Adam B. Vary: Here we are, Jaimie, two people who have seen — and have had quite different reactions to — Gone Girl. In our first meeting about the movie, in fact, one of us may have been moved to speak at quite an elevated volume about the other's opinion about the film. Which, for the record, I think is pretty exciting — it is all too rare anymore that a movie can evoke this kind of raw feeling! And I do think that is something director David Fincher and novelist-turned-screenwriter Gillian Flynn have engineered Gone Girl to do from the very first shot. (I should acknowledge here that Flynn and I both worked at Entertainment Weekly at the same time for a few years, and we were friendly with each other, though I haven't seen or spoken with her since her book tour for her second novel, Dark Places.)

When Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) looks down at the blonde head of his wife, Amy, (Rosamund Pike) resting on his chest and wonders in voice-over what it would be like to crack open her skull to discover what she is thinking, it is at once a horrifying and, I feel, searingly honest sentiment. I think most every person in a relationship has had similar (if perhaps tamer) thoughts pop into their head in the heat of the moment about their loved one. Where those thoughts lead Nick and Amy, however — and what their behavior reveals about how we feel about men and women and how they relate to each other, in private and in our culture at large — is how I think Fincher and Flynn did mean to cause such heated debate among, for example, colleagues who are otherwise good friends.

Jaimie Etkin: Well, seeing as Gone Girl has made me angrier than any movie I've seen in recent history, I guess they were successful in that regard. I think the most important dialogue the movie inspires is something you alluded to in saying it examines "how we feel about men and women and how they relate to each other." Nick's violent prose about wanting to unspool Amy's brains is perhaps the most violent thing he says in the whole film (though not the most violent thing he does), and it seems to be motivated by the fact that he cannot understand his wife in a Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus sort of way. That voice-over sets the tone to me that Nick's motivation is pure, even if his outward appearance (smashing glasses in front of detectives, smiling in front a poster of his missing wife for the media, etc.) says otherwise — it says that he is the one trying and Amy, with her bitterly cold glare, is the frosty bitch who won't let him in.

Besides, after that scene, the camera, which had shown said glare through Nick's eyes, moved away from his first-person perspective to an omniscient, non-voice-over one, which to me, showed the filmmaker's partiality to Nick's side of the story. We never get to see the story from his perspective again and instead, it appeared to me that what we see of Nick from there on out is the but-this-is-what-really-happened version of the story.

ABV: I think this is where our reactions differ the most, because to me, this movie is pitting two different nightmare cultural archetypes against each other — the crazy psycho bitch, and the selfish, shiftless loser — and it doesn't really care which one "wins." It just enjoys watching the (metaphorical and literal) blood flow.

I agree that Fincher and Flynn split the film's perspective on Amy and Nick in quite different ways. For the first half of the film, Nick gets the benefit of an omniscient, present tense point of view, while Amy's perspective is one of a subjective — and quite unreliable — narrator. And to me, that is tied up entirely in how we so often experience male and female perspectives in our culture. The man gets to be the audience's proxy, while the woman's perspective is held at a remove. As it plays out in Gone Girl, it's unsettling — to me, in a satisfying way — until it's shattered in the film's second half.

Before we get tangled up in what happens to Amy, though, I wanted to follow up on something you said about Nick. Because I feel like there's a big difference between him smiling in front of that poster — i.e., him trying (and failing) to "perform" being a good guy for the cameras — and his private explosions of violence in front of Det. Boney (Kim Dickens), which felt much more revealing of Nick's darker, truer self, and where the film's omniscience shifts its weight to how Boney sees Nick.

JE: Certainly, Boney serves as the viewpoint of the audience toward the end of the first half of the film, but — and this is probably the perfect time to note that I am one of the four adult humans who did not read Gone Girl and knew nothing of the twist before seeing the film (greetings from underneath this big-ass rock of mine) — as soon as I felt like maaaaybe Nick did kill Amy, we faded in on an alive and not-so-well Amy in her headscarf, cruising down the Cool Girl highway with a Kit-Kat at the ready. At that point, Nick becomes guiltless in viewers' minds and the rest of the film centers on Amy validating every straight man's fear (the notion that "bitches be crazy," as our colleague Jace Lacob said after we saw the movie), while the audience waits for Nick to find a way to get Boney and the world to see that he was innocent the whole time.

