Massachusetts Puritans once blamed witches for the trances and strange utterances of young girls in Salem Village.

More than 300 years later in the same town, now called Danvers, state health officials investigated a mysterious 2012 outbreak of chronic hiccups in 24 teenagers, mostly girls, at two local high schools. After two years of studying possible environmental factors — in the schools’ water fountains, air vents, and sports fields — the state came up with no real explanation.

Among former students, opinions vary widely.

"Some massive inside job perpetrated by our U.S. government," Theenith Chroek, a 21-year-old former student who now lives in Lynn, Massachusetts, told BuzzFeed News over Facebook messenger. “The government or at least the 'real' government is working on a new biological weapon.”

"Why or how it happened isn't too big of a concern for me," said another, 21-year-old Jeremy Cronan, who now lives in the UK. “I heard rumored that it was one case of the vocal tic and the rest of the group of ladies that caught it were more mentally [affected].”

A researcher in New Zealand broadly concurs with the latter idea, using a more precise term: “psychogenic conversion disorder” — a condition typically seen in teenage girls in which psychological stress turns into real physical symptoms. After making public records requests for state documents, sociologist Robert Bartholomew discovered that the Massachusetts investigators had also suspected that this stigmatized disorder (once known as “mass hysteria”) was the culprit. But they never disclosed it to the public.

“What I can say for certain is that the Massachusetts health department knowingly issued an inaccurate, incomplete report,” Bartholomew told BuzzFeed News by email. “They have an obligation to issue accurate diagnoses, and patients have a right to know what made them sick.” He has filed medical malpractice complaints to both state and federal officials.

Documents released to Bartholomew last year show that state officials considered a group psychological phenomenon early on in the outbreak. By stalling and avoiding that conclusion, Bartholomew contends, they were hoping to avoid the notoriety that attended a similar twitching outbreak in Le Roy, New York, a year earlier, where doctors made the diagnosis plain.

Although widely assumed to be a mental illness, conversion disorder is actually a group reaction to stress.

But burying this diagnosis just keeps its stigma alive, Bartholomew said. Although widely assumed to be a mental illness, conversion disorder is actually a group reaction to stress.

"There is a popular perception that victims of ‘mass hysteria’ are somehow weak-minded or suffering from a mental disorder,” he said. “This perception needs to change, and I believe it begins with public health officials investigating these outbreaks.”

He and other experts emphasize that patients aren’t faking their symptoms, and that this should be formally recognized.

“These patients are really suffering, it’s important to say that,” University of Rochester Medical Center neurologist Jonathan Mink, who investigated the 2011 episode in Le Roy, told BuzzFeed News.

When asked why it did not publicly acknowledge that a group stress reaction explained the outbreak, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health said that would have gone beyond the scope of its investigation.

“The purpose of the study was to look for potential environmental factors contributing to vocal disorders in some students at the two schools; not to provide a diagnosis for the conditions that some of the students were experiencing,” Scott Zoback, a representative of the department, told BuzzFeed News by email.

BuzzFeed News reached out to more than 70 students who attended the two affected high schools during the 2012 outbreak. Just four responded, perhaps attesting to the stigma surrounding the case.

Chroek's conviction of a massive government conspiracy is not at all surprising, Bartholomew said, when public health officials leave the cause of an outbreak up in the air. “I think the manner in which the case was handled has only served to feed this kind of social paranoia.”

The outbreak began, in August 2012, with one boy at North Shore Technical High School in Middleton, Massachusetts, who had “vocal tics and chronic hiccups” that wouldn’t go away. That school’s principal later reported “a handful of incidences” that came and went before the holidays.

Within weeks of starting, the tics had also spread to a sister school, Essex Agricultural Technical High School in Danvers (the two schools later merged).

“The tics were described as hiccups, grunts and yelps,” Bartholomew wrote in a Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine report earlier this year. The episodes seemed to peak in September and were still affecting 19 students at both schools in November, when the investigation began. Most of the students were on sports teams.

