Like so many true romances, Phil Lord and Christopher Miller first committed to each other with an act of profound cheesiness.

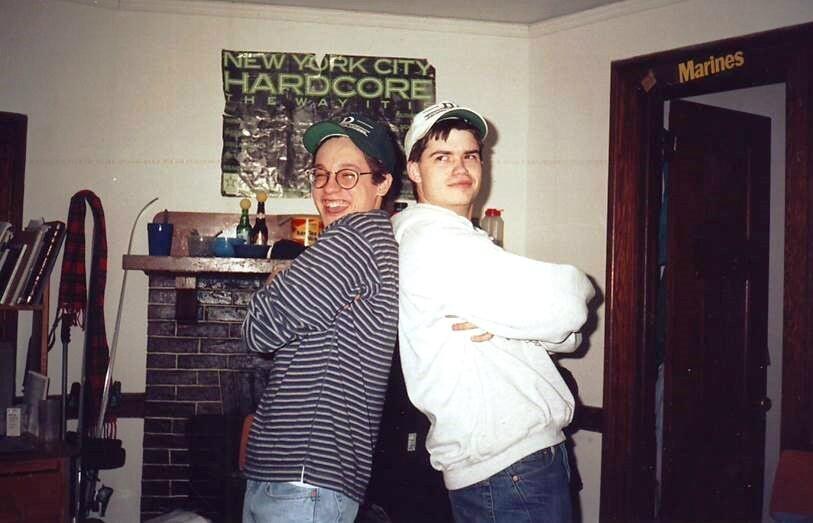

It was the summer of 1996, and Miller was interning at the visual effects house Industrial Light and Magic while living in what amounted to a flop house in San Francisco, the only affordable place he could find with month-to-month rent. Lord, his good friend at Dartmouth College, had flown out to visit for the weekend, and things were not going well. "It was a disastrous weekend," Lord says, rubbing his eyes underneath his black-frame glasses before sipping a margarita (on the rocks, with salt) in a packed New York City lunch spot. "I had, like, a sort of girlfriend—"

"—also visiting," Miller cuts in, sipping his own margarita (also on the rocks, with salt).

"—and Chris was living in, like, an office building, but the office part was prostitutes."

To escape, Lord and Miller decamped for Telegraph Hill, and found themselves standing at the top of the Coit Tower. They had both just finished their junior year at Dartmouth, and they were staring down an uncertain future, amid classmates with very different pursuits than the countless hours they had been spending together making their own animated student films. "All our friends were interviewing to see who got to take down the world financial system," says Lord. "And they did it!" adds Miller.

The notion that they could somehow become professional filmmakers, however, had felt to them as murky as the fog choking the Golden Gate Bridge. But in that moment, standing together atop the San Francisco Bay, with an earnest emotional flourish only college undergrads can muster, the fog over their future lifted.

"We both had this super-lame moment at the top of the Coit Tower, looking out [at the Bay] and saying, 'You know, I think we can make a go of making stuff,'" says Miller. "'I think we can do this.'"

"It's like a Nicholas Sparks novel," says Lord.

"And so we decided to move out to Los Angeles and" — Miller moves his hands dramatically — "try to make it in showbiz!"

Suffice it to say, they’ve definitely made it. This week, Lord and Miller walked a raucous red carpet for the premiere of 22 Jump Street, their fourth feature film as directors in what has been one of the most auspicious and enviable career trajectories in modern Hollywood. They were recruited by Disney right out of college; created their own cult hit animated TV show in their mid-twenties with MTV's Clone High; began directing their feature film debut at 30 with Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs (based on the popular children's book); launched romance himbo Channing Tatum as a bona fide comedy star with 21 Jump Street and its sequel (based on the popular '80s TV series); and, with $462.3 million and counting, made one of the most successful films of 2014 with The LEGO Movie (based on the popular toy line).

That alone would be impressive, but all these feature films could easily have also been typical examples of slapped together, mediocre "product," spawned by Hollywood only for their brand-name value. Instead, Lord and Miller have made each of their films richly and delightfully weird, filled with the kind of smart, sharp edges that most studio films have aggressively sanded down. "You kind of can imagine the usual version of those [movies]," says Bill Hader, who voiced the wild-haired, mad scientist lead in Cloudy. "They're properties that studios want made, and so it's like, Oh, I see what that's gonna be. But with Phil and Chris, it goes through their filter, and they go, 'Nah, we're gonna make it ours.'"

