It is the middle of the night, and there is something very wrong in my apartment. I leap up from my bed and rush to the closet and crouch down and throw aside my shoes, which are arranged on a rack on the floor. I know I must work quickly; I am breathing fast and hard. There — there, behind the shoes, I see it: I don’t know what it is, but it needs to come out, or I am going to die. I pull and pull and finally get it out.

But something is still wrong. I am now completely panicked, and I jump back onto my bed and lean over the half-wall that my bed is up against, overlooking the hallway. There, I see what’s causing all the problems, and I push it downward and off the wall with all my might. It shatters loudly, glass flying everywhere.

Then, finally, I wake up. My two dogs are cowering in the corner, and I put on shoes to sweep up the glass. I am confused and embarrassed, though there is no one besides the dogs there to see that I just pushed a framed poster off a wall and broke it. I clean up the glass and go back to sleep, and it is not until the morning, when I see my shoes scattered everywhere, that I look into the closet and realize that I have also ripped the TV cable completely out of the back wall of my closet.

These brief but incredibly vivid nightmares happen for years: they're never quite so violent as that first one, which happened around 2003, but almost always as scary. I don't know what to call them, but they become a familiar part of bedtime, and there are times when I am afraid to go to bed because I know that just as I start to fall asleep, I will be jolted aware in a state of sheer terror. Then, just as suddenly as they start, they ebb for a time, and I wonder if I've gotten better. But they always come back.

Here are some other things I've believed in the middle of the night:

They are monitoring my breathing. If I don’t hold my breath and stay completely still, I am going to die. I am not allowed to move at all, or they will know, and they will kill me.

I need $5,000. I need $5,000 so desperately that if I don’t get it, I'm going to die, and I wake up screaming that I need money.

There is someone trying to get in the front door of my apartment, so I jump out of bed and run to the door and unlock it.

A woman has come to my apartment and taken all of my things — everything that I own — and now she has laid down in bed next to me and she's wearing a plaid shirt, one of my plaid shirts, and I scream.

I see a huge roach, or a rat, in the bed, and I scream. My boyfriend wakes up and I say I have seen a creature, and he is half-asleep himself but he grabs something to kill it but there is nothing there.

The walls and ceiling and floor are all slowly closing in on me, compressing, so that I will suffocate if I don't escape. In another version, the ceiling is about to cave in on top of me and I will be crushed to death.

I need to escape, but I'll have to be quick, and I will need to have the necessary provisions with me. I run to my closet and grab a T-shirt and shorts and a bra and underwear and a pair of flip-flops, and I put them on a chair in the living room, everything neatly folded, so that when it comes time to flee I will be prepared.

I let a girl into the apartment and she steals all of my stuff, and I jump out of bed and run into the living room to try and stop her.

I am at my parents’ apartment, sleeping in the guest room, and I need to escape, quickly, or else I am probably going to die, and so I climb up on the desk by the window so that I can open the window and jump out of it, and it is not until I am on top of the desk and about to open the window that I actually wake up.

I sit up, bolt upright, in bed, and it feels like my heart is in my throat, and I need to get out of the bed as quickly as possible, or they will kill me, and so I leap over my boyfriend, who is sleeping next to me, and land with a thud on the floor, and he wakes up and asks what the fuck I am doing. When, a few months later, we go looking for a new apartment, we rule out anything with a loft.

In June 2010, a few weeks after the 35-year-old artist Tobias Wong hanged himself in the middle of the night in his East Village apartment, the New York Times writes that Wong was "no tortured artist, locked in a downward spiral. ... Complex, mercurial, mischievous — he was all those things but he was not miserable." But the article also points out that Wong had for years suffered from so-called "parasomnias," a catch-all category of sleep disorders that can include everything from restless leg syndrome to so-called "sleep sex." His boyfriend, Tim Dubitsky, tells the Times that Wong "had no history of mental illness" and "wasn't even seeing a therapist" at the time of his death — but he notes that the parasomnias did seem to get worse when Wong was under stress.

One part of the article sounds especially familiar: "Then there were the troubling occasions when [Wong] showed a capacity for violence. Barbara Moore, an art historian and friend, said that Mr. Wong told her earlier this year that he had pulled a treasured Joseph Beuys artwork off the wall while sleeping and threw it across the room, shattering the glass." This is described as one of Wong's "night terrors," which the Times says is "a half-waking nightmare that the subject is unable to snap out of." I've never heard the term.

