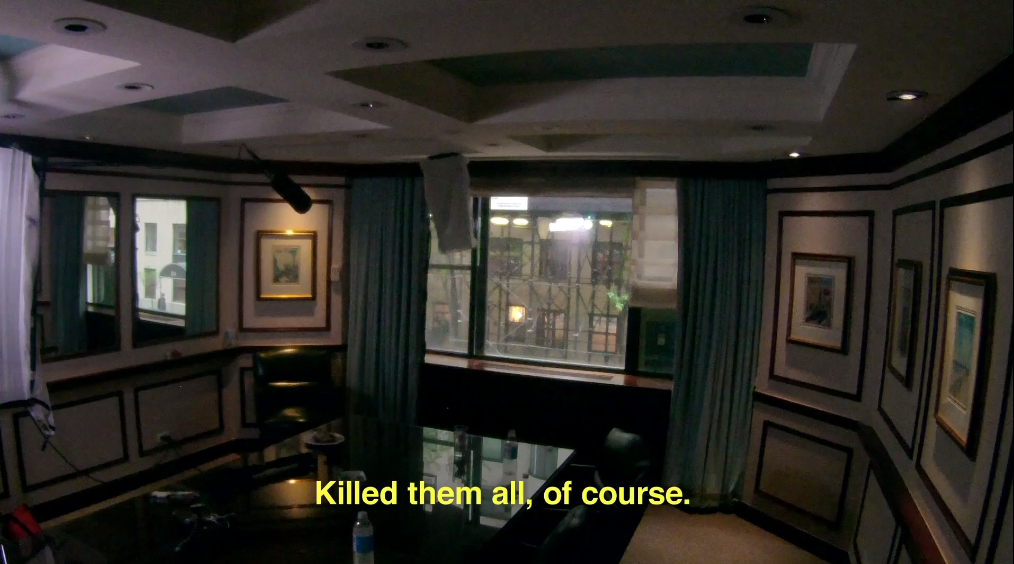

HBO's six-part The Jinx ended last night with a huge revelation: Robert Durst confessing into a hot mic while he's in the bathroom, "Killed them all, of course." (Read more about the series here.)

Even if you've spent the previous five episodes slowly being convinced of Durst's guilt in three murders — of his first wife, best friend, and neighbor — Durst's bathroom mumblings, which sound like a conversation between him and a private devil, are incredibly unsettling. They're also a perfect, and seemingly earned, payoff.

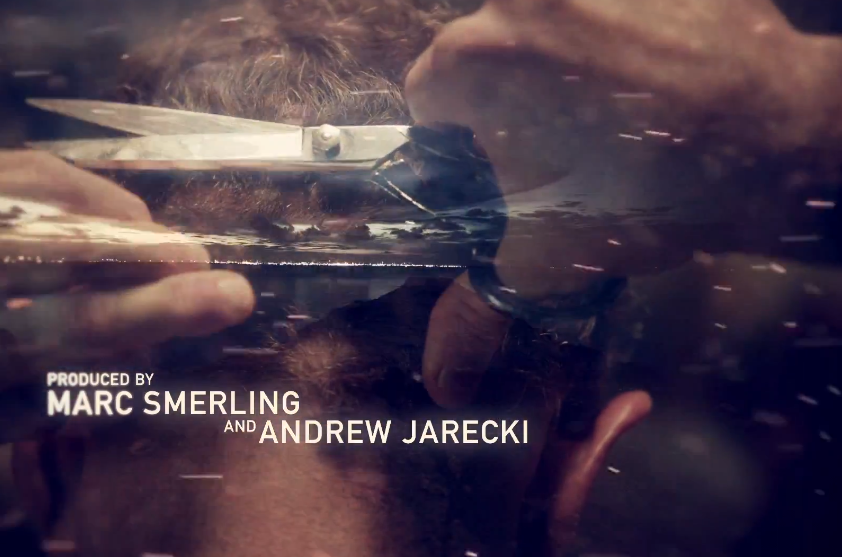

Yet that confession — and the entire sixth episode — wouldn't have nearly as much power if not for the deft filming and editing choices of filmmaker Andrew Jarecki and his team, including a timeline that seems to have been significantly manipulated at several points to create a more linear and compelling narrative.

The conclusion of The Jinx is the sort of neat ending we get from fiction films, not real life, the events of which seldom unfurl in an order conducive to compelling storytelling. It's clear that the team behind The Jinx manipulated the order of events around this second interview. It's possible and probable that other audio and visual portions have been manipulated as well.

Certainly, every story, no matter how "real," involves specific choices as to how that story will be told. It's easy to remember as much when it comes to narrative (fiction) cinema; it's harder when it comes to documentary (ostensibly nonfiction) movies. How exactly did The Jinx — an unquestionably compelling, entertaining, and addictive television show — narratively manipulate its viewers?