"I can hear their voices in every single iteration of their creative process," adds Barry Blumberg, the former Disney executive who gave Lord and Miller their first job in Hollywood. "When I watch The LEGO Movie, or Cloudy, or 21 Jump Street, I can hear those guys talking. I can hear them pitching out the ideas."

With 22 Jump Street, Lord and Miller, now both 38, have pushed their silly-smart sensibility even further, crafting a comedy sequel that knows it's a comedy sequel — jokes about recycling the same story over and over again and needlessly boosting the budget abound. But they don't dominate. The film never curdles into an arch, ironic meta-joke, because Lord and Miller keep the story laser focused on the central relationship between Tatum and Jonah Hill's undercover cops, two straight dudes who are perfectly matched and hopelessly devoted to each other. Kind of like Lord and Miller themselves.

"We know from being in a partnership that it's like being in a marriage," says Miller (who is actually married, to his college girlfriend, and has two small children). "It really is like being in a romantic relationship."

"You get your feelings hurt in the same way," adds Lord (who lives with his girlfriend). "Without the sex."

As a pair, Lord and Miller certainly complement each other, Miller more soft-spoken and deferential, with a head of rigid helmet hair; Lord more direct and demonstrative, his hair an unruly tangle of curls. Over a two-hour lunch before a special New York screening of their latest movie, they revisit the wild, winding story of how they've become Hollywood's go-to filmmakers for quirky, popular movies based on crass, questionable ideas — and they certainly behave like a married couple too. They finish each other’s sentences, tell stories about each other, even make sure to watch each other speak amid the noisy din of the dining New Yorkers around them. It's adorable. And instructive. These two genial nerdy guys have managed to conquer the Hollywood system while remaining steadfastly outside of it — due to their talent, their dogged work ethic, and, most importantly, the fact that they have each other.

Lord and Miller grew up on opposite corners of the country — Lord in Miami, and Miller in Seattle — but otherwise (and perhaps not surprisingly), their childhoods followed quite similar paths. From a young age, they were both obsessed with animation. "When we were kids, we watched a lot of Chuck Jones cartoons," says Miller, speaking for Lord's childhood as well, even though they didn't actually know each other until they were 18. "He was a huge part of our existence, like, doodling in class instead of taking actual notes. I tried to make my own animated thing with my parents' VHS recorder — start stop start stop. It was not very good."

Lord, meanwhile, started attending underground animation festivals when he was in middle school. "I was probably 13 years old," he says. "There was an ad for a tiny art house theater and they would collect all these animated shorts from around the world and compile them together every year." He drank in the deadpan absurdity of films like 25 Ways to Quit Smoking by Bill Plympton — whom Miller would later intern for — and Matt Groening's very first shorts featuring The Simpsons — which were also blowing Miller's mind as they played on Fox's The Tracey Ullman Show.

"There's a subversive quality to all the stuff that we really like," says Miller. "You could do a type of comedy that you couldn't quite get away with in live action for being too broad or arch. It was a way to be kind of extreme and satirical."

"It's a combination of nerdy things to get to the nerdiest possible thing," adds Lord. That love of un-cool things extended into live-action films as well. Both recall owning only three VHS cassettes at home growing up, and they hint at both their respective personalities, as well as their subsequent shared creative sensibility. For the buttoned-up and even-keeled Miller, it was Star Wars, The Wizard of Oz, and Singin’ in the Rain. For the energetic and expressive Lord, it was Star Wars, Howard the Duck, and the Robert Altman Popeye.

Their gravitation toward pop-culture nerddom was also informed by their figurative and literal small stature within their respective private high schools. "It took forever to get any kind of social status," says Lord, turning to Miller. "You were short until your junior year, probably. I was short until my senior year. It's just, like, your social status is so dependent on how quickly you hit puberty, basically."

Today, both men are remarkably devoid of the kind of social awkwardness that often sticks to high school nerds well into adulthood. They share an easeful, jokey rapport in conversation, no more so than with each other, where even discussing the moment they first became friends their freshman year at Dartmouth can quickly break down into a cascade of overlapping teasing.

