The outcome of Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, a case heard by the Supreme Court on Monday, will have profound implications for the American union movement, and particularly those representing government employees.

If the court rules against the unions — and in oral arguments today, it appeared this is a likely outcome — it will be another nail in the coffin of the union movement. Pro-union publications are freaking out: The American Prospect called the case a looming mega-attack "designed to decimate" organized labor, and In These Times called it "the stuff of a vast right-wing conspiracy."

The court is expected to make a decision in the case by June. Should the Justices rule "fair-share" dues illegal (more on this below), unions stand to lose a staggering amount of money and power, very quickly.

The only upside, according to some in the movement: the loss could galvanize both labor leaders and the rank-and-file, leading unions to return to their origins with new urgency in the midst of crisis — or reinvent themselves entirely.

Here's what you need to know about the case.

"Fair-share" dues are fees required to be paid to unions by workers who have opted not to join the union. Those workers still benefit from the collective bargaining and grievance representation provided by the union, the logic goes, and so should therefore be required to pay their fair share.

The fees are lower than regular dues, which also cover union political activity. In a 1977 case, Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled that workers can't be required to join a union, as that would violate a First Amendment right to freedom of speech and association (by requiring workers to, well, speak and associate). But the court also ruled that unions have the right to collect fair-share fees, which cover the costs of union activity that benefits all workers.

That money cannot be spent on political activity, as per the ruling, which would violate workers' First Amendment rights.

In the 2014 case of Harris v. Quinn, however, Justice Samuel Alito signaled in his majority opinion that the conservative justices would be open to questioning the constitutionality of the Abood precedent, which has previously been upheld at least four times. These hints led to the filing of Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, which has been backed financially in part by right-wing groups such as the Center for Individual Rights.

The plaintiffs in the case that will be heard Monday are ten California schoolteachers, including Rebecca Friedrichs (along with the Christian Educators Association International), who have chosen not to belong to the California Teachers Association (CTA), and who are suing to be relieved of fair share dues.

The defendants are the National Education Association, the country's largest teachers' union, and the CTA.

The plaintiffs argue that any form of collective bargaining with the government is inherently political, and therefore requiring payment in support of it is a violation of their First Amendment rights. Should their argument succeed, workers covered under public-sector union contracts could legally stop paying dues or fees, and unions would have to organize (i.e., sign up members again) to collect future payments. This would take time and money — both of which are in high demand among unions, particularly in the lead-up to the 2016 elections.

Why should you care?

The public sector is the last major stronghold of the union movement in the United States. Government workers have a union membership rate of about 36%, more than five times that of private sector workers. (Altogether about 11% of America's workforce, or 14.6 million people, belong to unions.)

A ruling giving workers a "free ride" on the benefits obtained by dues-paying union members, could create a legal opening for public-sector workers to split into competing factions of union and non-union groups, at odds with one another during negotiations with management.

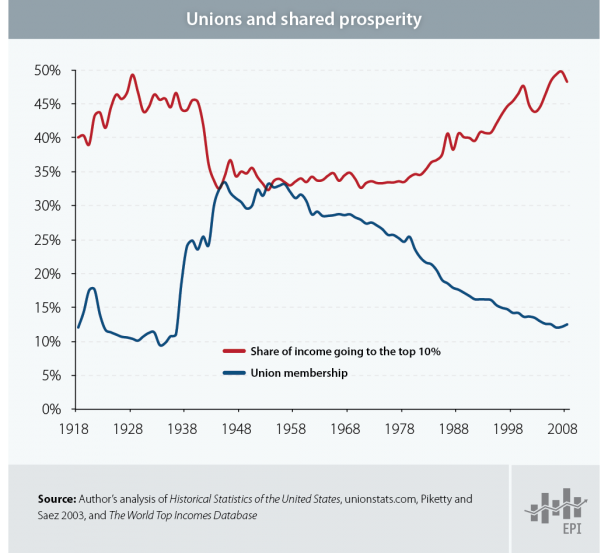

This, in turn, could reduce the bargaining power of unions in pay negotiations. Liberal-leaning economists and think tanks often point out that in the last 50 years, economic inequality has risen in tandem with the decline of union membership.

A bellwether state?

Recent events in Wisconsin, which famously had its public-sector unions decimated under Governor Scott Walker, may offer some reason for hope for those in the labor movement.

Wisconsin's unions could "point the way for public-employee unions nationwide if the supreme court ... prohibits any requirement that government workers pay any fees to the unions that represent them," former New York Times labor reporter Steven Greenhouse wrote in The Guardian earlier this month.

The Wisconsin branch of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) union lost two-thirds of its members and revenue after the Republican-controlled state legislature enacted Gov. Walker's anti-union bill, Act 10, in 2011.

The Act, which in many ways is even more punishing to unions than the Friedrichs ruling would be, eliminated any requirement that government workers pay union fees while also prohibiting government agencies from collecting employee dues on a union’s behalf. The law further required public-employee unions to hold annual elections to determine whether a majority of all workers in a bargaining unit want to belong to a union, before the union could bargain collectively.

As a result of the stringent and expensive new requirements, AFSCME subsequently gave up bargaining for many public employees in Wisconsin. But in an effort to stay financially afloat, it also undertook an aggressive new organizing effort, and has since said it has increased its membership by 150,000 in the past two years.

“When we talk to potential union members, we explain, 'your working conditions aren’t going to get better unless we act as a unit, as a union,’” Paul Spink, President of the Madison-based AFSCME branch told Greenhouse. “We have to relearn the lessons of labor from the 1930s and 1940s – of collective action and collective message.”