1. Zingers!

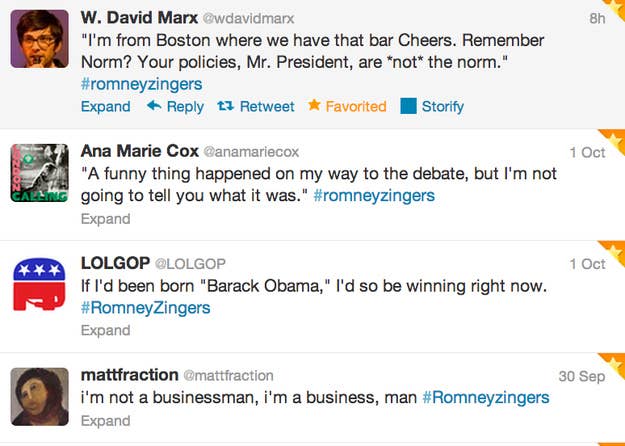

Since The New York Times reported that Mitt Romney has been practicing “a series of zingers” to use on Obama, Twitter has mocked the term and the strategy, but in fact those sharp-edged lines are the traditional way to “win” a debate and its aftermath.

The perfect, tweetable soundbite that undercuts the core of your opponent’s argument or points out hypocrisy or a character flaw usually ends up as the defining line — if not the deciding line — of the debate. At a line or two in length, they’re easy to put in print or replay on TV, providing an instantaneous free media boost to a candidate. They’re instant classics, set to make the quadrennial listing of best debate lines.

Zingers also reinforce the media — and thus the public’s — focus on these debates as gladiatorial bloodsport. They’re the equivalent of a swift jab to the gut that leaves the opponent momentarily speechless.

Ronald Reagan’s “There you go again” may be the highlight of the presidential forum, but the crème de la crème of zingers was delivered by Sen. Lloyd Bentsen against Dan Quayle in the 1988 VP debate.

“Senator, I served with Jack Kennedy, I knew Jack Kennedy, Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. Senator, you're no Jack Kennedy.”

Not all debates have them, but if delivered right, a zinger could end the debate with brutal efficiency.

2. Ignore the Press

Tonight’s old-fashioned presidential debate will be watched on old-fashioned television by many millions of Americans. Unlike many other campaign events — including most primary debates — viewers’ immediate experience could well trump insiders’ perceptions. And most Americans don’t see politics as sport — they’re looking to pick a president.

That means projecting warmth, authority, and stature — but probably not spending the evening hurling insults. Indeed, this is exactly the sort of performance media reporters dread — rehearsed, focus-group tested answers for the camera, feigned respect for the opponent, and a charm offensive that flies well over the media’s heads.

“A candidate aiming to win the ‘viewers’ debate wants to be seen as likeable,” former Clinton and Obama aide Blake Zeff wrote recently.

It’s very difficult, however, as Zeff noted, to both pander to the media and to ignore it, so good luck with that.

3. Get Under the Other Guy's Skin

Both President Obama and Romney have demonstrated relatively thin skins, as well as a shared tendency to get flustered when challenged — with differing, but equally disastrous consequences. The winner will be the candidate who best manages to exploit this tendency in his opponent.

When Obama is interrupted or attacked in a way he deems unfair, he often exudes condescension with a smirk, a disapproving headshake, and a scolding tone. It’s a weakness he demonstrated occasionally in the 2008 debates, but one to which he’s particularly susceptible now that he’s the incumbent. (Presidents don’t often get interrupted.) The reaction is damaging because it highlights all the worst traits assigned to Obama’s public persona — arrogance, aloofness, and a certain holier-than-thou elitism.

When Romney gets interrupted, on the other hand, he is prone to peevishness — obnoxiously reciting the rules, insisting on being allowed to finish his thought, and even appealing to the moderator. It’s a problem his aides have openly admitted to, and Sen. Rob Portman, playing Obama in their debate prep sessions, has reportedly made a point of personally attacking the Republican so that he can prepare himself for the offensive.

The key for each candidate will be to provoke one of these unappealing responses in his opponent without looking like a bully.

4. Spin!

The “spin room” — where aides to both candidates gamely recite their interpretation of the debate to a mob of reporters — used to be a crucial part of shaping media coverage. Twitter’s centralized conversation, rapid-response emails, and instant, televised focus groups have largely superseded it in expressing and forming the reactions of the television producers and writers who tell the debate’s story to Americans who didn’t see it.

The post-debate summits with staff and consultants, however, offer campaigns a last-ditch chance to soften or at least blunt negative narratives. The news cycle moves so fast now that the spin room is where you find a counter-intuitive take to instant conventional wisdom, and a response to whatever critique appears to be sticking.