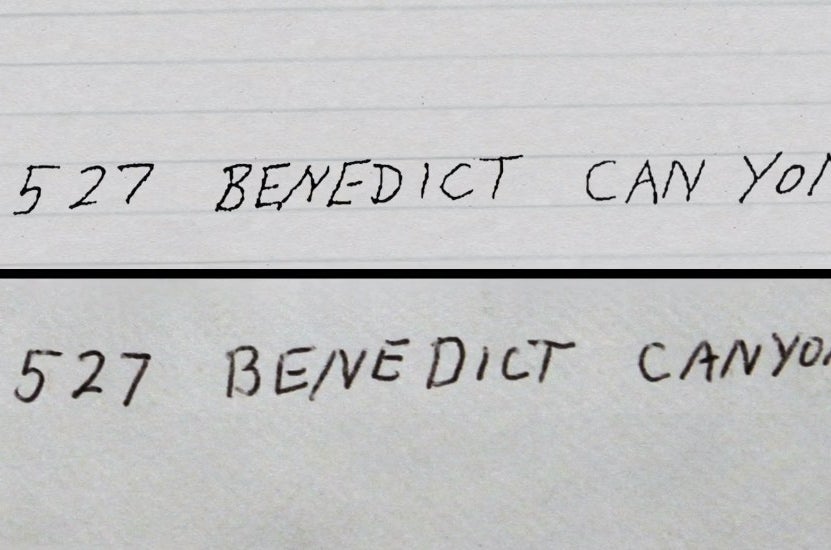

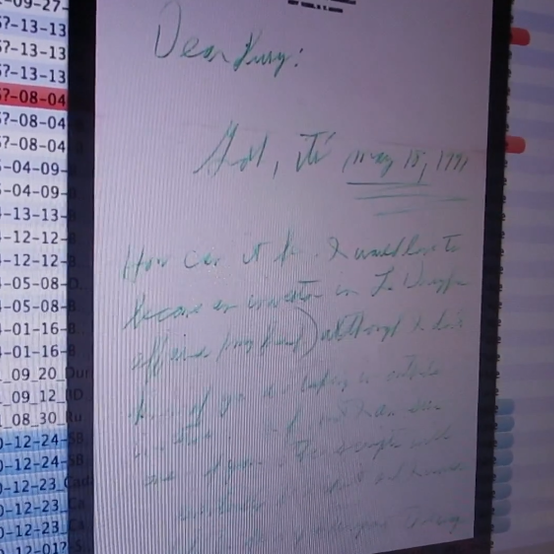

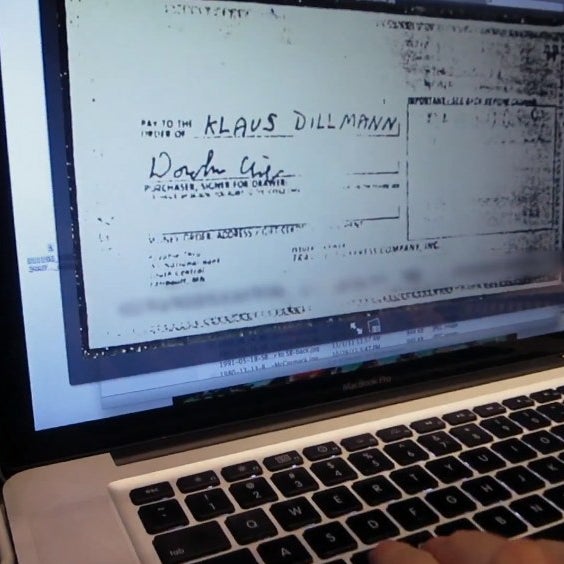

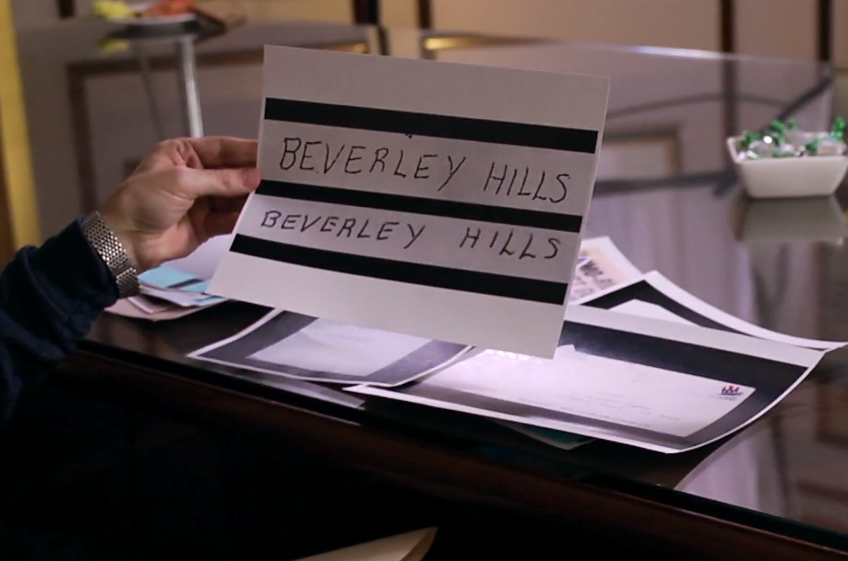

Let's start at the beginning. Before we get to the opening credits of Episode 6, we're reminded of the big reveal from the previous episode: the handwriting match between a letter sent to Susan Berman and a letter sent to the Beverly Hills Police Department, informing them that there was a cadaver at her address. We watch former Westchester County District Attorney Jeanine Pirro as she examines the handwriting samples and declares them the same, effectively inviting us to make the same conclusion ourselves — if we hadn't already by the close-up shots on the handwriting samples themselves.

Having established the firm suspicion of a handwriting match, the narrative cuts to the opening credits, which function as a music-video montage of footage from Durst's childhood (presumably provided by Durst himself) and recreations of events (some proven, some conjecture) from Durst's life. (The shots of Durst, as a child, watching his mother jump off the roof of their family home, for example, have been called into question by Durst's brother Douglas.)

In the opening credits, the camera films a man cutting his hair — and then cuts to an archival photo of Durst, with his hair shorn. The natural connection: That's Durst cutting his hair. Clearly it's not — Jarecki's cameras weren't there when Durst cut his hair and wore a wig to posture as a mute woman in Galveston, Texas — but the editing suggests that the "fictional" shots are simply re-creating actual events. The re-creations, in other words, have "truth claims": Even if you know, as a viewer, that they're re-creations, they're imbued with a sense of the real.

But they're also stylized: shot in slo-mo, with very particular lighting; there's a reason that people compare the credits of The Jinx to a fictionalized narrative like True Detective.

Apart from the prologue and credits, however, Episode 6 is devoid of the same sort of stylized re-creations. If the first five episodes were a semi-stylized take, this sixth episode is something completely different.

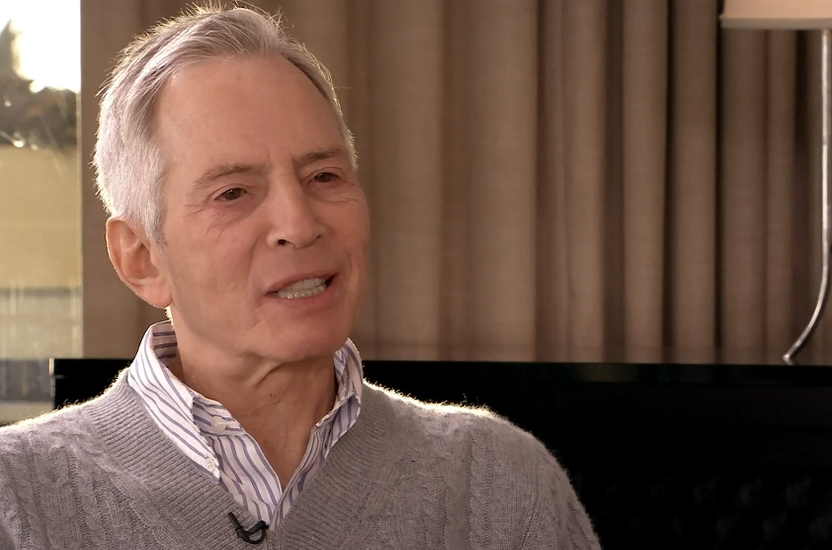

Until now, the shots above are the primary mode in which we've experienced our antagonist (Robert Durst) and our protagonist (Andrew Jarecki). Durst is wearing makeup, but looks fairly healthy. He's well-lit, and the gray sweater, the beige background, and the white of his shirt and hair make him look healthy for a man who would've been in his late sixties at the time of filming.

Jarecki looks formal, groomed, serious. He and Durst are almost always filmed in a shot-reverse-shot fashion, which means that Durst will answer a question, the camera will sometimes (but not always) switch to Jarecki asking or responding to him, and then return to Durst. Crucially, they're very rarely filmed in a two shot, in which both are visible in the frame together. It helps make their relationship seem formal, investigative, like an episode of 60 Minutes, not Oprah. It also makes it hard to determine whether Durst is actually answering the question Jarecki is allegedly posing to him in any particular scene.

