For the past 10 years, I have been spending a chunk of my Sunday afternoons at a sports community centre in north London. Here, for two hours every week, a group of men from around the area go at it on the basketball court, sometimes as if their lives depend on it.

When we play, the atmosphere in this old, rusty gym is almost as electrifying as the neighbourhood itself. We are in Tottenham, in the borough of Haringey, a place as vibrant and multicultural as it is deprived. I lived just up the road, in Edmonton, after I first arrived in London in 2004. With the typical naivety of a newly arrived immigrant, I never saw Tottenham as deprived, just different.

But four years ago, something happened here that served to inform those who didn’t know, or perhaps chose to ignore, the daily struggles faced by a portion of the population. On 4 August 2011, on a road a few minutes’ drive from where we play ball, Mark Duggan, a 29-year-old black man, was shot dead by specialist firearms officers on the suspicion that he was in possession of an illegal firearm. A search of Duggan’s body, motionless in Ferry Lane on that infamous Thursday afternoon, determined that there was no gun on him at the time of his death.

Later that night, accompanied by community leaders and local residents, Duggan’s family marched to Tottenham police station to demand answers. They had called the station beforehand to inform the police of their coming. Still, they were left standing outside for hours, waiting for the commander to come out. The officer who finally agreed to meet them was not deemed to be senior enough to give an official explanation, according to one community leader I spoke to. What followed were violent clashes between local youths and the police, resulting in the destruction of a double-decker bus and many private homes and businesses.

For almost a week, disorder reigned in the capital and other cities around the country. By the time the rage subsided, five people had been reported dead, damage to private and public property ran into the millions of pounds, and thousands had been charged with criminal offences.

Left: The burning Carpetright store on Tottenham High Road on 6 August 2011. Right: Firemen douse the smouldering building. Below: The store in 2015, now a Sports Direct shop.

For the guys I play ball with, though, the riots were not about Mark Duggan. Most of them are first-generation African and Caribbean immigrants born and raised in England in the ’80s and ’90s. For them, much of the unrest experienced in the summer of 2011 was about a community that had reached boiling point.