Chris Miller: We knew each other a little bit before then. But the big event—

Phil Lord: —what really cemented the relationship—

CM: —was his girlfriend lived downstairs from me. We were good friends, and I was in her dorm room, and she was playing Tetris, and I was playing the game called Let's See How Close I Can Get This Lighter to Her Hair Without Her Noticing. And I won because her hair caught on fire and she still didn't notice until I put it out.

And Phil, were you there?

CM: No.

PL: No, I think I was there!

CM: You were not there! Afterward, you were like, "You're the one who made my girlfriend's hair smell bad!"

PL: I induced a memory of it?

CM: Yeah, you were definitely not there. But you were there for the aftermath, and the fact that you thought it was funny, and you didn't, like, get aggro at me made us friends.

PL: I'm sure I was there. Obviously, one of us is wrong. It's obviously Chris.

CM: (Laughs)

PL: But I have a very visual memory of what that was like. Maybe from just telling the story so many times. But yes, she's fine. She's doing great now.

With so much in common, the two bonded pretty much immediately in the way that only 18-year-olds with a lot of sudden free time and freedom can. Miller was a government major, but Lord — who bounced through majors as disparate as computer science and art history — convinced Miller to take a class in animation together. ("It was the least academic pursuit that you can possibly go for," says Lord with a cheshire grin.) Eventually, they started making their own student films side by side, each providing advice and counsel to the other.

"We got course credit for it," Miller says. "It took over our lives. The college gave us a studio that we could work in, which was right next to career services, where everyone was coming in to work at JPMorgan, walking in [with] their suit and a Wall Street Journal while we were in our T-shirts and underpants playing loud music and drinking Jolt Cola to stay awake."

When Miller starts describing Lord's film as "really cool, actually, visually awesome," Lord begins vigorously shaking his head before finally jumping in. "Visually interesting, slow, painful," Lord says. "It was eight minutes long. For animation, that's like, you better win an Oscar at that length. It was called Man Bites Breakfast, and it was breakfast from the cereal's point of view. It's very college-y."

Miller, meanwhile, was adapting his comic strip in the student newspaper — called The Sleazy the Wonder Squirrel Show, featuring the titular chain-smoking talk show host and his sidekick, Herschel the Hasidic Hamster — into a few animated shorts. "There's one where their guest is supposed to be Godot, but he never shows up, so they go to France to find him and kick his ass," Miller says. "It was very Ahhhhh, highbrow and lowbrow at the same time!" He winces. "It was so weird and pointless." Lord immediately interrupts, speaking directly to Miller with an almost reproachful tone: "It was very clever."

Miller's comic strip also turned out to be the the catalyst for the duo's first big break in Hollywood, a stroke of luck so outrageously fortuitous that Miller still can't quite believe it really happened. His senior year, Dartmouth Life magazine — a tabloid-size alumni magazine, or as Miller puts it, "alumni propaganda" — published a cover profile about Miller and his strip, greatly elevating Miller's accomplishments in the process. "The article says stuff like, 'At his internship at Industrial Light and Magic, he helped design the dinosaurs for the upcoming Star Wars prequels,' which is wrong for lots of reasons," says Lord with a laugh. "He got coffee for the guy who made the not-dinosaur. It's like when you tell your mom something, and then she tells your grandma, and then she tells your friend, and then suddenly you're directing the sequel to E.T."

Unbeknownst to Lord and Miller, they were attending Dartmouth with Eric Eisner, the son of The Walt Disney Company's then-Chief Michael Eisner, one of the most powerful executives in Hollywood. "Apparently, apocryphally," says Miller, his eyebrow still cocked in suspicion, "[Michael Eisner] saw this article and passed it on to someone, who passed it on to someone, who passed it on to someone, who ended up passing it on to Barry Blumberg, who was the head of Disney Television Animation," says Miller.

It was not apocryphal — Blumberg confirms that's exactly what happened. In fact, Blumberg called Miller in his off-campus apartment to offer to fly him out to Los Angeles for a meeting. "I didn't really know what we were going to do with them, but I knew they were great," Blumberg says now. But first he had to get them to L.A. "I was like, 'Argh, I've got midterms! I'm busy!'" says Miller. "'But my buddy Phil and I are planning on moving out there in the summer, so I'll just save you the money and we'll meet in the summer.' It shows you how savvy I was. I was playing hard to get."

