Three months before National Guardsman Ryan Anderson was scheduled to deploy to Iraq, he posted a message on the internet forum Brave Muslims.

“Just curious, would there be any chance for a brother who might be on the wrong side at the present, could join up...defect so to speak?”

Halfway across the nation in Montana, a vigilante judge posing online as a radical Muslim flagged the message to federal authorities, setting into motion an undercover investigation, Anderson’s arrest in Washington state, a court-martial, and a life sentence in prison.

Prosecutors framed the case as a treasonous plot, another potential radicalized fighter foiled. But more than 10 years after his conviction, Anderson maintains it was more a misunderstanding fueled by mental disorders that made it impossible for him to keep from going over the cliff.

The person recorded in undercover videos, the emails, the text messages that amassed into a terror conviction, were of a “totally fictitious individual who I invented to avoid the truth,” Anderson said, reflecting publicly on his conviction for the first time to BuzzFeed News.

"Make no mistake about it: I lied my way into prison.”

It was Nov. 2, 2003, a time when two U.S. military helicopters came under fire in Iraq and 16 soldiers were killed — the deadliest attack on American troops since the invasion began months prior — when Anderson made the post on the Brave Muslims forum referring to defection.

Six months earlier, President George W. Bush had famously delivered a speech on the USS Abraham Lincoln in front of a banner that declared “Mission Accomplished.” But Saddam Hussein remained at large, the conflict had not ended, and Anderson’s National Guard unit was among those preparing to deploy to Iraq.

Anderson, who had trained to work as a tank crewman, would be overseas for a year in the infantry — and that rankled him.

“I was ordered to go to a country that we had initiated a questionable war with, in a capacity that I had not volunteered to serve in."

“I was a National Guardsman with less than an aggregate total of eight months time actively in service, including basic training,” he said in his correspondence with BuzzFeed News. “I was ordered to go to a country that we had initiated a questionable war with, in a capacity that I had not volunteered to serve in.”

Using the names Al Muj and Amir Abdul Rashid, his postings on Brave Muslims — in which he vowed to “take my own end of the struggle against those who would oppress us, to the next level” — caught the attention of another user also using a false identity.

Shannen Rossmiller, a municipal judge from Montana, would go on to make a name for herself posing as a radical Muslim in her vigilante effort to smoke out potential domestic terrorists.

About a month after she and Anderson began exchanging emails, Rossmiller alerted the FBI. The undercover investigation moved quickly.

By that January, Anderson had begun unwittingly exchanging texts with an Army intelligence agent. On Feb. 8, 2004, after about 15 conversations, Anderson met the agent at a Barnes & Noble and in a show of good faith handed over a floppy disk containing his passport photo. He also relayed schematics of an M1A1 Abrams tank, although they were based on information from an unclassified website.

The next day, Anderson met the agent and another man at a parking garage in downtown Seattle. The unknown man, another intelligence agent, posed as an al-Qaeda operative who could guide Anderson’s future activities.

"What organization do you think we are?" one of the men asked.

"I believe you are what Americans call al-Qaeda," Anderson replied.