We're reminded of this setup in the "Previously On THE JINX" sequence that begins the sixth episode: in part to set up the conversations that have brought us to this point, but also to emphasize just how different the relationship between Durst and Jarecki will seem when they sit down for the second time.

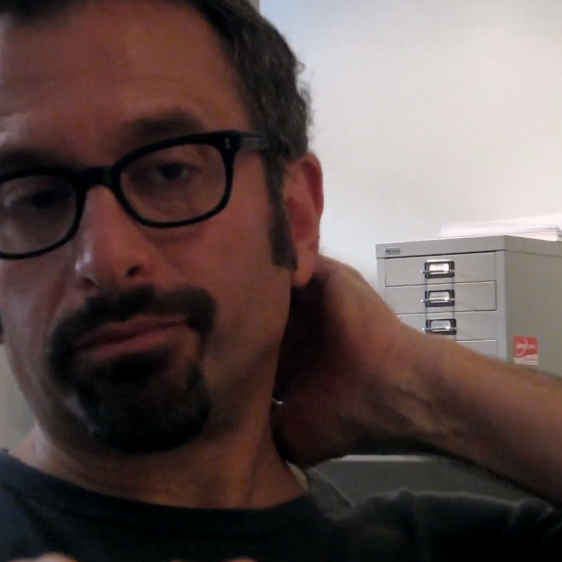

Take these first shots of Jarecki after the end of the title sequence of the sixth episode. The camera is unfocused; the sound is shitty; he's eating something. "Are you gonna record this now?" he asks.

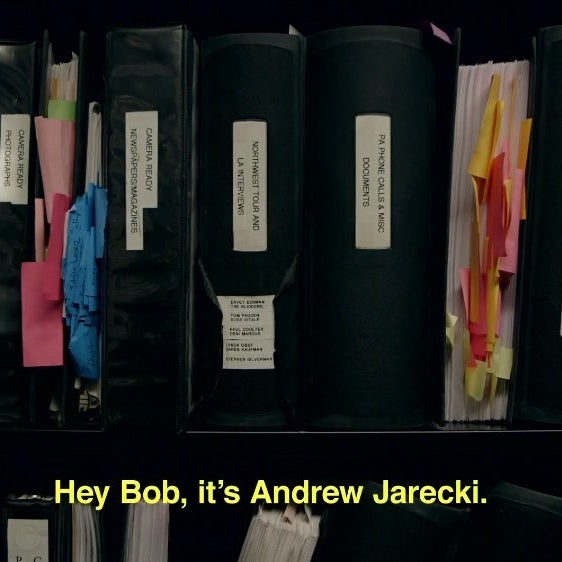

It's the beginning of a slew of sequences of what might be called "Jarecki and Producers Casually Plotting." They're dressed in T-shirts and hoodies; they're surrounded by a growing pile of beverages and file folders and steno pads.

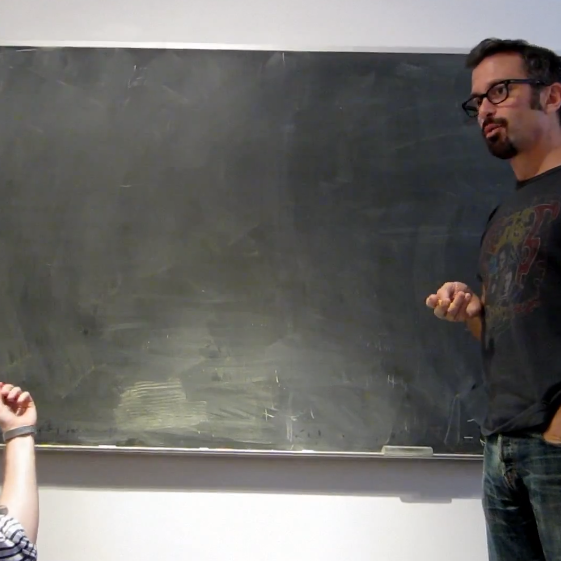

In the shot above, Jarecki's ostensibly writing goals on the chalkboard, but he's also working to inoculate The Jinx from potential critique that it's prioritized entertainment and ratings over bringing evidence to the police. Their number one goal, according to Jarecki, is "get justice." "So we don't want to interfere with anything that the police could do."

Then, a little bit of classic Establishing Authority: a shot of the handwriting expert's door to establish him as an expert; shot of him sitting in a dark room to establish general darkness.

A shot of the actual handwriting reproducing the point of view of the expert, followed by a shot of the expert. These shots, and the sequence of the additional handwriting search that follows, are simply reinforcing the conclusions that 99% of viewers would've held by the beginning of the credit sequence: Robert Durst wrote both letters and, by extension, Robert Durst killed Susan Berman.

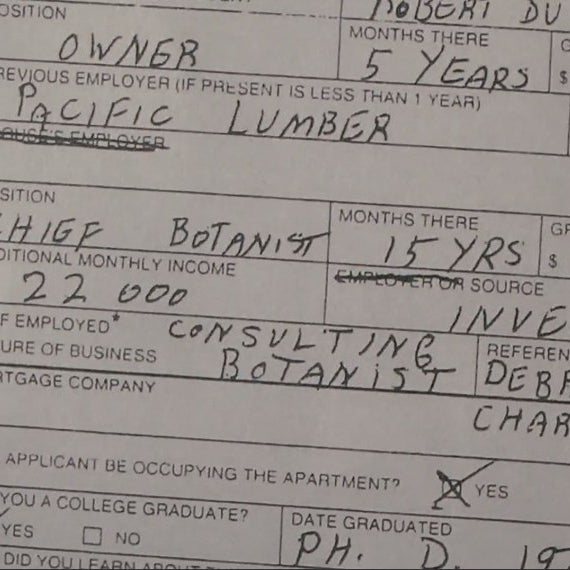

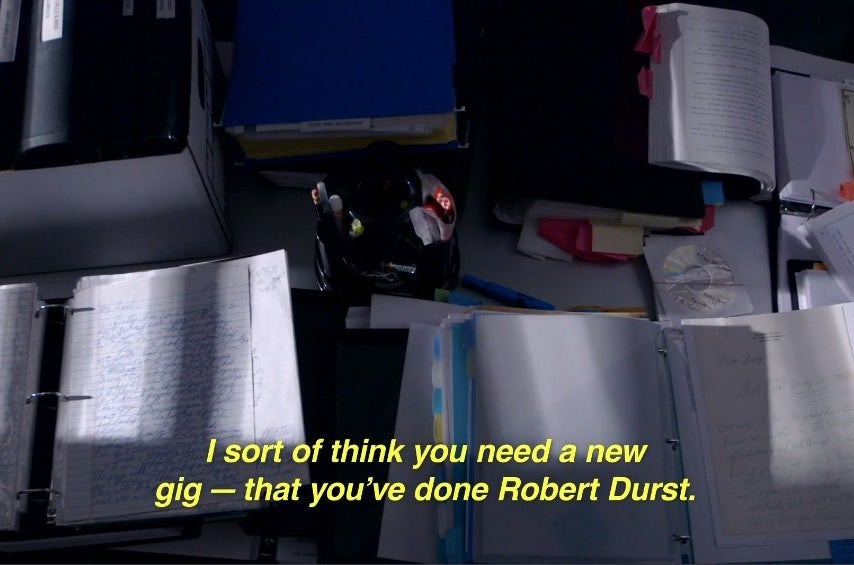

These handwriting scenes are doing more than simply padding the episode before we can get to Durst's interview. Like the scenes immediately before and after, they present the labor performed by the producers of The Jinx — not just the documents they unearth, but the documents on their computers as they unearth them.