The two technical schools, which drew students from dozens of communities in the northeastern part of the state, held carpentry shops, a horse barn, and a cosmetology salon. As word of the vocal tics first spread, airborne toxins were immediately suspected.

“Before this whole thing got started, I remembered smelling something distinct in the air. It was almost some sort of Febreze scent,” Chroek said. “I didn't think much of it at first but the smell stayed in the air even hours later. That’s maybe around the time all of the hiccups started.”

Some parents, meanwhile, believed the culprit was PANDAS (or pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections). This controversial diagnosis, which is contested by some medical researchers, is thought to begin with a strep infection that triggers an immune reaction in the brain that can cause neurological tics.

By Christmas Eve, the state’s environmental health chief medical officer, Jonathan Burstein, was circulating articles about mass psychogenic illness to other investigators, the records show. But when a Boston Globe reporter contacted a Danvers official the next month, he was told that no “confirmed” cases had been reported and was discouraged from writing a news story.

“To some extent this is very normal human behavior. Look at how yawning can become contagious."

State health officials investigated vents in the schools, queried 2,600 local doctors about symptoms, and peeked into two abandoned tunnels under one school’s grounds. They also conducted three environmental assessments over three months, looking for mold, asbestos, mercury, carbon monoxide, and other pollutants at the school that might have triggered neurological symptoms. They found nothing.

The investigators worked on their report for two years. Bartholomew is sympathetic to officials not publicizing any psychogenic suspicions initially, particularly with parents of some students complaining they were being harassed. But the records show that Burstein compiled a list of possible culprits in the outbreak and found them all highly unlikely — except one. “It is not possible,” he wrote, “to rule in or rule out the possibility of any conversion or mass psychogenic factors.”

The official report, however, doesn’t mention this diagnosis. ”[T]he crude prevalence estimate for the students with confirmed vocal tics/chronic hiccups at the schools is estimated at 1%, which appears consistent with prevalence estimates for tic disorders,” the report concluded.

In other words, according to the state’s report, tics just happen sometimes. The outbreak was an explainable statistical fluke, a happenstance of hiccups, grunts, and yelps, in numbers you might reasonably expect.

Medical records did show that one student had three years earlier been diagnosed with Tourette syndrome, marked by random vocal outbursts, and two others had been previously diagnosed with vocal tics.

But Bartholomew said the 1% prevalence estimate for tics is bogus. The number came from an investigation of vocal tics in 4,479 Swedish schoolchildren, he pointed out, which actually concluded that among teen girls, only 0.15% have vocal tics. He believes the 1% argument is a fig leaf for state officials walking away from the whole mess.

Diagnosing group psychogenic outbreaks is trickier than diagnosing a virus or infection, Mink said, because you can’t run a simple test for it. But he agrees that the Massachusetts case was a likely one.

“To some extent this is very normal human behavior,” he told BuzzFeed News. “Look at how yawning can become contagious. We pick up on other people, it’s part of the human condition.”

At least one parent came to this conclusion, too. In an email sent to a public health official just after the final report came out, the parent wrote that their child’s symptoms had been gone for more than a year, adding: “Our initial suspicion of conversion was probably correct.”

With the rise of Facebook and other social media that connect teenagers in new ways, group stress disorders might spread more widely now, some medical sociologists say.

For example, the similar outbreak in Le Roy, which Mink helped investigate, partly spread through people connected only by Facebook. “We’re actually doing a disservice by avoiding making a definite diagnosis and perpetuating that this is mysterious,” he said.

