At first glance, there is nothing in Peter Billingsley's Hollywood office that suggests he's a living pop culture icon. True, there are the framed posters for the films he's worked on as a producer crowding the walls — 2001's Made, 2003's Elf, 2006's The Break-Up, 2008's Four Christmases, and 2009's Couples Retreat (Billingsley's feature directing debut). There are accolades, like the Emmy nomination certificate for the 2001–2004 IFC series Dinner for Five. There are conspicuous tokens of blockbuster success, like the life-size test helmet from the first Iron Man movie, on which he was an executive producer. There's even a valuable artifact of sports memorabilia: a boxing glove signed by Buster Douglas, the man famous for his shocking defeat of world heavyweight champion Mike Tyson in 1990. (Wild West Picture Show Productions, Billingsley's company with actor and longtime friend Vince Vaughn, is currently developing a feature film of Douglas' life story.) But that's all standard movie producer ephemera, similar to dozens of other well-appointed offices of filmmaking types that litter the Los Angeles area.

There is one item, however, tucked into an inconspicuous corner of his office, that makes plain Billingsley is something beyond a prosperous movie industry player. It's a small lamp, with a tasseled shade, and, if you squint, you can make out the important part, the indescribably beautiful part, the part that could remind one of the Fourth of July: a stem in the shape of a woman's leg, wrapped in a cartoonishly suggestive fishnet stocking.

That would be a miniature version of the infamous "leg lamp" from A Christmas Story, one of the most beloved holiday movies of all time. Of course, if you direct your gaze from Billingsley's office to Billingsley's face, one look at his twinkling, ice-blue eyes and youthful, dimpled smile is all you'd need to realize that he is the adult version of A Christmas Story's daydreaming, bespectacled hero, Ralphie Parker. The 42-year-old even still speaks with the slight lisp he had as a 12-year-old in the film. "I guess I've always had a similar-looking face," says Billingsley matter-of-factly. "So I've been told."

Living with his cantankerous old man (Darren McGavin), long-suffering mother (Melinda Dillon), and food-averse younger brother Randy (Ian Petrella) in 1940s Indiana, Ralphie wants nothing more dearly for Christmas than an Official Red Ryder Carbine-Action 200-Shot Range Model BB gun, with a compass in the stock, and a "thing that tells time" — even after his mother, his teacher, and Santa Claus himself all warn him, "You'll shoot your eye out!"

There's really not much more to the plot than that. The film unfolds as a series of nostalgic-yet-clear-eyed vignettes about growing up in this particular family at this particular time during this particular holiday season, adapted from the novel In God We Trust, All Others Pay Cash by Jean Shepherd (who also provides the film's narration as the adult Ralphie).

And yet A Christmas Story has come to embody the holidays so thoroughly that TBS plays it nonstop for the 24 hours between Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. It sits either at the top or very near the top of most lists of the best Christmas movies of all time. "People keep watching it over and over and over and over," says Billingsley. "It just doesn't go away."

The movie has even been adapted into a musical that opened on Broadway in 2012, earning three Tony Award nominations, including Best Musical. (It's currently in a limited run at Madison Square Garden in New York through Dec. 29.)

As the rest of Billingsley's office makes plain, however, unlike many other child stars from the 1980s (or 1990s, or 2000s) — many famous for far less lasting entertainments — he has somehow emerged into adulthood successful and unscathed.

"You know, the transition from a child actor to almost anything is frankly impossible," says Vaughn. "The track record of it is so sadly abysmal. There's usually a lot of tragedy involved." Echoes Jon Favreau, who directed Made, Elf, and Iron Man: "The fact that [Peter] turned out to be, like, a good, normal person, with aspirations, coming out of a life a child star — that's not a given. That's no mean feat."

As Billingsley explains, in the 30 years since A Christmas Story first opened on Nov. 18, 1983, while the film has irrevocably shaped his life, it hasn't consumed it. Quite the opposite, in fact.

"I actually do remember auditioning for it," Billingsley says of A Christmas Story, surprised to even be able to recall it over three decades later.