Much like Serial — and more than in any of the previous five episodes — The Jinx is showing its "work," which makes it all the easier for the audience member to feel as if they're doing that same work and arriving at the same conclusions.

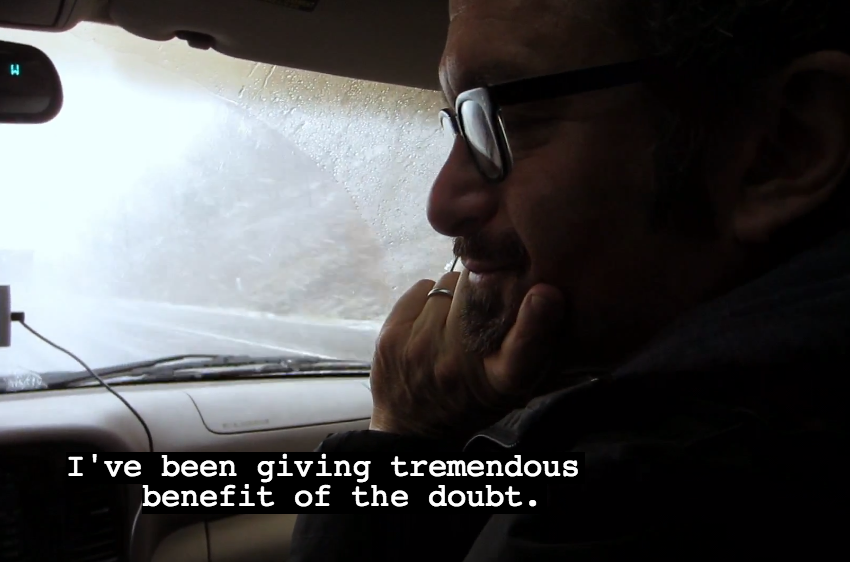

Cut to contemplative Jarecki in the bad weather car. The scene offers a slight moment of equivocation: acknowledging that Jarecki, like the viewer, may have had moments of doubt.

Why film this scene from the backseat, in the car, while traveling through a quasi-storm? First of all, it could've been filmed almost any time. Because we only briefly see Jarecki's mouth in motion, they also could have potentially edited and tightened the audio. But the exterior also lends a sense of impending doom, as if The Jinx is literally driving into the storm.

Last shot before The Storm. Good-bye, old, pal-y relationship. This particular still also suggests, fairly bluntly, that Jarecki and Durst have had different focuses/intents ALL ALONG.

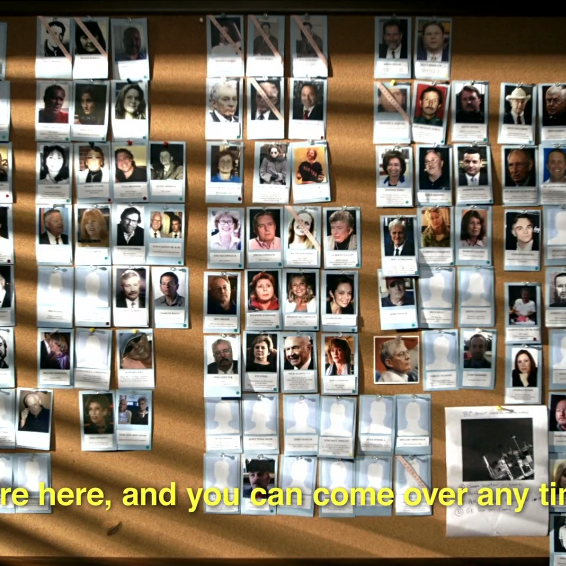

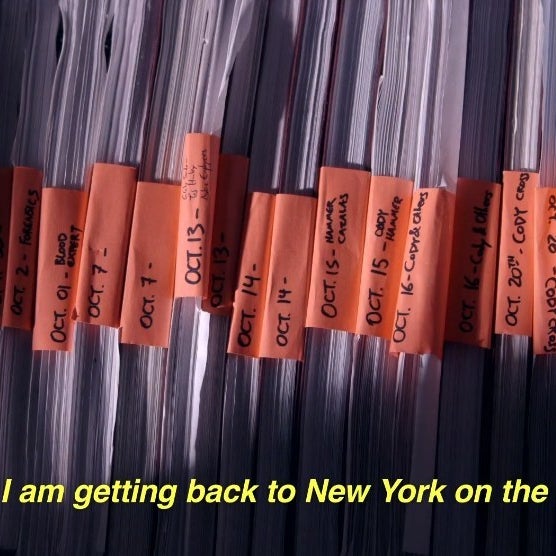

Before the storm, however, there's profound, elongated calm during which Bob repeatedly dodges Jarecki's attempts to coordinate a second interview. These scenes could've been incredibly dull, but the way they're shot and edited and intercut with tape of Jarecki and Durst's back-and-forth does something fairly incredible: It amplifies viewer animosity toward Durst.

It's not just Durst's lies, or his abruptness on the phone — abruptness that may or may not be the result of sound edits. It's the way in which that audio plays over the sun rising and setting on sets of investigative documents from the case.

Time is passing, of course, and Jarecki's threatening (halfheartedly) to start a new project, but the emphasis on the documents — and photos, especially — reminds the viewer that this isn't just about Jarecki's schedule. Human lives were lost. Durst's refusal to pin down a date for his second interview means those victims could remain pegged on that corkboard for an eternity of sunrises and sunsets.

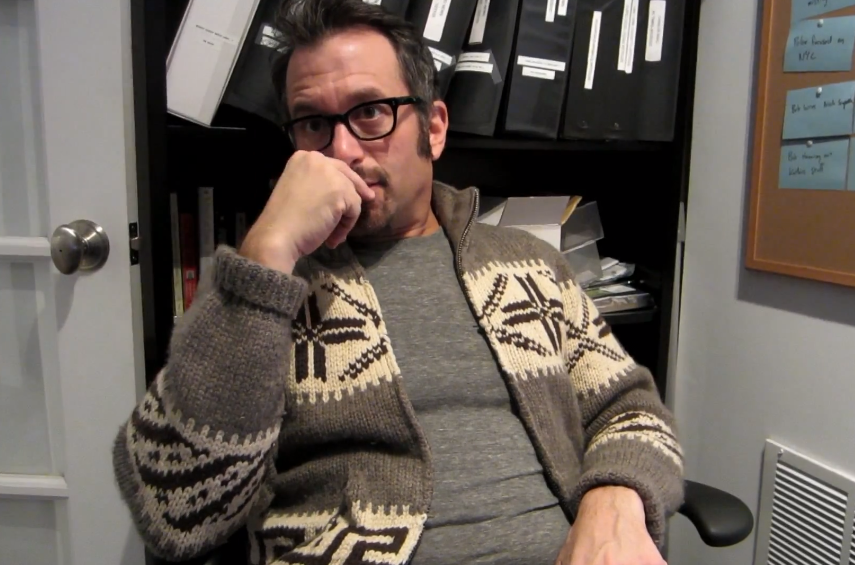

Concerned, casual, sweatered Jarecki concedes that Durst may never talk to them. Note how this scene is filmed: He's literally backed into a corner.

