UIYA, Nepal — The week before my wedding, it became clear we didn’t have enough fuel to last the three-day ceremony. It was early December, in the middle of Nepal’s bone-chilling winter, and the state-run gas stations were rationing fuel, distributing it only to ministers, senior officials, and diplomats. I spoke to the man who was arranging the floral decorations, and he said he knew a man who knew a man who had a truck who could hook me up with “any amount of fuel you need,” but that I would have to dig deep into my pockets. Like many Nepalis, I had little choice but to buy it on the black market.

A few days later, a man brought me two dirty jerricans filled with diesel. I paid him $500 in cash, more than three times the market price.

“This is still cheaper for you than in America, right?” he said, with a smile.

On April 25 last year, thousands of villages, parts of the capital, Kathmandu, and a number of major towns around it were swallowed up by a devastating 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck Nepal. It was the worst earthquake to strike the country in almost a century, killing 8,891 people and leaving nearly a million people homeless. Monuments like the 19th-century Dharahara, the tallest building in the country, and a number of temples and palaces collapsed. The earthquake triggered an avalanche on Everest that blew through the base camp and killed 21 people, making it the deadliest day in the summit’s history. Villages in Langtang Valley, which sits in the lap of the Himalayas, ceased to exist.

For decades Nepalis had feared that their country would be struck by “the big one,” and to many, this was it. Before the earthquake, Nepal was already one of the poorest countries in the world, where half the population of 28 million earned less than $2 a day. In the time it took for the earthquake to shake the country, a million more Nepalis were plunged into poverty. In September, as the country was struggling to recover, it was hit by a man-made crisis, when a political row over Nepal’s constitution led neighboring India to impose a blockade, preventing even essential supplies from getting into the country. The lack of fuel grounded helicopters and trucks, erasing all hope of getting relief packages to the remote villages before winter came.

In the months preceding the wedding, I sent out reminders to friends, while keeping an anxious eye on news coming out of Nepal. I had invited scores of friends from abroad, and my father had invited hundreds more back home. My friends in America, having seen the devastation caused by the earthquake, and the impact of the blockade, began to wonder if it was a good idea for me to be getting married at all, and whether they should come. “Is it even safe? Are you thinking about canceling?” one wrote to me.

“I heard there is no food — how are you going to have a wedding in the middle of all this?” another friend wrote in an email.

For as long as I have known, Nepal had been this way: chaotic, dysfunctional, and, as many international publications like to say, “teetering on the brink.” But no matter what was happening in the country, life went on. I told my friends, “Don’t worry, this is normal in Nepal.” That was probably less reassuring than I meant it to be.

I flew to Nepal at the end of November for the wedding. Seven months after the earthquake, piles of rubble still lay untouched and almost nothing had been rebuilt — if anything, the future looked even bleaker. The evening I arrived, as I walked to my hotel in Kathmandu, I saw students clamber onto the roofs of buses and vans as they made their way home — the fuel shortage had brought many local services to a halt. In the morning, I picked up a few local newspapers, reading about earthquake victims in northern districts who were shivering under their tents in the freezing cold.

It felt odd to be celebrating my wedding amid all this tragedy. With a little free time before the big day, I texted my fiancé, Samikshya, and asked if she would be OK if I traveled to the south of the country to do some reporting. “Are you serious?” she wrote back. “You’re not going anywhere,” my mother said.

The following morning, I arrived in my hometown of Pokhara, a 25-minute flight from Kathmandu. Later that day, my grandmother came from Rupse, a village about a seven-hour drive west of Pokhara — she had rented a pickup truck for her journey, and filled the back with firewood that would last us through the wedding and beyond.

Trying to organize a wedding during a blockade was inevitably chaotic — in Nepal, the ceremony is a multiday affair with rituals that include the worship of hundreds of gods even before the big day itself. But my parents seemed unfazed by it all. My mother, who is a devout follower of Lord Shiva, told me, “Everything is going to go beautifully. Don’t worry.”

