The set of Good Girls Revolt is filled with the technology of a bygone era: looping sheets of telex, Rolodexes, typewriters, landlines. The characters who fill it wear a mix of ’60s conservative (oiled, well-parted hair for the men) and the burgeoning counterculture (so much fringe). In many ways, Good Girls Revolt picks up where Mad Men left off: The year is 1969, the setting Midtown Manhattan. And while both shows are, broadly speaking, fictional, Good Girls Revolt is “inspired” by the real events that took place at Newsweek over the course of a decade, when female employees successfully launched a complaint against the magazine for sexist workplace conditions and practices.

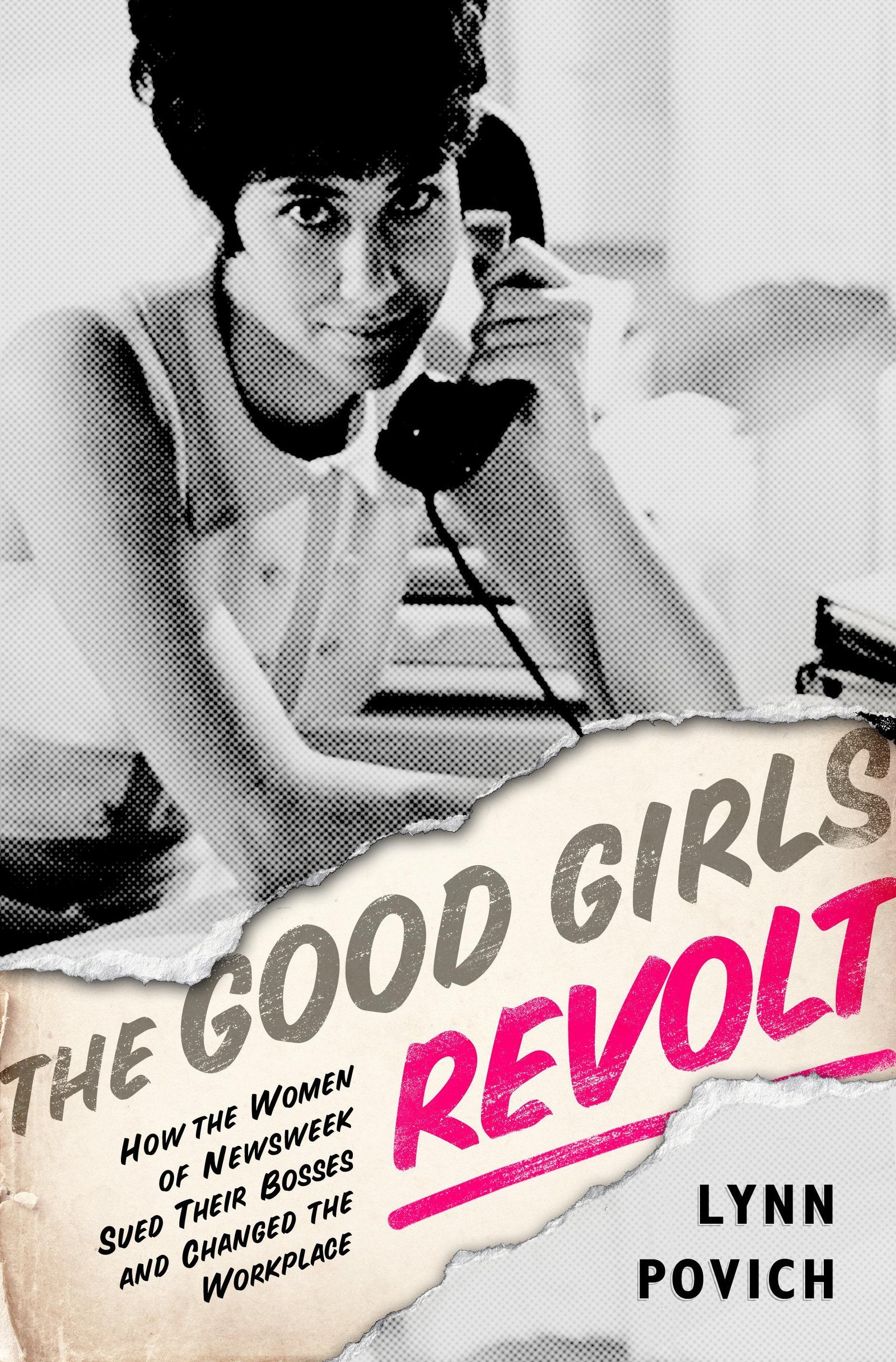

The Amazon series is based on a book of the same name, written by Lynn Povich, who participated in the two equal-opportunity complaints against Newsweek. For the television version, Newsweek has been transformed into News of the Week (to avoid legal issues) and several of the real-life characters have become composites, while other, more prominent figures remain intact — Grace Gummer, daughter of Meryl Streep, plays Nora Ephron, while Joy Bryant plays Eleanor Holmes Norton, the storied activist and ACLU lawyer who spearheaded the original Newsweek complaint.