Durst seems to shut down the interview altogether, and the sun seemingly sets on the project at large.

Or maybe not!

The establishing shot of Jarecki's office is set at night — as if to pick up on the evening "setting" of the previous call, when Durst tells him that he should be "done with Robert Durst."

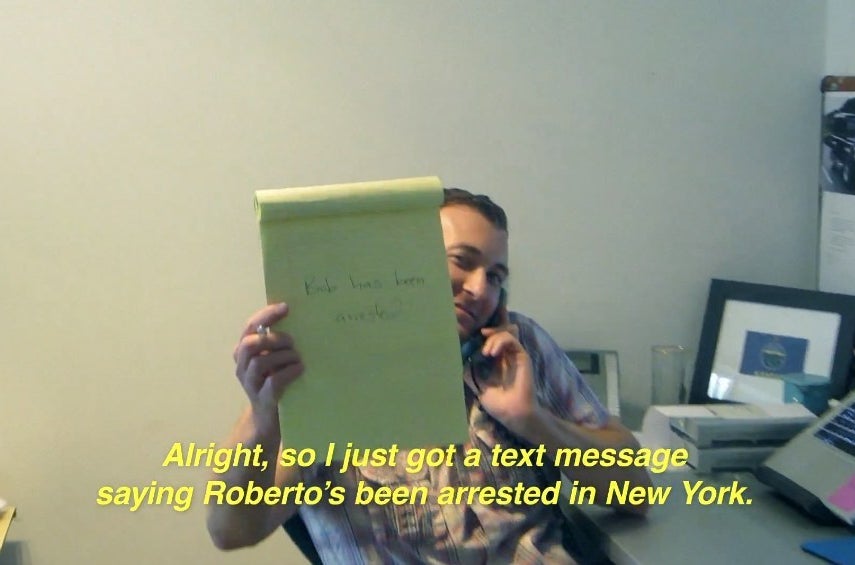

An odd set of edits, phone calls, legal pads (and the use of "Roberto" for Bob) lead the viewer to understand that Durst has been arrested for violating an order of protection taken out by his brother, Durst needs Jarecki's help to get off from the charge, and that Jarecki could exploit that leverage to get Durst to sit down a second time.

The timing here is all sorts of murky and manipulated: Durst was arrested in August 2013 — after, not before, the second interview, which took place in April 2012. That's been confirmed by a somewhat confusing interview Jarecki gave to the New York Times the day after the episode aired. And while Jarecki was careful to edit the episode to make it seem like the interview came after the arrest, a very close reading of it does confirm that the second interview came before the arrest.

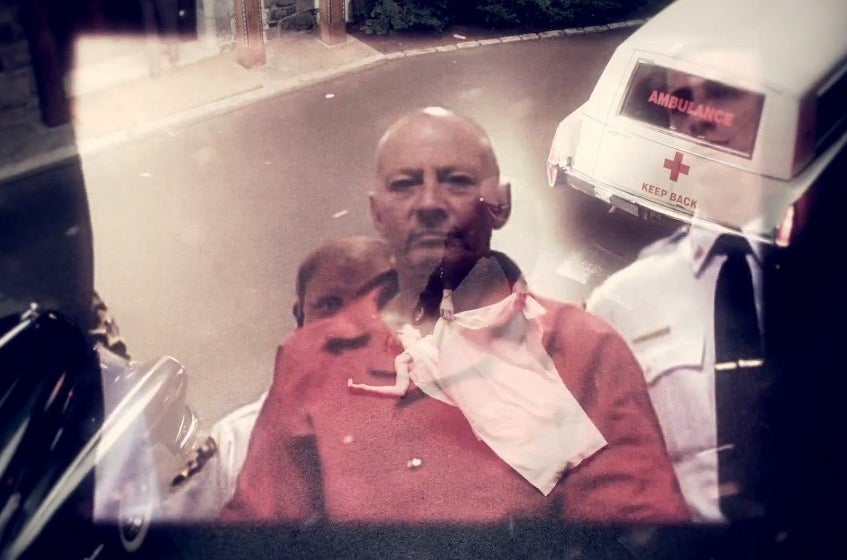

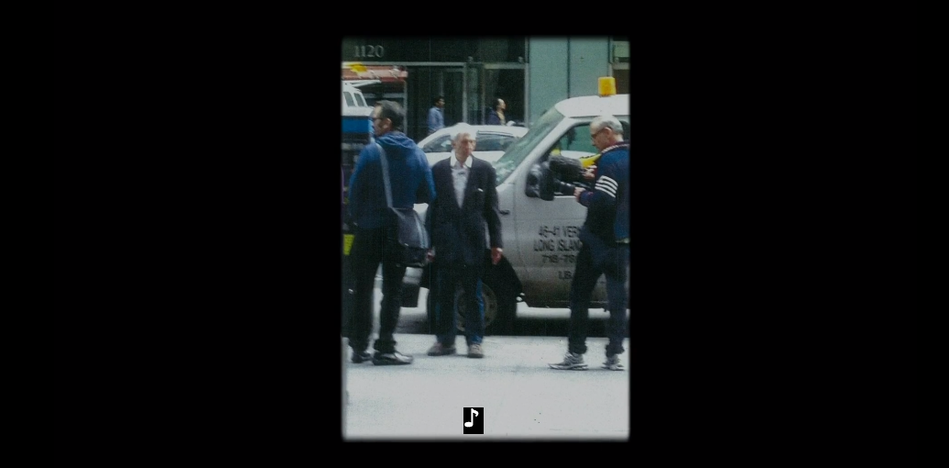

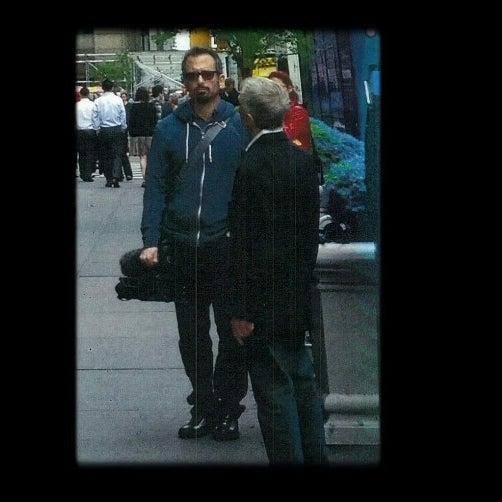

From left to right: Durst exiting after posting bail, the surveillance footage of Durst trespassing on his brother's townhouse, and a close-up of a newspaper article covering Durst's arrest. The next shots in the episode are of Jarecki agreeing to cooperate with Durst's lawyer and plotting the interview questions with his producing team.