So, not only do I disagree with you that the film doesn't really care who wins, but I find it quite insane that you see Gone Girl as a pitting of "two different nightmare cultural archetypes: the crazy psycho bitch, and the selfish, shiftless loser." Nick is a cheater who doesn't want kids, and who may or may not have pushed his wife into a banister, but he goes down on his wife, he cares for their cat, he loves his sister so much and would do anything to save her, he moves to be close to his sick mother, and he wants to protect the pretty young thing he's in love with. Amy is a woman who — again, as is every straight man's nightmare — wrongly accused a man of rape and ruined his life in the process, stole a neighbor's urine to fake a pregnancy, manipulated and murdered a man not in self-defense (and lied again about being raped), faked her death in order to get her husband the death penalty, and I could go on. As opposed to Nick, Amy's most human moment was hearing how a poor little rich girl was sort of, kind of, not really used for the sake of her parents' children's books. (OK, fine, and maybe her love of Kit-Kats.) The level of nightmare is just so disparate, I don't see how you can possibly compare the two.

ABV: I am comparing them because I think the movie put them up on display for me to compare them, but I also don't think they are supposed to be seen as equal nightmares. As our colleague Kate Aurthur pointed out when we were all discussing Gone Girl, in the second half of the film, Amy exists in a completely different movie. She's not in Nick's realistic crime thriller, she's in an almost operatic revenge fantasy that escalates into bigger and bigger levels of insanity up to the completely insane climax with her quasi-savior, quasi-captor Desi (Neil Patrick Harris). Amy is absolutely a men's rights activist's nightmare, and I don't think we are ever meant to really sympathize with her. (This is something I do miss from the book, by the way; Flynn's prose gives us a far more complex and thorough picture of what led to Amy's pathology than the film ever attempts.)

But, to be clear, I am baffled that people are sympathizing at all with Nick. From start to finish, I found him to be loathsome, selfish, and miles away from "guiltless." Beyond the cheating, lying, and his flashes of genuine, destructive violence — up to and including him actually slamming Amy against a wall after she's revealed she is pregnant with his child — he lies to his twin sister Margo (Carrie Coon) and uses her as an emotional crutch while grousing about being "judged by women." And much like we never really understand what made Amy so insane, we're given even less of a sense of whatever bond Nick had with his sick mother — and he moves Amy back to his home at least in part because they lose their jobs and cannot afford to live in New York anymore. We are, on the other hand, given a very clear picture of how important it is to Nick that other people think he is a "good guy," much like Amy's false construction of the "Cool Girl." Nick's construction, however, is not for the benefit of others; it's for himself. And I personally felt like the movie saw through it.

JE: Adam, you just said it right there yourself! While you may not think Amy and Nick are equal versions of nightmares, the movie puts them on display for you to compare them. Which is a huge fucking problem! When you look at that aforementioned list of Amy's behavior next to Nick's, which, as you point out, you are almost asked to do, it is clear who is the worse human being and thusly, why wouldn't the viewer sympathize with Nick or want him to win? And therein lies my main problem with this incredibly sexist movie that gets more sexist in my not-yet unspooled brain the more I think about it.

ABV: So much to respond to there! First, it feels almost like a trap for me, a cis white man, to say this movie isn't sexist, but I don't think it is. Boney and Margo are easily the two best human beings in the movie — the ones with the most profound feeling of well-placed moral outrage. If the movie really did have no real regard for women or think them unimportant to the storytelling, I don't think it would have made the emotional and psychological room for these two characters to be as present in the movie as they are. If I sympathized with anyone in the film, it was with them.

Second: I don't think we have to sympathize with Nick just because Amy is such a psychopath. It's a fascinating bind the movie puts us into, leading us to think Amy is the victim, and then Nick is the victim, when I strongly believe we're left with the pitch-black conclusion that neither of them are. If Amy becomes an over-the-top monster, Nick reveals himself to be a self-interested slimeball.

JE: I could not agree more that Margo and Boney are two of the best human beings in the movie, particularly Go. But that doesn't mean I don't also feel like they are treated unfairly as women (and let's not lie, Fincher doesn't have the best track record here). And I don't think it's a coincidence that Go and Boney are two of the most desexualized characters in the film.

Go believes in the good of Nick more than anything (besides barrettes, maybe), and we're led to believe Boney thinks all men are assholes after the divorce she brings up often. She's just looking for the worst in Nick, who, what do you know, didn't kill his wife and proved her wrong. Both Go and Boney only exist in the context of Nick and more specifically, they exist to make the audience believe Nick is a good guy.