He had already been working as an actor since he was 2½. He was most well known for a series of commercials for Hershey's syrup playing "Messy Marvin," but he also starred in a couple of big Hollywood movies released in 1981 — Paternity, opposite Burt Reynolds, and a sprawling ensemble comedy called Honky Tonk Freeway that Billingsley refers to this way: "It was like a Terminator 2 budget of its day, I think $21 million, which [was] massive. Bomb. BOMB."

But even though he was a seasoned showbiz veteran by the time he was 11, Billingsley didn't actually live anywhere near Hollywood. For his entire childhood, his parents and four other siblings remained based in Phoenix, Ariz., flying into Los Angeles a handful of times a year to pack in as many auditions as possible. "It is important to me that I was not raised in Los Angeles," he says. "I had brothers and sisters and did chores and had to pick up the dog crap in the yard and mow the lawn and do all the normal things that kids have to do." Billingsley says his mother didn't really even think of acting as a career for her children, all of whom worked at least a little in showbiz — it was more like a hobby that could serve as a kind of time capsule of their childhoods. "This was long before Macaulay Culkin or the Disney [Channel] kids," he says. "My mom knew nothing about it. She thought, They're cute, maybe they'll get a picture for a scrapbook or something to show their kids one day. So when it took off [for me], if anything, my parents were like, 'Jeez, we're sorry. You don't have to do this. This is not what we had anticipated at all.'"

But Billingsley wanted to keep acting, so his parents dutifully kept flying out with him to L.A. for auditions — including one for A Christmas Story's co-writer-director Bob Clark (Porky's, Breaking Point). And when they didn't hear back from Clark for weeks, Billingsley just thought, oh well, he'd lost the role. "Bob Clark said for whatever reason that I was the first kid that he saw," says Billingsley. "But [he] thought, Well, jeez, you can't just hire the first person you see. So my assumption was, 'Well, that didn't go well.' But whatever. You were quickly onto the next thing."

Thousands of kids later, and after an eventual callback, Billingsley did indeed land the film's lead role, and shot the film in Toronto and Cleveland over roughly a month in the dead of winter. "This was a real little grinder kind of indie [film]," he says with affection. "It took [Bob] 12 years to get the movie made. Nobody wanted to fund it, this period movie about a BB gun. Nobody cared about it." With such a tight schedule, and Billingsley in practically every scene of the film, Clark kept his pre-pubescent star hard at work. "It was really cold. And the child labor laws back then, if you didn't live in California, you didn't have reciprocity with the state's laws, and I think Ohio and Canada were very lax. So you worked a lot of hours."

All that concentrated time surrounded by adults forced Billingsley to grow up fast. Take the famous scene where Ralphie says "fudge" in front of his father after spilling the bolts for their car's spare tire. In the film, Ralphie the narrator tells us he actually said "the word, the big one, the queen mother of dirty words, the F-dash-dash-dash word!"

"Oh, they had me say 'fuck,'" he says. "On all the takes. I think we looped in the word 'fudge' on top of it, so you could get the mouth to curl to the consonant of 'K' instead of 'D.' I was like, 'Ohhhhhh, fuuuuuuck!' I had been in Hollywood for a long time at that point; it wasn't the first time I'd heard it, or probably said it."

It's exactly this kind of accelerated adulthood that usually fucks up child actors for the rest of their lives. "When you're number one on the call sheet, you have a lot of power," says Favreau. "You're treated a certain way, and certain things are expected of you beyond what's expected of a kid."

"Well, you grew up faster, I think, in some ways," Billingsley says. "There's a sense of responsibility that maybe other [kids] don't have. But my parents kept that very much in perspective. It was always regarded as a privilege [and] an honor to be a part of this stuff."

Fortunately for Billingsley, when A Christmas Story first opened in theaters, it was far from a hit — even if it didn't feel fortunate at the time. "I remember the only place you could get information on box office was Entertainment Tonight," he says. "I don't know what it did cume, but under $20 [million]." (His memory is spot-on: The film made $19.3 million over its initial theatrical run, roughly $48 million in 2013 dollars.) "And so you think, That's it. This was a 13-channel universe. Movies didn't have a shelf-life, really."