Because this episode has made a point to draw back on the curtain on Jarecki et al's operation, there's little reason for the viewer to doubt this sequence of events. The lack of mediation, the rawness of the footage, has brought us to this point of trust.

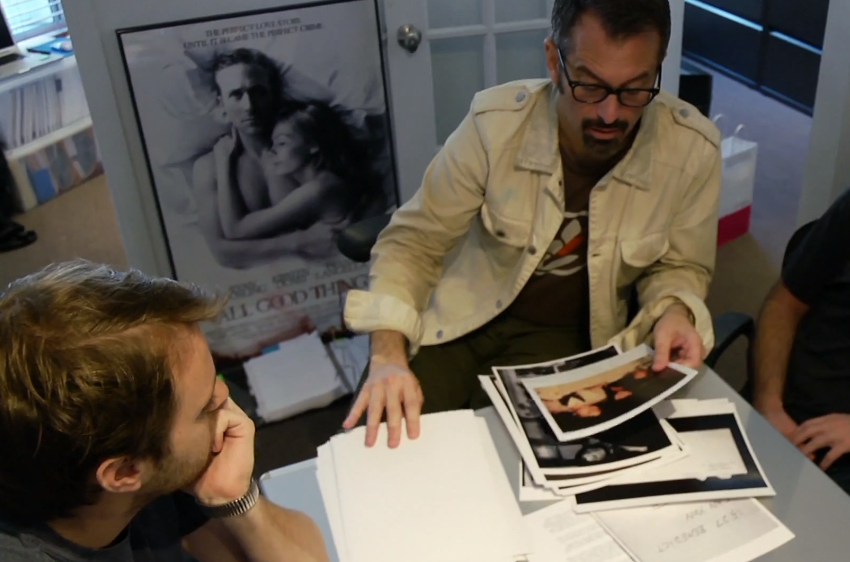

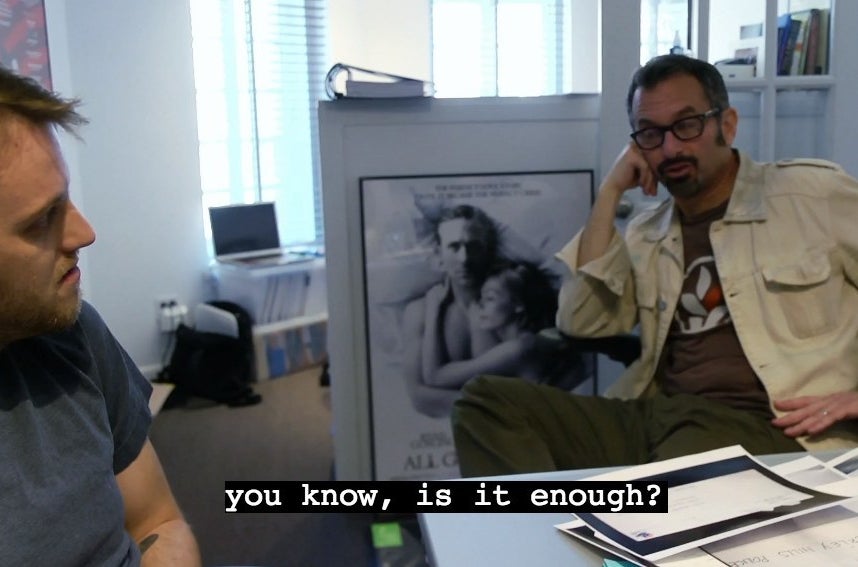

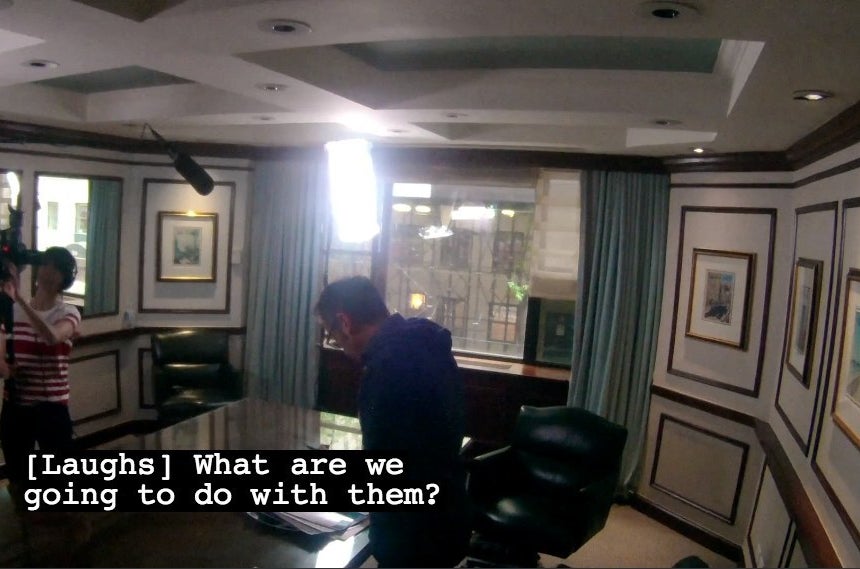

We're privy to the plotting of the interview, which not only makes us feel in on a plot — "here's how we're going to corner Bob," with the handwriting comparison — but also sets up a specific expectation for how the interview will proceed.

(Also note the presence of the All Good Things poster in the background of the frame. Nothing is accidentally placed in this series, and it works to remind the viewer, however subtly, that Jarecki's fictionalization prompted Durst's involvement. The Jinx, in other words, was never Jarecki's idea: It's all Durst's doing.)

Cut to a handheld camera pointed on the ground, walking into the hotel room that will host the second interview. It's a weird snippet of tape — two seconds at most — and easily could've ended up on the cutting room floor. Kept in, it again emphasizes the lack of mediation. The previous five episodes were beautifully, tightly edited and color-corrected, with full, gorgeous sound. This episode is uneven, sloppy, jostled, its subjects are poorly lit — more "real."