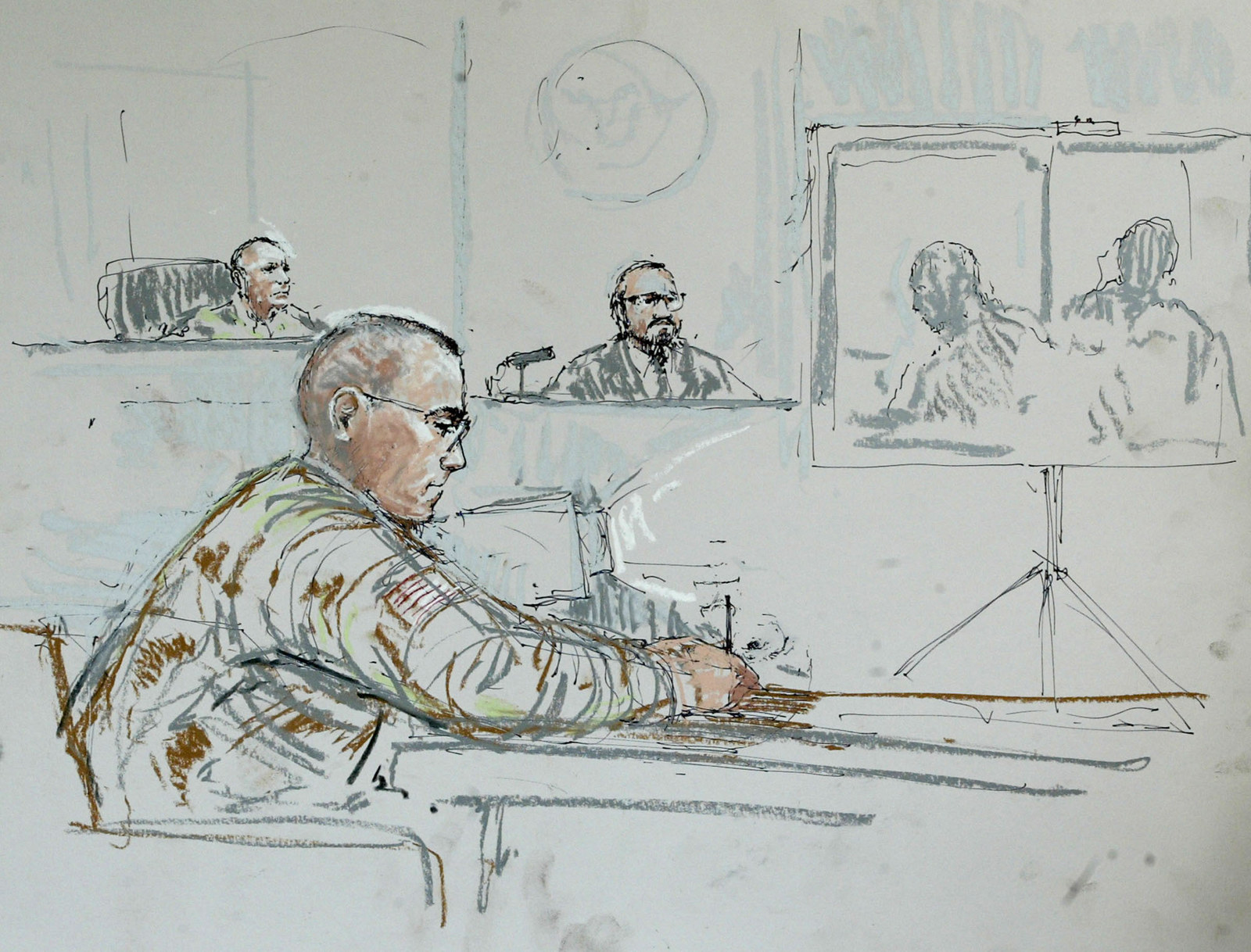

The hourlong encounter was recorded on a hidden camera, which was later played at court proceedings and reported by local media.

At one point, one of the agents asked about armored Humvees, and Anderson pointed out the vulnerability of their windshields.

"It would be very easy to kill a driver, or the crew inside," he said.

Americans, he added, weren’t worth his dying for.

