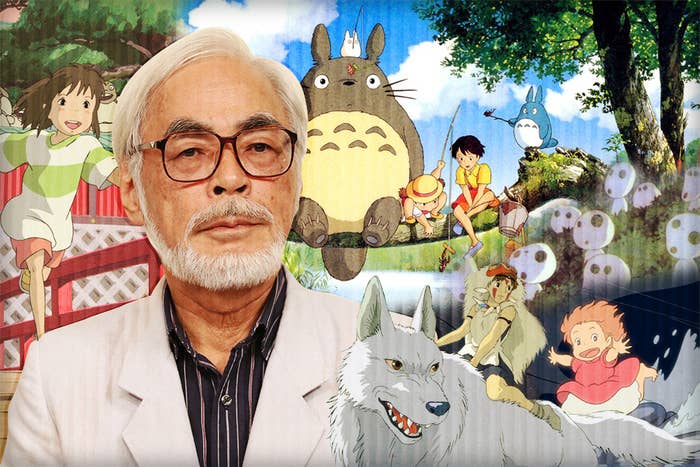

When The Simpsons paid tribute to animation legend Hayao Miyazaki in January, the video quickly went viral, becoming the third most viewed Simpsons clip on YouTube ever, with nearly 10 million views.

Miyazaki, however, was not one of them.

"Unfortunately, I haven't seen that," the 73-year-old filmmaker told BuzzFeed earlier this month, in a video call conducted with a Japanese translator. "Actually, I don't watch that much TV," he added with a laugh. "I don't know how to use the internet, as well. Someone gave me an electronic dictionary, and I'm just trying to find out how to use it right now."

Anyone familiar with Miyazaki's astonishing body of work will recognize in that answer one of the central themes of his films: the tension between a simpler way of life — where one looks up words in old fashioned dictionaries — and the relentless drive of technological progress. That theme is malevolently present in Miyazaki's medieval fantasy Princess Mononoke, the first of his films that most Americans saw in a movie theater when it opened in a limited release in 1999. That theme is woven into the fanciful world of Spirited Away, which won an Academy Award in 2002 for Best Animated Feature Film, and is the highest grossing film of all time in Japan. And that theme is even front and center in one of Miyazaki's earliest features, 1984's Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, an adaptation of one of his popular manga comic books.

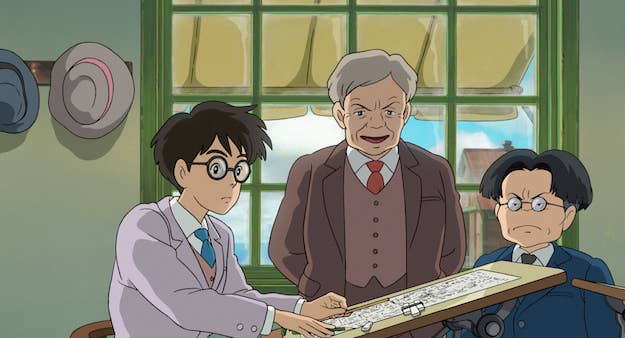

It is a theme that is most heartbreakingly present in Miyazaki's latest feature animated film, The Wind Rises — which, he announced last fall, is also his last. A historical epic based largely on the life of Jiro Horikoshi, the aeronautical engineering genius behind Japan's deadly Zero fighter plane in World War II, the film's elegiac tone certainly makes for a fitting culmination to Miyazaki's 50-year career. (The film, nominated for an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature Film, opens in the U.S. today in limited release, with an English-language dub featuring Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Emily Blunt, John Krasinski, Martin Short, Stanley Tucci, Mae Whitman, and Mandy Patinkin.) It wasn't until Miyazaki had completed the film, however, that he says he realized he would retire from feature filmmaking.

"I really felt that this was the maximum that I could give to produce an animated film," he said. "The work of animation is building up bricks and mortar, bricks and mortar. I felt I wouldn't be able to put [up] another brick."

Miyazaki has announced his retirement before, only to return to his animation company Studio Ghibli to make another feature (or three). But this time, his resolve feels permanent. And with so much of today's feature animation created using the cutting-edge perfection of computers, it's impossible not to wonder who, if anyone, will take pencil to paper to create animated films with as much bewitching — and popular — imagination. Ironically, it's exactly Miyazaki's singular devotion to his craft that has led him to leave it behind.

