The first thing I do every morning is take my phone, wedged carefully beneath my pillow, and check my sleep stats. They’re tracked, in a weirdly calming graph of blue-blacks, within an app called Sleep Cycle, where I’ve used them to feel very, very good about the sleep habits of a thirtysomething, childless journalist. Sometimes I take screenshots of my stats, hovering so self-righteously over eight hours a night, and send them to friends; earlier this fall, I Instagrammed a particularly impressive 10 hours, the result of a solid dose of strep throat medication.

For most of the last three years, I've lived by the gospel of my sleep quality percentage. So what if I had a dream so vivid that I woke up in tears and felt like I’d slept not at all? My sleep quality said 88%, so I was expecting a B+ day.

But I also harbor a shameful secret: I cheat. I simply opt not to track the nights I stay out like my college-freshman self. They mess with my stats, which is to say, they mess with the way I like to believe and present how I live my life. Therefore, I pretend they don’t exist.

I had been tracking my sleep for three years when I discovered that even if I hadn’t periodically cheated, everything I thought about “quality” was, in fact, suspect. As multiple engineers, scientists, and designers who have devoted themselves to creating devices that track sleep with precision told me, Sleep Cycle — and, for that matter, any app or device that uses motion to judge sleep quality — is incredibly imprecise. As one researcher put it, “actionless sleep and good sleep are not the same thing,” a finding echoed in numerous scientific studies.

