The Renaissance Blackstone Hotel in Chicago, way back in June 1920, famously birthed the concept of the "smoke-filled room" when a gaggle of Republican power brokers checked into a suite and stayed up all night, puffing their lungs black and haggling over their party's stalemated presidential convention. (They ultimately decided on nominating Warren G. Harding, a devoted tobacco user in his own right.)

So it seems appropriate that on Thursday night the hotel served as the setting for a marijuana powwow — more specifically, the Illinois Medical Cannabis Investment and Legal Seminar.

Looking not all that different than the attendees of an insurance conference, a crowd of around 50 mostly white, middled-aged men in sports jackets — each of whom paid several hundred dollars for entry — sat at long tables with water pitchers and information packets in the hotel's "Innovation Room" to hear Brian Vicente and Christian Sederberg provide three hours of tips and intuition about navigating the legal and financial obstacles to starting a medical marijuana dispensary.

Or rather, a medical cannabis company — the first rule of marijuana club is not to talk about "marijuana." The nomenclature is important, insists Vicente, the Colorado lawyer who helped lead the successful fight to legalize pot in his home state. You don't dick around.

"This isn't a reefer shop. This is Chicago's Wellness Center," he says. "It is the best way to keep the federal government, soccer moms that might complain, and law enforcement from beating on your door."

Vicente and Sederberg have become two of the more prominent voices on marijuana — sorry, cannabis — legalization in the last year. Their law practice, Vicente Sederberg LLC, now operates as a "full-service medical marijuana law firm," with offices in Denver and Massachusetts, and plans to expand.

The legalization effort, as it continues to push forward, needs an industry to support it, just as it finds a phalanx of aligned corporate interests (lobbyists, drug-testing equipment manufacturers, DEA subcontractors, etc.) in opposition. There is for-profit potential here. But it's not going to be easy.

"When you are planning your business, you have to understand that this is a federally illegal product," Vicente says. He notes that there are former dispensary owners who currently sit behind bars, looking at another decade of hard time.

Even if you don't get shut down and carted off by the feds, you still will constantly bump up against Uncle Sam's presence, particularly when it comes to banking and taxation. Banks tend to become tight-fisted with loans and credit for this type of business. Vicente tells of one client in Colorado who has had to open up 14 different bank accounts over the last 11 months.

Presuming you're able to get a loan and open a business and make money dispensing, current federal law makes simply depositing it an enterprise unto itself.

Section 280 E of the Internal Revenue Code — which everyone quickly scribbles down on their notepads when Vicente mentions it — holds that no deductions or credits shall come from the "trafficking" of federally prohibited substances.

"This is a brand-new industry," Sederberg says, "so a lot of people think that it is an immediate moneymaker because it is a product everyone wants, and [they think] there is a large margin for error when there really isn't."

As Jill Lamoureux, who previously operated four dispensaries in Colorado and now works as a consultant and grant writer, declared to the attendees upon taking the podium last night, medical cannabis is "one of the riskiest businesses you could ever undertake." The margins are small and the payback period is long. In Illinois, specifically, patient protection laws are limited, making setting up a dispensary even riskier than in Colorado, Lamoureux notes.

To make the point even finer, she compares the prospective endeavor to her former career in the world of municipal bonds, saying, "It is probably easier to sell junk bonds for construction projects in South America than it is to be in this business."

She advises arming oneself with multiple attorneys and a "great tax advisor."

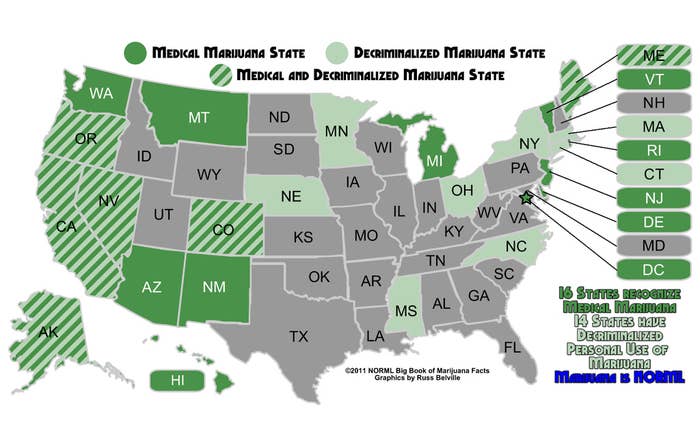

Earlier this month, Illinois became the 20th state in the nation to sign into law a medical marijuana bill, although a rather difficult one, as plainly evidenced by its full statutory name: the Compassionate Use of Medical Cannabis Pilot Program Act. The operative word being "pilot," as in trial; the law will be up for renewal in 2018.

And even though the legislation is 200 pages long, many of its specific provisions are still waiting to be hashed out. So far we know only that there will be tremendous bureaucracy: Dispensaries will be regulated in Illinois by four executive agencies. And there will be a long delay. The Department of Agriculture has announced that it doesn't expect to accept dispensary applications until fall 2014, meaning that patients likely won't be able to start getting cannabis until early 2015 at the earliest. To put it another way, a prospective dispensary owner could spend the next two years hazarding a thicket of red tape in trying to set up a business, with only the guarantee that the pilot law will be in effect for the three years after that.

"You've got to take the long-arc view on this. Marijuana was illegal for 80 years, and now it is becoming a regulated product," he says. "We are trying to get on the ground floor. It may take months, it may take years to get established."

For now, the pot of gold is as ethereal as a rainbow. You need so much capital and so much patience and so much gumption. And at the end of a sobering walk through the legal and financial hurdles to climb to get into the medical cannabis business, you know what else you can really use?