On the morning of the wedding, I was woken earlier than usual by the roosters in my neighbor’s backyard. My friend had arranged for me to ride a white horse to the venue, so I called its owner and asked him to give it a bath. My father helped me put on a traditional hat sewn to match my wedding outfit, pinched my cheeks just like he did when I was little, and said, “Now my son looks like a groom.” I had never seen him that happy. The lousy December morning suddenly felt like spring. The wedding, as my mother had said, did go off beautifully, and the following week, I returned to London with my wife. The blockade, in its fourth month, continued.

I returned to Nepal earlier this year to see what, if anything, had changed, nearly one year on from the quake. On a cold February morning, I set out for Uiya, a cluster of 10 villages and hamlets nestled in the craggy mountains of northwestern Nepal, spanning across the Budhi Gandaki River in the district of Gorkha. Sitting nearly 3,100 meters above sea level, it is one of the most isolated regions of the country and was devastated by last year’s earthquake. It is in places like this that Nepal’s challenging geography, sloppy politics, and the government’s lackluster efforts at reconstruction have, if anything, made matters worse.

Getting to Uiya from Kathmandu was a mission, first in a rickety old Land Cruiser, and then on foot, navigating winding roads and narrow mountain pathways. My driver, Raj Kumar, a talkative, middle-aged man, told me he had driven this route for years and that I had nothing to worry about, which did little to calm my nerves. At times the unpaved roads sent the jeep flying, twice forcing Raj to stop to tighten screws that had worked themselves loose. Sometimes the turns were so sharp, I could do little more than watch as the side of the jeep threatened to tip over the edge of the cliff.

When we eventually arrived in the small town of Soti Khola, the road suddenly ended at the banks of the Budhi Gandaki River. To get to Uiya, we had to hike up barely marked trails that were all but wiped out by the earthquake. To this day, aftershocks — of which there have been 445 of magnitude 4 or higher — continue to rattle through the country, causing more than 5,000 landslides since April.

The night before we started walking up from Soti Khola, around and across nearly half a dozen mountains, a rock came tumbling down and hit a girl on her chest, a woman who ran a small shop along the route told me when I stopped for some water. Some parts of the trail are so narrow that when donkeys carrying sacks of grain or gas cylinders pass from the opposite direction, your only option is to hug the sides of the mountain. At one point we came to a hanging bridge that had worked loose after the earthquake, and the only way across was to grip tightly on the wires and edge your way over, hoping they wouldn’t snap. As I crept my way over, I silently chanted a mantra my father had told me many years ago.

I eventually made it to Antar Besi, one of the tiny hamlets in Uiya, where I met a retired farmer in his early seventies named Ganja Bahadur Gurung. For months after the earthquake he had been left homeless, sleeping in his goat pen at night, subsisting on what little scraps of food he could find. The nearest delivery point for food aid was in the village of Laprak, half a day’s walk away, and Ganja Bahadur told me he was too old to manage it, so his wife, Pilwani, would set out at 1 a.m., torchlight in hand. While other villagers would rest along the way, Pilwani turned round immediately each time, returning with the sacks of rice by 6 p.m. to make sure she could cook for him.

“During the monsoon, I could hardly sleep without getting wet,” Ganja Bahadur said, as he showed me his dilapidated home. “I am trying to patch the walls that collapsed, so right now I sleep in a one-room shack I’ve made from plywood.”

