WASHINGTON — Billy Ray Wheelock doesn't look like someone who walked away from 21 years in federal custody just a few weeks ago thanks to a presidential signature.

But his 1993 life sentence for crack cocaine possession is clearly never far from the mind of Wheelock, who criminal justice advocates hope will humanize efforts to overhaul drug-sentencing laws.

President Obama granted him clemency late last year, as part of a larger administration effort to reduce the number of people serving long sentences for nonviolent drug convictions. Wheelock has lived as a free man since leaving a halfway house in April, but has his time in prison close at mind.

"You can't give your word to everyone, you know? But I gave it to about 10 guys," Wheelock said, describing the prison culture that can closely tie inmate to inmate for protection. "My wife told me when I got out that I need to let them go, to put it all behind me, but I can't do that. Whatever they need, I'll be there for them."

On Tuesday, that meant walking the halls of Congress and asking politicians to take time in an election year for changes to sentencing laws. It's an uphill climb, he acknowledged, but Wheelock — like the advocates on both sides of the aisle — said things are changing. Wheelock argued the main source of that change was the election of Obama in 2008.

"It's politics. You're now being elected by the minority. We get to talk to you, we get to elect you," he said. "We [inmates] can't vote, but we can talk to moms, grandmothers, aunties."

Wheelock believes "a lot" of the people who voted for the first time in 2008 did it at the urging of relatives in prison, desperate to see someone who wanted to change those laws in the White House.

"How many people know someone or are related to someone in prison?" he said. "When you ask that question to black people or Hispanic people? Shoot. It adds up. It's real."

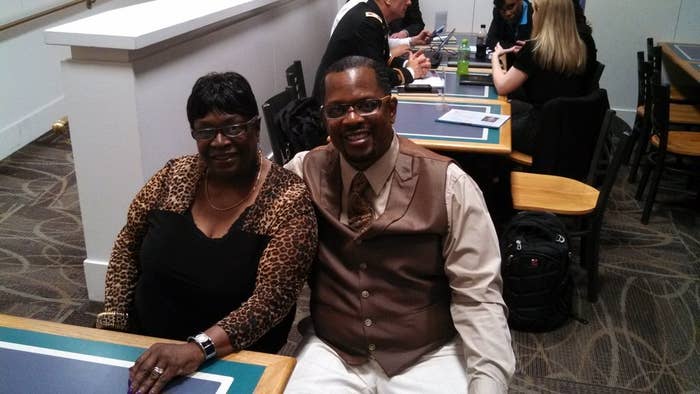

The 51-year-old Wheelock was 29 when he was sentenced to life in prison. Over two decades in prison, he learned how to work the system and become a self-described "legend" behind bars. In an interview in the Longworth House office building cafeteria ahead of a day of lobbying sponsored by the ACLU and Families Against Mandatory Minimums, Wheelock said a dangerous concoction of racial politics and political expediency led to sentences like his, at a time when crack conviction sometimes carried with it 100 times the penalty for powder cocaine.

"I don't want to play the race card, but it is what it is. When they see a black youngster or a black man becoming very wealthy by selling that stuff, it became a big problem to them," he said. "You see an 18-year-old in the projects with a Benz. It doesn't match. So they did a big vendetta: 'We'll pass this law, lock them all up, give them harsh sentences and then get rid of them, get rid of the problem.' But the thing they forgot is, we have people that love us. You can't just throw us away. We have people who are going to fight for us."

Wheelock said the race-based opposition to reforming sentences is melting away somewhat, given changing U.S. demographics and a minority president. But throwing the book at a drug offender is still the politically safe route, he believes. And that's the challenge.

"Congress is set in their ways and they've been there for too long to understand the change," he said. Wealthier and whiter than the general population, Wheelock said members of congress are sealed off from a lot of social problems.

"When you become invincible, you live in a bubble, you only understand what's going on outside that bubble," he said. "How can you solve a problem if you don't understand it?"

But that may be changing too. In 2010, the Democratically controlled Congress passed with bipartisan support the Fair Sentencing Act, a law that dramatically reduced the extra time given to crack offenders, changing what statistics showed were laws that disproportionately affected black and Latino men. When Republicans took control of the House the next year, and Tea Party icons like Sens. Rand Paul of Kentucky and Mike Lee of Utah took their seats in the Senate, bipartisan efforts continued but got stuck, advocates and Hill aides say, on opposition from some Republicans wary of abandoning their "tough on crime" image. Wheelock was in Congress on Tuesday to help lobby for the Smarter Sentencing Act, championed in the Senate by the unlikely coalition of Lee and Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill. Essentially, the act would grant federal judges discretion to ignore some mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders and give existing inmates convicted before the 2010 law took effect the right to ask for a review and possible reduction of their sentences.

A lot of Republicans like this idea, but not enough key figures to help move the bill in the GOP-controlled House. Even pro-reform conservatives have been wary of embracing Obama's plan to grant clemency to thousands of offenders in Wheelock's position, and law-and-order Republicans have condemned the plan as an illegal use of presidential power.

Wheelock has more in common with the tough-on-crime types than they might expect. A Colorado resident, Wheelock said he opposed his state's recent efforts to legalize marijuana.

"I don't agree with that. Because of the kids. As adults, OK yeah, but it's going to get in the hands of kids. It's going to touch them. It just is," he said. "It's not a drug that really drives you too, too crazy but we forget where we come from. We forget that there's a God, we forget a lot of things. And when you try to fight that you know what you're going to get with that one."

"The law has lost its religion. The justice system has lost its religion," he added. "And if you lose that way, just throw it up in the air and let it fall where it may. But it doesn't make it right."

Were he on a jury today and asked to judge a man who committed the same crimes he did — "conspiracy to distribute more than 50 grams of crack cocaine; possession with intent to distribute more than 5 grams of crack cocaine within 1,000 feet of a school; possession with intent to distribute crack cocaine" — Wheelock said without hesitation that he'd convict. And he'd expect that man to go to prison for his crimes.

"Of course I'm going to put him in jail, but he's not going to have to do a life sentence. He's not going to have to do 21 years," he said. "But he's going to get spanked. Jail time for any crime, especially one that's committed repeatedly, yes. Justice must be served. If you don't, you're going to have the Wild, Wild West."

What Wheelock wants is not a wholesale change to the drug laws. He wants fairness, he said, and he wants the men he left behind in prison given the same chance to review their sentences he got thanks to the president.

Even as he made his case for reform, laying out a detailed defense of changing sentencing rules and describing a life with his wife, Berna, far removed from prison, he still carries the weight of a life sentence.

"Oh, I'm mad as hell," he said. "Don't get me wrong. But it's bigger than me."

Wheelock carried with him Tuesday an email he wrote on Dec. 19, 2013, the day after he got word of his clemency. "I can't stop hearing the screams of those who are No Longer on this earth, and of those who are still fighting for their Right to be Free," he wrote. "I wish I could share these Screams with the President, with Congress and with the World."

Sitting in the congressional cafeteria, preparing to meet a member of Congress for the first time in his life, Wheelock said the situation was reason enough to give hope to anyone imprisoned like he was.

"Keep in mind I was still a prisoner when I wrote that," he said. "Who could have thought it would actually happen?"