And do you think it's a coincidence that the two cable-TV hosts (played fantastically by Sela Ward and Missi Pyle) whom Nick is trying to win over, after they put words in his mouth and dig into his past solely for the sake of a story, are women?

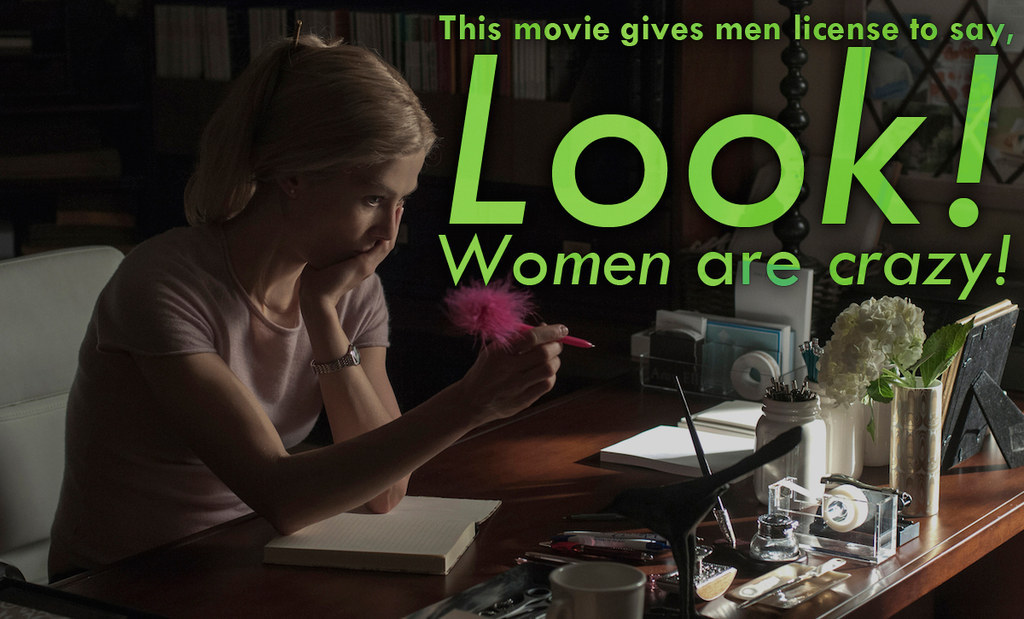

You say we don't have to sympathize with Nick just because Amy is such a psychopath. But the ways in which Amy displays her psychosis (and she truly is a psychopath, which is another issue in the movie's treatment, or lack thereof, of mental illness) are clichéd and thusly, sexist in and of themselves! Lying about rape not once, but twice (one time of which was to defend a murder)? Faking a pregnancy in an incredibly calculated way to manipulate her spouse? I mean, the only thing that's not sexist about that was that it implies Amy knew how to fix a toilet. These are caricatures of straight men's biggest fears about women and this movie gives men license to say, Look! Women are crazy! The women in this movie are either one-dimensional crazies (Amy), asexual lackeys (Go), out-to-getcha, man-hating snakes (Boney), boobs on a stick who will stab you in the back (Andie), less-revealing boobs on a stick who will stab you in the back (the woman who took the selfie)... I mean, the list goes on and on!

ABV: Whoa, I think you're being pretty harsh about Go and Boney! (For one, it is rare for most supporting characters, male or female, to have a clear sexuality in a feature film; for another, I don't think Boney hates men!) But I do think you've helped to bolster my point that the movie fixates on the idea of Nick as a "good guy," only to slowly chip away at that notion and expose Nick as anything but a "good guy" by the end.

Speaking of guys, let's not forget there are several unlikable — or at the very least, one-dimensional — men in this movie too. There is Boney's judgmental partner Jim (Patrick Fugit), who barely exists other than to express his immediate dislike of Nick. There is Amy's father, Rand (David Clennon), who we know "plagiarized" Amy's childhood, and who also exists solely as a proxy for how the larger world begins to turn on Nick. There's Jeff (Boyd Holbrook), the tattooed jerk who violently robs Amy only after Greta convinces him to do it.

And then there is Desi, a vain one percenter who "rescues" Amy but only wants her to be his crowning ornamentation within his opulent lakeside hideaway. I think we are supposed to find him creepy and controlling and even threatening — a different kind of male nightmare. But I should note that in the book, Desi is even more sinister; he really does trap Amy at that house, making her ultimate decision to kill him less of an overt choice on Amy's part. But the even bigger difference is just how much Fincher revels in the Grand Guignol melodrama of Desi's murder itself — and where I think any notion of Amy as a "realistic" character is drowned in a gushing river of blood.