I type "night terrors" into Google and learn that they are most common in children, who tend to grow out of them, and that it's estimated that only around three percent of the adult population has them — and that they usually happen to people who had them as children. They generally start with some sort of abrupt arousal out of sleep, often involving a scream, at which point respiration and heart rate both increase and the subject feels panicked. What differentiates night terrors from plain old nightmares is that night terrors occur during so-called slow-wave sleep, before REM sleep begins, whereas nightmares are actual dreams that occur during REM sleep. Night terrors are not dreams; they are best described as a half-waking, half-conscious state.

I learn that when the new version of American Psychiatric Association's massive mental health reference book, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual — to be known as DSM-5 — is released in May 2013, sleep terrors, which will fall under the "arousal disorder" category of sleep disorders, will be defined thusly: "Recurrent episodes of abrupt awakening from sleep, usually occurring during the first third of the major sleep episode and beginning with a panicky scream. There is intense fear and signs of autonomic arousal, such as mydriasis [pupil dilation], tachycardia [accelerated heart rate], rapid breathing, and sweating, during each episode."

That seems accurate. But now that I have this information, what am I supposed to do about it? For it is that same summer of 2010 when my terrors suddenly get much worse. I am definitely under stress: My boyfriend of three and a half years and I break up, and after I move out of the apartment we shared, I start having episodes almost every night. My research tells me that most people who suffer from night terrors describe episodes that sound familiar: They feel suffocated, they are about to die, there is someone in the room with them. That doesn't, of course, make my individual night terrors any less scary, and it crosses my mind that I could actually scare myself to death.

The prevailing theory about Tobias Wong's death was that he hanged himself while experiencing a night terror. I imagine that something in his mind told him that hanging himself was the only way to escape whoever, or whatever, was chasing him, in the same way that I have thought that the only way to save myself was to jump out of a window or smash a pane of glass.

I realize that I want to talk to Dubitsky, both to find out what it was like for him and also to see how closely my experiences dovetail with his. If unintended suicide is the logical extreme of a sleep disorder, am I in imminent danger?

When I eventually meet Dubitsky in person, he's visiting New York from his home in Hawaii, where he moved to do a reforestation project on a friend's family's farm — and for now, he's planning on staying there. He's tall and thin and boyishly handsome, with light brown hair and a striped shirt.

We order drinks and talk a little bit about my own experiences — I tell him that it was the Times article about Wong, whom he calls Tobi, that made me realize what might be going on with me. Dubitsky, who is now 34, tells me about the first time he experienced Wong's sleep issues — in 2005, when he awoke to find Wong chopping up vegetables to feed a dead cricket he'd fished out of the trash. For a time, Dubitsky says, Wong's behavior was odd, but not particularly alarming. After all, he'd been a sleepwalker and sleep eater as a kid — to prevent him from wandering into the kitchen and rooting around in the fridge, his mom would leave a plate of food next to his bed. But then it started getting violent.

"It usually flared up in times of stress, when he was busier with work. It wasn't uncommon for him to work days on end," says Dubitsky. Wong's studio was in their apartment, and Dubitsky says he would often go to sleep by midnight while Wong was still working. "Sometimes I feel now that the only kind of sleep he was getting was kind of sliding into an automatic sleepwalk. He wasn't ever really lying down." And so his habits created a vicious cycle. "If he had an episode, that would make him more exhausted. That would make him more stressed out."

Perhaps the most disorienting aspect of having parasomnias is the feeling of being out of control, of having a part of your brain that's focused solely on very primal instincts — mostly fear and danger — take over. And it raises the question of how well we can ever actually know ourselves, let alone another person. For the partner of someone with a parasomnia, that's got to be the scariest feeling of all.

"I didn't know how to react. I didn't know what to think," says Dubitsky. "The idea that someone I've been with for years and years and years — I'd never seen him behaving like this. He would be screaming. There was one time I woke up because we were in bed and he was yelling at me. The things he was talking about didn't make sense. I was like, 'Honey, you're sleepwalking.' I'd try to go over and just try to calm him down but trying to calm him down would just set him off. Sometimes I'd just try to leave him alone, or go in another room. But whatever story he was playing out in his mind, the only way to figure it out was to be in contact with me. Wherever I would go in the house, he would just follow. He was very tenacious."