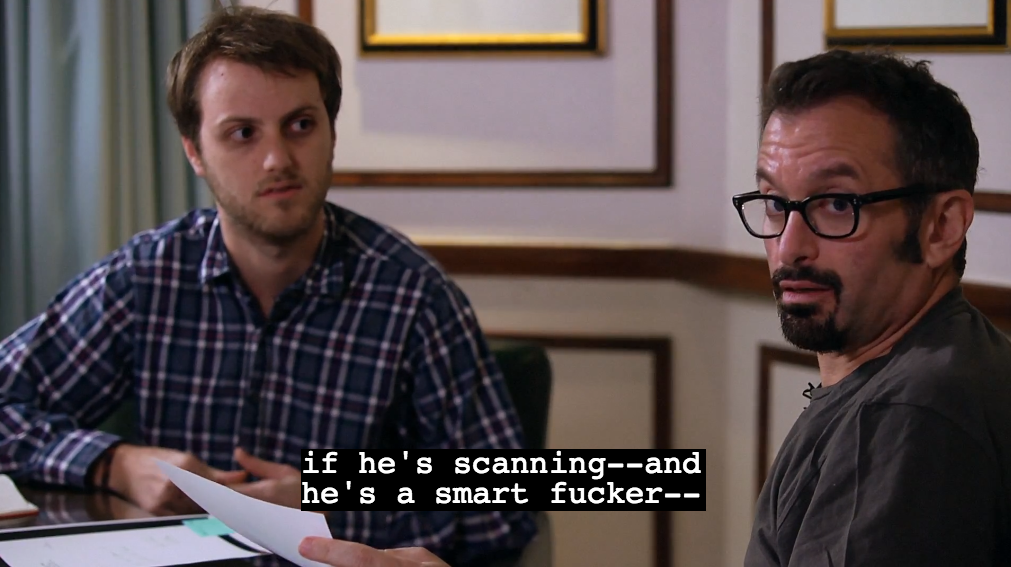

Rehearsing the interview, Jarecki reminds his fellow producers — and us — that Durst is a "smart fucker," effectively upping the fear, percolating across the entire episode, that he'll somehow figure out what they're trying to do and evade their questions.

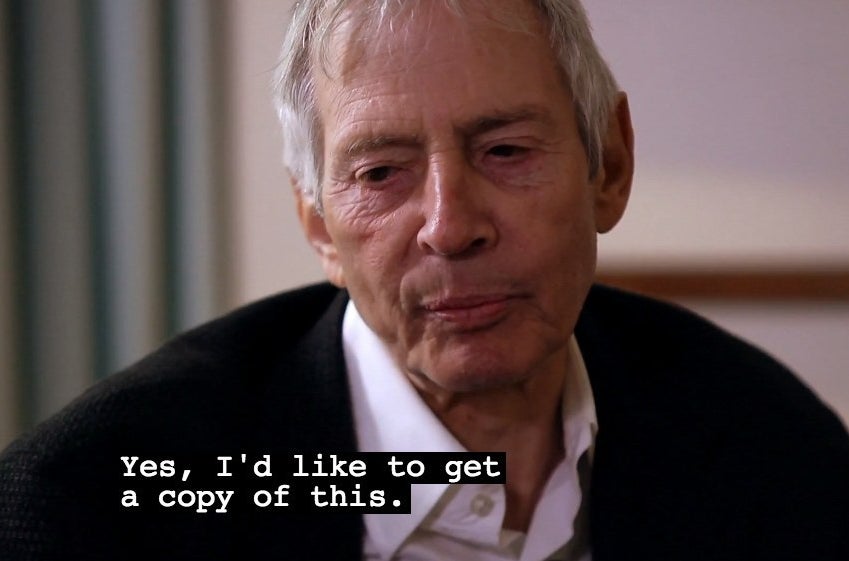

Cut back to the hotel lobby. A slow, hunched shuffle. Durst seems to have aged a decade in the handful of years since the first interview.

More handheld camera as Durst makes his way from the lobby to the hotel room, as if we're following him on a live-stream camera even though there are clearly moments (how'd they get to the hallway? when did Durst sit down?) edited for clarity.

Setting the stage for the interview: a dramatically different configuration than the two facing chairs of the first interview. They're on the same side, or at least Jarecki is attempting to make Durst feel that way. Jarecki's in a hoodie; he's far less groomed. Durst looks tired, and he doesn't seem to be wearing makeup.

And then there's the suit: the same suit he's wearing in the exterior shots below, in which Jarecki seems to be wearing the same hoodie. Which raises the question: Did they go and film exterior shots in Times Square after this second interview?

Take a look at these two stills, which show up earlier in the episode when Jarecki is discussing Durst's arrest after they filmed him in Times Square. Durst in a black suit and white shirt; Jarecki in a blue hoodie. We saw these shots in reference to the arrest, which supposedly happened weeks before the second interview. Here, it's clear that the second interview, and these photos, happened *before* the arrest. (Jarecki is now dodging questions concerning the timeline.)

So The Jinx's insinuated timeline is fucked.

But back to the interview, which is shot with a combination of two cameras: one pointed on Durst, which periodically zooms back to include Jarecki, and another roving camera that moves from shooting Durst and Jarecki straight on (across the table) and behind Durst's shoulder.

It's pretty classic film-editing technique for a conversation or interrogation — a shot of the two of them, a reaction shot from Durst, a shot over the shoulder as Durst looks at a document, another reaction shot:

The camera sticks with Durst through his answers, in part to emphasize his tics, tired eyes, and lack of modulation as they make their way through the stash of documents.

Here, in the second screenshot, the camera goes ever-so-slightly out of focus. There's a practical explanation: Durst was moving and the digital camera was struggling to auto-focus. But for the viewer, it creates a quick second of discombobulation, an understanding of this person and his testimony literally blurring.

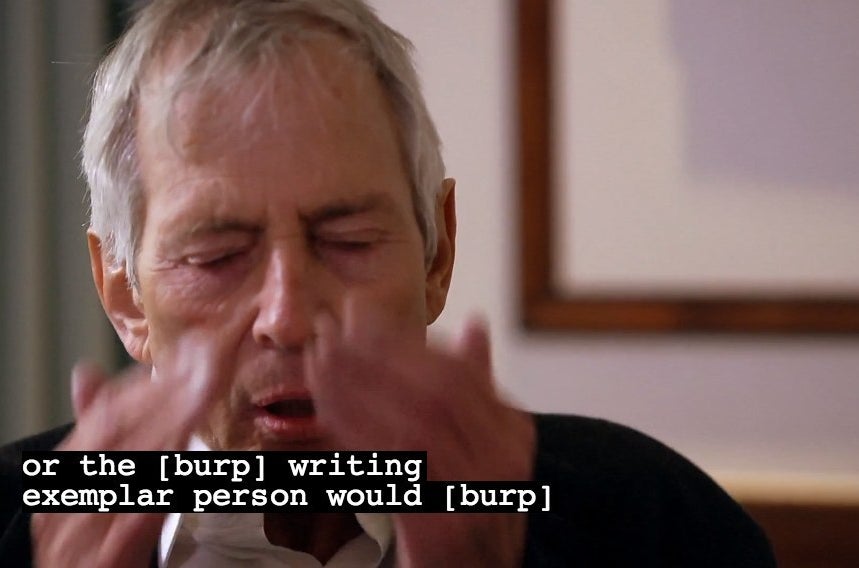

And then the long-held focus as Durst reacts to Jarecki's request to compare the two writing samples.