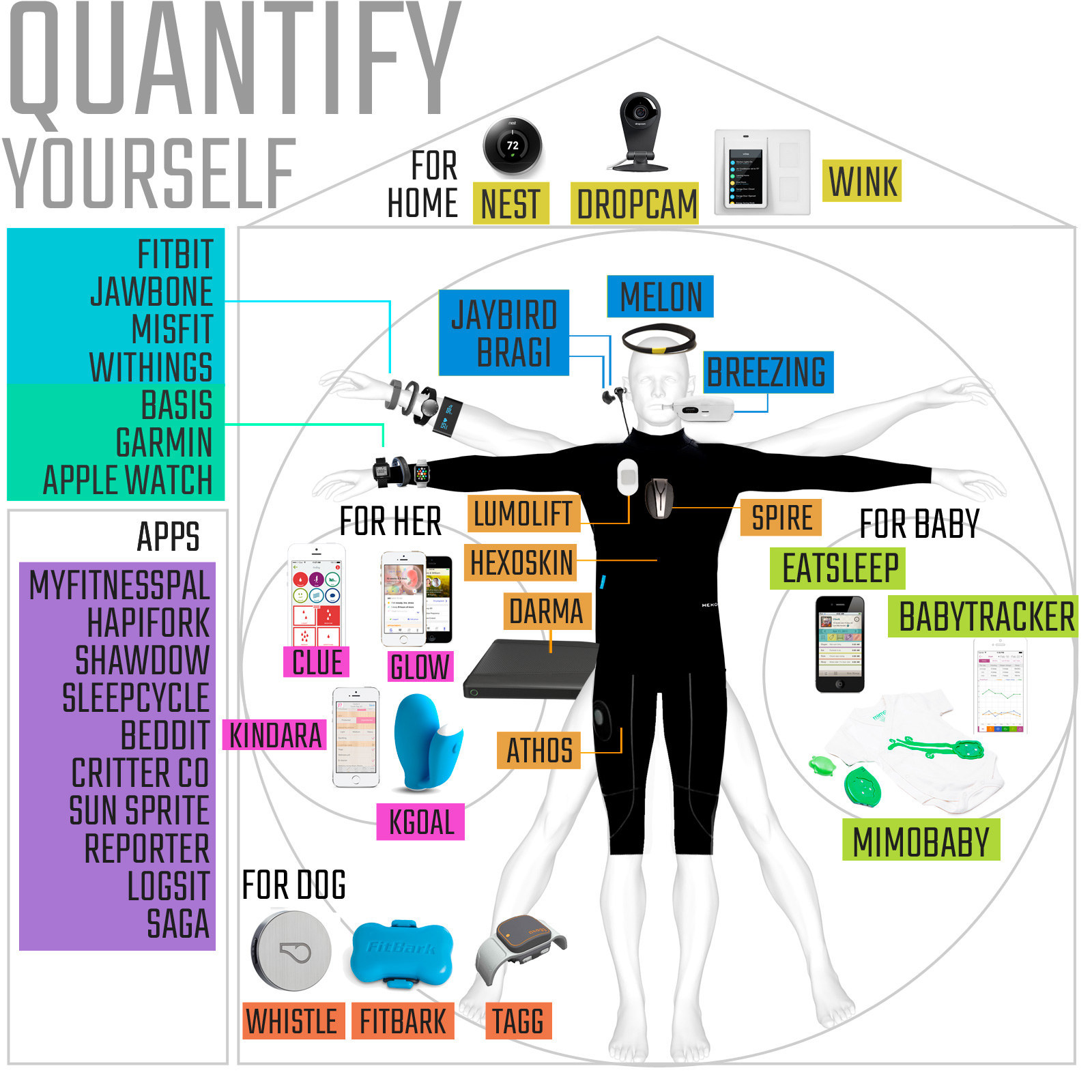

Weirdly, I didn’t feel betrayed so much as curious, because they aren't the only ones in this emerging space: By 2018, there will be 60 million fitness trackers in use worldwide. In, outside, and around the body and our homes, the devices just keep coming — in part because the funding does as well: As of September 2014, $1.4 billion in venture capital funding has been directed toward the wearable and biosensing market; by 2018, wearable sales are expected to push $30.2 billion. Fitbit and Jawbone have attracted a significant percentage of that capital ($66 million and $470 million, respectively).

For most of the last 25 years, the internet concerned itself with taking existing information and organizing it in a way that made it instantly accessible; these new devices are capturing data that used to be inaccessible and turning it into something knowable. Yet talking with nearly two dozen companies, it seems clear that the molded plastic of the fitness tracker and the dubious findings of the sleep app are merely the rudimentary beginnings of an all-encompassing cultural groundswell.

The next generation of devices — led by the Apple Watch, which aims to put health trackers on 15 million wrists — will focus on providing actionable insights on everything from posture to sun exposure, from blood oxygenation to infant respiration. Another host of devices communicate with our homes, our pets, our cars; others will track our elderly parents and our wandering children. Still more will track focus in the workplace, compliance to prescriptions from physical therapists, exposure to sunlight, and our ability to conceive. The breadth of devices and their utility is so vast that it's proven difficult to name the trend: Quantified Self, Internet of Things, Everything-Tracking — nothing quite fits. The thesis that unites them, however, is clear: The future will be quantified.

Fears of what can be done with this data are not unfounded. In 2013, a San Francisco man was convicted of vehicular manslaughter using Strava data concerning his speed on his bike, and an upcoming civil case will be the first to use Fitbit data; in that case, Fitbit is being used to protect the individual — a personal trainer, injured on the job, who claims that her baseline activity levels remain below average for someone of her age and occupation.

It’s not difficult to imagine a future in which similar data sets are wielded by employers, the government, or law enforcement. Instead of liberating the self through data, these devices could only further restrain and contain it. As Walter De Brouwer, co-founder of the health tracker Scanadu, explained to me, “The great thing about being made of data is that data can change.” But for whom — or what — are such changes valuable?

To explore these questions, I wanted to take my own tracking to the next semi-obsessive level. Thus: a step tracker, which uses an accelerometer to estimate your steps and, in more recent models, your sleep. I researched the major players in their various levels of size, sophistication, and color. I decided I’m not glam enough for the Tory Burch Fitbit or Misfit Bloom, instead settling on a black Jawbone UP24, which looks as if a child wrapped a fat pipe cleaner with silver tips around your wrist.

I calibrated it to my Jawbone iPhone app; I added my height and weight; I set it to vibrate every time I’d been sitting, sedentary and stupefied, in front of my computer for more than 30 minutes; I learned how to press the moon button to let it know that I’d gone to sleep. I pleasured in looking at my stats every time I walked the 30 steps across the office. I reveled in blowing away the 10,000 recommended step count. It was the first blush of gadget love.

Which was the feeling that accompanied me as I signed up for the quarterly “meetup” of the Bay Area chapter of Quantified Self, the most innovative and exhaustive self-trackers in the world. I arrived nervous and somewhat embarrassed of my rudimentary tracker as I stepped off the BART, staring at the words “Berkeley Skydeck” and “start-up accelerator” on the meetup invitation. I felt like I was about to meet some amplified version of my people.

Turns out, "skydeck" was San Francisco-speak for office space atop an otherwise unremarkable high-rise. The vibe was that of a church service or even an AA meeting. In place of cheap cookies and weak coffee, there was craft IPA, assorted finger sandwiches, and a swarm of QS “greeters” who encouraged the 100-plus attendees to write our names on name tags. The crowd looked very early-adopter, which is to say almost entirely white, mostly male, with a strong representation in the 30 to 60 age range — classic Gadget Dads. There were also grad students and hippie moms, confident tech bros name-dropping venture capital firms, and a handful of confused wanderers, like the guy who came up to me and whispered, “My friend dragged me here — what the hell is going on.”