The pilot, now streaming, only hints at the larger schism and political action to come; for now, it’s a snappy story of how a group of women began to grow dissatisfied with a system that refused to reward their work. Like nearly every news organization of the time, Newsweek divided the labor of journalism along gender lines. On one side, there were the researchers — women who dug deep into a story’s history and oftentimes did the bulk of the reporting, including interviewing sources. Researchers were paired with writers (all male, with a few exceptions) who would then transform that work into what you read on the page. The byline — and credit — was the writer’s alone, and women were not only discouraged, but often banned from moving up to the position of writer or editor.

The show opens at the Altamont Festival in 1969, where a riot breaks out among the thousands of members of the counterculture who’d flocked to see “Woodstock West.” The rest of the episode traces researchers Jane (Anna Camp) and Patti (Genevieve Angelson) as they try to figure out what really happened (the answer involves Hells Angels, a “plaster caster” named Juicy Lucy, and a back-up singer for Santana) while their older, old-school editors (Jim Belushi and Chris Diamantopoulos) push back.

But that’s just the plot around which the larger gender tensions swirl. The pilot — and the rest of the season, if picked up by Amazon among the slew of TV pilots it’s released on its Prime service — raises questions about which jobs should be considered appropriate for women, whether women can be taken seriously as sources, and whether writing by women, however good, would be published in the magazine.

Good Girls Revolt thus promises to follow the women of the newsroom as they gradually realize that their position is unfair — and figure out what to do about it. Some, like Jane, whose perfectly sculpted bouffant is a work of art, are more entrenched within the status quo; others, like Patti, are already radicalized and eager to piss men off. The pilot has some of the broad strokes and clunky exposition that plague nearly all first episodes of TV shows. And yet the retro analog feel of the 1969 journalism world is propulsive and addictive, leaving viewers wanting much, much more.

Showrunner Dana Calvo, a former journalist herself, is quick to note that the show isn’t some feminist manifesto. “If it feels at all issue-y, or preachy, we’re dead in the water,” she says during BuzzFeed News' tour of the Long Island set in August. “It’s gotta be a soap, with love triangles, lots of drinking, lots of fucking. The stakes are simple: Will someone get to be with the person they really love? That’s the show, set against the backdrop of Oh, by the way, these young women are accidental revolutionaries.”

Or, as Gummer explains it, “Women don’t want to watch a show that’s about, like, women in the workplace. I think it’s patronizing, in a way — people don’t talk about ‘male empowerment,’ or, like, ‘men in the workplace.’” The actor doesn’t even like the phrase “female empowerment.” “I like effective,” she says, readjusting her Ephron wig between takes.

The show certainly has romance — and the women are definitely working toward efficacy. Yet it’s also dramatizing one of the most important, and under-told, struggles in feminist history. With their comments, Calvo and Gummer might be trying to broaden the potential audience for a show filled with complicated and abrasive women, but the notion that no one wants to watch an explicitly feminist show underlines just how unresolved many of the problems facing the women of Newsweek remain.

Like, say, the enduring gender and pay gap in Hollywood. But that — that's something Calvo’s not shy about trying to change. “We wanted a female director. But the list we were given to consider — from the studio, from Amazon, from our agents, our managers — was so short," she says. "The thinking in Hollywood is, Oh, there’s only a handful of women directors. Well, sure, if you keep only giving the same women these jobs, then that’s true! But if you expand that pool a bit and give someone like Liza Johnson, who’s never done TV, but has done three films, a chance — well, she’s killing it.”

“There are so many qualified, amazing women working behind the scenes,” Calvo continues. “And they just don’t work as much as men. But our first assistant director is a woman, our second assistant director is a woman. Production designers are almost always men, but ours is a woman. ... That’s what I’m most proud of right now.”

The work of costume designer Laura Jean Shannon on display at a women's consciousness-raising group and in the newsroom.