Spirited Away and Ponyo

While none of his films have grossed more than $15 million in the U.S., Miyazaki has nonetheless earned a devoted American following, no more so than in the world of animation. "In the early days of Pixar," said Toy Story 3 director Lee Unkrich in a phone interview, "John [Lasseter] would often show Miyazaki's films, and [he was] always very excited about them. His films are absolutely gorgeous, especially the backgrounds. I could just pause his films and just spend time drinking in the beauty of the paintings he uses for his backgrounds on any given scene."

The Simpsons executive producer Al Jean said his team had been trying to work in an homage to Miyazaki on their show for at least a decade, but the eventual episode — in which Comic Book Guy marries a woman from Japan — was well underway before the filmmaker announced his retirement. "The character design is wonderful," Jean told BuzzFeed. "Character design is, to me, one of the hardest things about animation. You have these characters that combine animals or spirits with human qualities, and in a way that's really seamless. You don't think it's a ridiculous-looking being. You think it's just a really perfectly looking creature. He does it again and again and again. It's rooted in anime traditions, but it's still like nothing else."

That appreciation for detail extended beyond his feature films too. Unkrich recalled watching one of the short films Miyazaki made for Studio Ghibli's museum in suburban Tokyo. "There was a character, a little girl, sitting in a field, unwrapping a piece of candy," said Unkrich. "He goes in on this close-up of the hands, holding the piece of candy that's kind of coveted and very important to this little girl. And she just slowly opens the wrapper, very meticulously. He spends so much screen time on this that part of my brain is just blowing up, thinking, My god, how can he get away with just focusing on this one little detail? But at the end of the day, it's just this wonderfully, beautifully observed moment. His films are just filled with moments like that."

Getting that level of thoughtful precision, however, demanded Miyazaki maintain a painstaking, time-consuming daily schedule. He rises at 6 a.m. each morning for exercise and coffee, and arrives at Studio Ghibli by 9 a.m. — often working Saturdays and holidays, too. "I usually postpone the lunch break, because when you eat lunch, you get sleepy and tired," Miyazaki explained. "I eat at around 3 p.m., and then I take a break. And I have a promise with my wife to leave the studio at 9 p.m."

Miyazaki needs all that time because he draws his film's initial storyboards entirely himself, entirely by hand, an unheard of workload for an animated feature, which is usually a highly collaborative creative endeavor. "He's probably the only auteur working in animation," said Unkrich. "Every frame of those films are the way they are because he wanted them that way." That's not just a platitude. After passing along his storyboards to his animation team so they can flesh them out into fully animated sequences, Miyazaki reviews their work, and if he can't communicate his changes verbally, "I re-draw their drawing," he said.

Princess Mononoke and Kiki's Delivery Service

With The Wind Rises, Miyazaki chose to complicate his process even further by adopting a realistic aesthetic, similar more to a live-action film than the whimsical fantasias of his previous features. While Miyazaki had toyed with doing a film this way in the past, he said his longtime producing partner Toshio Suzuki finally convinced him to actually go through with it. "I told him that if we create such a film, that would be like digging the tomb of Studio Ghibli," said Miyazaki. "We were starting to create something that was the opposite of what we had been creating." He laughed. "There were a couple of animators working for me through the production who mentioned they don't understanding what they're creating. Of course, they didn't tell that to me directly, but I knew what they were thinking by seeing them working." (Miyazaki later noted with a laugh — he laughed a great deal — that he's been told by several people who had seen The Wind Rises that he resembles the character of Mr. Kurokawa, the hard-charging director of an aeronautical engineering firm who marches past the desks of his firm's designers and engineers, barking out orders.)

As their work literally piled up, stacked sometimes past the heads of his animators, Miyazaki and his team fell so behind that he was unable to personally review each and every drawing. "I didn't have enough energy to correct everything," he said. "When I look at the movie, and I see those scenes, I try to look at the corner so I don't look at anything. Of course, I know how to correct those scenes, but we don't have enough time and energy. There are a lot of directors who don't even look at those drawings, don't correct them. But, of course, I am an animator. I can only express myself by drawing."

