The use of an experimental serum to treat two Americans who contracted Ebola in Liberia, has raised a number of questions about whether others infected with the virus should be given the medicine.

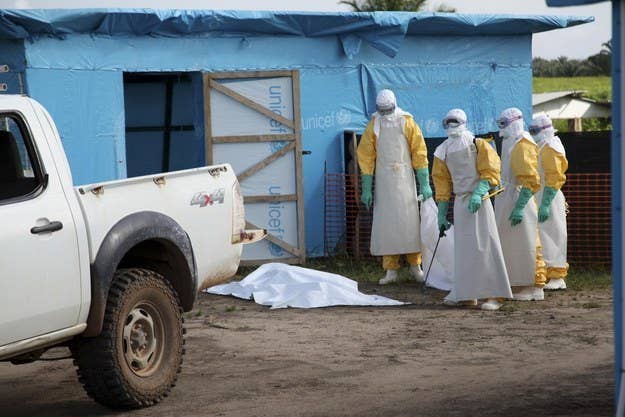

The World Health Organization said Wednesday that medical ethicists will meet next week to discuss using the experimental treatment in West Africa, where more than 900 people have so far died from Ebola. More than half people who have contracted the disease this year — for which there is no approved medicine or vaccine — have died, according to WHO.

Americans Nancy Writebol, 59, and Dr. Kent Brantly, 33, who had been working in Liberia with an international aid organization, were given the experimental serum before being transported to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

While Emory officials have not commented publicly on the patients' conditions, but the use of the drug protocol for Writebol and Brantly has raised some hope despite the fact that the drug had not been tested in humans. In a statement about next week's meeting, WHO also noted there are questions "given the extremely limited amount of medicine available, if it is used, who should receive it."

"We are in an unusual situation in this outbreak. We have a disease with a high fatality rate without any proven treatment or vaccine," Dr. Marie-Paule Kieny, WHO assistant director-general said in a statement. "We need to ask the medical ethicists to give us guidance on what the responsible thing to do is."

ZMapp, a serum created by California and Canadian pharmaceutical companies with collaboration from both countries' governments, contains human versions of antibodies found in the same plant classification that contains tobacco, according to a Mapp Biopharmaceutical document.

"ZMapp is being developed as a therapeutic product for treatment of people infected with Ebola virus, but not to prevent infection in the same manner as a vaccine," according to the Centers for Disease Control.

It was named a drug candidate in Jan. 1, but it has not been tested for safety in humans, the company and the CDC said.

"Any decision to use an experimental drug in a patient would be a decision made by

the treating physician under the regulatory guidelines of the FDA," the company said.

Before being approved for human use, drugs first go through small, then large-scale trials. The FDA makes an exception, however, for patients with serious or life-threatening conditions where there are no alternative treatments.