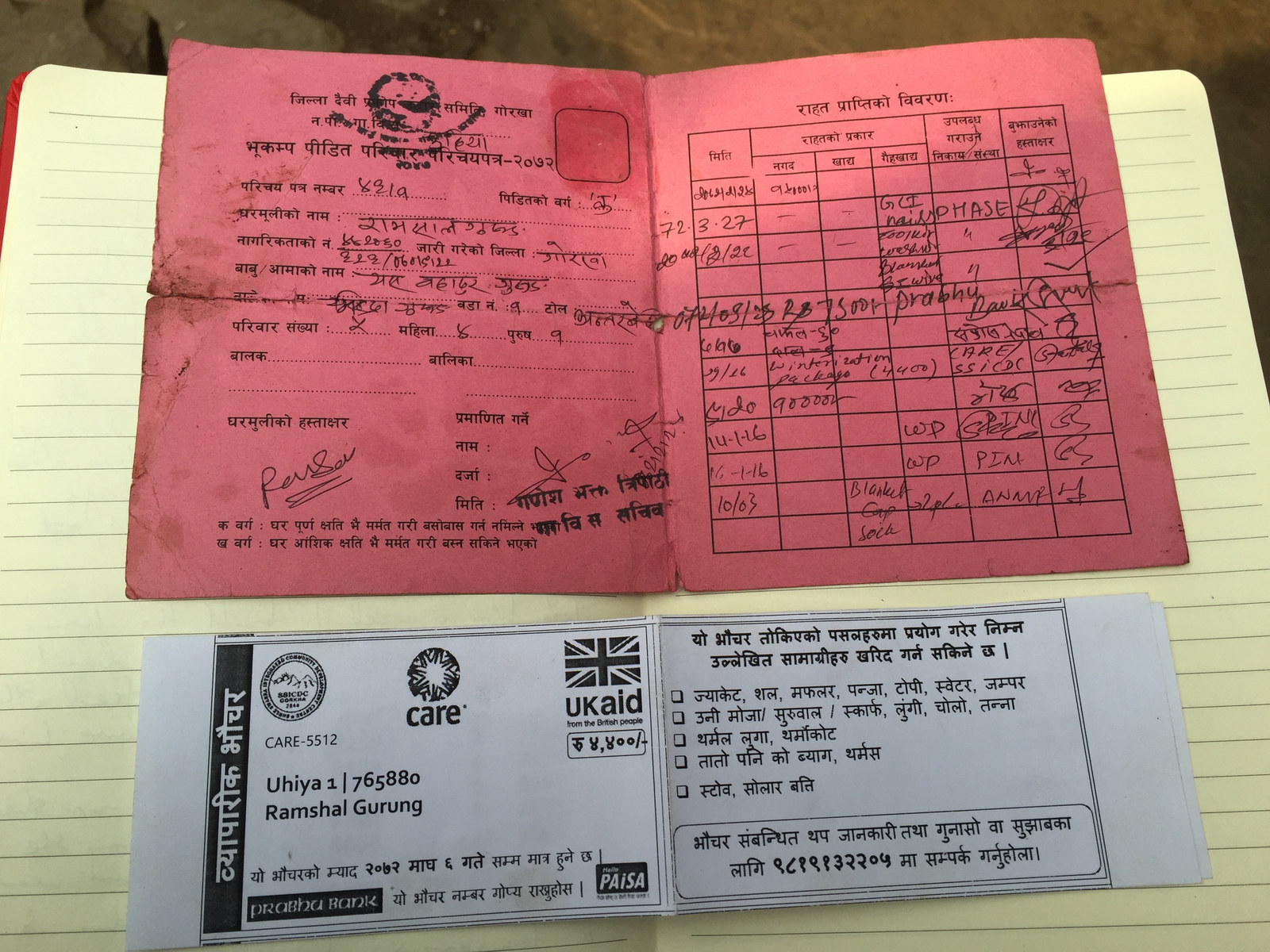

In the wake of the quake, the government issued everyone affected Earthquake Victim Family Identity Cards, which would record the aid it had given to the victims. The government had promised them supplies for the winter: 200,000 rupees (around $2,000) to rebuild their homes, and a reconstruction loan with little interest.

For villagers across Nepal these cards — known locally as rato card — were a lifeline. In Antar Besi, I met Ramshal Gurung, a young man in his thirties who had spent some time working in India; he protected his card inside two layers of plastic and behind one of the wooden beams above his bed. “They look at our cards and determine how much aid we have gotten and if we qualified for more aid. If we lose it, we may not get anything,” he told me. But the pink cards given to the villagers in Uiya showed they had received only 25,000 rupees (around $250) in two separate installments, barely enough to help build a temporary shelter and buy a few warm clothes and blankets for the winter.

I met the man responsible for distributing aid to these villages at a tea shop in Gorkha Bazaar, the district capital of Gorkha. Ganesh Bhakta Tripathi, a middle-aged man in a tight leather jacket and cargo shorts, worked as the Village Development Committee (VDC) secretary for Uiya. Sipping a heavily sweetened tea, he said the problem wasn’t that people had no money, but that they didn’t have anything to spend it on. Tripathi told me that the trails to the nearest market were so severely damaged that even if villagers could make it there, no goods would have arrived at the store for several months anyway.