In the last decade, the tracking inclination has simultaneously coalesced and expanded through the organization of Quantified Self, a group defined by its interest in self-tracking and subsequent discoveries, with membership in the thousands that now spans the globe. Quantified Self first entered the popular awareness in 2010, when co-founder Gary Wolf, then a contributing editor for Wired, outlined the movement and its fascinations for the New York Times Magazine. Since then, QS has become a tech curiosity, alternately heralded as real-life cyborgs and condemned as “datasexuals” whose embrace of self-surveillance will usher in a dystopian future.

Like most write-ups of subcultures, the lived experience of Quantified Selfers resides somewhere much less extreme than how they’ve been previously profiled. Between Chris Dancy, who uses 300 to 700 tracking systems at all times, and Nicholas Felton, whose Annual Reports have become fetish objects, you’ll find people who are tracking aspects of their lives in innovative and significantly less flashy ways, usually centered on health, hobbies, and genuine curiosity about the way they navigate the world.

Back in the Accelerator, the carpet was a bit stained, and the windows — which, in daylight, would’ve given a spectacular view of the bay — needed cleaning. But the enthusiasm was palpable. Beers in hand, attendees chatted with the half dozen hosts of science-fair-like setups that lined the wall: A fresh-faced twentysomething showed off a bare-bones system to track his productivity (and asked me if I had any leads on a job); two feet away, a team of blue-polo-shirted car insurance salesmen enthusiastically tried to convince me, despite my lack of a car, to track my driving habits.

Dressed in a natty pair of jeans and pink dress shirt, QS founder Gary Wolf roamed the room like a pastor, shaking hands, remembering everyone’s name. When he convened the group, he extended his arms, telling us, “I’m so happy for us to be together again.” Before the night’s three planned presentations, Wolf offered a preamble filled with credos (“not big data or small data but our data”), visuals (a pyramid reorienting the way that “prevailing wisdom” has been, and will be, sorted), and a heartfelt message to those who had never been to a QS meetup to participate: as trackers, as presenters, as volunteers.

The presentations focused on tracking online dating behavior and an attempt to solve “output” (read: poop) problems, oscillating between the entertaining and the triumphant. In this, they were representative of the type of presentation that takes place at more than 100 similar groups around the world. Participants may lose weight, or figure out what’s causing their eczema, or make a plan to maximize their working hours, but it’s really the intimate revelations and self-discovery that keeps people coming to these meetings, talking with others about their projects, and figuring out new ways to track.

As I listened to Greg Schwartz, a classically handsome QSer in a Superman shirt, talk about his efforts to “quantify” his dating life, I was struck less by the weirdness of these presentations and more by the value of the findings: The guy with output problems did, indeed, solve them (nuts and flaxseed were to blame); another trying to sort his memories figured a way, using an elaborate flashcard system, of pegging calendar days to distinct mental snapshots of his life. Schwartz figured out he should definitely stop putting “firedancing” in his first flirtatious dating message. Even as the technology of self-tracking becomes more and more sophisticated, the ways that Quantified Self were tracking had much more to do with pen, paper, and Excel spreadsheets than pricey gadgets.

Still, tracking behaviors that, in Wolf’s words, just seven years ago were “the strangest thing you could think of to do” have gone mainstream. What was once limited to a handful of tech-savvy obsessives is now the provenance of middle-class, middle-America moms, who have increasingly embraced apps like MyFitnessPal and trackers like Fitbit.

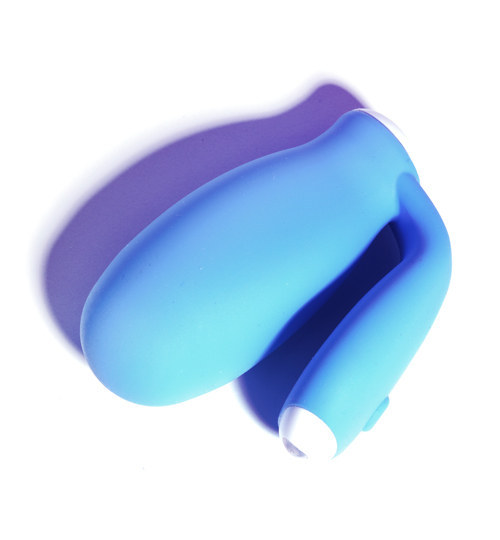

The highest concentration of self-tracking companies are, unsurprisingly, in the Bay Area, with ambitious startups ranging from modest two-person side projects to bustling staffs with over 100 employees. At Basis, which was acquired last spring by Intel in a preemptive attempt to compete with the Apple Watch, they were about to release the Basis Peak, touted as “the ultimate fitness and sleep tracker,” and the mood was one of hip confidence, the office framed in leather couches and road bikes. By contrast, the offices of Minna — the small operation responsible for kGoal, a device that helps track pelvic floor health (the muscles that help you do kegels) — were housed in a co-working space in San Francisco's Dogpatch neighborhood, its co-founder apologizing profusely for the lack of fancy digs. Lumo Body Tech, which occupies a drab, indistinct office building in downtown Palo Alto, helps monitor posture.