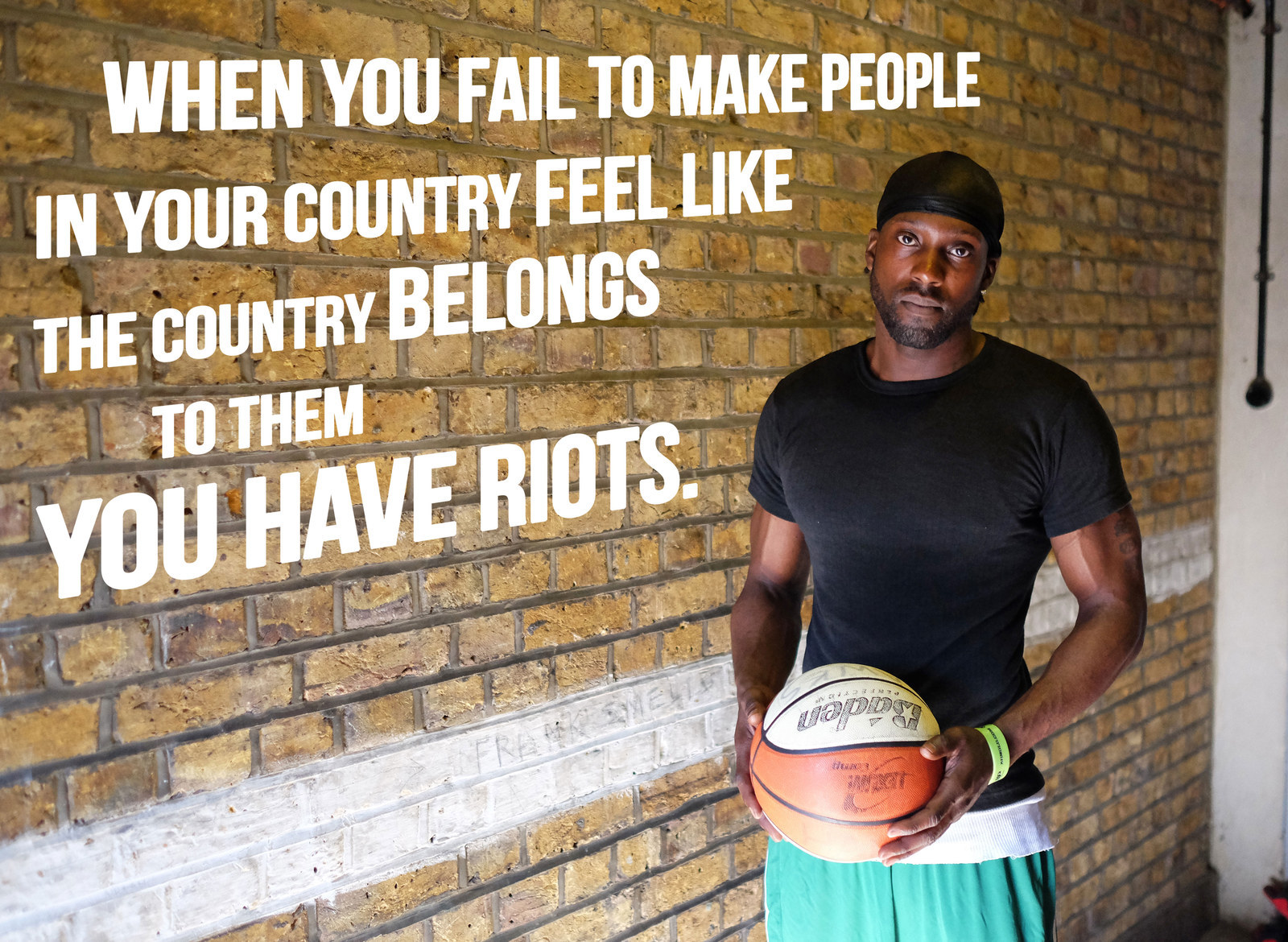

“When you fail to make people in your country feel like the country belongs to them, you have riots,” says Andrew Smith, a 35-year-old Tottenham resident who manages a boxing gym in east London. As the day’s first boxing class begins, Smith, a father of one who describes himself as “British, not English”, tells me: “I don’t feel like I belong here.”

For a long time I didn’t feel like I belonged on that court, either. Basketball is a passionate sport, and emotions run high in our sessions. It’s five-on-five full court, winner stays on. No one wants to lose and wait 20 minutes on the sidelines to get back on the hardwood. When things get really heated, fistfights and ugly shouting matches aren’t unusual. For a 19-year-old kid like me who grew up in Portugal and later in the American midwest, it all sounded and looked a bit surreal.

“We grew up around each other,” Akin Akintola, a 45-year-old youth worker, says at his workplace in Tottenham.

He’s not tall, but Akintola’s toughness and basketball IQ have earned him the respect of all, and he’s not the kind of guy to be toyed with on or off the court. “When things get out of hand on the basketball court we understand each other’s behaviour,” he said. He has been organising the Sunday basketball sessions at the Tottenham Community Sports Centre for almost 20 years now. Any newbie who joins us soon realises this is way more than just a workout.

“It’s therapy 100%,” Akintola says. “That’s the way we release whatever has happened in the week. The only place where we, as black men, can get it all out. I can swear, I can cuss, I can do all that stuff without thinking about the repercussions.”

James, the only white guy who’s been regularly coming to our sessions for years, is a reliable three-point shooter, even if he’s not terribly athletic. He comes in, tries to help his team win by scoring as many three-pointers as possible, pays his money, and goes home. It seems for James, there’s nothing more to basketball than just a way to shed extra pounds.

While talking to the others about racial dynamics in this country one Sunday afternoon after we finish playing, I bring up James and how comfortable he seems around us, but they aren’t buying it.