Everything that comes into these villages is carried either by a drove of donkeys or on the backs of the young men who were born and grew up in the mountains. After the earthquake, the trails that connect one village to another were destroyed, and locals were forced to carve new, perilous pathways up and down the mountainsides and along rocky river banks. When the monsoon came in June, those banks were washed away. For many months, even the donkeys couldn’t pass.

As a result, the government used helicopters from the army and private companies to transport aid; thousands of tons of rice, lentils, oil, salt, blankets, and foam mattresses reached villages in far-flung corners of the country. But the aid agencies and the military landed helicopters only in certain villages — meaning the residents of the surrounding smaller villages were forced to trek, often for days, to collect their share. If they didn’t or couldn’t, they missed out on their share of supplies.

To make matters worse, most of the private helicopters hired for relief missions were originally designed for sightseeing and trekking tours and could carry relatively little. The cost of flying these helicopters was exorbitant and only a few international organizations could afford them. Documents released by the prime minister’s office show 4,236 helicopter flights were made after the earthquake for relief and rescue work, and the government says it paid $1.25 million to private helicopter companies. The World Food Program allocated more than $16 million of the aid budget for helicopter flights alone.

Given the scale of the tragedy facing Nepal, the amount of money successfully raised and allocated is negligible. Government records show that $830 million was raised through individual and foreign donations and via NGOs — and that almost all of it has been spent, although the paper trail is essentially nonexistent. Around $11 million from the Prime Minister’s Disaster Relief Fund was disbursed to Gorkha District, but there is no strategic accounting system and no way of knowing who got what. Although some food aid and money did make it to hard-to-reach places like Uiya, in many villages across the country, there are few signs of progress or hope.

At an international donor conference in Kathmandu in June 2015, the international community pledged $4.1 billion in aid. As things stand, not a single cent has arrived in the country. It’s hard not to feel that the worst catastrophe in Nepal’s living memory has now been entirely forgotten.

Even before the earthquake, Gorkha had been reduced to a forgotten city.

Once the center of power of the Shah dynasty that ruled Nepal until the monarchy was dissolved eight years ago, the city fell into quiet isolation after Kathmandu became the capital in 1769. For centuries, it acted as a way station for those visiting the nearby Hindu temple to Manakamana, a goddess believed to grant wishes to those who make the pilgrimage to her shrine. These days, pilgrims take the shorter journey by cable car, avoiding Gorkha altogether. The palace to the Shah kings is crumbling, occasionally visited by students on school trips. In recent years, villages in northern Gorkha, home to the scenic Manaslu Circuit, have become a route for foreign trekkers. But few Nepalis know this area, and even fewer have been to villages like Uiya, where locals, just like their forefathers four centuries ago, continue to herd goats and farm.

Life for the people of Uiya has always been hard. Although this is farming country, there was little to eat, even before the earthquake. Those who had saved some money might be able to afford rice and beans. The rest were forced to survive on a fistful of soybeans for lunch, and for dinner, a thin porridge of millet with steamed nettle leaves, which grew abundantly on the mountainsides. The nearest schools were either an hour’s walk up a steep hill to another village, or an hour downhill, across a hanging bridge. But not every villager could afford to send their children to school. For some, the 400 rupees you have to pay for a uniform, books, and stationery is too steep a price.

There was at least one thing everyone had in common: a home. They were often simple affairs, but they offered shelter against the cold.

The earthquake destroyed all that, swallowing up house after house, ripping goat sheds from the ground, and burying the grain that villagers had worked so hard to preserve for the year ahead.

After the quake, the government said it would give 200,000 rupees in three installments to each family to rebuild a new home. The one caveat: They would have to follow the government’s design, and the nearest place to find a blueprint was the District Disaster Relief Committee (DDRC) offices in the region’s main city, which for some villagers in northern Gorkha is at least a few days away, first on foot and then by bus.

But the designs produced by the government as “model homes” are controversial in and of themselves. Some local officials say these homes cannot be built in their villages because the topography simply won’t allow it. “It is easy for senior officers and ministers in Kathmandu to sit in Kathmandu and say ‘do this’ and ‘do that’ but they have no idea how bad things are in the villages,” said Tripathi, the VDC secretary for Uiya. “They don’t know how different one village is from another geographically. They have never been here.”