It's a purely astonishing second of film. His voice doesn't modulate; nor, really, does his face. His burping is a pure embodied reaction to the sight of the truth emerging — one that echoes the retching at the end of The Act of Killing when a central character was confronted with the same evidence of the atrocities of his past.

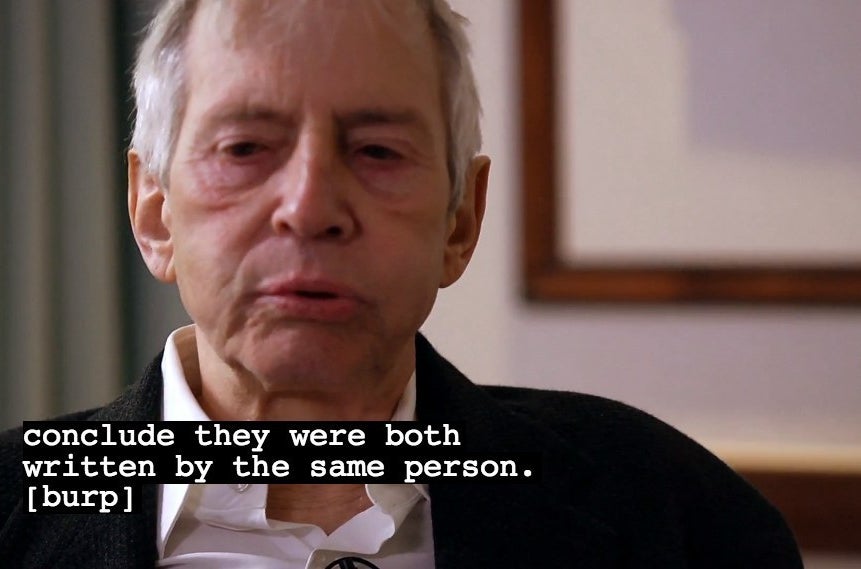

More remarkable, however, is how swiftly the conversation moves forward. Durst continues to deny that the writing is the same. We see the two samples from over Durst's shoulder underlining the depth of his deception: We're looking at the sample from Durst's point of view, and we can see, so vividly, the similarities of the samples.

The shot of the two samples centers itself — instead of looking at it through Durst's eyes, we're looking at it objectively — as Jarecki asks Durst to discern which sample is his. It's the sole deviation from the script we'd seen rehearsed previously in the episode, which makes it seem all the more clever, especially when it cuts to a reaction shot of Durst, unable to discern the two.

The camera stays on Durst's reaction even as the cameraperson swoops behind, presumably to get another over-the-shoulder shot. This might seem like a slight editing oversight, but recall that the entire interview has been shot to elide the presence of the camera, cutting back and forth when the cameraperson enters the frame. Yet this shot holds, even with her in the background: a signal that we're about to re-enter the (ostensibly) unmediated, unedited, unmanipulated space of the episode before the interview.

End of interview.

Or so we're led to believe. Jarecki starts shuffling his papers, Durst stands up, they say, "Thank you very much." The high angle and blurry focus make it seem like surveillance footage, simply recording all that happens (again, unedited, unmanipulated) before it.

Note, however, that Jarecki is clearly holding a vertically oriented news clipping, not the horizontally oriented handwriting comparison from the scene we're led to believe happened immediately before. This section, in other words, has been edited.

Here, a moment of comic sandwich-related relief...that also suggests that they're not editing, just collecting everything, even sandwich offers, that goes on in the background.

This surveillance-style tape rolls for a full 58 seconds before Durst enters the bathroom, effectively building a hefty narrative expectation.

The room clears; Durst enters the bathroom.

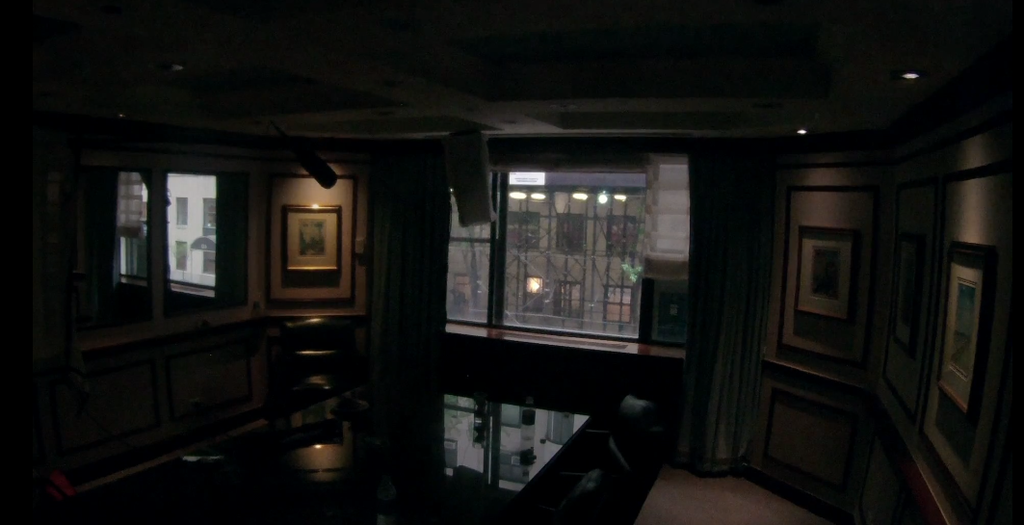

And then Durst's confession, intercut with groans, dispersed over 86 seconds, while the interview room slowly fades to black.

Between "killed them all" and all lights out: 24 seconds.

Between all lights out and the beginning of the credits: 47 eternal seconds.

The manipulation of silence is incredibly powerful here, but it's all the more so because the static, unchanging visuals force the viewer to concentrate wholly on the sound, which seems to build and contradict, switch mode of address, defend and chide before culminating in the one utterance that resists any sort of misinterpretation: "Killed them all."

I want to believe that that's the last thing Durst said before leaving the bathroom, that that was the last interaction between Jarecki and Durst, that that was the last piece of footage ever collected for The Jinx. That that was the end.

Clearly, it was not, even though no small portion of editorial agency has led us to believe otherwise. I resist the urge, however, to ascribe Jarecki and his team with some sort of guilt. All filmmakers, documentarians, and television journalists included, manipulate what's in front of them. Sometimes that editing is simply the process of selection — where do we film, who do we interview; other times it's in the editing room, or how they use titles and graphics and music to guide the viewer's understanding. (Jarecki has claimed that he did not discover the audio of Durst in the bathroom for two years.)

Ultimately, the question of Durst's guilt or innocence is one that no film can decide. The timing of Durst's arrest seems like a Hollywood ending (though the Los Angeles Police Department says it's not); either way, Jarecki certainly has turned up crucial new evidence in the form of an envelope. Now a jury of Durst's peers will figure this out; on Monday, Durst was charged with first-degree murder for the death of Susan Berman.

Documentary can educate. It can enlighten. But it's also an art and the product of humans and their very real prejudices, opinions, subjectivities. It's our responsibility to interrogate it with the same ferocity and mindfulness with which we approach any other attempt to transform the world around us into art that moves us.