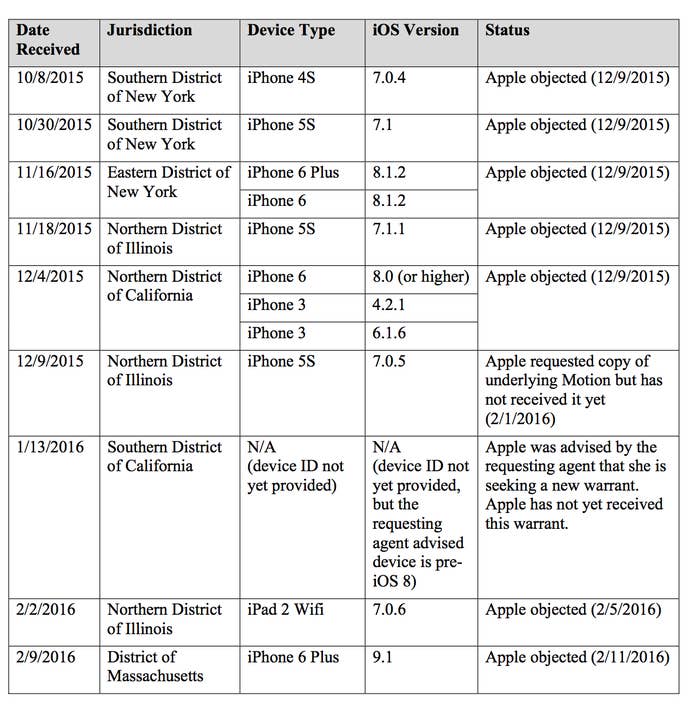

Last week, a federal judge in New York instructed Apple to provide a list of current cases where the government seeks to extract information from password-protected iPhones. That list was unsealed by the court Tuesday, revealing that in several cases around the United States — including New York, Illinois, California, and Massachusetts — the government seeks to compel Apple to help pull data from 12 different iPhones and iPads.

The list, compiled by Apple and reviewed by the Justice Department, details other active cases in which the government’s requests for Apple’s technical assistance were similar to that of a New York case, involving an encrypted iPhone and a person suspected of distributing methamphetamine. For each of the 12 iPhones, the government invoked the authority of the All Writs Act, in order to force Apple to bypass security features built into the devices.

Apple also points to the locked iPhone of Syed Rizwan Farook and the investigation into the mass shooting in San Bernardino that left 14 people dead. In that case, which has generated a national controversy, the government demanded that Apple design new software that would help unlock an encrypted iPhone by disabling several security tools.

Apple and its allies have described the court order in San Bernardino as amounting to government coercion. They have argued that the government has taken an unprecedented step, asking the company to manufacture an encryption backdoor that would weaken the security of not just one iPhone, but all of them. Apple insists the the "FBiOS" would hypothetically work on other iPhones.

(Four of the twelve iPhones at issue run on iOS 8 or above. And, according to Apple, these more current operating systems prevent the company from simply extracting information from encrypted iPhones, which, at the request of the government, it has done in the past.)

In response to the list of 12 iPhones under government search, the Justice Department took exception with Apple’s characterisation of the status of several cases. The list includes the jurisdiction of each search request, the model and iOS, and Apple’s response. But the government argued that “Apple’s position has been inconsistent at best.”

In several cases, Apple stated that the company objected to the search of the phones. The government, however, insists that this is “misleading.”

“Apple did not file objections to any of the orders, seek an opportunity to be heard from the court, or otherwise seek judicial relief,” the government said. “In most of the cases, rather than challenge the orders in court, Apple simply deferred complying with them, without seeking appropriate judicial relief.”

Apple disputes this claim. The company told BuzzFeed News that it did indeed send the government a response in the form of an objection, but never heard back. Apple also notes that the government could have moved to compel on these orders as well, but didn’t. Instead, it opted to litigate the San Bernardino case.

While the judge in New York reviews the list of active search requests to inform how to proceed in his case, Apple has until Friday to contest the court order in San Bernardino.

Even as the government has used the list of active searches to highlight Apple’s inconsistency on encryption and law enforcement, privacy advocates may point to it as proof that the government is desperate to break into many other phones — and will use the outcome of the San Bernardino case as a precedent.

In an all-hands memo to Apple employees addressing the legal dispute over encryption, CEO Tim Cook suggested that the national debate over encryption should be settled not by a court but by Congress or a special government panel of experts.

“We feel the best way forward would be for the government to withdraw its demands under the All Writs Act and, as some in Congress have proposed, form a commission or other panel of experts on intelligence, technology and civil liberties to discuss the implications for law enforcement, national security, privacy and personal freedoms,” Cook wrote.