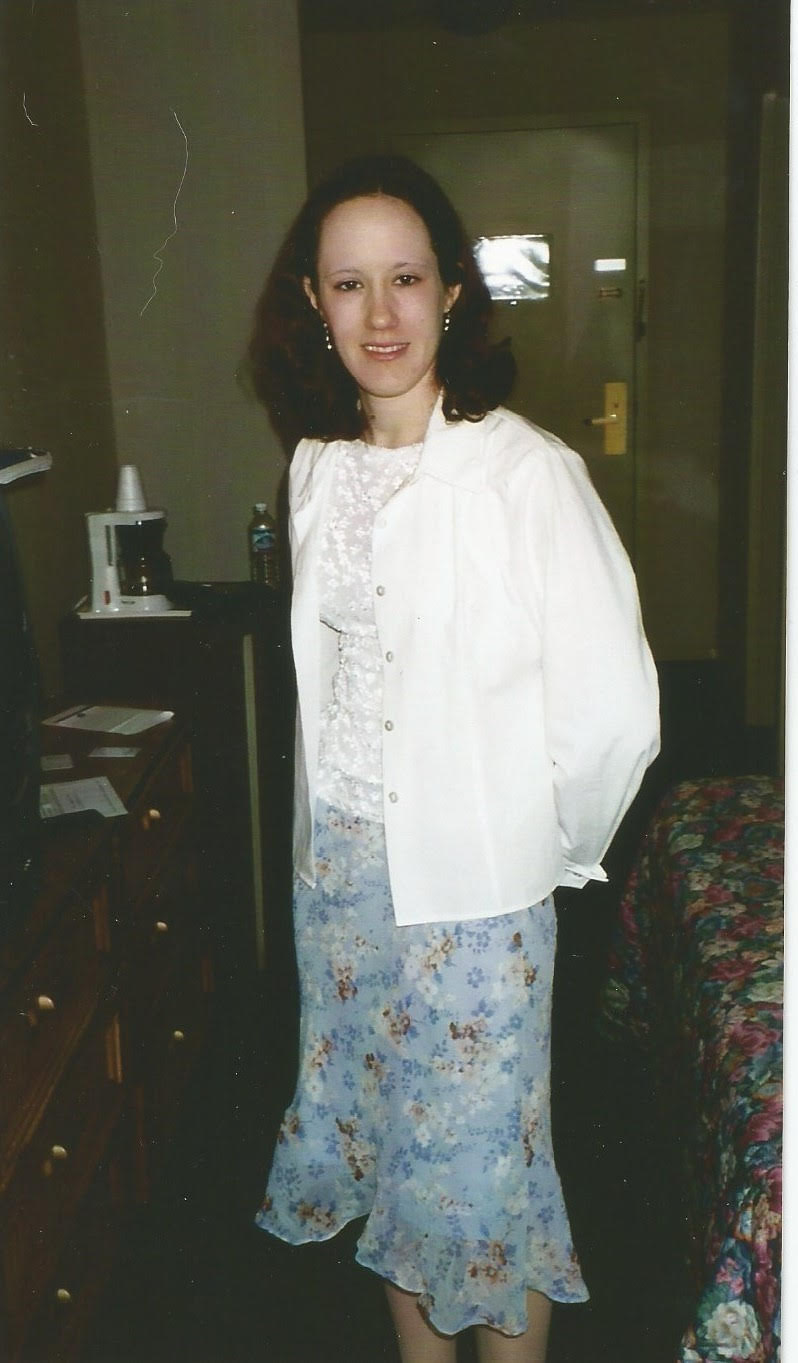

Erin Anderson found out about her husband’s arrest a few days later, on Feb. 12, when agents banged on her door at 7 a.m., pulled her outside, and started searching their home. She was released after two and a half hours of questioning.

“I had absolutely no fucking clue what happened,” she told BuzzFeed News.

Neither, really, did Ryan.

The day after meeting with the agents, he went to talk about the encounter with his superior officer to see if anything was amiss. Not long after, he was taken into custody.

“I thought the people arresting me were there to help me,” he said. “Let me be entirely candid and say that I wasn’t feeling all right at the time, and I wasn’t thinking clearly. I’d said a lot of crazy things to a lot of people, but I didn’t expect that I was going to get thrown to the wolves like that.”

At his trial — a portion of which was held in closed session to protect potentially sensitive or classified information — defense attorneys suggested that the information Anderson had shared with the undercover agents was nothing new. Most of it was readily available on the internet and already included in al-Qaeda training manuals, his attorney said.

Even one of the agents involved in the undercover sting testified that Anderson had made wild exaggerations, told lies, and “jabbered” for much of the meeting in the Seattle parking garage.

Still, on Sept. 3, 2004, a jury of nine Army officers convicted Anderson on five counts of attempting to provide information to a terrorist network.

Anderson said he never really believed the agents were al-Qaeda operatives but couldn’t stop role-playing due to his bipolar and autism spectrum disorders. During his sentencing, a clinical psychologist appeared to back that logic up, telling the court that Anderson “resorts to role-playing” for structure and emotional control.

Anderson is not alone in his place among terrorism collaborators falling on the autism spectrum.

Adam Dandach, a 21-year-old from Southern California, told BuzzFeed News in jail cell correspondence that he has autism but earlier this year decided to plead guilty to attempting to provide material support to ISIS.

“I am far from a criminal or terrorist,” he said. “I am a young autistic man who can barely tie his own shoes being held as a political prisoner. I have never lived a life of crime or terror, nor will I ever.”