No one really knows what happens in a sleepwalker's brain while they're sleepwalking, because it's really hard to capture images of a sleepwalker's brain. As the sleep researcher Rosalind Cartwright explains in her 2010 book The 24-Hour Mind: The Role Of Sleep And Dreaming In Our Emotional Lives, when researchers managed to image a 16-year-old sleepwalker’s brain activity, they found that the boy was "emotionally aroused and his body active, while at the same time the higher mental processes of judgment, rational thought, self-reflection, and memory were still asleep." She concludes that sleepwalkers "seem to be caught in a mixed, in-between state; both brain scan and behavior suggest they are partly awake and partly asleep." In this state, both the brain's frontal and pre-frontal lobes are not working; the sleepwalker is focused solely on those extremely basic motivations.

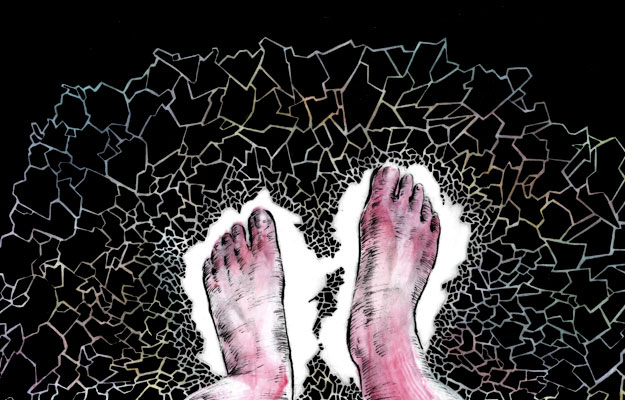

This description jibes almost exactly with how Dubitsky says Wong behaved — just more violently. "The first time I was really scared, he had been yelling at me while I was sleeping," says Dubitsky. "He was saying things that had loose relevance to real life, or to our life together. Maybe it was something in his mind that he had laid out, I don't know. But as far as anything real world, time and space, it never happened." Wong screamed at Dubitsky to get out of the apartment. "He's picking up anything and everything to throw at me. I was on the couch. And then shit just started flying. Dishes, vases, furniture. We had a cinderblock that was a piece of his art. I had a two-liter glass bottle of something; he threw it at me. I ducked, it hit the window at the front of the house. It's getting really violent. We had two 4'x8' mirror things running across this filing cabinet that was set up to be a wall piece, furniture. He just crashed them down. He was barefoot. The floor was covered in glass. He was walking across it like sand. His feet were gushing blood. And he doesn't notice. He was just going at it. At one point I just said if you continue to do this I'm calling the police. And that didn't even register. The way he reacted, it's like he didn't know what the police were. It really meant nothing to him. It didn't even register with him. I'm calling, I'm on the phone, shit's flying everywhere."

But when the police arrived, they seemed dubious. "I said, 'I don't know what's going on, but I need help. Something's happening,'" says Dubitsky. "But they're not prepared for that sort of thing. They weren't even ready to hear sleepwalking. They thought, domestic abuse." The police asked Dubitsky what he wanted them to do. "I said, 'I don't know, what can you do?' I don't know what they can do — I don't know what I expected them to do. Just — help."

The couple were similarly stymied, Dubitsky says, when they tried to get help from the medical community. "We started looking for a treatment, for therapy or something. There's nothing," he says, his voice rising. "No one wants to touch it. They were like, it's not a lucrative business, you're never going to find someone to treat this. They wanted to throw pills at him. But sleeping pills would automatically put him into it."

The weeks leading up to Wong's suicide, says Dubitsky, were particularly stressful: Design Week and ICFF, the International Contemporary Furniture Fair, were coming up, and he was also working with a project that was in a time zone almost exactly 12 hours ahead. "So he was working full time here and then at midnight or so he was getting ready to get on a video conference call to China or something," says Dubitsky. "So he's working around the clock. In between he'd do a little sleepwalking to McDonald's. He loved Balthazar, and one time he was aware in his waking life that a friend was having a meeting at Balthazar and he showed up to that."

