PHOENIX — Inside, away from the 105-degree heat, the scene was intense: progressive activists, crying and expressing anger and disbelief, as undocumented immigrants and activists described in personal terms the grim realities of the border — skeletal remains in the desert, days without food and water, and deportation.

This was the plan.

The leadership behind Netroots Nation and immigration activists in Arizona wanted to acquaint the committed progressive activists who attend the annual Netroots gathering with the border-focused work the immigration activists do.

There in the offices of Puente Arizona, a local immigration advocacy group led by longtime activist Carlos Garcia, a group of committed progressive activists were bombarded with personal accounts by undocumented immigrants of harsh conditions.

Videos, created by Puente, were played of undocumented and mixed-status families talking about loved ones taken on their way home from work, or on their way to events requiring them to cross state lines. One video, by the family of Bertha Avila, was punctuated by her standing up in front of the room to tell the story of her six-month detention, after she was stopped at a checkpoint in California while traveling to a baptism.

In a black pantsuit, with her daughter by her side, Avila said she almost died in detention because of complications from asthma. The first five days were the hardest, because she was given no water, food, or asthma medication, she claimed. When she hit an emergency button, Avila said detention officers would yell, "What the fuck do you want?"

"I felt my life slipping away," she said, through tears.

Garcia, the group’s executive director, argued these kind of conditions ultimately stem from NAFTA, the expansive free trade agreement signed in the 1990s that broadened U.S. trade with Mexico that has seen renewed progressive ire this year as President Obama has tried to advance a new Pacific-based trade agreement. NAFTA spurred an influx of undocumented immigrants across the border — a development that produced increasingly strict immigration enforcement laws in the state of Arizona, culminating in SB1070.

It wasn't only Avila who became emotional, however.

Patrick O'Heffernan, the chairman of the Netroots Foundation, which helps fund liberal organizations, had tears in his eyes as he watched the videos and heard Avila speak. On a bus from Phoenix to Tucson after the event, he said he felt outraged that this could happen in America. "They're suffering and all they want is what everyone else in America wants, to have a better life," he said.

The bus stopped at the Global Justice Center in Tucson for a meeting with Coalición de Derechos Humanos (Human Rights Coalition), which serves as a liaison between medical examiner's offices and families, whose relatives have either died in the desert or lost contact.

Flanked by a rainbow-colored "We Are The 99%" banner, Isabel Garcia and her bare-bones, volunteer-driven organization said they receive 100 calls a month from families, and sometimes even calls from people lost in the desert.

Garcia, who debated Arizona Sen. John McCain on television 20 years ago about the effects NAFTA was having on Mexicans, painted a haunting picture of the realities for families who are faced with a death in the desert.

"Bodies become skeletal in two weeks," Garcia said. She told the story of a distraught father who couldn't believe the badly decomposed body he was looking at was that of his daughter. "He said it couldn't be her, then he turned her hand and saw the ring he had given her as a gift.”

Garcia discussed Operation Streamline, which was supposed to be part of the border tour but was cancelled last minute by the court, along with a visit to the medical examiner.

She talked about how immigrants who have reentered the country illegally are counseled to plead guilty by public defenders, and then brought in front of the judge in groups, where they are sentenced to detention and eventual deportation.

This was all too much for Lizz Brown, a criminal lawyer from Ferguson, and former special public defender. She said that lawyers violate their own ethics by telling their clients to all plead guilty and by not having 1-on-1 meetings with them.

For Brown, she was now on the other side of something that typically angers her — the oft-repeated refrain that "I didn't know" this was a problem.

"And now I'm there," she said. "I didn't know all of this stuff was going on."

She addressed the issue of blacks taking up the issues of Latinos or immigrants.

"As an African-American person there is a concern that our history is not used as a stepping stone for another movement," she said. "People are protective of their culture and history."

Garcia said everyone — from people of faith, to members of both political parties, to those with documents and those without — must do something about what is happening in the desert.

The bodies, she said, "they remind us of our inhumanity."

The border tour rumbled on to Eloy detention center, where undocumented women took turns speaking. Some had been in detention, and others had family members currently in the imposing sand-colored structure.

Claudia Amaro told the story of self-deporting with her husband when he was ordered to leave because they had never been apart. But in Mexico, she said, they were also undocumented and treated badly. She brought her son to a therapist where she was blamed for how she was handling the transition.

"Your son won't adapt to Mexico because you and your husband won't adapt," the therapist chastised. Amaro came to the U.S. as part of the DREAM 9 group who asked for asylum. Her case is still pending and she was released, but her husband Hector has been detained for 21 months while his asylum case is being processed.

Like many undocumented immigrants who have successfully worked with activist groups, Amaro is trying to leverage social media to get the word out about her husband. She held up a piece of paper with the words, "Yamil needs his dad," written in green marker, the name of her new Facebook page for him — and then everyone returned to the bus for the rest of the speeches. It’d only been 15 minutes, but it was too hot.