Anderson’s path to a potential lifetime in prison started in Everett, Washington, a city of about 100,000 people 40 minutes north of Seattle on the Puget Sound.

He was an awkward kid — obsessed with airplanes and other military hardware, but unable to quite follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather's military accomplishments. He was disqualified from becoming an Air Force pilot due to his eyesight, he didn't have the physical ability to make the high school football team, and at one point he was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder.

He also often failed to grasp how others might see his actions, such as the time in 1998 when he walked past a school carrying an 1880s-era French rifle, complete with a bayonet. It was the day after a now infamous school shooting in Oregon left two dead and 25 wounded, and an alert neighbor called sheriff’s deputies, who confronted him with guns drawn. Anderson had been walking to a friend's house to do some repair work on the rifle — he didn't see what a shooting done by someone else in another place had to do with him.

When he graduated high school in 1995, a local newspaper reported his yearbook quote as reading: “Have a (expletive) great summer. Let's overthrow the government!"

The Star Trek and Star Wars fan went on to Washington State University, where he spent time in an online forum for a right-wing militia group. Teachers told the Seattle Times they didn’t remember him as a good student, although he found a new obsession in the study of Asian history — Japan, China, and eventually, the Middle East, and Islam.

“I spent almost an entire year studying Islam in school and began to feel a real call to it as a…system of belief,” Anderson told BuzzFeed News.

“I firmly believe that being arrested saved my life."

His study of Islam continued until finally, in fall 1999, he walked into the modest mosque in Pullman, Washington, where shortly before Ramadan, he declared the shahada, the testament of faith.

After graduating in 2002, Anderson began working in private security and joined the National Guard.

His mother would later testify that though she could never imagine her son as an active-duty officer, navigating combat or leading other soldiers, she saw the Guard as a good fit.

"I thought he would be good at helping people,” Linda Tucker told the court. “I thought in floods or whatever, Ryan would be awesome.”

In April 2003, halfway through his basic training in Kentucky, his college sweetheart, Erin, visited and the couple eloped. But newlywed bliss was short-lived. He was staying up for days on end, she said. He was bad with money. He’d spend his nights drinking with the guys.

After telling an Army health worker that he was depressed, Anderson was given an antidepressant that he now believes pushed him into a manic phase of the bipolar disorder that at the time was still undiagnosed. Erin couldn't explain his erratic behavior, ups and downs, and intense focus at the expense of other things.

“I was very frustrated,” she said. “I wanted him to grow up, and he wasn’t growing up.”

But as preparation for his trial began, Erin told BuzzFeed News that her husband’s mental health evaluations started coming back, describing symptoms she had long seen but didn’t understand. That’s when she embarked on her own study of mental illness and autism spectrum disorders.

“I started seeing, ‘Oh my god, this is Ryan,’” she said. “It just started explaining everything.”

But it was too little, too late.

The routine and explicit rules of prison life haven’t been all bad for Ryan Anderson. All things considered, he said he's been treated well. Along with access to books, movies, and a word processor, he runs several role-playing games with other inmates.

It's also been a time of intense personal growth.

“I firmly believe that being arrested saved my life,” he said.

Had he deployed to Iraq in his manic state, it’s likely he would have acted recklessly in combat, possibly hurting or killing not just himself but his fellow soldiers. Anderson and his wife also believe that his time in prison — and the focus and introspection it brought — saved their marriage.

“He never actually did anything. Nobody was hurt. There were no victims."

“I’ve got nothing to be ashamed of for who I really am,” he added. “I just wish I knew that earlier and could have accepted it.”

But while her husband attributes his court-martial to a faulty military justice system, Erin sees other motives.

The Army, she claims, couldn’t admit they had allowed someone so mentally ill into a uniform. Not only that, he was a Muslim.

“They wanted to make an example,” Erin said.

In the intervening years, Erin — a social worker who has since converted to Islam — has been placed on a no-fly list, and her home has been searched by authorities. She was never accused of committing a crime.

While her husband could be up for parole in four years, Erin's also mindful that it could be much longer. And that, she says, is unfair when others who have killed, abused, or admitted to betraying the U.S. serve less time.

“He never actually did anything,” Erin said. “Nobody was hurt. There were no victims.”