"We talked hard about it," says Lord. "Midterms is, like, a really good reason to delay a career-defining meeting with the biggest animation company in the world."

When they did finally take their meeting with Disney, Blumberg simply presumed that because Miller and Lord had come into his office shoulder to shoulder, they were professional partners. But despite their declaration at the top of the Coit Tower that they would strike out to Hollywood together, they had never actually collaborated on the same project. "They came across as a team," says Blumberg. "Maybe that's in friendship, and sometimes in friendship are formed great partnerships." He hired them together into a development deal. At just 22, Lord and Miller had landed their first paying job in showbiz.

In their first year as part of the team at Disney Television Animation, Lord and Miller estimate they pitched roughly 40 different shows. "We were scared to death," says Lord. "We were like, These guys are paying us thousands of dollars. We've got to get them their money's worth."

As good friends as they had become, however, sorting out how to work together on the same project did not come easily. "The first year was particularly challenging," says Miller, "as far as, like, us both being used to doing our own thing — getting input and help from the other person but, at the end of the day—"

"—making the choices [ourselves]," says Lord, jumping in. "Having the power makes you more generous. When you don't have the power, suddenly you get defensive, because it's not up to you, you have to convince the other guy." He smiles. "It's infuriating."

Not one of their pitches, meanwhile, made it on the air. It was a period of great expansion for what a "Disney" project could be, from Lizzie McGuire to the Pirates of the Caribbean films. But Lord and Miller's heady mix of silly erudition still didn't jibe even with the (somewhat) looser boundaries of the Disney brand. "One of the first things they produced never saw air, but it's one of the funniest things I was ever associated with," says Blumberg. For the variety series One Saturday Morning, Lord and Miller cooked up a commercial for a toy line of famous literary figures. "They had made action figures inspired by the Brontë sisters," says Blumberg. "They were like Transformers, so the three Brontë sisters could come together and form the Brontësaurus." He still chuckles at the memory, but he says he could not get it through the Disney system. "Whoever the powers that be were above me did not get it. People just didn't know what to do with that."

Lord and Miller could achieve that level of freewheeling absurdity largely because, as Blumberg puts it, "We left them to their own devices," a circumstance that's become something of a motif for Lord and Miller's entire career. "We really had a lot of faith in the creative process, and we sort of let people have a lot of free rein." But eventually, Lord and Miller moved on — even their well-received pitch to create an animated version of the long forgotten live-action Disney film The Cat From Outer Space ultimately didn't pan out. (Ironically, they did make it on TV, but as actors on the NBC sitcom Caroline in the City, where their near-mute characters, also animators, sparred in their drawings over who would get to date Lea Thompson's lead character. "We had just gotten a lawyer, and he was like, 'Guys, you can't have your animated likeness be given away to Caroline in the City in perpetuity,'" says Miller. "So we had to change it to ferret versions of ourselves. It was very embarrassing.")

After bouncing through a few writers’ rooms on some failed late '90s sitcoms, Lord and Miller realized they were a little adrift. "We knew we needed a more experienced person to help us navigate the waters," says Miller, and that's how they ended up sitting in front of Bill Lawrence — a TV writer seven years their senior, who was just launching his NBC live-action series Scrubs. "It was weird for me because it was the first time I was ever put in kind of a supervisory, mentor-type thing," says Lawrence. "Those guys came in more mature and more talented than I was. It was really upsetting."

Their pitch to Lawrence was in the same vein of the kinds of shows that hadn’t quite flown at Disney, a fabulously bizarre animated teen soap opera called Clone High. The premise: A cabal of shady government types have cloned famous figures throughout history — including Abe Lincoln, Joan of Arc, Cleopatra, and JFK — and now they are hormonal, moody teenagers living together in high school, plagued not only with adolescent angst but the pressure to live up to their historical doppelgängers. It was… a lot, but it was also undeniably compelling, especially coming from two young guys eager to finally get a show on the air.

"I connected to them even more than the idea," says Lawrence. "I was just like, These two guys seem to be slightly insane. Hollywood is just a town where you never know who's gonna be your boss a year from now. I was smart enough to know, these guys are gonna be giant Hollywood players, and it's best for me if I just nod and say this is a great idea."