He kept working, shooting guest spots on shows like Who's the Boss, Highway to Heaven, and Punky Brewster, and still landing the occasional lead movie role, like the 1987 Cold War drama Russkies, opposite a young Joaquin Phoenix. (Billingsley's 10-word pitch: "Three kids find a Russian sailor. What do you do?")

But as the '80s crept forward, and VHS sales and movie reruns on basic cable became more central to Hollywood's business model, Billingsley began to notice that more and more people wanted to know about this little Christmas movie he'd done years before. "There was never a flash point or a turning point," he says. "Some local, independent networks would start to run it between Thanksgiving and Christmas. It would pop on, and you think, Oh, that's cool, it's on." During the holidays, Billingsley began noticing VHS copies of the film for sale — and selling well. The film started showing up on those top 10 Christmas movie lists. And then at some point in the early 1990s, he realized basically everyone knew about A Christmas Story, and wanted to talk to him about it. "They would be very complimentary," he says. "'That's my family!' 'That movie means a lot to me!' 'We have a tradition now! Can we take a picture?' Sure!"

The decade-long slow burn, however, meant that Billingsley only really had to start dealing with becoming a famous 12-year-old after he was already in his twenties. "I mean, now you can get famous instantly overnight from some YouTube craziness that you don't want," he says. "A lot of the kids who were my predecessors in sitcoms, you could be nobody, and then Tuesday night at 8 p.m. on NBC, 40 million people watch you, and the next thing you know you can't go anywhere. It just wasn't that. You're not harassed for some weirdness that you did. It was just a very odd, gradual fame. ... For better or worse, it didn't hold me back, and it didn't propel me."

And just as that odd, gradual fame was reaching its apex, Billingsley decided he didn't want to be an actor anymore.

"I thought he was hilarious," says Vince Vaughn of the first time he met Peter Billingsley. They were shooting a 1990 CBS Schoolbreak Special about teenage steroid use called "The Fourth Man," one of Vaughn's very first gigs as a working actor. (The 5-foot-10-inch Billingsley, then 19, was the steroid user; the 6-foot-5-inch Vaughn, then 20 years old, was the friend who warns him to stop.) The two quickly bonded over their shared obsessions for un-hip, non-Hollywood things like country music, Western culture, and video games. "He was like a sweet kid in A Christmas Story and stuff, but he really had a sharp tongue," says Vaughn. "He would kind of make fun of me, which I really liked. I felt that he was very authentic. He right off the bat just let down his guard and joked around."

When filming was over, Vaughn invited Billingsley — who was still living in Arizona at the time — to crash with him in his one-bedroom Los Angeles apartment for a few months. As it happened, Billingsley had been contemplating finally moving to L.A. for the first time, but not to find more on-camera opportunities. "He had started at such a young age and had done it so successfully for so long," says Vaughn. "He really made a conscious effort to stop pursuing that and really pursue being behind the camera."

"It was less of a decision to not act and more a decision to want to do other things," Billingsley says. "It was a great curiosity growing up on sets. One of the things I remember very strongly on Christmas Story is when I would ask Bob [Clark] about lenses or [camera] choices."

As he began to establish himself in L.A., Billingsley discovered that even though he was no longer interested in acting, his most famous role was more present in his life than ever. "We all loved [A Christmas Story], and continue to love it," says Favreau, who met Billingsley in the mid-1990s, as Favreau and Vaughn were working on Swingers. Favreau says Vaughn even introduced Billingsley to him as "the kid from A Christmas Story" — not that he needed to. "Especially when he was younger, it wasn't too hard to figure that one out," says Favreau. "He was never self-conscious about it. As you spend time together, you start asking about details or scenes or moments or just telling them how much you liked [the movie]. And he always was very gracious, not just with us, but with strangers too. He never was resentful of what his past was. I had him sign a Red Ryder BB gun for me."