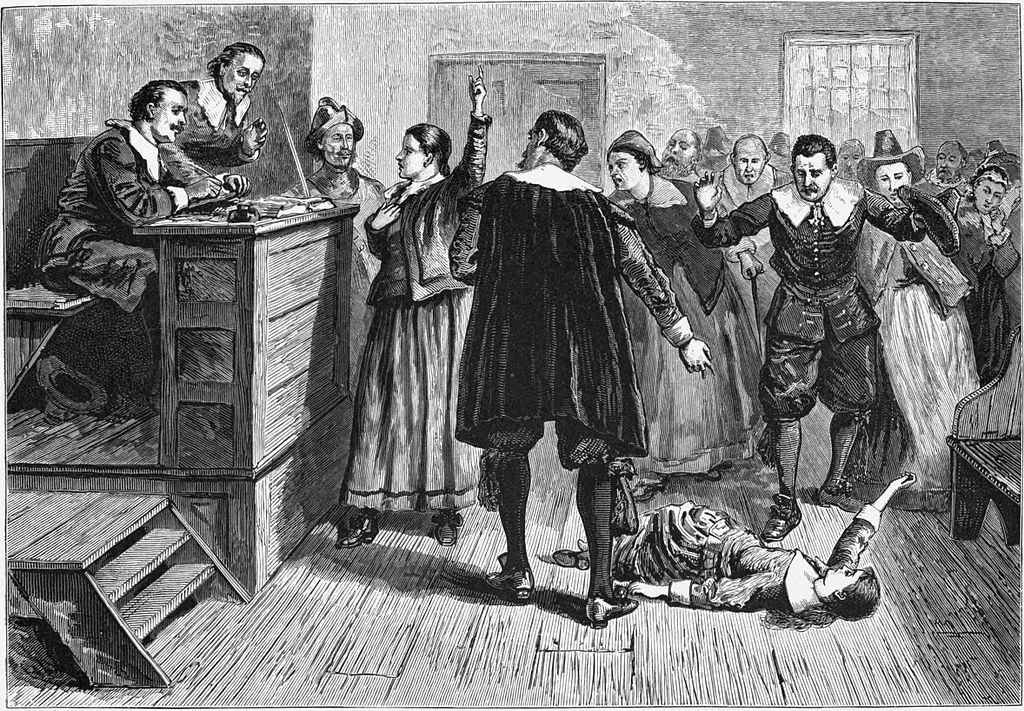

Three centuries ago, a similar outbreak appeared in this same Massachusetts town, with tragic consequences. In the winter of 1692, seven girls in Puritan Salem Village began contorting, twitching, and uttering unintelligible noises. Some complained of being bitten and pinched by witches and devils.

The resulting Salem Witch Trials, variously ascribed to mass hysteria, hallucinogenic bread, or greed for the property of the accused, led to 20 executions for consorting with the devil. They ended a year later, with apologies from some, but not all, of the ringleaders. The trials have resonated in the public imagination for centuries and turned Danvers into a tourist destination.

In hindsight, according to Bartholomew, it’s clear the Salem Village girls were suffering from some sort of group conversion disorder.

Psychogenic illness seems to be most common in distressed communities: Salem Village in 1692 had recently lost in a conflict with Native Americans, filling the town with refugees. Le Roy, New York, was reeling from the 2008 economic downturn. Danvers didn’t seem to have economic stress (the unemployment rate there was 5.4% at the time of the outbreak), other than the coming merger of the two schools, but there doesn’t always need to be a stark conflict to trigger an episode.

Psychiatrist Simon Wessely of King’s College London agrees that the Massachusetts students likely suffered from a group psychogenic disorder. But unlike Bartholomew, he endorses the state’s silence on that diagnosis, saying it’s better to let these episodes quietly fade from the news instead of creating a national sensation similar to the 2011 Le Roy outbreak. In that case, he points out, some students’ tics persisted far longer than usual, perhaps because of the diagnosis and media scrutiny.

“It’s a very difficult situation for public health officials to handle,” Wessely told BuzzFeed News. “When it is over, [the students] get better, and the symptoms generally don’t come back.”

It’s also worth noting that not every scholar who has looked at Le Roy is convinced that mass psychogenic illness was the right diagnosis there. Last year, for example, two University of Colorado Boulder anthropologists argued in American Ethnologist that Le Roy investigators gave short shrift to toxicological explanations for that outbreak.

Regardless of their cause, you only have to look back to the Salem Witch Trials to see that these outbreaks are long-standing afflictions of humanity, Wessely said. “They happen all the time, probably more than we know. The best thing is to handle them as calmly as possible.”