The show was picked up by MTV amid the post-South Park fever for more adult-skewing animated fare. They were put on such a shoestring budget that, to save money, Lawrence smuggled the entire production onto the abandoned hospital where he was shooting Scrubs and set them up in the psych ward because no one else wanted to be there. Once again, Lord and Miller were largely left to their own devices, as they supervised the writers’ room, drew storyboards, edited scratch animation, and voiced several characters. They would spend hours obsessing over individual frames to get the comic timing of a single joke right.

"First of all, they're both giant, giant nerds," says Lawrence, "[but] they aren't awkward-looking in real life, just when they get their photos taken." He laughs. "What I was impressed with about those guys was they made each other laugh, but they both have completely distinct voices that really kind of compliment each other. I think that's a rare thing."

After having their ideas shot down so often, they also imposed a rule that has become a defining touchstone for their career. "We want to say yes to everything that we possibly can," says Lord. "If there's a crazy idea, let's see if it can work. And more often than not, it led us down really fun roads and ended up being worth it."

In fact, they say they really received only one consistent note from their bosses at MTV: Their audience won't know who these characters are. "They kept saying, 'You don't understand, they're not as smart as you think,'" Lord says, laughing.

“‘They don't know anything,’” says Miller, jumping in. "'They don't know who Marie Curie is!'"

"We didn't really care," says Lord. "A lot of times, we would say someone's first and last name for no good reason. 'Oh, Sigmund Freud!'"

"'You godfather of modern psychology!'" says Miller, with an aw shucks arm swing.

Unfortunately, there were people who were acutely aware of at least one character on the show: Gandhi, whom Lord and Miller transformed into a hard-partying, skirt-chasing horndog teenager desperate to escape the saintly reputation of his genetic predecessor. Lord and Miller say they never once thought the character would be controversial — "We were worried about Kennedy, because we thought the Kennedy family is powerful," says Lord — but when news began to break in India that an MTV show included a highly irreverent version of the most revered man in the country, serious outrage soon followed. Hunger-striking protesters, including Gandhi's grandson, ended up taking over the MTV offices in India the same day Tom Freston, the head of parent company Viacom, was visiting. The show was pulled off the air the next day, and it never came back.

"They were of course crushed," says Lawrence. "What I don't think they realized at first was doing that show was without a doubt a great thing. Within the industry, it made people go, 'Wow, two guys in their twenties not only wrote and produced a show this high-quality, this edgy and different and funny, but actually animated it as well.'"

After such a promising start, Lord and Miller's first five years in Hollywood had been rocky and riddled with disappointment, but they don't believe the Gandhi incident ever made them unafraid to push forward or take a creative risk. For one thing, they were being punished for a sin — intentional disdain for a beloved national hero — they'd never actually intended to commit. "The only jokes that we ever regret making are the ones that feel kind of mean-spirited," says Miller. "We try not to, like, take people down a peg."

There was another factor too. By that point, their creative symbiosis had become undeniable.

"They work together so well," says Will Forte (Saturday Night Live), who voiced Abe Lincoln on Clone High (and, at the time, was a young comedy writer with zero prior professional acting experience who Lord and Miller had met at the U.S. Comedy Arts Festival in Aspen). "Just when you think you have them figured out, you go, Oh, maybe Phil is kind of the crazy one, and Chris is really so good with the story stuff, and then you go, Oh wait, no no no, Phil's really good with the story, and Chris is the crazy one. And then you just realize, Oh wait, they're really good at both. They are the whole package."

Lord and Miller see it a bit more self-deprecatingly. "It's not like one of us is particularly better with actors, or the other one is particularly good with setting up a shot," says Miller. "We both are mediocre at everything. It's a very inefficient system where we're both involved in every decision."

Lord starts laughing. "We might have stunted each other's growth so much that we'll never get good at anything," he says. "Like a friend said to me, 'The minute I got married, I stopped remembering anyone's name, because my wife was better at that than me, so I just let her be the person in charge of that.'"