I ask whether he thinks of Wong's death as a suicide.

"I don't know what else to call it, but no," he says. "I saw him before I went to sleep and he had that look like he was staring through my head; he wasn't seeing me at all. So I knew he was in that state. But I don't know what else to call it. Accidental suicide?" (The sleep researcher Mark Mahowald calls it "parasomnia pseudo-suicide.")

Wong's death was ruled a suicide by the New York coroner's office, and some suspect that Wong must have been more troubled than Dubitsky knew, and in fact intended to kill himself that night. But I can't help but think of just how terrified I have been when I'm half-asleep, and it seems not only possible, but probable, that Dubitsky is right.

I leave the restaurant feeling shaken. I have a milder form of Wong's condition, but how can I ever be sure that I won't get worse? There's real anger behind Dubitsky's words, the feeling that no one — not Dubitsky, not the medical community, not the police, not Wong's parents, not Wong himself — was ever able to help him.

Until I started trying to figure out what was wrong with me — and why — I had a near-unquestioning, possibly naive faith in the power of modern medicine, and I'm lucky in that I've never had a disease or an illness that doctors have been unable to cure. So naturally, when I want to know what's going on when I sleep, I decide to visit a sleep doctor. Surely, by examining my brain, he or she will be able to give me not just a diagnosis, but a cure.

When I walk into the office of the New York Sleep Institute, which is beneath a Duane Reade in a dorm-like brick building in Manhattan's Murray Hill neighborhood, the first thing I notice is that it is in fact also devoted to the study of epilepsy and other neurological diseases. They also have copies of a glossy magazine/brochure, produced by the makers of Ambien, called Pillow Talk, whose cover lines include "SLEEP: The Ultimate Beauty Secret?"

During my initial consultation with the doctor, I tell her my sleep history, and she agrees that it sounds like I could have night terrors. She suggests that I come back to the Institute for a sleep study, an overnight visit during which I would be hooked up to an EEG, my every breath and toss and turn monitored by a technician, the whole night recorded on video. But then she says: "You probably won't have any parasomnias while you're here, but we can still get a sense of how you sleep." I wonder, then, what exactly they can glean, but tell myself that at least I will get some information about my sleep patterns, which seems better than none at all.

A few days later, I'm changing into my pajamas in the bathroom connected to the eerie, windowless bedroom inside the Institute, and regretting that I forgot toothpaste. I have, however, remembered to bring face wash and moisturizer, in addition to a magazine, a book, a notepad, and a DVD of the movie Metropolitan. The nurse tells me to change into my "sleeping clothes" and wait for her to come back so she can hook me up to the EEG. First she threads wires underneath my shirt and down through my leggings, so that they can monitor whether I have restless leg syndrome. Then she starts applying a viscous gel, the kind used when you get a sonogram, on various parts of my body — legs, arms, scalp, face — and attaching electrodes to my skin. She sticks a breathing apparatus up my nose so they can tell if I snore, and also attaches a monitor to my finger so they can monitor my pulse. She puts a stocking cap over my head so that I can't rip off any of the electrodes in my sleep, and tells me that I can roll over, but if I have to go to the bathroom I’ll have to call her so she can disconnect me from the box that all the wires feed into, which I am sleeping next to. I feel like Frankenstein's monster, and I am worried that I won't be able to fall asleep — but other than at one point having to ask the nurses who are in the next room to keep it down, I fall asleep relatively quickly and am in fact still slumbering when the same nurse wakes me up at 6 a.m. There is goop stuck in my hair and all over my skin, and I almost fall asleep again in the cab on the way home.

When I go back to the doctor to get the results of the study, there are few revelations: "You had no non-REM parasomnias and no evidence of REM behavior disorder," she tells me. "You had an hour of REM sleep total. Your sleep architecture" — the structure and pattern of my sleep — "was totally normal." I do, she says, have a slight case of a disorder that is on the same spectrum as sleep apnea, but not enough for her to be concerned, she says. I also, she tells me, had "very mild snoring."

"So," I said. "How do I get cured?"