To make matters worse, local government officials said they also found that thousands of Nepalis had posed as victims to receive the 200,000 rupees in reconstruction grants. As a result, nobody — including real victims like Ramshal, the man from Antar Besi — has received any cash from the government to rebuild homes. It wasn’t until last week that the government finally released 50,000 rupees as the first installment of the grant, but to only 641 victims. Hundreds of thousands of victims have given up on the government and have decided to build on their own.

Ramshal Gurung and his wife, Mangani, used whatever materials they could find to build their new home.

With no hope of aid from the government, Ramshal gathered together a few corrugated sheets and wooden beams that had survived the earthquake and started putting together a new home. He finally finished it last December — a tiny room with two beds and a few blankets distributed by international aid groups, and an even smaller sitting area with a bench. A narrow space adjacent to the house serves as a kitchen, where his wife, Mangani Gurung, cooked on firewood. During the day, he sits in front of his home, where he runs a smaller shop selling a desultory few items: packets of filterless cigarettes, a carton of instant noodles, crates of eggs, iodized salt packets, three cans of Red Bull, two bottles of Carlsberg beer, and a jar of candy.

When I visited in February, Ramshal walked me to the back of the house, where he had built a small shed for goats. “They’re good for manure,” he said, and pointed at the onion and cilantro and cabbage plants his wife had grown. “If we grow these, we won’t have to buy food.”

That night, he asked his daughters to huddle around in the bed and made them do their homework under a dim light that runs on solar charge. Mangani made lentils and rice, the last remaining batch from the government ration they received many months ago. There were no hotels or lodges nearby, so after dinner, Ramshal helped me put up a camping tent on the farm across from his hut and offered me one of his blankets. Jackals howled all night, making sleep almost impossible. “I forgot to tell you all about them,” he told me the next morning, a sly grin on his face.

Having seen the distressing conditions under which Nepalis were living in villages like Uiya, I returned to Kathmandu to try to find out how much money the government had raised for earthquake relief and where it had gone. I went to the century-old government complex known as Singha Durbar, or Lion’s Palace, to meet Mahesh Prasad Dahal, a senior official who oversees the Prime Minister’s Disaster Relief Fund. Sitting in his office, he opened a string-tied paper file, spread it out on his desk, and read from it. “Everything we have received, we have spent,” he told me. According to him, the fund received nearly $230 million, of which approximately $150 million came from the government’s own coffers and the rest from donations from individuals and organizations around the world. Almost all of the $230 million has been disbursed to various government entities — and spent, according to one of the spreadsheets he handed to me. An additional $570 million was raised by various donor countries, local and international NGOs within the first eight months of the earthquake.

The chaotic mismanagement of the funds is enough to make your head spin. Government officials I spoke to at the finance and home ministries said they did not keep a record of how and where outside organizations are spending because they did not have access to their data. The prime minister’s office said it only kept records of how much money it received in the disaster relief fund, and what portion of it was handed over to the ministries. The ministries kept a record of how much money it had handed to the district offices. But neither the prime minister’s office, the ministries, nor the district offices kept track of how that money was being spent or how much money international NGOs were bringing in and spending in the districts.

“The Social Welfare Council might have it. Go ask there,” said one senior secretary inside the prime minister’s office. But despite half a dozen attempts to see the documents, the council ignored my requests. Each time, the person in charge was either on leave or had gone for lunch.

Baikuntha Aryal, a mild-mannered official who worked as a joint secretary at the Ministry of Finance, told me the government wanted to put all the foreign donations through one central fund, but it was unsuccessful. As a result, it had no idea how much money was coming in and how much was being spent. “It looks like the government of Nepal received all the money and officials are eating it here, but that is not the case,” he said, denying allegations that funds donated for the earthquake have been misappropriated.

In the aftermath of the earthquake, one official became the face of the government’s efforts to distribute aid in Gorkha, the hardest-hit area of Nepal. Uddhav Timilsina, a short man in his fifties who was known for his no-bullshit approach and acid tongue, was the chief district officer in Gorkha, in charge of managing aid distribution for hundreds of villages like Uiya.