“I wouldn’t say he’s comfortable with us, he’s just accustomed to us,” one of the men, who chose to remain anonymous, tells me.

Smith is a big character. At 6’4” and around 18 stone, his personality is as dominant off the court as his physical presence is on it. Prior to writing this, I knew nothing of what he or any of these men thought about what happened in their neighbourhood four years ago. Smith knew of Mark Duggan growing up, as did most of those I spoke to.

None of them remembered Duggan as a criminal. For them, he was just a kid from the neighbourhood who did what he had to to survive. It is now widely recognised by both Duggan’s family and local community leaders that while he was not in possession of a firearm at the time of his death, he was on his way to get a gun from someone else. Still, for the locals, it was the manner in which the young father of three was killed – and the Met’s behaviour afterwards – that really stood out.

“Initially I wasn’t sure whether he [Duggan] was black or white, I was just shocked a shooting had happened in north London,” Smith says. “After finding out who he was, his age, a young black man, I wondered what he had done. To me the only thing he could have done [to justify his death] is shot at the police.”

A year before Duggan’s death, a study by the Equality and Human Rights Commission showed that black people in England and Wales were at least six times as likely to be stopped and searched by the police than their white British counterparts – in the West Midlands that number goes up to 28 times as likely. These are the stats men like Smith, born and raised in Wood Green, in north London, have become all too familiar with over the years.

“I don’t actually mind the police stopping me and asking me questions – that’s a normal part of their job,” Smith says. “But I’ve been stopped and searched in a crazy way.”

With his little boy running about the gym, Smith tells me about an encounter with the police outside his house a few years ago:

"I got to the top of my road, drove down the hill, three cars behind, two vans, lights flashing. They jumped out and shouted, ‘Get out of the car, get out of the car.’

"I got out and they said, ‘Put your hands behind your back. I said no. Then they grabbed my arm and put one handcuff on my hand. I said, ‘What are you doing?’ They said, ‘Put your hands behind your back.’ I said, ‘Not until you tell me why you’re doing this, you’re not going to put the other handcuff on me.’ At that point they started kicking my legs, trying to kick me to the floor."

Since 1990, a total of 1,516 people have died while in Metropolitan police custody, according to Inquest, a charity that provides legal advice to the public on contentious deaths in police custody and in the course of their investigations. Of those, 152 were from black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds. In the US, the country to which the UK is most often compared, a black person dies every 28 hours at the hands of law enforcement figures, according to one report. But for those who have had to deal with British police, and still do on an almost daily basis, those statistics are of little consolation.

“The police here are not much better,” Akintola says. “I think if they had guns they would be the same [as in the US].” He was born in Nigeria, and has been living in the UK since his early teens. He openly admits that as a young man, he did things he shouldn’t have.

“Many of us were doing things we shouldn’t be doing, such as signing on [for unemployment benefits] and still working,” he says. “There was no relationship with the authorities.”

But he also spoke about a police force that seemed to be constantly harassing him and his friends for reasons he perceived could not be anything other than the colour of his skin.

“Growing up, one of the first things you do is get a car. All your friends in the car are gonna be black. So when you get stopped [by the police], a bunch of black guys are getting stopped.” He is calm, but his voice holds a tinge of anger. “And a bunch of black guys getting stopped means we’re all gonna get pulled aside, asked questions and searched.”

Accounts of being stopped and searched, of being pulled over by the police and asked questions that no white person in the same situation would be asked, were abundant among the men I spoke to on and off the record. Far more alarming, though, was the general feeling that they all could be the next Mark Duggan.

“It’s intimidating,” Johnny says after we finish playing one Sunday. “It makes you wonder if one day it’s going to be your turn. You second-guess yourself – you’re a free man but sometimes you think, ‘What am I guilty of?’” A 35-year-old electrician from Montserrat who’s been living here since he was 18 years old, Johnny didn’t want to give me his last name.