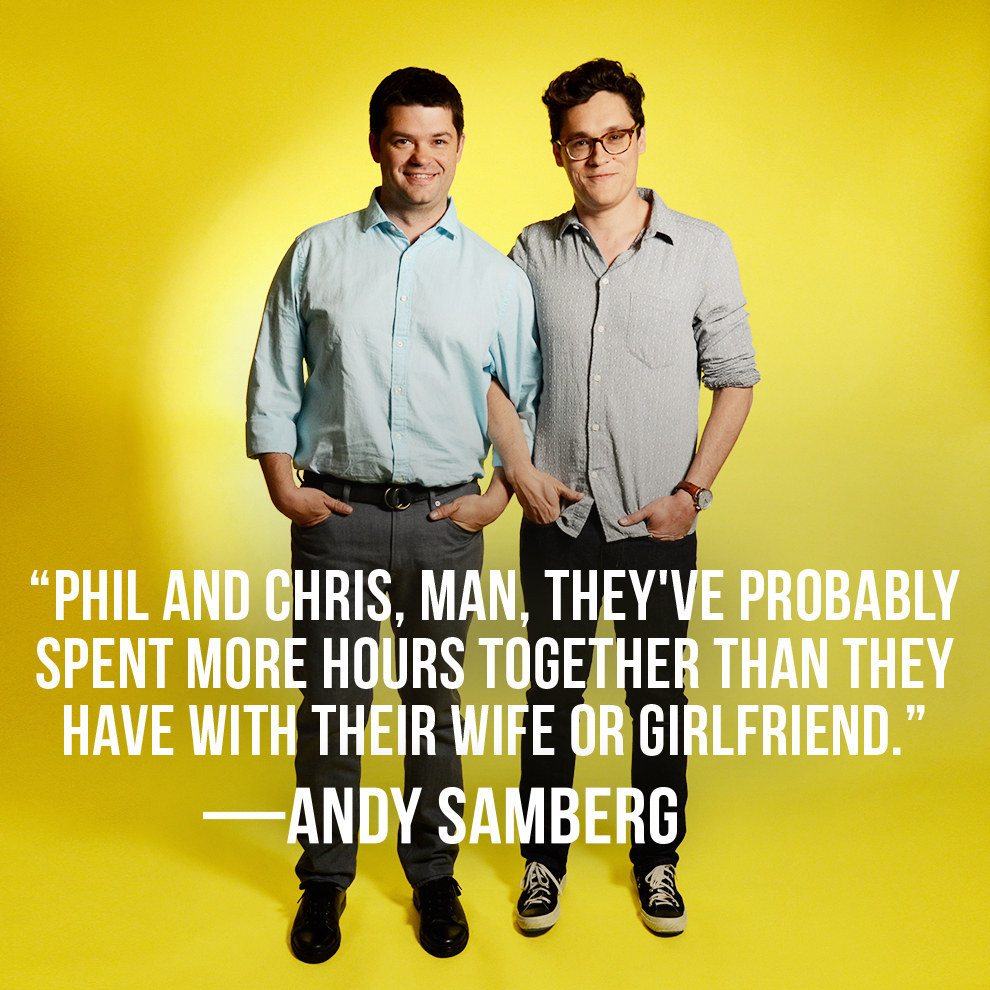

It is difficult to overstate just how invaluable a lasting creative partnership like this — one that is forged within a close friendship — can be in Hollywood. "The fact that they were friends and knew each other before any of the work stuff got involved, I think it's really key," says Andy Samberg, who became fast friends with Lord and Miller after he met them through a mutual friend on the Clone High writing staff. (Samberg did a voice on Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, and Lord and Miller directed the pilot for Samberg's Fox sitcom Brooklyn Nine-Nine.) Samberg formed his comedy group the Lonely Island with his BFFs Akiva Schaffer and Jorma Taccone, and he can see clear parallels between his experiences in his group, and Lord and Miller's relationship.

"Knowing if the work stays or the work goes away, the friendship was first, and I think that gives you a really strong backbone and really helps in communicating with one another and making sure that that's the priority," says Samberg. "Certainly knowing so much about each other — and I know this is the case for Phil and Chris — when you have an idea, you know what they think about the world, and comedy, and movies, and TV. You know [what] they think about everything ever that would be a reference point for what you're working on, and that allows you to interpret whether or not you feel good about your idea." He laughs. "If that makes sense. And all that happens in an eye blink. It's all just embedded in you, because it's the time spent together and the love you have for each other."