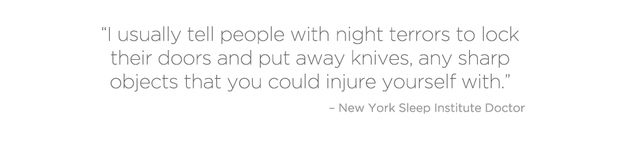

"A stage three parasomnia is very unusual to not have as a child and get as an adult," she says, referring to night terrors. "But really, it’s a benign thing. You’re not at risk for other disorders. I usually tell people with night terrors to lock their doors and put away knives, any sharp objects that you could injure yourself with."

This seemed not overly reassuring, and I think about Tobias Wong as she gives me a prescription for an extremely low dose of the anti-anxiety drug Klonopin, which she says would help keep me in stage two sleep and therefore presumably help me avoid the night terrors.

I take the Klonopin for a few weeks. The terrors don't stop.

What happens when we sleep has been the subject of fascination for centuries — in part because it has always been, and continues to be, mysterious. We don't really know what happens to us when we sleep; we only remember — in patches, and probably inaccurately — what we dream — and as Plutarch wrote, sleep is deeply, unknowingly personal: "All men whilst they are awake are in one common world: but each of them, when he is asleep, is in a world of his own." More ominously, Hamlet famously proclaims that sleep is the closest thing in life that we have to death (though modern sleep scientists would quibble with this description):

"To die, to sleep—

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to — 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished: to die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream. Ay, there's the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause."

People in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt developed sleep "aids" that included blood-letting and medicinal plants, while also being responsible for the first known attempts at dream analysis, beginning as early as the 3rd millenium B.C. Later, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh goes to his mother, a goddess, to interpret two dreams he has after the elders of the town of Uruk turn against him. Around 350 B.C., Aristotle became interested in sleep, eventually concluding that people awake from sleep when digestion is complete. The Jewish philosopher Maimonides, in his 12th century Hilchot De'ot (Laws of Personal Development), laid out sleep guidelines:

The day and night [together] are twenty-four hours long. It is sufficient to sleep for a third of this, i.e. eight hours, which should be at the end of the night, so that there will be eight hours from when one goes to sleep to sunrise. One should get up before sunrise.

and

One should not sleep on one's front or on one's back, but on one's side; at the beginning of the night one should sleep on one's left side, and at the end of the night on one's right side. One should not sleep close to having eaten, but one should first wait three or four hours. One should not sleep during the day.

And sleep is a recurring theme in Shakespeare — Lady Macbeth sleepwalks; in Othello, Iago lies to Othello by telling him that Cassio was talking in his sleep about Desdemona.

The first scientific experiments with sleep began in the 18th century, when French physicist Jean Jacques d'Ortuous de Marian performed an experiment with plants and a darkened room, and came up with the theory that humans exist on so-called Circadian rhythms — meaning that our bodies are governed by a 24-hour cycle, a biological clock that persists even in complete darkness.

But while sleep has fascinated human beings across cultures for thousands of years, that fascination has not always contributed to understanding, and the modern era of sleep research has proceeded relatively slowly. Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung helped usher in the modern era of dream analysis; in different ways, they both suggested that dreams are ways in which we deal with things we can't confront in our waking lives. In the late 1920s, a Swiss psychiatrist named Hans Berger discovered so-called "brain waves," and researchers realized that sleep could be measured scientifically by looking at activity in the brain through the use of electrodes. Berger found that he could measure patients' brain movements when they slept, paving the way for the identification, in 1952, of rapid eye movement (REM) by a researcher at the University of Chicago named Eugene Aserinsky, who then discovered that most dreaming takes place during REM sleep. The first sleep labs were concerned less with learning about sleep disorders and more with simply figuring out typical sleep patterns. And the professionalization of sleep medicine itself is relatively new. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the field's main professional organization, wasn't established until 1975, and indeed, much of what we know now about how we sleep and what happens while we sleep has been discovered only in the last 20 to 30 years.