I had spoken to Timilsina over the phone many times before we finally met in February at the Bakery Cafe, a popular restaurant in Kathmandu. As we sat down, he ordered a glass of hot lemon tea and proudly told me about all the good work he had done in Gorkha.

Timilsina, who has a tendency for the grand gesture, told me that within days of the earthquake he had put a sack with 140,000 rupees and the village secretary on a helicopter and sent it up into the mountains. “Within 15 days of the earthquake, I sent money to each and every affected house in the district,” he told me.

But that was hard to credit, given the evidence I had seen with my own eyes. The pink cards I had been shown in the villages in Uiya revealed that the first money didn’t arrive for 40 days. Some families said they never received a cent from the government — their cards were stamped, but the aid and cash came from People in Need, a Czech humanitarian organization, not the Nepali government.

Timilsina told me he had set up an office that oversaw all of the aid, money, and relief materials, to make the process smoother and more efficient. He claimed this allowed his team to keep track of the organizations and the aid they were bringing into his district. “The central government responded. It sent money, and then thought its work was over,” he told me. “But I was the one who actually managed the response. I was the one who didn’t get any sleep and any rest.”

“He was decisive and whatever he did in Gorkha helped things move fast,” said Suedip Joshi, the program manager for People in Need, which has been working in a few districts devastated by the earthquake.

Things did indeed move fast in Gorkha. So fast that, soon after the quake, nobody was able to keep track of how much money was coming in, who was operating in which villages, and what relief supplies were going out to the victims.

News reports in the country’s biggest daily, Kantipur, said members of major political parties misused aid materials that were supposed to go to earthquake victims. Nearly 1,800 sleeping mats that were intended for villages like Uiya were divided among political cadres, according to the paper. Furthermore, members of the ruling communist parties — United Marxist Leninist and Maoist — and the opposition Nepali Congress took huge amounts of rice, lentils, salt, and oil to feed party volunteers.

“The aid supplies were distributed based on influence,” I was told by a volunteer who had knowledge of the political party members’ activities in Gorkha, and who agreed to provide details only on condition of anonymity. “A lot of the political cadres who came to work were fed with supplies that came for the villagers who were hit hardest by the earthquake.”

In one case, the local politicians from the United Marxist Leninist Communist Party used their influence to fly helicopters with aid to the village of Chhoprak, which wasn’t that badly affected by the earthquake. Government officials were then given goats and chickens as gifts, which were slaughtered for a feast inside the DDRC office compound, to which female dancers from a neighboring district were invited, according to the volunteer.

When I pressed Timilsina about the allegations of corruption, he denied a feast had taken place but conceded there had been a low-key “get-together,” during which police officers and soldiers drank and ate because “they were tired.”

Timilsina admitted that helicopters had flown with aid to Chhoprak twice, but said that as soon as he found out, he immediately ordered the halt of further flights there. “Yes, Chhoprak had some political leaders and they may have influenced one of our officers,” he said. “The houses there only had small cracks so the village didn’t meet our requirement for response.”

Then there is the story of the generators. Much of northern Gorkha had gone dark after the earthquake; in Uiya, villagers were left without power for many months after fracturing crevasses brought down the hydropower transformer that supplied electricity to three villages. In response, the Chinese government donated nine generators, but none of them made it to Uiya. Instead, they were used by Timilsina’s office, the local army camp, the police headquarters, and the armed police headquarters in Gorkha. When I asked Timilsina if this was true, he looked at me quizzically. “Yes, the generators came as donations. And I did give it to the police and the army and the DDRC office — they were working all night and they needed it,” he replied, unapologetically, as if it were entirely logical that the people who most needed the generators did not receive them. Gesturing wildly, he said Nepal needed officials like him to push forward reconstruction efforts. I left, bewildered at his claims that everything had gone smoothly under his watch.

Mired in political infighting, Nepal’s government and its political parties wasted the better part of a year fighting among themselves over a new constitution. Whatever little time was left, they spent trying to undo the blockade imposed by India in September. The reasons for the blockade are hotly contested in Nepal and India, but the effect was devastating. For the next five months, all essential supplies — fuel, cooking gas, medicines, food — coming into the country ground to a halt. In December, the U.N. World Food Program said it had delivered only a third of the food supplies it had allocated for distribution by the end of the year. Nepal’s leaders, entangled in their own political battles inside and across the border, did little to help. “Until the crisis ends, rebuilding will remain in limbo,” the spokesperson for the government’s Home Ministry told the BBC News.

