The skeletal remains of a four-inch lobster have lingered somewhere in my parents' home for nearly 20 years.

It started with the 1993 FAO Schwarz holiday catalog. I was 10, and I flipped through it at the kitchen table of our railroad-style apartment, emotionless, like a creepy zombie child. As a kid in the '80s and '90s, few things were quite so thrilling as the moment you opened the mailbox to find this catalog, filled with life-size stuffed snow leopards and Mercedes-Benz kids cars with prices too high to list. Well aware of my parents' inability to afford most of the items in the catalog, I glossed over most of the toys — until! I laid eyes on the holy grail of Christmas presents: a live lobster kit.

Becoming the eager guardian to a gaggle of nontraditional pets was in the cards for me from an early age. As a child I lived near a live poultry market in Brooklyn, which my mom and I walked to often. Four-year-old me assumed any homogeneous collection of live animals in a small, dimly lit space was a zoo, and my delighted mom confirmed it. Maybe she didn't want to explain the slaughter process to me, but more likely, she simply realized that, for a lower-middle-class family, producing a child who believed a group of chickens in small wire cages constituted a zoo was like hitting the parenting jackpot: free entertainment only a 10-minute walk away.

In those visits — traipsing through the narrow, sawdust-sprinkled aisles, greeting and waving at dozens of doomed fowl — my pseudo-hippie mother instilled in me a sense that all living creatures deserved compassion. This included the stray cats for which she and my dad built winter shelters in our backyard, and it included a holiday collection of mail-order micro-lobsters.

Never in my wildest dreams did I think I'd ever find something so wondrous and so affordable in that catalog: For just $50, nine blue Australian lobsters would arrive along with a lobster "condo." And man, they could not arrive soon enough. Sea life was fascinating to me; I would even apply to a marine biology–specialized high school three years later. I circled the item number in a red Sharpie and handed it to my parents with a convincing plea. "This looks interesting," my mom said. I figured it was in the bag.

And so Christmas Eve arrived, along with my nine new crustacean friends — no more than three-quarters of an inch long, and almost completely transparent — each in its own little plastic baggie filled with water. How anyone could legally get away with marketing these water-cockroaches as "blue" Australian lobsters was an afterthought; I was already excitedly assigning them names, watching them balance on their teeny little tails and lift their micro-claws into the air to catch brine pellets, to care too much about the fine print. We set up their living quarters, a four-tier tank with a base and nine cubicles, each roughly 2 square inches, and I spent hours watching these sea aliens investigate their surroundings and disassemble their food with tiny little pincers.

The initial euphoria subsided quickly, and my holiday dreams swiftly turned into nightmares. A few of the smallest ones died or got stuck in the tank's filter over the next few weeks — the "condo" was clearly not devised to accommodate the most curious baby lobster, Tiny Tim, whom I had to extricate more than once.

Even more horrifying was the "molting" process, in which the lobster would literally pop out of its shell every week or so and, like some auto-cannibalistic demon, eat the entire, hollow replica of itself immediately. I'd wake up in the morning to find a ghost shell swaying alongside its lobster twin, as though Madame Tussaud herself had paid a visit but left before finishing off the eyes. Every so often the animal would mount its former self, mini-claws pulling it apart — sometimes yanking off a limb, sometimes brutally attacking its old face. No one had prepared my innocent 10-year-old eyeballs for this barbarity.

After a few months of traumatizing lobster-rescue experiences no child should ever be exposed to, springtime rolled around, and just four lobsters remained. I was OK with this. I could not "play" with the minuscule beasts — my attempts at forging any sort of emotional bond with these creatures were rebuked with each vicious pinch of my flesh. Still, after half their cohort died off, I could at least remove the cubicle dividers and give each lil' guy (or girl?) their own tier in the tank — to be free and live the roomy lobster life they each deserved.