That's partly because much of sleep research has been fueled by the pharmaceutical industry, which focuses largely on people who have trouble falling asleep. Not surprising: A 2002 National Sleep Foundation poll found that 58 percent of Americans have insomnia at least a few nights a week, and in a 2009 National Sleep Foundation study, 27 percent of respondents said that they'd had disturbed sleep as recently as the last few weeks because of financial worries. But people have suffered from insomnia — usually temporarily — for ages. The first sleeping aids were barbiturates like Seconal and Nembutal, which doctors prescribed as sleeping aids beginning in the early 20th century and continuing through the 1970s, when the benzos — Librium, Valium and Dalmane — came into favor. But today, probably the most well-known and increasingly controversial sleeping pill is Ambien, which is part of a class of hypnotic medicines called imidazopyridines that help people fall asleep, though they aren't intended to help keep people asleep — a subtle yet important distinction. First released in Europe in 1987, it was approved for use in the U.S. in 1992; in 2007 the FDA approved it for generic release as Zolpidem. But Ambien's hardly a perfect drug; its much-documented side effects include sleepwalking, sleep eating, even sleep sex. And a recent study concluded that regular users of sleep aids face a higher risk of cancer and heart disease than non-regular users.

Still, a 2010 study estimated that worldwide sales for sleeping pills will top $9 billion by 2015. And so, pharmaceutical companies have a massive economic incentive for supporting sleep studies that could prove to be lucrative — which means a lopsided interest in insomnia, sleep apnea (when people stop breathing while they sleep), and restless leg syndrome. The website for Harvard Medical School's Division of Sleep Medicine lists over a dozen current studies, including "Defining Phenotypic Traits In Obstructive Sleep Apnea," "Do You Have Untreated Sleep Apnea?" and "Memory Consolidation In Obstructive Sleep Apnea." "I think pharmaceutical companies dictate [what gets researched] a lot — more than I think is ideal," says Dr. Meredith Broderick, a neurologist and sleep researcher who now works at Seattle's Sound Sleep Health.

Pharmaceutical companies have undue influence over sleep research in large part because sleep research is so expensive: To keep someone in a lab for, say, a week costs thousands of dollars, so doing a large-scale, lab-based study is almost entirely out of the question. So although sleep specialists have made great strides in the last 25 or so years especially, they remain confounded by the causes of and cures for several sleep disorders that affect millions of Americans. At the moment, all of the existing medications on the market come with ominous FDA warnings about sleep-driving, sleep-eating and sleep-sex by users, who had no recollection of performing the actions after they woke up.

And in any case, Ambien isn't prescribed for people with night terrors. We have the opposite problem: We don't have trouble falling sleep — we have trouble staying asleep. But with the prevalence among adults at between one and three percent of the population, and with no clear physical cause or treatment, night terrors are low on pharmaceutical companies' priority lists. Plus, they are unpredictable, coming and going with seemingly no rhyme or reason. "It's too rare," says veteran Chicago-based sleep researcher Dr. Rosalind Cartwright, who is now 89 (and only stopped researching four years ago). So it's not surprising that scientists (and drug companies) have instead chosen to focus on ailments like sleep apnea and restless leg syndrome, which are much more easily identified and treated. The National Sleep Foundation — a non-profit funded in part by pharmaceutical companies — offers information on a number of sleep disorders on its website, including sleep apnea, nightmares, insomnia, and restless leg syndrome, but there's no mention of night terrors. They remain poorly understood and poorly researched.

Still, there are signs that sleep research could be on the cusp of some big breakthroughs. According to Broderick, until now, doctors have only been able to measure brain waves on the surface of the brain. "What we can measure is not very good," she says. "We don't do a very good job measuring deeper within the brain." But, she says, new research on epilepsy that involves putting electrodes inside someone's brain for up to a week "will help the sleep field as well. We can get more information about what's happening down there."

In the meantime, though, researchers are focusing largely on the psychological roots of parasomnias. As Broderick writes (with famed sleep researcher Christian Guilleminault) in a 2010 article on sleep terrors that appears in the first reference devoted entirely to parasomnias, The Parasomnias And Other Sleep-Related Movement Disorders:

"Night terrors often occur in patients with psychopathology, especially in adults with post-traumatic stress syndrome. Researchers have postulated that situations heightening anxiety may have an impact on hormones that causes arousal of the reticular system, which in turn heightens arousal and causes sleep disturbances. Personality characteristics have also been examined in patients with night terrors using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Their profiles were consistent with inhibition of outward expression of aggression, lowered self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and phobicness. In this study, patients with night terrors had psychiatric evaluations with a psychiatric diagnosis in 85% consisting of anxiety, depression, phobias, obsessions, and personality disorders."