Then there’s Whistle, which makes round, silver devices that monitor your dog’s activity, linking with users’ fitness trackers to provide activity data and, soon, GPS tracking. Whistle's offices were resplendent with very well-behaved dogs — all tracked, naturally, by Whistles — and appropriately located near several pet rescue operations off of San Francisco's Treat Avenue. Whistle co-founder Ben Jacobs was boyish, talkative, eager, and followed everywhere by his dachshund-terrier mix, Duke, who shared many of the same characteristics. Jacobs is bullish on the future of the rapidly expanding market for devices that track what he explained as “the four areas that are valuable, but can’t speak for themselves: our homes, cars, infants, and pets.”

The most prominent company in this first arena is Nest Labs, which sells “smart” thermostats, smoke alarms, and cameras to monitor the home, all of which can be controlled via mobile and will soon communicate with wearables to adjust to fluctuating body temperatures. For the car, Progressive Insurance has been promoting the use of Snapshot, which monitors mileage, time of travel, and how hard you brake, since 2011, luring users with the promise of lower premiums. Nest-owned Dropcam is also vying for a slice of the lucrative pet-monitoring market, which targets the same owners who buy high-end pet food and pet insurance. (Nest, like all of the companies I interviewed for this piece, protects specific sales data.)

And then there are the babies. The most holistic baby-tracking devices come from MimoBaby, whose “Smart Nursery” currently includes a respiration-sensing “baby kimono” that not only protects against SIDS, but combines data about the baby’s feeding, naps, and sleep patterns to determine whether a waking baby needs to be fed or can be settled back to sleep; a smart mobile that zeros in on the sounds and images that put your baby to sleep; and, coming soon, a bottle warmer that will communicate with the kimono to start warming when the baby begins to wake. The ultimate endpoint is an integrated future in which all of these devices work seamlessly with one another — when the baby wakes, for example, your activity monitor decides which parent is less tired and thus should be alerted.

As I sat in the high-ceilinged, tall-windowed, exposed-brick offices of Rock Health, a venture capital firm specializing in funding health care technology, a distinct vision of the future of tracking devices came into focus.

“We’re basically looking for three things,” said Malay Gandhi, managing director of Rock Health. “Things that are actually functional, focusing on an aspect of human physiology that people actually care about and can act on. Ideally the device is also clinically useful and reliable, meaning the data is actually actionable and valid and can be held to a clinical standard. The last area is convenience: If people don’t want to wear the thing, you have a big problem with getting any data from the sensor.”

Jawbone and Fitbit dominate their corner of the market — a combined 87% of the fitness tracker market in 2013 — but from an investment standpoint, there’s a marked hesitancy toward them, manifest most poignantly in New York Times technology critic Nick Bilton’s April 2014 piece, in which he questioned the “snake oil” quotient of popular wearables (and step counters in particular) and their “slick marketing but suspect results.” (Fitbit told me that third-party tests have confirmed that its trackers are the "most consistently accurate activity trackers on the market"; Jawbone says the UP is intended to function as "an overall lifestyle tracker" with a goal to "really understand your baseline, and discover things you might not have known, so you can start to make decisions.") Fitbits and Jawbones sell well, but “decay levels,” to use Gandhi’s words, are high, and customer satisfaction, even gleaned from Amazon review pages, is relatively low: The Fitbit Flex and Jawbone UP24 are currently rated 3.5 out of 5 stars on Amazon.

The reason these devices don’t routinely score raves is because they lack a clear promise that they can in turn fulfill. “When you look at the marketing for these step counters, it’s very broad and aspirational,” Gandhi explained. “If you go and read the five-star reviews of Fitbit, they’re largely about losing weight, but if you read their public marketing, Fitbit still has this aspiration of being more of a health and wellness brand than weight loss.”

In contrast, a device like the Lumo Lift promises to give you better posture through the use of a device, magnetically affixed to your lapel or shirt, that buzzes every time you slouch. Gandhi explained that “the five-star review on the Lumo Lift says ‘works as advertised.’ You will never find a review for Jawbone or Fitbit that says ‘works as advertised’ because no one knows what they’re advertising.”