In between all of this, the government changed, electing a new prime minister, who then appointed six deputy prime ministers in an effort to keep his coalition partners happy. All of this stalled — and politicized — the process to choose and appoint someone who would head the National Reconstruction Authority, which was formed to oversee the post-earthquake reconstruction.

In December, the government finally announced that the CEO of this national body would be Sushil Gyawali, a cheery civil engineer who had been heading the Town Development Fund. But senior officials, including some those who had worked in the government for decades and were vying for his job, questioned Gyawali’s appointment, and his lack of experience.

It wasn’t so much that Gyawali was inexperienced — he had just never been in the political or public spotlight before. I met him in his office in Kathmandu, where, unlike most senior government officials who wear the national dress known as Daura Suruwal, he wore a Western-style coat and tie, and he was working on a Saturday afternoon, a public holiday. “What do you think? Tell me,” he said, when I asked him if he thought he was up to the task. Whatever the answer, three months after he took office, more than half the officials asked to report to the reconstruction office haven’t showed up. There were empty cubicles inside the office, while hundreds of thousands of Nepalis wait for the government to help fix their homes, bridges, trails, roads, and highways.

“We are going to build, but we’re going to need time to ensure safer construction,” said Gyawali, who was quick to point out that the country’s geography makes it difficult to transport proper construction materials to the hundreds of villages that were damaged by the earthquake. There is tremendous pressure on his office to finish rebuilding homes before the rainy season starts, but when I spoke to Gyawali in February, he said that such deadlines were impractical.

“If you look at Pakistan, if you look at Gujarat, or just look at Japan — it took them three to four years with their level of technology and resources to finish any significant level of reconstruction work,” he said. “In Nepal, it is too ambitious to expect things to happen on time, and that too, before the rainy season.”

After two straight days of trekking high up in the mountains of Uiya in early February, I limped my way into the village of Khorla Besi. Exhausted, distressed by what I had seen, and disturbed by the government’s incompetent response, I paused on the stone steps that lead into the village. There, I was approached by a short, smiling man in a thin trekking jacket and a faded baseball cap bearing the name Cristiano Ronaldo. Sarki Gurung insisted that I rest on his porch and drink some buffalo milk. He brought me a steel cup with lukewarm milk filled to the brim and told me his life story. Last year, before the earthquake, he had nearly slaughtered the buffalo as a sacrifice to the gods, but changed his mind when he noticed how much milk the buffalo was providing. In the wreckage of the earthquake, it is now his only source of income — he sells milk to the villagers for 100 rupees a liter.

When the homes of people like Sarki were destroyed, the government said it would allow bona fide victims to take a reconstruction loan at a 1% interest rate. Toward the end of last year, Sarki went to the local government office to find out how to apply for it, but he was told the initiative hadn’t been implemented yet and he’d have to come back. Frustrated, he borrowed 150,000 rupees from a few people he knew, at 48% interest.

“We don’t know if the government is coming to help us. We don’t get any news here. There is no electricity, we don’t have a TV, and the radio doesn’t work because the mountains block the transmission signals,” he told me.

Having been forced to live under tarpaulins and tree branches during the monsoon last year, Sarki has finally managed to build himself a new home, using corrugated iron sheets, old wood, and tree branches — all tied haphazardly with coiled wires and ropes. The floor of the house is made out of a thin layer of rectangular wooden slabs, supported entirely on tree branches dug into the ground.

But to Sarki, it is everything. “It’s better than shivering inside a tent, right?”

Neither Sarki nor many of the villagers I met in Uiya are angry, despite everything they have endured. Even the potentially ruinous debt they have taken on doesn’t seem to get them down. What Sarki said really worries him — what keeps him awake at night — is fear. Fear that another earthquake will come and destroy the tiny ramshackle new home he has made for himself.

Pradeep Bashyal contributed reporting for this story.

UPDATE

This post has been updated to reflect the fact that the World Food Programme allocated $16 million for helicopter flights, not $100 million, as originally written, based on inaccurate figures supplied by Nepali officials.