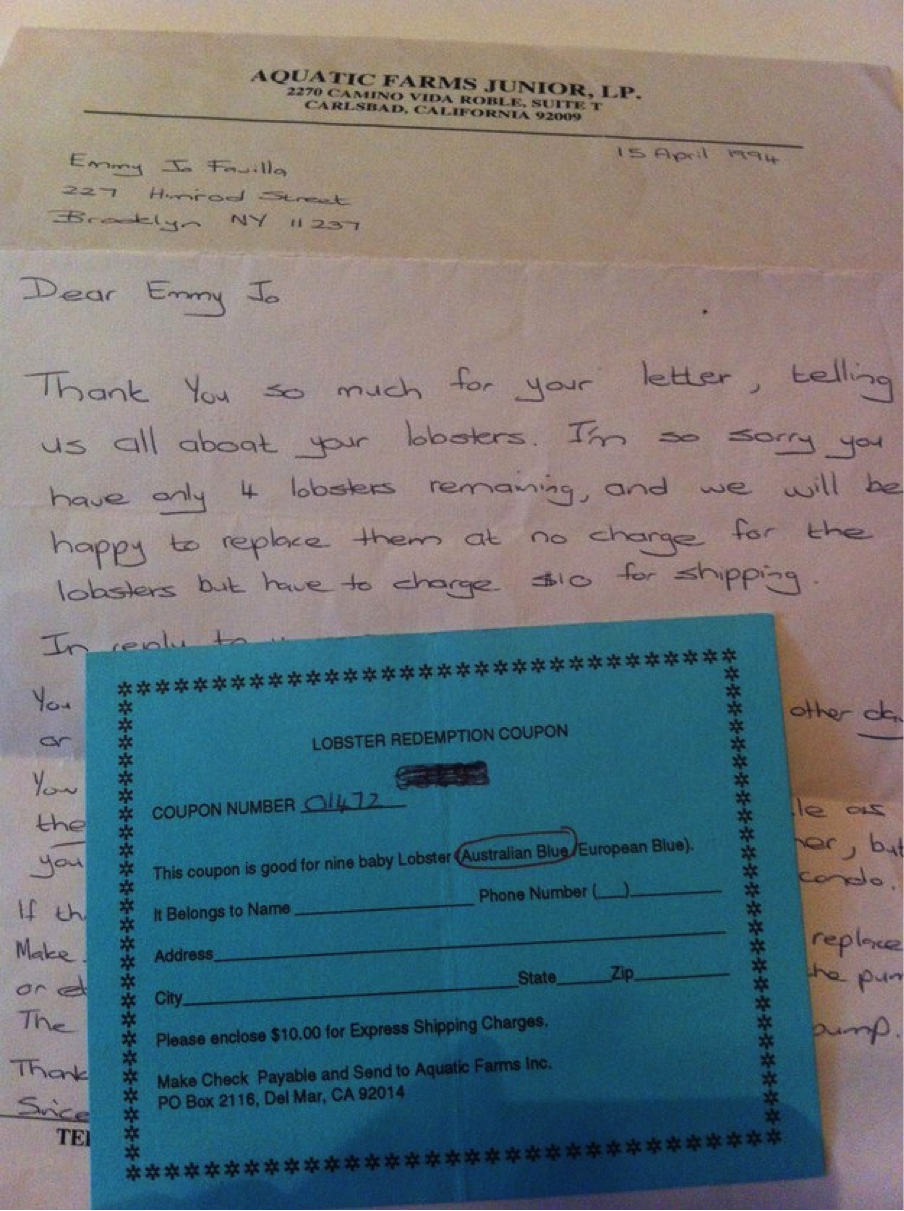

It was around this time that I sent the company from which they were delivered a letter with several nervous questions. Based on the letter pictured, Aquatic Farms Junior hires bubbly middle-school students to respond to customers:

My parents and I declined the company's offer for nine additional baby lobsters, and soon we were left with only three. They outgrew their "condo," so we bought them a fancy big tank that we set up across from the refrigerator. It was about 3 feet long, with two dividers, bright blue gravel, and fun decorative bridges for each one to hide under. The lobsters were unmoved.

One of the survivors, Big Joe, lived through five more years and one potential suicide attempt: diving out of his tank, somehow surviving the three-foot drop to the floor, dragging his ungrateful crustacean body through two rooms, and crawling into a shoe in my dad's closet. Upon discovering his dried-up body, seemingly lifeless in an unsuspecting loafer, we popped him back into the water (just in case), and he was as good as new within the hour. Another poor soul was inspired by Big Joe's daring feat, and — despite a weeklong, family-wide investigation — we never found him.