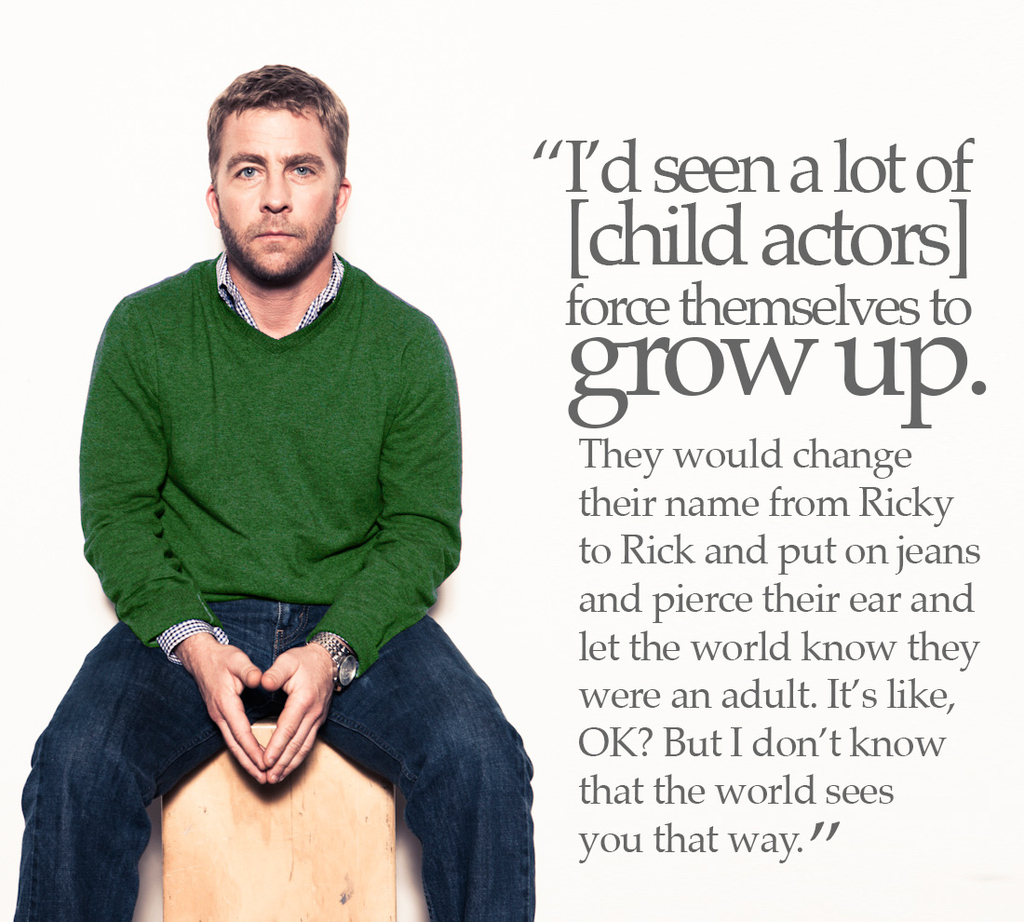

His embrace of A Christmas Story, even as an adult, was also born from a natural aversion to former child stars renouncing their childhoods as fast as possible. "I'd seen a lot of people force themselves to grow up, like at puberty or adulthood," says Billingsley. "They would change their name from Ricky to Rick, or from Bobby to Bob. And they were going to pierce their ear and let the world know they were an adult. It's like, OK? But I don't know that the world sees you that way."

Billingsley's disinterest in forsaking his most successful role as a kid probably also has something to do with his lasting relationship with the man who made that role possible, Bob Clark. "He is hands down the most influential person for my career," he says, "in terms of advising me and always being there to help navigate the roads of going from [being an] actor to [moving] behind the scenes." Clark's biggest advice: Get into the edit room and learn post-production. "He said it's the best place to learn film, and he was not wrong," says Billingsley. "He said, 'You've spent a lot of time on sets. You understand the flow of production a lot. Start [in the edit room] and then work out.'" He pauses. "I didn't have much warmth from others that I had reached out to, filmmakers in the past. I don't know why. But they were not enormously helpful in terms of advice." (Clark died in a car crash in 2007.)