With complaints of faulty and uncomfortable hardware and questionable accuracy, many reviews point to a generalized ambivalence toward the device and its utility. Which is exactly how I felt about my own tracking device, six weeks in: Within days, I was ignoring the buzz that was supposed to prompt me to get up from my sedentary state. Within two weeks, I was regularly forgetting to set it to “sleep” mode. My steps leveled out at around 12,000–15,000 a day, but once I knew that number, what value was it to me? Eric Topol, an expert on the future of quantified health care, told me step counting is a “pseudometric,” and he’s not wrong: Finding myself annoyed by step counting made me feel like a pseudoperson.

Still, both Fitbit and Jawbone have hundreds of thousands of users who preach their gospel. But trackers have still penetrated only 3% of the marketplace, and as analysts have predicted, their growth will spike before being overtaken altogether by smartwatches, with the Apple Watch poised to lead the way. By contrast, the next generation of devices will promise ways to think about our bodies and lives in fundamentally more sophisticated, profound, and actionable ways.

To find a company doing this sort of work, I had to go to NASA. Or I at least had to go to the NASA Ames Research Park, where Scanadu occupies one of the buildings where NASA engineers once lived, worked, and stared up at the shuttles constructed across the way. Now the offices feel like a disarming mix of ‘60s industrial and repurposed cool, like hip sandstone bunkers in the beautiful Mountain View sun. At Scanadu, I was greeted by Walter and Sam De Brouwer, the husband and wife team from Belgium (him) and France (her) who are working to build an entire suite of devices that will replace the diagnostic and laboratory components of health care.

The De Brouwers were a charismatic team: Walter had the energy of a teenager, the hair of Einstein, and a habit of creating magnificent turns of phrase and elaborate, learned metaphors — the mad scientist manifest. Sam, by contrast, looked everyone straight in the eye, and spoke with the sort of focus and clarity that reminded me of a family physician. When they couldn’t remember the English word for something technical, they consulted each other in whispered French.

Sam held a sleek white Star Trek-ish tricorder called the Scanadu Scout to her temple, and showed me as the app on her phone received readings of blood pressure, temperature, blood oxygenation, and more, generating over 560,000 data points in just five seconds. As is, most people have their blood pressure, pulse, and weight recorded at a yearly check-up, if that. The addition of accurate daily data from the Scanadu would combine empirical data from the individual with observed trends within the population; the potential of that sort of combined data is seemingly limitless.

Walter trumpeted the “dashboard” ability of these devices, which will allow a family member to check in on their loved ones when traveling. Simply turn on the app, and you’ll see that your kid, partner, or elderly parent is in good health. It’s not “Big Brother,” he explained, so much as “Big Mother.”

The De Brouwers' vision matches the one co-opted by hundreds of companies today, most notably in its retreat from the rhetoric of surveillance, which remains redolent with shadowy, nefarious connotations. Users are instead told that they’re “monitoring” themselves, involved in “joyful discovery,” and “liberating their data.” In this way, those who would otherwise recoil at the thought transform into users who are not only willing to participate, but willing to pay for the privilege.

Companies employ interlocking strategies to simultaneously encourage use and distract from the implications. The first, and most obvious, is aesthetics. Self-tracking devices and apps shed the cold, alienating darkness of covert surveillance with warm, sunny colors and clean, “universal” design, reminiscent of an Apple product.

Take Lively, which designs tracking devices that allow “sandwich parents” to monitor aging parents as they stay in their homes (and out of assisted living). Lively is situated in San Francisco’s Presidio, a vast area of rolling green hills now designated a national park and rapidly filling with upstart companies. The offices, in a square, squat house that once served as a military barrack, are filled with light, people talking on the phone with customers, and scattered boxes of Livelys in various stages of packing and shipping.

While other companies aim for hip, active early adopters, Lively’s founders realized that the senior market was almost completely untapped, filled with companies that have prided themselves on their lack of innovation. As co-founder David Glickman told me, the beige plastic devices on cheap metallic chains that currently dominate the market “look like they were designed in the 1970s.”

“If you talk to an elder, they say, ‘I’m not gonna wear it,’” Glickman explained, “because it’s ugly and/or it’s the last signal to the world that they’re old and frail.” By contrast, Lively’s sensors, which house accelerators that, when placed on refrigerator doors, pillboxes, and elsewhere, alert the elder’s adult children of their activity, are white and pleasant to the eye; the Lively watch, which serves a dual function as pedometer and emergency alert, resembles the Apple Watch. As Glickman told me, even the name of the company is intended to change attitudes toward elder care: “This is more about living than it is about ‘I’ve fallen and I can’t get up.’"

