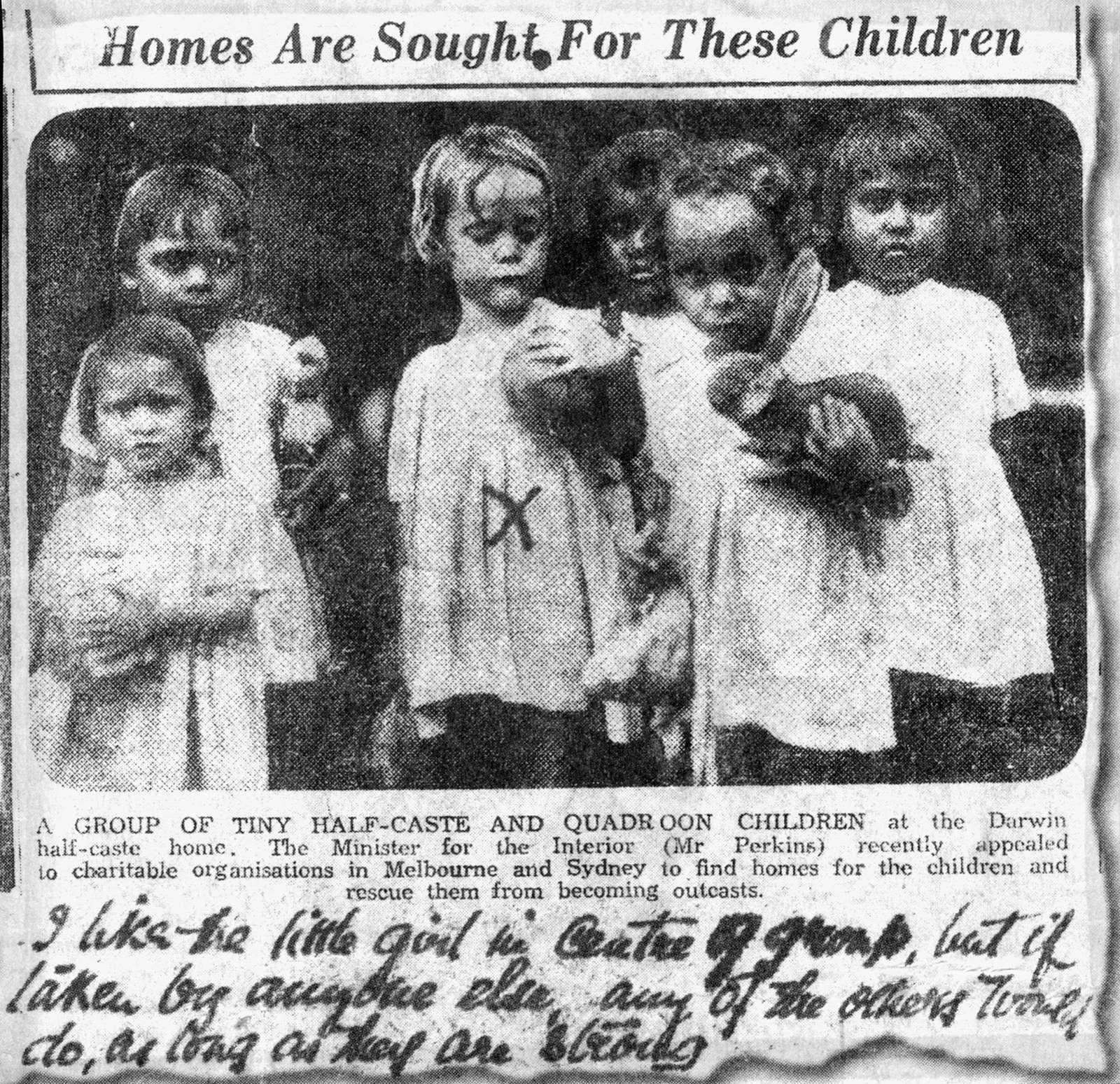

A terrible crisis is engulfing Australia's Indigenous community, with an entire generation growing up in government care. Tragically, this is a story that has repeated itself ever since Indigenous children were first snatched from their families almost a century ago.