So rather than indulge in the easygoing lifestyle of an underemployed famous twentysomething in Los Angeles, Billingsley did the same thing he'd done his entire life: He worked. "He was very disciplined," says Vaughn. "He would make himself work during the day, even if he had nothing to work on. Whether it was 8 to 5 or 9 to 5, he would stay in my place and treat it like a job, write stuff and develop stuff. He would not hang out. This went on for years."

Vaughn was so impressed with Billingsley's work ethic that when he and Favreau collaborated again for their 2001 indie mob comedy Made, he suggested Billingsley come on board as a co-producer — not as a favor for a friend, but as a guy who was going to get shit done. "We needed an airplane to shoot in, but we didn't have the money," says Vaughn. "Peter made a crazy deal with the airplane company to set that up. A lot of people don't have an understanding of all sides. Peter can tell you how it's working financially, he can technically tell you about the camera. He can tell you about special effects and how they work and what they do, how you go about it. He also has really good taste. He has all those assets."

After Made, Billingsley regularly collaborated with Favreau and Vaughn. He produced Favreau's IFC talk show Dinner for Five, co-produced Favreau's 2005 film Zathura, and executive produced on 2008's Iron Man. Favreau even coaxed Billingsley back in front of the camera in a cameo as one of Santa's elves in his own Christmas movie, 2003's Elf. "I think it's subconscious and subliminal, but he's bringing a certain Christmas pedigree, a Christmas magic," says Favreau, totally serious. "I was very lucky to have him do that for me."

With Vaughn, Billingsley formed Wild West Picture Show Productions, named after the comedy road show Billingsley and Vaughn launched in September 2005 and captured in the feature documentary Wild West Comedy Show: 30 Days & 30 Nights — Hollywood to the Heartland. (In the film, the duo even re-create their confrontation from that fateful after-school special.) Billingsley executive produced Vaughn's films The Break-Up and Four Christmases, as well as Wild West's TBS sitcom Sullivan & Son, currently in its third season. And this year, Billingsley also collaborated with Glenn Beck's independent network The Blaze on a reality competition TV series called Pursuit of the Truth , in which prospective documentary filmmakers vie for a chance, Project Runway style, to make their film. (Billingsley is also a judge on the show, and shot a get-out-the-vote PSA for The Blaze in which he exhorted the value of individual freedom over the government, but he says Pursuit of the Truth's politics are "100% down the middle.")

He speaks now with a practiced-filmmaker patois, like when discussing his next film as director, Term Life, which begins shooting with Vaughn, Hailee Steinfeld, and Bill Paxton in March. "It's an action sort-of thriller with a bit of levity, but more like the tone of Iron Man," he says. "It's really a father-daughter story. We sort of call it 'Paper Moon wrapped in an action package.'" Billingsley has spent so much time working behind the camera, in fact, that Vaughn takes issue with the notion that anyone could still see him only as the kid from A Christmas Story. "I think if you were dealing with someone who that was the one thing that they did, that would be one thing," he says. "[But] I just think you'd have to live in a bubble to not know what Iron Man was, or The Break-Up, or Dinner for Five. I mean, I don't even think it's a conversation."