Then there's Cartwright's description of the connection between the waking and sleeping brains in The 24 Hour Mind: She writes that people who sleepwalk violently often do things

that are apparently very unlike them in their conscious waking lives. They are often exceptionally good people who, while having an episode behave very badly. They strike out against loved ones, do damage to their own property, injure themselves; they eat peculiar noxious foods, are sexually unrestrained, and engage in dangerous explorations. These are all strong drives that we are taught to curb as we are socialized according to the rules of our culture. Are sleepwalkers characteristically over-controlling of basic drives, lacking the flexibility of response when some new adaptation is required? I would vote 'yes' for those I know. Furthermore, this dogged self-control, which may reach obsessive-compulsive proportions, has also been pointed out as a personality characteristic of sleepwalkers in the older legal literature.

When I speak to Richard Bootzin, a professor of psychology at the University of Arizona and head of its sleep disorders clinic, who developed a new way of treating insomnia through stimulus control in the early 1970s, I ask him point-blank why I have night terrors. "Something like night terrors can certainly start in adulthood and may have been related to a particularly bad time that you were having, a stressful time, or other kinds of psychological or emotional problems that were occurring," he says, sounding vaguely grandfatherly. "Nocturnal panic is often related to daytime panic."

These descriptions seem like — if not the answer — then at least a clue. I neither have PTSD nor, presumably, a personality disorder, and I haven't gone to such extremes as the people in Cartwright's book, but a milder version of both descriptions ring true. I've never been great about talking about when I'm stressed out, or admitting that I'm upset about something — if you've met me in real life, you've probably thought I'm a worry-free, completely content person. And so when I start telling friends about the terrors, their response is almost uniformly one of surprise. "But you always have everything under control," one tells me. Well, to some extent, sure. There's no way I can definitively prove this theory, but the idea that my suppressed anxiety is getting expressed by my brain makes intuitive sense.

When I began writing this piece — which I've been working on, off and on, for the last two years — I was obsessed with finding a cure for my night terrors, and part of finding the cure, I was convinced, was finding some kind of smoking gun that could explain neatly why I was getting them. This also seemed to be the reaction of everyone I discussed my night terrors with: If I could figure out why I got them, then I could figure out how to cure them, and their cause was probably some repressed trauma that I didn't want to confront. It seemed so potentially logical.

But in the last few months I've started considering a more mundane possibility: That things as common as a breakup, my dog dying, or stress at work are the primary causes of my sleep disturbances. It's deflating to think that there are people with what I consider real problems who are probably managing just fine, and here I am running into doors and almost jumping out of windows because of a breakup — but that seems to be my reality.

And it's a reality that seems to be shared by at least some others. In the new film Sleepwalk With Me — based on his book of the same name — the comedian Mike Birbiglia, who has had a sleep disorder for years, stars as a thinly veiled version of himself named Matt Pandamiglio. Matt is a bartender and struggling comedian in his late 20s who has violent episodes in his sleep, at one point going so far as to jump out the second-story window of a hotel because he thinks that a missile is about to hit him. In the film, Matt suggests that the stress he's under — trying to start a career as a stand-up comic and wrestling with whether he should marry his longtime, live-in girlfriend — are the precipitating causes for his sleep troubles. He eventually figures out that he has REM behavior disorder, a condition in which people act out dreams they're having, usually violently, after listening to an audiobook of The Promise Of Sleep, a book by the pioneering Stanford sleep researcher William Dement, who makes a cameo in the movie.

Birbiglia, who speaks to me from the road while promoting his film, says that while the frequency of the episodes — which started around 2004 — has ebbed, he still gets them once a month or two. After his diagnosis, he started sleeping in a sleeping bag, with mittens on so he couldn't unzip it in his sleep. Today, he still sleeps in the sleeping bag, but without the mittens — "It was like, wait, I'm in a straitjacket" — and takes medication (he declines to name which one, saying that he doesn't want people to self-medicate, but Klonopin is typically prescribed for REM behavior disorder). "It is a lot of work. It's a lot of planning," he says. "My wife and I take a lot of precautions. We're very conscious about what hotels I stay in. Everybody in my life is über-aware of this issue. We deal with it every day."