After Clone High, as they kept (unsuccessfully) trying to develop new shows on their own, Lord and Miller took a meeting with Sony Pictures Animation, where they caught wind of the nascent animation studio's intention to adapt the cherished children's book Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs into a feature film. Like so many their age, the book had been a touchstone in their childhoods; they immediately talked their way into getting the job of writing it. And after they spent a year and a half on the script, they were fired.

"We wrote what we thought was a super-funny and daring animated script, which it was in some ways," says Lord. They identified with Flint Lockwood, the mad, isolated scientist who invents the machine that creates giant food that falls from the sky — and they decided to make his love interest, the intrepid reporter Sam Sparks, into an amputee. "Sam, like, walked funny for the first two acts of the movie, and then in order to demonstrate to Flint that you have to learn to overcome these struggles — don't be such a baby about it — she, like, took her leg off and said, 'Do you see this?! I don't bitch about this!'" Lord says, momentarily overcome with laughter. "Anyway. They hated that."

There was also a more fundamental problem with what they'd written. "The thing had no heart whatsoever," says Miller. "It was a relentless joke festival with no sincerity at all. The guys who [were] directing it took our script and took out all the jokes, and it exposed the horrible story flaws. The movie didn't work."

Fortuitously, Lord and Miller didn’t have to lick their wounds for long, as they landed gigs writing on the inaugural season of a sitcom that finally matched their sensibility: CBS's How I Met Your Mother. They wrote the show's third episode ever — which helped to establish the go-for-broke playboy personality of Neil Patrick Harris’ Barney Stinson — and relished the opportunity to color well outside the lines of standard sitcom storytelling. And then, out of the blue, Sony called back. The guys who had fired them had themselves been fired, and the studio wanted to know if Lord and Miller would be interested in coming back — this time, to direct. It was an impossible opportunity to turn down, but the timing still really sucked. "We were having a really good experience [on HIMYM], and of course we had to leave," says Miller. "Because everything was going too smoothly."

The first days working their feature directorial debut, by contrast, were bumpy as hell. "We're 30 years old, [and] a bunch of people on our crew are qualified to direct the movie and get passed over," says Lord. "We come into a somewhat hostile situation of guys that are like, 'Who are you?' We'd never really worked in feature animation before. And we make a ton of mistakes right off the bat." So they dipped back into their playbook from Clone High, and opened up the floor to everyone's ideas. "We had no choice but to really sit down and listen to everybody on the crew, what their concerns were for the movie," says Lord. "That really turned the ship around."

They did indeed make some mistakes. "I remember once Phil said, 'Can you get more treble in your voice?'" says Hader of recording the voice for Flint Lockwood. "I was like, 'I don't — I — what?' And then Phil was like, 'Yeah, I don't know what I'm asking. I'm sorry.' And then it was us just apologizing to each other for like, 20 minutes. 'No, no, I can do it. I'm sorry,' and he's like, 'No, no, don't worry about it.'"

Their boss, however, was a bit less forgiving. "It was a long process of basically [Sony Pictures Studio Chief] Amy Pascal yelling at us," says Miller, causing Lord to burst into laughter. Their film had some great new zany bits that worked well on their own, but it still wasn't fusing together as a cohesive emotional experience.

"Amy will say, 'A movie can't be about a person. It has to be about a relationship,'" says Lord, shooting a knowing glance at Miller. "I think that's true." They reshaped their script to become about the strained connection between Flint and his taciturn, widower father (voiced by James Caan) — and it made the movie even funnier. "People actually laughed more because they were engaged in the story," says Miller. "We learned a big lesson on that movie that we try to carry over on everything else we do."

When Cloudy finally debuted in 2009, Lord and Miller's newfound combination of madcap invention and sincere emotion took many by surprise. "I went to Pixar, and the Pixar guys were like, 'How fucking good is Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs?'" says Hader. "Like, 'Those guys did a new thing!'" Producer Neal Moritz says he wanted them to direct 21 Jump Street in part because when he first met with them, they "talked about movies in terms of character and heart before talking about comedy."