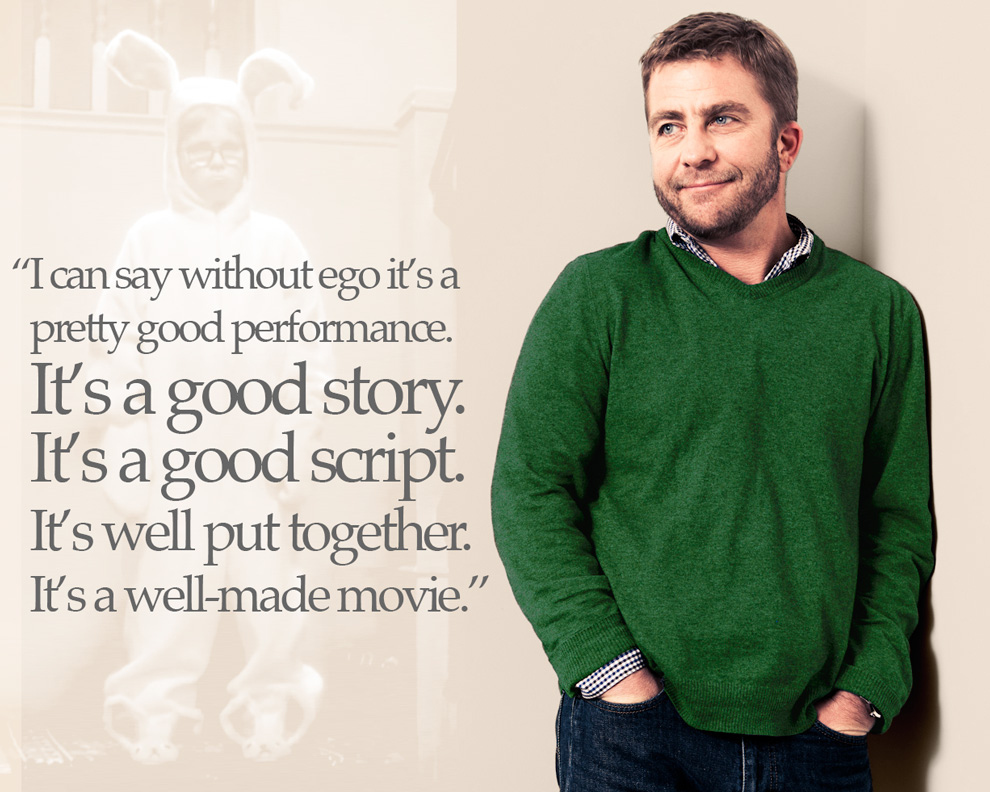

It is, however, a conversation that Billingsley himself is still happy to have. "It took me a while to appreciate it as a film," he says. "But I watch it now and go, you know what, that's a damn good director. I can say without ego it's a pretty good performance. It's a good story. It's a good script. It's a well-made movie." After 30 years, perhaps more than anyone on the planet, Billingsley has an intimate appreciation of why the film has resonated with audiences so deeply — and why it took Clark 12 years to get the film made.

"Try selling that [film] today," he says. "I mean, tell me the set-piece comedy scenes? Well, let's see. He tries to make a turkey. They go pick up a Christmas tree. The dad gets a delivery. It doesn't leap off the page. But quite frankly, I think its genius is its commitment to the mundane — it was almost like early Seinfeld. You're just trying to get your kid to school. You're just trying to avoid a bully. You're just trying to stay warm and put on a suit. It's very familiar things, but you take those and make them really big moments."

His innate understanding of A Christmas Story's strengths led Billingsley to spark to a stage musical version of the show and bring it to Broadway — the first time, outside a DVD commentary with Clark, that he's ever attached his name to anything having to do with the movie. "[It was] a little bit of a lightbulb moment," he says of the day in 2009 when theatrical producers Gerald Goehring and Michael F. Mitri approached him about producing with them to help improve a version of the musical that had been playing in Kansas City, Mo. "Like, oooh, I can really see that. Dad wins a leg lamp, and it turns into a leg-lamp kick line. It's all there. He's making it like it's really bigger than it is, because he needs that to feel good about himself."

What has been perhaps the most satisfying experience of all for Billingsley is that for the first time, other kids get to know what it's like to be Ralphie, Flick, Schwartz, and Randy, while he gets to sit in the dark with the audience and watch the story unfold from afar. "Every night I watch the show live, I get a good little butterfly in my stomach," he says. "It has a wonderful reminder of a lot of history. It's great to hear audiences roar and stand up and love it." ●