Of driving a nice car in an area where guys like him are “not supposed to be”, he says: “I don’t think you’re ‘allowed’ to live above a certain level, a certain means. You’re not expected to do as well as your white peers. As soon as you show signs of ability, signs of trying to make it to the top, you’re targeted by the police.”

London is constantly lauded as one of the most multicultural cities in the world, but anyone who comes to our sessions will immediately notice how homogenous the group is. We’re made up of mostly black men, and are all local or previously local residents (I now live in east London).

In March 2013, Victor Olisa was brought in as the police commander for Haringey. Nigerian-born Olisa has a reputation for being an enforcer. In 2003 he was temporarily transferred to work in the Home Office’s Stop and Search programme, where he was part of a small team in the Office for Criminal Justice Reform. According to Olisa’s profile on the Met’s website, “during two and a half years at the Home Office the team’s work was influential in developing models for improving the effectiveness of Stop and Search”.

The Metropolitan police declined my request to speak with Olisa for this piece, but back in a 2013 interview with the Tottenham Journal, here’s what he said regarding his skin colour:

"In some quarters it is advantageous. As a black police officer I will be accepted more easily in some quarters without having to go through all that scene-setting. Some people think, ‘Because you are the same colour as us, you will have experienced some of the same challenges that we have experienced.’ "

But having more black officers in the streets is not necessarily the best way to achieve better relations between police and the black community.

“I believe the type of people who should be joining the police are the people who have been on the fringes of crime,” Akintola said. “Because they have been on the fringes and they understand, they will empathise. You don’t need the kind of people who have been bullied in school and think this is an opportunity to bully someone else.”

Four years after Duggan’s killing, the relationship between the police and Tottenham’s black community remains fragile. Last year, a public inquest concluded by an 8-2 majority that Duggan’s death was lawful. That outcome left both campaigners and local residents incensed.