That first generation of stolen children were denied their culture, were sexually and physically abused, and left behind a community traumatized for generations.

Now health experts fear it's happening again.

When the Bringing Them Home report was published in 1997, it found there were 12,363 children in out-of-home care, 2,419 of those were of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent. In 2014, there were 43,009 children in out-of-home care, 14,991 of which were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Koorie woman Nicole Cassar's family tree is stark testament that intergenerational trauma is an insidious, silent harbinger that spans decades and generations.

"My Nan, my mum’s mum, was removed and put in Ballarat orphanage. Then she had a child [Cassar's mother] who was removed and put in Ballarat orphanage, and then she has children who are removed and put in foster care and then one of those children [Cassar's brother] has a child who is now in foster care," Cassar says.

The removals started with Cassar's grandmother and have continued for four generations. It's a story reflected across the country, and in particular, in Victoria.

In the year to June 30, Victoria had the nation's second highest Indigenous child removal rates, ranking just below Western Australia.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders make up just 0.9% of the Victorian population, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, yet Indigenous children make up a staggering 17% of the out-of-home care population.

It's estimated there are currently over 1500 Indigenous children in care in Victoria, five years ago it was around 700. The numbers follow a similar trend around the country with a steady incline of removals in recent years.

In 1997, the Bringing Them Home (BTM) report laid bare the stark detail of Australia's dark history of forced Indigenous child removals and the ongoing impact of that trauma on families today. The BTM report, which would be the catalyst for former prime minister Kevin Rudd's historic apology, gave 52 recommendations to the federal government to ensure that stolen generation members received adequate justice and to safeguard against large numbers of Aboriginal children ever ending up in out-of-home care and detached from their culture again.

Despite an investment of over $100 million by the federal government, Indigenous children are going into care at record rates, to be raised as wards of the state, in foster homes and out-of-home care placements.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social justice commissioner Mick Gooda, writing in the annual Social Justice and Native Title Report released earlier this month, pleaded with the government to address the issue before it's too late.

"Greater investment is urgently needed in systems of accountability, research, long-term funding and the expertise of our agencies in order to address the overrepresentation of our children in out-of-home care. I am confident that these changes will go some way to improving outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their families," he said.

Members of the stolen generation were denied any semblance of their traditional culture. Those children old enough to know they that they were Aboriginal were punished severely for referring to it. Speaking their traditional language was forbidden. Aboriginal babies were raised by non-Indigenous families as white Australians. The profound fallout over this systematic denial of culture has today been widely acknowledged by the federal government and the United Nations.

However, despite the horrors of history, Indigenous children removed from their parents are still at a very high risk of losing their connection with culture. Health experts agree that there are several fundamental steps to ensuring the good mental health of Indigenous children removed from their homes.

These include ensuring a continued connection to country, the land from which the child's ancestors and family are from. The other main recommendation is to keep sustained contact with Aboriginal family members and to create an understanding of their kinship ties; this gives a valuable sense of belonging.

Today there are more Indigenous foster families and services to ensure cultural bonds with children in care. But still, most kids are placed into the homes of non-Indigenous foster carers, who often don't understand the importance of connecting them to culture.

In 2014, the Victorian Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People, Andrew Jackomos, and the Victorian Department of Human Services (DHS) formed Taskforce 1000, with a commitment to review the case of every single Aboriginal child living in out-of-home care in Victoria.

The Taskforce's aim is "to discover why Aboriginal children are in care, what the barriers are, as well as how to improve outcomes for the children through greater oversight of their plans and cultural, educational and health needs".

Since it's inception Taskforce 1000 has found that family violence is overwhelmingly the largest factor in child removals, with over two-thirds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children coming from a home with family violence, largely perpetrated by Koorie men. They also found that the violence is compounded by drug and alcohol abuse.

Today, Cassar, 48, is sitting in her cosy office in a corner of the cavernous Victorian Aboriginal Control Health Organisation (VACCHO) in the working class-cum-hipster suburb of Collingwood, Melbourne.

She talks bluntly about her childhood in the seventies and early eighties as a foster care kid.

"The system doesn’t look after you, it chews you up and spits you out and when you turn 18, just says 'good luck, we wish you all the best with you life'. When you are in care you think, 'I'll be lucky if I make it out of care alive and don’t end up in prison or the justice system'," Cassar says.