Lively products look nothing like the dark, eye-in-the-sky 1984 aesthetic with which surveillance is popularly depicted — a dissociation that extends to its website, which, like the vast majority of the sites for tracking devices and apps, bears a similar aesthetic: The font is rounded, soothing; the sites send you on a seemingly infinite scroll through pictures of happy, fulfilled, healthy-looking users. Even the names of the products themselves attempt to convey some sort of basic humanity: Apart from Scanadu, which embraces its sci-fi otherness, names like “Olive,” “Jaybird,” “Nest,” “Plume,” “Wink,” “Melon,” and “Shadow” imitate Apple’s ability to make the inorganic — the bytes and chips and metal of the computer — into devices that feel like they integrate organically not only with the home, but the body.

It’s one thing to disassociate an object with surveillance. It’s another to get people to start using your product — and using it consistently. For their tracking, Lively had to convince a demographic that hasn’t necessarily resigned themselves to the data trade-off of using sites like Google and Facebook.

Glick explained how the company works with “choosers” to talk to their parents (“users”) about the utility of Lively; tips include having a grandchild do the asking, and emphasizing how it will replace nagging with meaningful conversations. The real clincher, however, is the “LivelyGram” — a packet of printed-out photos and notes, assembled by members of the elder’s network and delivered, via mail, twice a month.

LivelyGrams have been an astounding success, so much so that the vast majority of support calls aren’t about the actual device, but questions about when their next LivelyGram will arrive. However altruistic the aims of Lively may be, it’s also a vivid manifestation of how companies lure trackers, and their data, with promises of pleasing, usually affective benefits, which, at least in LivelyGram’s case, capitalize on elderly users’ loneliness and desire to connect with family as a means of incentivizing self-tracking.

Jawbone offers a study of the somewhat obvious (weather affects your tendency to exercise); MyFitnessPal maps the “Pumpkin Spice Plateau”; Fitbit tracked the cities in which users racked up the most Halloween steps (areas with suburban sprawl) and the most logged Halloween candy (Snickers). These posts employ soft, banal panaceas to make data donation seem fun and meaningful, while simultaneously distracting from the more unsettling ways a company might make use of collected data.

Period-tracking app Glow offers a variation on that concept in the form of Glow First, which, as Jennifer Tye, Glow’s head of marketing and partnerships, enthusiastically explained to me, is basically “crowdsourcing for babies.” Ten couples join the program; each pays $50 for 10 months as they attempt to become pregnant; at the end of those 10 months, the couples who failed to conceive split the “pot” of accumulated money to pay for fertility consultation and treatment.

Glow emphasizes that the program is “not for profit” and simply a means for families to help alleviate the costly burden for those who struggle to become pregnant. At the same time, all users must provide extensive daily logging information in order to participate; the program is “free” and “not for profit” only if you believe that extensive data sets are without monetary value.

In reality, user data is every tracking company’s most precious resource. They promise to provide the user a new way of thinking about their dog, their daily steps, their period, their focus, or their calorie consumption, but they’re also providing the company’s lifeblood — a means to make the product indispensable.

All of these strategies aim to keep users engaged, to further refine the hardware and software. The more active and consistent users, the more data, and the more they retain and attract active and consistent users, who generate even more data. And the more data, the more attractive the company becomes to potential investors and/or buyers. Comprehensive data sets catch the eye of Google and Apple, of course — both of which seem intent on building holistic data sets of consumers — but also big pharma and health insurance providers.

But the real issue — and why observers and investors like Rock Health don’t see Fitbits and Jawbones as the future — is that even more complicated than collecting this information is finding clear ways to make it meaningful.

What if you could advance science by doing nothing at all, save allowing data gleaned from your body — what some call “digital exhaust” — to be aggregated, analyzed, and used to advance modern medicine?

This is yet another way that self-tracking companies incentivize the voluntary “donation” of data — it’s not surveillance, after all, if you’re volunteering for it. In most cases, we even pay for the privilege of providing this information — not to the government, necessarily, but to companies with great power that may or may not be subject to government requests for that information.

This “sharing” is currently being facilitated through corporate wellness programs, in which companies, in conjunction with insurance companies, promise to lower premiums in exchange for data. At Fitbit, corporate wellness is a cornerstone of its business model; it offers programs for small, medium, and “large enterprise” companies with 1,000-plus employees, from BP to Boston College. Participating employees can compete against one another for “points,” reductions in premiums, gifts, and generalized feelings of superiority.