I'm struck both by the severity of Birbiglia's disorder — he could have died — and the mundaneness of its causes. Certainly, there are thousands, if not millions, of people out there who are under stress at work and at home. But they don't go jumping out windows at the La Quinta Inn. And yet, Birbiglia ends the film on a discomfiting note: "I'm not cured, but I think I'm okay with that."

No one seems to be able to answer precisely why I respond to stress by having night terrors while other people have, say, regular bouts of insomnia — but what's clear is that sleep problems are pervasive among my small anecdotal sample. (Of course, it's possible that I just have highly anxious friends.) I talk to one friend who lists the various drugs he's taken to try and deal with his insomnia: Restoril, Paxil, Ambien, Lexium, Sonata, Klonopin, Trazadone, Valium, Xanax, Vicodin. Codeine and bourbon. AdvilPM. Nothing worked until he started seeing a cognitive psychologist. Another tells me that she's taken Ambien for years, and now can't imagine falling asleep without it. Yet another tells me that she'd been going through a particularly stressful time — she recently broke up with her boyfriend — and has been getting less than four hours of sleep a night. And yet another says that her sleep is usually broken up in chunks — she'll sleep for a couple of hours, then be awake for awhile, then fall back asleep for a short period. There is likely a genetic factor at work — my dad says he talked in his sleep as a child and young adult, but neither he nor my mom say they sleepwalk — but still, I don't know why neither of them has night terrors, or why Mike Birbiglia has REM behavior disorder or why Tobias Wong chopped up vegetables for a cricket. I ask Cartwright, and her response is: "That's a very good question, and it's not being handled well at all." Neurology seems great at figuring out the whats, but not the whys.

The message board on NightTerrors.org — one of the few sites devoted to people with night terrors — has a post that's been viewed over 122,000 times titled "Specific Triggers For Night Terrors." It lists seven categories — Stress And Anxiety; Temperature; Disruption Of Sleeping; Sleeping Environment; Eating And Digestion; Medications, Drugs And Alcohol; and Hormonal Changes — that this poster claims contribute to night terrors. Each of the categories has several specific triggers listed. I read the list with growing dismay. It seems impossible that anyone would ever be able to avoid all of these things, particularly in New York: "Sudden noise at night (windy nights, traffic noises, banging sounds, creaking floor-boards)." "Anxiety." "Chaotic sleep schedule." "Negative thoughts (about Night Terrors, financial worries, going on vacation)." In mid-August, I go on vacation with a couple of friends. It's probably not coincidental that I have the best sleep I've had in months.

As I finish this article, I'm still not "cured," and it seems increasingly likely that I'll have to come to terms with some degree of accommodation with it, much like Birbiglia. But the nights where I wake up in full-panic mode and in the morning, see bruises from where I ran into the side of my bed or crashed into my closet door are becoming fewer and farther between. When I do get a night terror or start sleepwalking, I'm usually able to wake myself up in the middle of it; I've noticed that I'll often realize that whatever the particular terror I'm having isn't real before I'm able to actually wake up. I have felt the physical sensation of part of my brain struggling to overcome another part of my brain.

The last few months have been especially panic-free. While I can't point to one particular change that's made them less frequent, I suspect that a combination of factors has helped. Working on this piece has, perhaps not surprisingly, brought me a degree of calm. It's felt good to relieve myself of this psychological burden, to talk about it with people who are familiar with what I've gone through. I've also modified my sleep behavior, and I now try to be asleep (not just in bed, but asleep) by midnight, and preferably 11:30. It's a small adjustment — I'm probably getting under an hour of extra sleep per night — but it seems to have made a difference. Also, I started going to therapy, and even though my therapist doesn't have a specialty in sleep disorders (and in fact seemed rather alarmed when I told her about the terrors), having this outlet has been helpful. I have a job that I love. And maybe most important, I've grown more comfortable with simply talking about when I'm under stress. I want to express it on my own terms — when I'm conscious.

But they still happen occasionally, and not always under the most ideal circumstances. A few months ago I suddenly wake up, and scream something, and the guy I've been seeing — it's not serious, and so I've never exactly found the right moment to casually mention that I have a sleep disorder (though from now on, anyone I date will be all too aware, I realize) — also wakes up, completely startled. "What was that?" he asks, seeming panicked.

"Oh," I say. "Bad dream." And I roll over and go back to sleep.