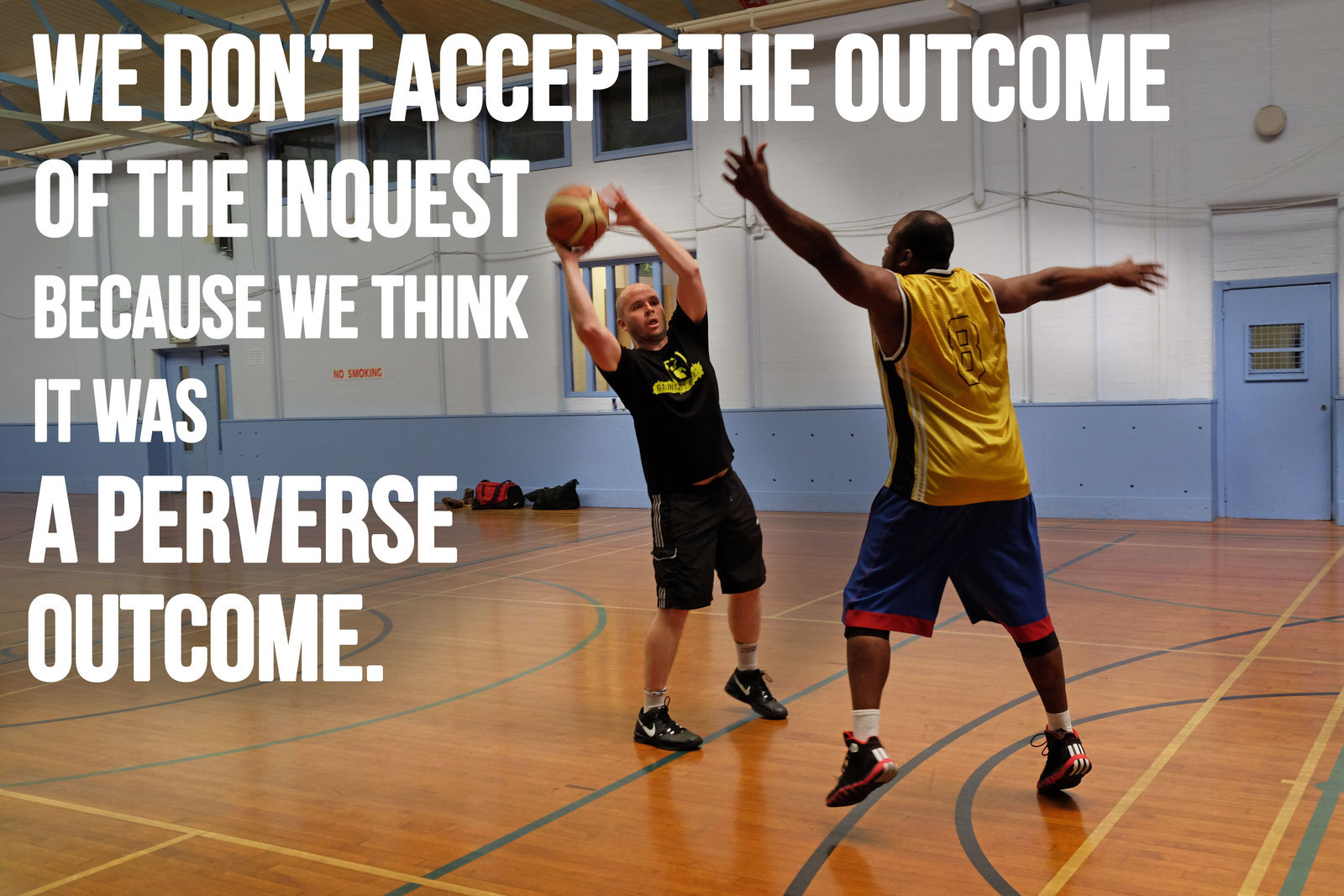

“We don’t accept the outcome of the inquest, because we think it was a perverse outcome,” Stafford Scott, a co-founder of the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign in 1985, tells me at his office in central London. He is now a consultant on racial equality and community engagement. “That they’re now saying someone who was not armed – who isn’t an immediate threat or danger to anybody – can be killed in the streets, and that’s justifiable, can’t be acceptable in a civilised society.”

Scott describes the police force and justice system as not only “rigged” but “protected”:

“What people really have to understand in these situations is that when police are involved in killings, ultimately it is the police investigating the police. I don’t care if they call themselves the Police Complaints Authority or the IPCC [Independent Police Complaints Commission]. They are filled with ex-coppers.”

The IPCC vehemently denied Scott's claim, calling it "irrational" and "without foundation", adding: "Four out of five of our investigators are not former police officers and all our investigators are subject to a rigorous recruitment process and bespoke IPCC training, regardless of their background."

Scott is no stranger to confrontations with the police. In 1985 he was on the frontline of Tottenham’s Broadwater Farm riots, sparked by the death of 49-year-old Cynthia Jarrett – a black woman who suffered heart failure when police entered her home to search for allegedly stolen goods. As in the Duggan case, no police officer was charged with Jarrett’s death.

“Part of the reason why the juries find it so difficult to come to those conclusions is TV programmes like that crap we saw recently, The Met and others, like The Rookies and Motorway Cops,” he says. “All they do is show the police when they are doing police work. They never show the cock-ups, they never show the fuck-ups, they don’t show the corruption.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by the guys I play ball with. Thirty years after the Broadwater Farm and Brixton riots, and 182 years after the abolition of slavery in Britain, there’s still the knowledge, and, sadly, the acceptance, among all the men I speak to, and thousands of black people besides, that this is still a country run by fundamentally racist institutions. And that the machinery of these institutions is set up in such a way as to oppress and sometimes violate the rights of people of colour.

“I’m going on a limb here,” Smith says. “But if Mark Duggan was a white guy, they wouldn’t have shot him down in cold blood just like that, in the middle of the street.

“We are not held to the same rules and standards. We’re just not.”