Fitbit promises employers that they’ll “create a culture of well-being,” “improve participant health status,” and “increase worker productivity,” and according to several former and current participants in such programs, they do fulfill at least some of these promises: Corporate competition can become cutthroat, with participants fighting to park the farthest away in the company parking lot.

Many, however, used the Fitbit only until the end of a promotion — or simply stopped using it after a few months. The reason, according to analysts, isn’t that these employees are lazy, or hate fun: It’s that the logic of compulsive tracking and competition employed by Fitbit simply doesn’t work for everyone. As Christine Lemke, co-founder of The Activity Exchange — a startup that facilitates communication between insurance companies, tracking devices, and patients — told me, “A single company buying 30,000 Fitbits is a stupid idea.” The mean drop-off rate for Fitbit usage is 271 days: Some people love it, others hate it — not because there’s something wrong with the Fitbit so much as no single device can be tailored to incentivize wellness in all populations.

Which was probably the overarching problem with my Jawbone: When the battery life became erratic around six weeks in, that was essentially license to take the device off. The novelty had worn off, and as someone who was already active, I wasn’t motivated to do anything new — instead of appreciating its ability to track my steps, I was annoyed at its imprecision in doing so, especially on runs (the same run never tracked the same twice) or while spinning or doing yoga (which it didn't track at all). I felt cheated, but really I just needed a device better tailored to my specific needs: a Garmin or Basis Watch partnered with apps like MapMyRun and Strava. It’s not that the Jawbone was a bad device so much as it was a bad device for me.

The promises for the future of self-tracking/employer partnerships, however, go far beyond a Jawbone-like fitness tracker and deep into the chronicling of worker productivity: when employees focus best, how they perform in the hour after lunch, how their heart rate jumps during meetings with certain supervisors. This type of data isn’t yet available — it’s contingent upon wide-scale corporate adoption of a device like Spire, which tracks respiration and focus — but representatives from several companies underlined the potential, when implemented through corporate wellness programs, to increase worker productivity. In theory, this wouldn’t be used to discipline employees but to do things like optimize the workplace or gauge the validity of worker's compensation claims.

For example, the ProGlove, a device that promises to "unlock a new level of control and business intelligence for production management," also means having proof of the exact muscles and means through which an employee injured themselves and whether a company is on the hook for treatment. Better "business intelligence," in other words, is actually just more precise and cost-efficient employee monitoring.

As every entity in this space is keen to emphasize, your data is private and, when aggregated by a company for macro-level insights, anonymous. But as scholars have demonstrated, the de-anonymization of data is far from impossible, and most users neglect the lifespan of data: It may be contextualized now, but it may also be decontexualized — and de-anonymized — in the future. A user might sign up for a service with one understanding of its privacy policy only to have it change without warning, as was the case with Moves, which quietly modified its privacy policy to allow for sharing of data with “affiliates” after being acquired by Facebook in April 2014.

When asked whether collaborations with insurance companies might create a new class system — divided between those whose bodies quantify well, and are thus insurable and employable, and those, such as the disabled and differently abled or just plain chronically ill, whose bodies don’t — the companies I interviewed emphasized that the Affordable Care Act would prevent such a scenario. But as this year’s midterm elections yield promises to repeal the central tenets of the ACA, those assurances seem naive, if not disingenuous.

Granted, there’s a legitimate argument that privacy concerns can actually hinder scientific progress, and it’s difficult to hide behind privacy fears when faced with the potential for massive advances in mobile health in the developing world, meaningful decreases in domestic health care costs, and irrefutable reductions in nationwide obesity rates.

Such advances sound great, but for many — especially anyone who’s in relatively good health — they’re fairly abstract. That’s how I felt, at least until Scanadu’s Sam De Brouwer showed me the latest project in their suite of mobile health devices: the Scanaflo, a urinalysis strip.

For the first time, I felt like I was catching a clear, practical glimpse of the future: The user urinates on the strip much like a pregnancy test; the strip then “lights up” 12 different reagents. Take a picture of the reagents with your phone — it works in any light — submit it, and receive a diagnostic in return. It detects pregnancy, of course, but it also detects the proteins present from a urinary tract infection, or UTI — currently responsible for a staggering 10 million doctor visits per year.

If you’ve suffered from a UTI, you understand just how exciting this development is. The pain of the UTI is swift, severe, and an instant wrecker of plans; untreated, it can lead to severe kidney infection and death. But even more importantly, once you’ve had one UTI, the symptoms are instantly recognizable. The Scanaflo has the potential to eliminate hundreds of thousands of doctor visits yearly and unquantifiable amounts of pain — but only if it can go from prototype to widespread practice. Still, it’s a tangible, immediate example of the sort of fundamental change of which these sorts of devices are capable.