Miyazaki is not the only filmmaker making feature animated films at Studio Ghibli. The Secret World of Arrietty, written and produced by Miyazaki, and directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi, opened in the U.S. in 2012 and actually grossed more ($19.2 million) than any of Miyazaki's films have in North America to date. But much of that audience would likely have never flocked to the film had Miyazaki's name not been on it. And with the rest of the world of feature animation so deeply invested in 3D computer architecture — and often pulling in near-billion-dollar grosses as a result — it's hard not to wonder how much longer Miyazaki's 2D, hand-drawn process can last. The last major 2D animated feature release in the U.S., Disney's The Princess and the Frog, was seen as a financial failure. "People like to blame box office success or failure on the medium rather than any number of other factors that go into it," said Unkrich. "So there's not a lot of financial incentive now for big studios to do hand-drawn animation. A lot of them see it as old fashioned and not current. Of course, we all know it's just as beautiful and deserving of being in the world as anything that we're doing [at Pixar]."

As he was in the middle of making Toy Story 3, in fact, Unkrich found himself unwittingly sitting in the middle of the collision between Miyazaki's small 2D animated world and the much larger world of 3D animation. In an early draft of the script, screenwriter Michael Arndt tossed in a reference to the young character of Bonnie owning a plush version of Totoro, the title character from Miyazaki's 1988 film My Neighbor Totoro (which didn't reach most U.S. audiences until the mid-2000s). "He didn't do it with any ulterior motive in mind," said Unkrich. "He just needed to write something on the page. But we ran with it, just for fun, thinking we'll never be able to do this. We started storyboarding one of the characters being a Totoro. And he was in the reels. John [Lasseter] was delighted to see him there. And at a certain point, we thought, well, why don't we do this?" Miraculously, Studio Ghibli granted Pixar the rights to the character — Lasseter's close friendship with Miyazaki likely didn't hurt — but the final OK did not come until Miyazaki himself happened to pay a visit to Pixar's studios in Emeryville, Calif., while Toy Story 3 was still in production.

"It was the first time, I think, he was ever seeing one of his characters rendered in 3D," said Unkrich. "We made it very clear that we weren't trying to animate Totoro the character, but we were animating a plush figure of Totoro — there was a distinction between the two. He was sitting right next to me as I showed it to him. There was long pause, and he just kind of gave an ever-so-slight nod and just went, 'Humph.' And that was it. That was his tacit approval that we could put Totoro in the film. That was kind of the end of it."

My Neighbor Totoro and Toy Story 3

When he was asked for his opinion on 3D computer animation as an art form today, Miyazaki just chuckled, and chose to sidestep the question. "Well, personally, I like more 2D animation," he said. "For cars, I love manual transmission. That's the difference, I believe. Of course, right now you have a lot of options for creating an animated film. When I see people working on computers creating animation, it's watching something magical happening. But I turn back every time to my pencil and paper. That's only how I can explain it to you."

But Miyazaki was clearly also not keen on writing the epitaph of his chosen profession. "I think it's not really necessary to predict what will happen in the future," he said. "If someone comes up and he is talented and wants to use a certain medium, he will go in that way and that will continue that style. Commercially speaking, animation films have always been facing challenges and difficulties. But I was very lucky for my 50 years in my career; things in the animation market went very well, so I had some space to work. But of course, there are lots of predecessors who worked in the same medium when things were more difficult commercially. So I still believe someone will continue 2D drawing — even if commercially, it doesn't go well. It just needs someone with a strong will to continue this medium."

This is a man that has spent the majority of his life with his eyes fixed on sheets of paper just inches from his nose, as he brings to life phantasmagorical stories that seem to touch upon an elemental yearning in his audience. "He can come off pessimistic and cynical about modern society," said Unkrich. "I think he's trying to chase a kind of purity, and a way of life and another time, when things maybe weren't so hectic and commercial."

Now that he's not facing the grind of directing a feature film, Miyazaki may be able to find that way of life again. He says he'll keep working on "exhibition projects and short films" for the Ghibli Museum, but his real hope is to get back to drawing a manga comic — just him, his pencil, and a single sheet of paper, "without thinking of the cost for production. That's a perk for me as an old man right now."