Cassar and her two siblings were constantly in and out of foster homes as children, watching on as their mother had a string of abusive relationships.

"I learnt from a young age that my mum wasn’t loved growing up and what she thought was love and security was the absolute opposite. The impact of mum's removal on my upbringing was that mum didn’t have the ideology about safety, and asking, how do you keep a child safe, and what is positive parenting, and what is a positive relationship," Cassar says.

In the 1950s Cassar's mother, Lynn Austin, was forcibly taken from her mother and placed in the care of a non-Indigenous, zealously Christian family in Geelong. There she endured horrific sexual and physical abuse until the age of 18. Austin's experience of abuse and foster homes would manifest itself in her relationship with her three children, of which Cassar is the oldest.

Two generations of Cassar's family, her grandmother and mother, were forcibly removed from their Aboriginal families and placed, in different eras, in the notorious Ballarat Orphanage, which later became the Ballarat children's home. Opened in 1909 and closing in 1987. The home has since become synonymous with unimaginable abuse and cruelty and the deaths of least 25 children.

That intergenerational trauma continues today with Cassar's four-year-old nephew, who is in out-of-home care, making him the fourth generation in her family to be removed by the government.

"My brother’s got a four-year-old and unfortunately, he’s four years old in shared care with me and my mum full-time. My brother's partner is also the daughter of a stolen generation mother and grew up as a VACCA (Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency) kid, grew up in residential care units and foster homes her whole life just like my brother," says Cassar.

In an office on the outskirts of Melbourne, the VACCA chief executive officer Muriel Bamblett is staring out toward the skyscrapers in the distance.

Bamblett is at the coalface of Indigenous child removals in Victoria. Her organisation is tasked with ensuring Aboriginal children within the system don't become another lost generation.

"Victoria has the highest rate of Aboriginal child removals and that challenges us," she said. "You know when Mick Dodson launched the Bringing Them Home report in 1997 he said, ‘if Victoria didn’t do something then those numbers would increase significantly in ten years,’ well it’s been 18 years and the numbers of kids in care has more than tripled, we’re almost quadrupling the number of kids so you’ve got to ask the question, what are we doing?"

VACCA was set up as a direct response to the high rates of Aboriginal children being removed from their families. It advocates for the rights of Aboriginal children and families, one of its main functions is to ensure that connection to culture is maintained.

"We run child protection programs so we work with the department [the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services] informs families of their rights and [attempt] to place Aboriginal children with family members wherever possible and we run residential facilities and a number of kinship care placement. The main aim is to keep kids in their communities".

The stolen generation is a stark warning of what happens when Indigenous children are denied their heritage. At present 60% of all Aboriginal child removals in Victoria are placed into the care of non-Indigenous foster families. Bamblett warns children devoid of culture are more likely to have mental health issues.

"If we say in two years time those 60% [of Aboriginal children in foster care with non-Indigenous carers] go home to their Aboriginal community what are they going home too?"

"They’re going home to a family they don’t know, they’re going home to culture they don’t have a connection too. They are so disconnected and they’re the kids that end up with severe and significant psychiatric issues. They’re dealing with the fact that they not only don’t fit into Australian society, but they don’t fit into Aboriginal society because they’ve lost that connection," Aboriginal Child Care Agency boss Muriel Bamblett.

Cassar managed to overcome the odds and is a now a successful health worker raising three sons, she wants the removals to stop with her family's next generation.

"I’m a survivor not a victim, but my brother and sister, who died at 21, unfortunately, were severely abused and they blamed mum. My brother still does, because mum chose to stay in a dysfunctional relationship and allowed her kids to be lost to the system because that’s what she thought her mother had allowed, so in her head she never thought, 'how do I stop this?'," Cassar says.

"I’ve been able to break the cycle, but when it comes to my nephew... I have three boys, 12, 16, 20, and we all have conversations with him to make sure he feels he has the right to thrive and succeed".

If you require assistance or would like to talk to a trained professional about the issues in this story, please call Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 or Lifeline(link is external) on 13 11 14. If you believe a child is in immediate danger call Police on 000.