Once again, Lord and Miller plunged into the unknown, directing their first live-action movie, and they relied on each other more than ever. "I'll say, 'What do you think about this?' and before they will really give you a firm answer, they'll want to talk to the other one," says Moritz. "They want to be on the same page about it. That's not to say each of them does not have a point of view or perspective, but I think they like to talk it out together and convince each other one way or another."

"I've actually never seen them disagree on set," adds Ice Cube, who plays Tatum and Hill's hard-charging boss in both Jump Street movies. "I found out later that they have all their disagreements in the trailer before they get to set. It's seamless, like a two-headed monster."

That unified front gave Lord and Miller the confidence to push through some unconventional sequences even when everyone around them wasn't sure it was going to work, like a car chase scene in which it seems, like so many other cop movie car chases, that there is about to be a massive explosion — but then there isn’t. "Nobody really believed in it," says Miller. "It was very expensive. We had to shut down a freeway and bridge for several weekends to make it happen. Everyone kept saying, 'Are you sure this is going to work?'" (It did.)

The final act of The LEGO Movie was perhaps their biggest creative and emotional leap (SPOILERS ahead), in which the film's LEGO figurine hero Emmet enters the real world and discovers that the entire film had really been about a battle of wills between a father and his young son. "It was something that we were all nervous about," says Miller. "If it doesn't work, the movie will fall on its face. … We've been lucky enough that people have either been negligent or trust us enough to try weird stuff and have the audience happen to like it."

Both 21 Jump Street and The LEGO Movie were successful — both creatively and commercially — because of convention-tweaking moments like these. “It comes from trying not to be vain about what you're making on the surface,” says Lord. “Like, who cares if it's based on a popular toy brand? It's still an opportunity to make something really interesting. I think we've always approached these things as a way to express ourselves personally, which no one does! Maybe it comes from watching Robert Altman's Popeye a lot.”

As each of their films has been more successful and well-regarded, it has brought Lord and Miller further within the Hollywood fold — they’re part of a "creative consortium" at Warner Bros. Animation along with Nicholas Stoller (Neighbors), John Requa and Glenn Ficarra (Crazy, Stupid, Love), and Jared Stern (Mr. Popper's Penguins). And yet they still aren't quite sure how they get to make movies. "That's how it feels all the time," says Miller. "'Can you believe we're making a movie?!' It's nice to feel like it's your friend [with you], and you're making a movie, and they know it's crazy."

They've known each other now for 20 years, and have been partners for 16. "I mean, Phil and Chris, man, they've probably spent more hours together than they have with their wife or girlfriend," says Samberg with a chuckle. "I mean, those guys have worked together a long time, and long hours."

They'll next shoot the pilot for Will Forte's midseason Fox show Last Man on Earth, which they are also executive producing. But they don't know yet what feature film they will next direct together; The LEGO Movie sequel is in the hands of the first film’s animation co-director Chris McKay. They do know, however, that at some point very soon, Miller will direct The Reunion, a "genre-mixing comedy" he wrote a few years ago — by himself, with Lord producing. It's the first time they will be separated in their professional lives.

"Ssssemmmi-separated," Miller says, looking genuinely nervous to be even considering the idea.

"Well, you're going to be on set, you know, by yourself for a lot of it," says Lord.

"You will be there, hopefully, sometimes!" Miller replies with a nervous laugh, as Lord shakes his head.

This is actually part of their professional plan, that they will occasionally direct a project solo that the other one isn't nearly as passionate about — Lord says he almost did something similar a few years ago. "They'll be like one of those really popular rock bands that stays really tight and all the members occasionally do their own cool solo stuff for fun and then they go back to being the really giant rock band," says Lawrence.

But the separation anxiety between them is also very much real.

"It will be a little bit more like when we were in college, when we doing our own films and helping each other out and giving each other good advice," says Miller, still laughing nervously. "So it will be interesting. We'll see! Might be horrible."

"It will be scary," says Lord. "Right before I almost did something else, I got scared to death. I was like, 'Oh no, now I'm going to be exposed.'"

"But the good thing I know is that, even doing it alone, I can still turn to my buddy and be like, 'Is this crazy? Am I crazy? Is this a good idea?'" says Miller.

"'Come on! Come be there the whole time!'" says Lord, as Miller.

"'It's going to be fun!'" says Miller, as Lord. ●