WASHINGTON — A 4-4 split Supreme Court on Tuesday left in place a lower court ruling that allows public unions to collect fees from non-members.

After arguments in January, it had appeared that a 5-4 court was going to strike down so-called "agency fees," but the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February upended the case.

The decision marks a victory for unions that was completely unexpected when the Supreme Court agreed to hear Rebecca Friedrichs' case this past June, and the strongest sign yet of the changed composition of the court without Scalia.

The Supreme Court had allowed for such fees in a 1977 decision that the unions had argued was now a settled part of the American workplace landscape, but the court in a recent case had signaled that it was open — if not eager — to reconsider that ruling.

In November 2014, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld such fees administered by the California Teachers Association under the 1977 case, Abood v. Detroit Board of Education. Two months later, Friedrichs asked the Supreme Court to reverse Abood and end "agency fees" in public unions.

The case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, was considered almost a done deal when the court agreed to hear the case, given the comments from the five-justice conservative majority of the court in 2014 in Harris v. Quinn. The arguments in Friedrichs bore that out, with the five justices appearing poised to end the fees.

Friedrichs argued that the First Amendment bars California from forcing her to pay money to a union with which she disagrees and has chosen not to join. The unions, joined by California and the Obama administration, countered that the 1977 decision was reinforced by other decisions about more lenient speech rules that apply to the government when it acts as an employer.

The change that Scalia's death a month after arguments would bring to the Friedrichs case was one of the most certain effects of his death.

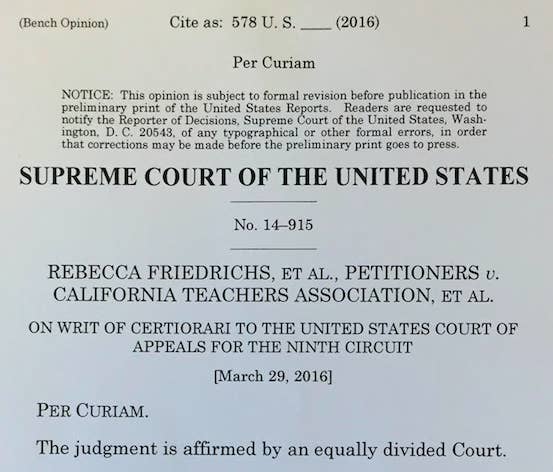

The court, in its unsigned, one-sentence opinion on Tuesday made that clear: "The judgment is affirmed by an equally divided court."