When I was 13, we finally ran out of lobster food and had to order more from Aquatic Farms Junior. A big box arrived, and I opened it — only to discover not just the brine pellets we had ordered, but nine more baby lobsters that we had most definitely not ordered. My mom and I were panic-stricken. It was a late Saturday afternoon and the local pet store had already closed. We knew we had to put them in fresh water immediately, so we found the biggest bowl in the kitchen cabinet and threw them all in with some food, hoping for the best. What's the worst that could happen, we thought.

Though I would not formally learn about Darwin's theory until a year later, in freshman biology, I was about to get a head start: Within 24 hours, these infant lobsters had all eaten one another, leaving the strongest one (a monster) standing. It happened in slow motion — every couple of hours, we'd notice there were fewer lobsters remaining. They ate all but each other's eyes.

Just before bed, my mom and I stood at the kitchen table, staring in silence at this lone baby lobster, surrounded by eight pairs of microscopic eyeballs, swimming nonchalantly in an olive green Tupperware bowl filled with tap water. I had never witnessed anything so obscene take place under my own roof. My mom, too deeply shocked herself, had little to offer me in "well, that's nature"-type comforting explanation. So I crawled under the covers and spent the night half-asleep, haunted by visions of the Great Lobster Massacre of 1996.

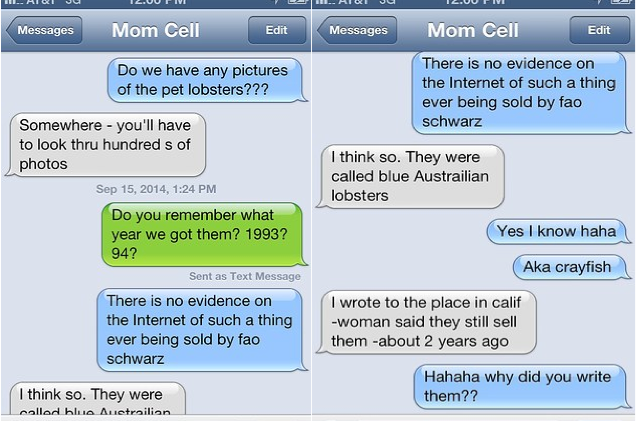

In recent months, I've recounted this story many times, to many different people. There is absolutely no internet evidence — at least none that I can find — suggesting such a product was ever sold in the early or mid-'90s by FAO Schwarz. Or ever, at all, by anyone. Sometimes I am led to believe I dreamed up the whole thing. I texted my mom asking if we had any pictures of the lobsters, and a startling conversation ensued:

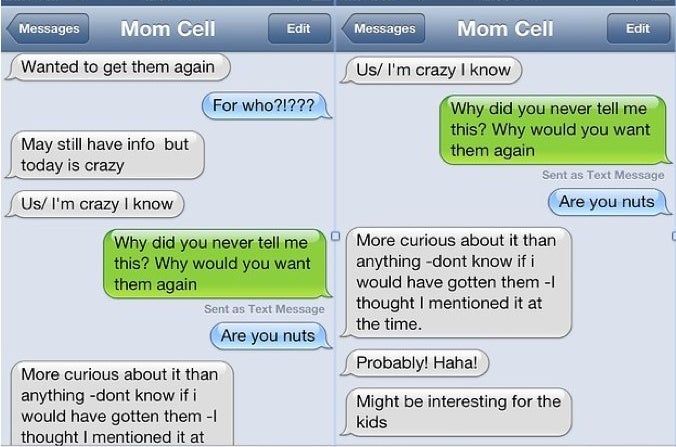

In case you missed the kicker here: Just two years ago, my mom CONTACTED THE LOBSTER DISTRIBUTOR to (maybe) get MORE pet lobsters. But why? "The kids" she mentions are the children who attend the day care she runs — which is distressing, given that the lobster-related traumas I endured from 1993–1998 are something I would never wish upon another wide-eyed, innocent small human.

But it's refreshing, I suppose, that even in the era of YouTube, my mom retains the same curiosity and enthusiasm she did 20 years ago. She's always believed that the world should be explored actively, not passively — even if that means learning about the natural instincts of crustaceans via the compromised safety of one's own appendages rather than a computer screen or toy. So, I guess, thanks, Mom? For always encouraging me to find the entertainment and excitement in every situation — and to create my own if I couldn't readily find it anywhere.

And, of course, for the fear that one day, a little lobster ghost will come flying out from underneath the refrigerator to find me, wanting to know why he didn't get a proper burial.