JE: In an effort to avoid thinking about the copious amounts of blood in that scene, let's talk about these other men you speak of. They may be one dimensional — and interesting that you mention Jeff, who is manipulated by a woman into doing something terrible to another woman, who is also terrible, so, who cares, because, bitches be not just crazy, but also awful — but they don't all exist to make Amy look better. Unlike that long aforementioned list of women who are essentially present to do that for Nick's sake.

Part of the issue is it'd be impossible for anyone to make Amy look better by the time her master plan is revealed and she is painted as a total and complete psychopath, increasingly so, as the film draws to its conclusion. Particularly after the Desi scene. I know fans of the book were perhaps most dubious of Neil Patrick Harris' casting. And I do think that Desi didn't come across as sinister as he needed to be in order to validate Amy's actions in the film, again unfortunately feeding into the bitches-be-crazy trope that frustratingly permeated those two hours and 35 minutes for me.

It's so interesting to me that you feel like the movie slowly chips away at the notion that Nick is a "good guy," whereas I felt like it went the opposite way. The Nick I root for the least is the one who robotically moves around his McMansion as the number of minutes he hasn't heard from his wife climb. And the one I root for the most is the one who sits on the couch next to the woman who essentially ruined his life at the end of the movie. Truly, it took a lot for me to not root for Nick when he smashed Amy's head against the wall and called her a cunt. And that behavior is absolutely abhorrent and inexcusable! But the way the story had unevenly played out up until that point, it felt like I was supposed to think Amy deserved that. (Note: No woman ever does.)

ABV: Being "less awful" than a psychopath is a terrible endorsement for a human being! I am genuinely concerned that you rooted for Nick at all by the end!

JE: For the record, I AM TOO! That is my point!

ABV: Well, I am relieved to hear that. But I just have to return to what seems like our fundamentally different reading of the film. I agree that Amy's psychopathic behavior embraces the tropes of the psycho bitch, but I think that is the point. Amy has lived her life as the projection of other people's expectations of her — Amazing Amy as a child, the "Cool Girl" as a wife, the wronged pregnant victim as a media darling, and the diabolical psychopath as the star of a David Fincher thriller. The movie is playing with how we can never totally know anyone, especially a significant other, and yet how we constantly project our judgments and expectations onto loved ones, strangers, celebrities, even fictional characters. Nick withers under that spotlight, grousing about how everyone is "projecting their shit" onto him — much the same way that some men are not exactly keen on recognizing the ways they can be destructive assholes. But it is something Amy has learned to use to her advantage by "playing" those roles to the hilt.

It's weird and meta, and I loved how it fucked with me. I think there should be room for a female character in a movie to be this elaborately insane. Besides, I may be in the minority on this, but by the end, I actually kind of liked Amy more than Nick, in that I thought at least by the end Amy was totally honest about who she was and what she wanted. Nick, by contrast, was still trying to fool himself into thinking he was a "good guy," even as those around him — especially Go, who is so devastated to realize that her brother wants to stay with Amy — know otherwise. After he slammed Amy against that wall, there should be no doubt that Nick is not a good guy. By the end, if I'm being truly honest with myself, I kind of wanted to see Amy succeed in ruining him.

JE: There's a lot I could continue to disagree with you on there, but I think we'd just be chasing each other on some sort of Fincherian hamster wheel and I am tired. While I agree with you that there should be room for a female character to be insane on screen, that character comes across completely differently when her insanity isn't treated as a mental illness and therefore, is presented as her being just another "crazy fucking bitch," as Nick calls her in the movie. But this issue might call for another post entirely.

ABV: Well, as I said at the start, I think we are totally supposed to be having this argument. Fincher and Flynn are savvy storytellers, and they have crafted a movie that leaves itself open to a wide number of interpretations and responses. This is a good thing, and a rare thing, and I celebrate it!

Besides, at least we can agree that Tyler Perry — as Nick's constantly bemused lawyer Tanner Bolt — was, shockingly, our favorite part of the movie. Er… right?

JE: Well, Carrie Coon was my favorite part. But Tyler Perry was a pleasant surprise, for sure. I just sighed aloud, Adam. A day in which we have to relegate ourselves to agreeing on Tyler Perry is not a day I'd call a success.