Back where the tour started, Robin Reineke of the Colibri Center for Human Rights talked about her work comparing missing person's reports to remains that have been found in the desert.

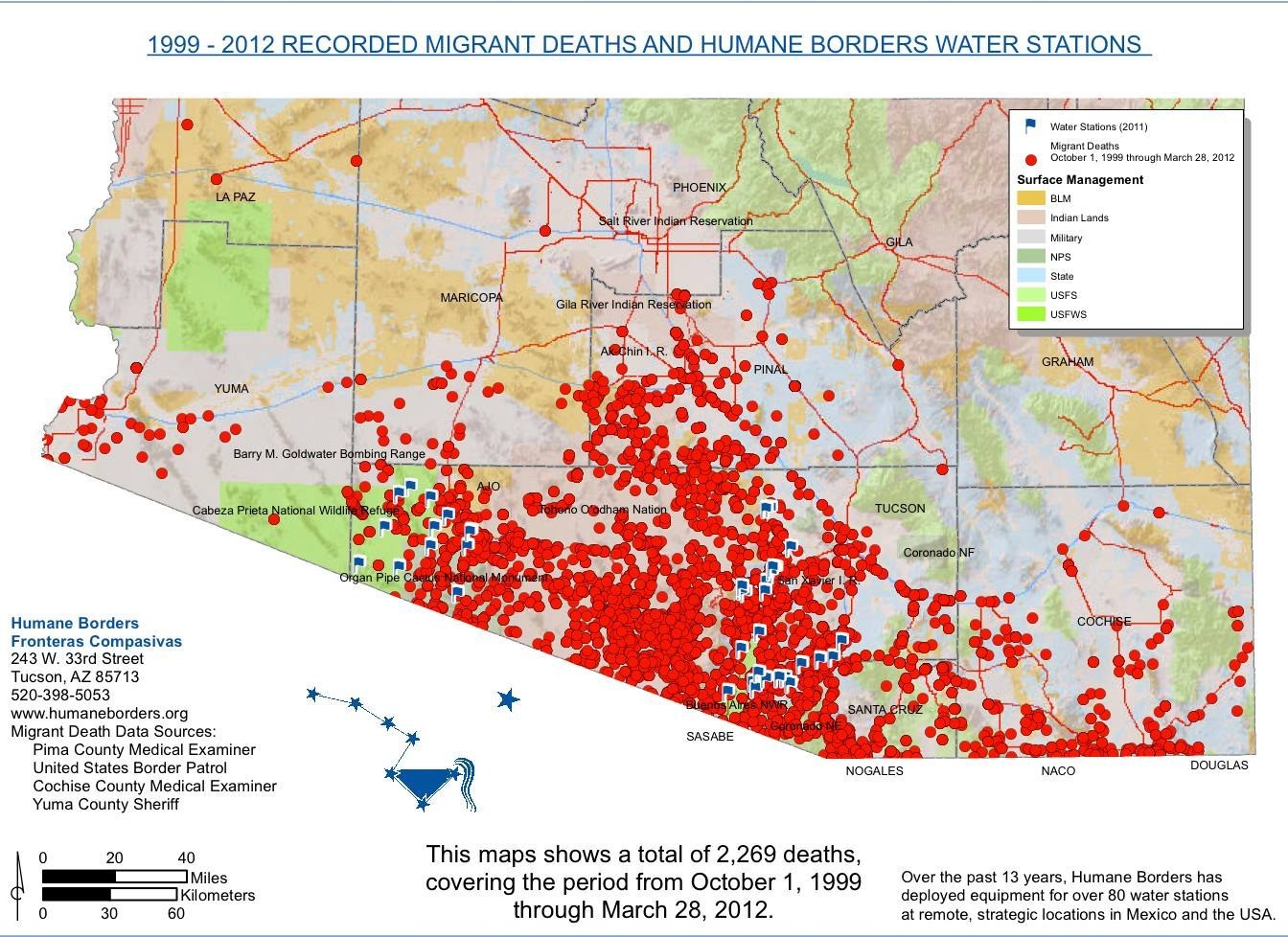

There were 2,269 bodies recovered from 1999 to 2012, with many concentrated in the Arizona desert. Not all bodies are recovered. There are currently 2,500 missing persons reports along the entire border with remains of 900 people in Arizona alone. "This is what happens," Reineke said, "when you put walls between families."

And then, in the air conditioning inside, after a nine-hour tour of the day, the progressives that Netroots had bused in for the event took turns saying what they had learned from this experience before the annual conference, which is meant to coordinate progressives. Several tied the experience to the issues they see in the criminal justice system.

"It sounds basic, but I didn't know it was so bad," one white activist said.

"Coming out of a year since Michael Brown, maybe we're living in a time where all of this that's going on is going to become inescapable for all of us," said Brown, the Ferguson lawyer.

"Everything is pushing towards some kind of firestorm. It's inescapable that we all have to do something."