Ever since its breakout growth became the story of the year, capped with a billion-dollar acquisition by Facebook, everyone is talking about Instagram. The Next Instagram, that is. Naturally, that means video. Like photos, but they move! To the casual observer, building the next big social network around video might appear to be a no-brainer.

As it so happens, Sean Parker, one of the driving forces behind the social network, has chosen to throw his weight behind the most recent addition to the mix: Airtime, also known as "Chatroulette without the dicks." Its launch was perhaps the most-hyped startup event since Color flushed the better part of $41M down the toilet.

Less than a week later, Airtime is far from being the Next Big Thing. The coverage I've seen thus far has mainly focused on how the user base is disproportionately male and kind of seedy (no dicks, eh?), the glitch-filled launch event, or how exactly the penis-detection algorithm works.

Why "Instagram for Video" Makes Absolutely no Sense

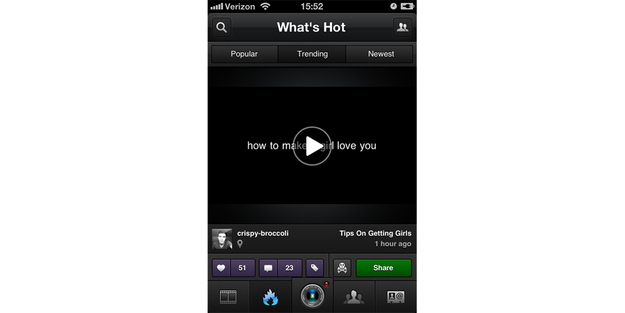

It doesn't feel like a stretch to say that we're in a video bubble. In fact, judging by the number of apps that are being billed as the "Instagram of Video" by the tech press — SocialCam and Viddy, Vlix, Boxee, and plenty of others abound — it feels pretty certain we are. But as these upstarts have discovered, video is a fundamentally different medium from photography, and so far no one has been able to replicate Instagram's success. Which raises the question: is a video-based social network really something we need?

I'm not so sure.

Which is quicker: shooting a photo of your cat doing something cute, or filming the same thing? Social networks live and die by user-generated content, and anything that introduces friction to the sharing process poisons the wells. It's just not quick, even in the age of streaming and widespread 3G and LTE networks, to record and upload a high-definition video to the Internet.

Of course, this also applies to the actual consumption of said video once it's been put online. With the exception of accidental videos and outtakes (think Failblog), most videos take more than a few seconds to watch. It's a far cry from a service like Instagram, where a user can quickly scroll through a feed and "like" photos to her heart's content.

There may be something of a happy medium in GIFs. Though nearly as labor intensive to produce as a short video clip, which limits their production, GIFs are inherently just as consumable as photos, as a quick scroll through Cinemagram, which has picked up over a million users in little more than a month, or Tumblr would show.

Flattery Will Get You Everywhere, and Vice Versa

But there's another, more important problem with video.

Social networks are driven by one simple, elemental motivation: our desire to present ourselves to others as we wish to be seen. This manifested itself early on, from the carefully curated profile photos on Friendster to the millions of aesthetic sins committed on the highly customizable Myspace, and continues to this day. Now, with "curation" quickly becoming shorthand for "the act of collecting random stuff on the Internet," Pinterest and Tumblr have become the dumping grounds for an embarrassment of inspirational quotes, photos of pretty girls with vintage bicycles, and macro shots of ornate dishes:

That person on Pinterest will never create those twee mini-cakes with the flawless icing and the tiny, ornate birds made of drizzled chocolate, and they don’t even actually want to, and you, in turn, wouldn’t even actually want to eat them, because fondant is nearly inedible. Those pins are about putting those isolated examples of orderly perfection in relation to ourselves like costumes. (Elan Morgan, We Can Become Known)

Have you ever seen yourself on video? You look terrible. Not to other people: to them, you just look like yourself. But there's something weirdly disassociative about watching oneself on camera. You notice how poor your posture is. You hear your own voice without the extra frequencies from sound being conducted through the bones of your skull. You think, "Is this what I really look and sound like?"

Videos taken from webcams and smartphone cameras are even worse. The camera usually ends up shooting from below, which is about the ugliest possible angle, so much so that the "FaceTime Face-Lift" is a real surgical procedure that you can have done for around $10,000.

With photos, you can pick and choose which moments to share. With video, it's all or nothing. You can't just edit out the moments where you don't look your best. And there are no ego shots.

The self-esteem deficit widens when you contrast your videos with your photos on Instagram. Those beautiful retro filters and square frames don't just make you look better, they mask the flaws in your composition and make you look like you know more than just how to press a shutter release. In comparison, most amateur video looks dull, shaky, and decidedly un-creative.

Where Airtime Went Wrong

In Airtime's case, it's even more uncomfortable because the video is bidirectional, and in real time. It's one thing to meet a stranger while out at night when you've (presumably) showered and put on your best face. It's another to meet them while sitting in front of a webcam. Could you imagine being at a party and having to watch yourself in the third person for the entire night?

Whereas Chatroulette was a complete free-for-all, connecting you at random with strangers around the world, and Google Hangouts deliver a confusing mesh of broadcasting and group chat, Airtime is supposed to be more like a cocktail party among friends — albeit one with an extremely enthusiastic host. But cocktail parties are usually best with a small, carefully chosen group of people. The massive pool of friends-of-friends and people who share your interests on Facebook ends up feeling less like an intimate gathering and more like a huge, impersonal networking event. Much like Highlight, another failed attempt to engineer serendipity, Airtime suffered from serious relevancy issues.

Some of this might be solved by refinements to what felt like a very bare-bones matching system. A disproportionate number of the people I met on Airtime all had one friend in common with me: a person who (surprise!) works in social media and thus has literally thousands upon thousands of Facebook friends. Others had little more than a few generic interests in common; the fact that you like Barack Obama and TED talks tells me as much about our chances for friendship as a shared interest in pizza. Airtime might be more compelling if it showed me people who share esoteric interests with me, or with whom I have more than just one or two shared connections.

But I wonder if improvements to the user experience would be enough to convince me to integrate the service into my life in any meaningful way. Besides a couple of very nice startup founders trying to raise a seed round through Airtime (bubble!), I didn't meet anyone interesting who I wouldn't have met eventually through shared connections in real life. And as those same founders aptly noted, we were all mainly interested in the service at launch due to the small cadre of early adopters that signed up during the first 24 hours. After all, when else would you have the chance to get nexted by none other than Mark Zuckerberg?

Perhaps we should stop chasing after the next Instagram and start asking ourselves what problems really need solving. If anyone needs ideas, I'm still waiting for my jetpack.

Ben Jackson is an iOS developer and writer living in Brooklyn, NY. He worked on news reader apps for the New York Times, and currently works on apps for Longform.