Scanadu’s potential is all the more real given that, unlike most other tracking tools, they’ve committed themselves to obtaining FDA approval — a designation that competitor Vital Connect has already obtained. While other devices and apps meticulously track hundreds of inputs, they must all be careful to underline that while their algorithms can suggest a user consult a health care professional, without FDA approval, they simply cannot make any diagnostic claims.

Yet the De Brouwers — and idol-smashing doctors like Eric Topol — don’t see devices replacing our health care system so much as altering the current relationship between patients and doctors, in which the former suffer in relative ignorance, waiting for learned experts to interpret their symptoms, tests, and health history. Scanadu, along with devices like it, aims to redistribute that power differential: “2015 will be the Woodstock of mobile health,” De Brouwer explained to me, “and Eric Topol will burn his stethoscope on stage.”

Even if self-trackers fail to bring about the Woodstock of mobile health, they will certainly give the user a semblance of power vis-à-vis knowledge of their own bodies, labs, and diagnoses; the potential effects of the democratization of that information isn’t all that different from the spread of the printing press, at least in its capacity to wrest authority from a small swath of educated people and distribute it. This idea is unsettling — a vision of a small army of very anxious, hypochondriac mother-in-laws comes to mind. Yet the spread of any technology, especially ones like the printing press, the train, the telephone, even birth control, that threaten to fundamentally alter the established order of knowledge and society, will always incite a similar reaction.

But advances in health still don't get to the true appeal of these devices — something that Natasha Dow Schüll, a cultural anthropologist in MIT’s Program in Science, Technology, and Society, has been thinking about for the last several years. As Schüll told me in her MIT office, littered with discarded and unopened trackers, there are fundamental differences between QS, in which people “design their own algorithms and experiments and report on them to a group,” and “the aisles of Best Buy, where people are buying devices that already have set algorithmic parameter and defaults.”

Most users, in other words, want a frictionless experience that requires as little effort as possible. These passive users’ amenability to inviting devices into their lives — whether health-, home-, or fitness-based — isn’t about generating more data, or a desire to think more critically about their lives. “There’s all this rhetoric of empowerment and taking charge,” Shull said, “but what all of this actually indicates is a desire to not make decisions and choices about our own behavior.” We’re fatigued, in other words, with the sheer amount of decisions that structure the 21st-century life.

In their capacity to tell users what to do — or simply do it for them — these devices exploit thus our collective weariness with the decisions that structure a typical day: Can I have this cookie with lunch? Do I need to bring a tampon to work? Am I doing these squats correctly, what’s the best workout playlist, I feel off, what the hell is wrong with me? Just think how much time you could save if you weren’t thinking elliptically about whether or not you should shell out the $50 co-pay to go to Urgent Care.

In their own advertisements, these devices promise to save you from worry (about your aging parents, about your slouching back) so that you may live life free from technology. As Whistle founder Ben Jacobs told me, monitoring your dog is actually intended to take you away from your phone, generating a space for “quality (screen-less) time.” “Millennials are much more conscious about trying to create happiness,” he said, and “the devices that succeed will be the ones that make you happy.”

The future will be quantified, then, because these devices promise the latest iteration of what we’ve always sought: happiness. Which, at least in the 21st century, doubles as simplicity. A life in which your heartbeat and respiration and location dictate when your house turns off and on; a life in which the guesswork of eating and exercising and the mysteries of our bodies could be eliminated. That promise of ultimate, seamless simplicity — and the happiness that supposedly accompanies it — will be too much, even for the most suspicious and privacy-conscious among us, to resist.

That presumes, however, that happiness is rooted in transparency. That knowledge is a source of peace; that being able to see and send every heartbeat is the ultimate in intimacy. That a life made of data — a life that is readable and, as such, changeable — is life at its most optimized.

Obviously, there are benefits to this optimized, quantified self, not least of which is the ability to make significant medical advances and alter the lives of those suffering from chronic, and often mystifying, illness. But there’s something to be said for the allure and beauty of the mysteries not only of our confusing, previously unknowable bodies, but the intricacies of life. For the daily banalities of tuning the thermostat, or of knowing you had a good night’s sleep because you feel good, not because an app indicated as much. For the pleasure of running without knowing how fast or how long or how many calories but simply because your body could and did move, and that even without a digital trace, a GPS footprint, or way to leverage evidence thereof against friends and co-workers — it nonetheless felt something like being alive.

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for our Sunday features newsletter, and we’ll send you a curated list of great things to read every week!

The author would like to thank Harvard's Berkman Center technology scholars Whitney Erin Boesel and Sara M. Watson for their assistance with this piece.