Good Girls Revolt showrunner, the director, the executive producer, the writer of the source material — all women. Costume designer Laura Jean Shannon, best known for her work on Iron Man and Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, puts it this way: “I do superhero movies, which I love. I’m a geek. But this is a different atmosphere. After we filmed the feminist consciousness-raising meeting, every one of my female producers, plus the writer, director, everyone, sent me emails: ‘Every woman was so amazing; there were so many types of woman, you really nailed it!’ I have this really eclectic group of women working for and with me, and then having a female director and producer really recognizing the work that we do... It’s just great to really be living the byproduct of the story we’re telling. Because I wouldn’t be here doing this without it.”

Which isn’t to say the industry has reached actual equality. “I wouldn’t say we have equal pay,” Shannon says. “But we’re getting there. Of course, there’s different things that come when you’re having women run the show. Here, I never feel like, Well, they wouldn’t be treating me like this if I had a cock and balls, which I do feel like when men are running the show. But I do get a lot of scrutiny about the color of dresses I chose!” At this, Shannon, whose elementary-age son was playing nearby, laughed loudly.

Back on set, they’re filming a scene in which one of the young researchers has a torrid makeout session with her writing partner in the News of the World infirmary — a regular occurrence, according to Povich’s book. Povich herself is there on set, along with her husband, whom she met during her time at Newsweek, and executive producer Lynda Obst, who’s spent the last 30 years observing the gendered dynamics of Hollywood. She’s produced dozens of movies, including Sleepless in Seattle — written by Ephron. “Casting Nora was the hardest part of the whole process,” she whispers as the crew resets the take. “Originally, Grace wasn’t available.”

After the scene wraps, Jeannine Oppewall — a gloriously no-nonsense woman and one of the most celebrated production designers in the business, with four Oscar nominations to her name — explains the various details of the newsroom set. “Lynn was a friend of mine. Her first husband and my only husband were friends at film school, and that’s how I got to know her," she says. "And she ditched the husband and I ditched the husband and we stayed friends. When she got to be the first female editor at Newsweek, as a result of her and her officemates’ suit, I just thought, Wow, this is fantastic.”

Oppewall goes over every element of the amazingly period-realistic set, noting how the central challenge of the design was to enact a metaphor — the physical and symbolic divide between the men and women. “Down there you have the pit, which is a windowless purgatory,” she says. “And up here you have the bullpen, which is full of men with raging hormonal requirements. And then up the stairs, that’s the heaven of the gods who run the place.”

“The men can all watch the girls,” she continues, pointing to the pit’s physically lowered status. “And the girls have a much harder time looking up. Yet there are sight lines from all the way back in the pit to all the way upstairs. And the staircase, you see, it has a turn. You have to stop, pause: The journey from down there to up there is not straight.”

She talks about how some objects, like the ubiquitous gray desks, would’ve dated all the way to before World War II, while the furniture in the snazzy editors’ offices would’ve been filled with mid-century modern — a style Oppewall is uniquely well-versed in, having worked with Charles and Ray Eames, whose work is central to the mid-century aesthetic.

“I lived through all this stuff,” she says, referring back to the various fights of the feminist movement. “It took me a long time to get into the Art Directors Guild, because it was a boys club and they did not think women belonged. But I knew I wasn’t going to be any damn good at being some decorative wife. All of us women worked really hard, but each was in her own corner.”

She succeeded, then, through self-reliance — and on sets that aren’t Good Girls Revolt, she still has to. “Most of the really big movies I’ve done, they’ve all been run by men. I can turn around tomorrow and go work on some Clint Eastwood movie, and I guarantee you I will be the only hen in the rooster coop,” Oppewall says. “Most men are just more comfortable with their own. And then I get in there, and I cause different ways of thinking, and feeling, and I upset the cage.”

Like the rest of the female members of the crew, Oppewall knows the work the women of Newsweek started isn’t yet finished. "The feminist fight isn’t over at all," she says. "As soon as you take two steps forward, somebody wants to push you at least one back. And then you have to regroup and push forward again. ... It's all about reaching a critical mass where there are enough women that it just seems normal, and natural, and crazy that it wouldn’t be that way."

Good Girls Revolt may be about a bunch of accidental revolutionaries. Its politics may be embroidered with melodrama, and romance, and fixation on clothes. But, then again, so is life. And that doesn’t make the show, or the work of the women behind the scenes, any less feminist — or necessary.

As Oppewall says, “Sometimes I look at my nieces, who don’t quite yet see the amount of work it took for us to pull this off, and I’m like, ‘You better have a look at the past, because if you’re not vigilant, the past can always be your future.’ You gotta babysit it and talk about it and push it and make it seem like this is absolutely the way it should be.”