About 20 minutes into the first of three phone interviews with actor-producer-director Bob Balaban — I was in sunny Los Angeles, he was in wintry New York City — he stopped in the middle of an answer about acting as the head of NBC in several episodes of Seinfeld.

"Oh my god," he said. "Everybody's OK, but a giant block of ice just fell 20 feet from where I'm standing, outside the restaurant where I'm going to have lunch. Oh my god, right in front of the door where I would've been walking in. It destroyed the neon sign above the doorway to the restaurant, and it exactly crashed on where I would have entered the door. I could have been killed during our interview!"

For a character actor who has spent his nearly 50-year career playing quiet, circumspect men, Balaban's life is full of flashpoints of excitement. He's worked with everyone from Steven Spielberg to Lena Dunham and George Clooney to Robert Altman. He's appeared in two Woody Allen films — one before the Mia Farrow scandal broke in 1992, and one after — and his performances in two other Allen films ended up on the cutting room floor. He's appeared on memorable episodes of Friends and The West Wing, directed Philip Seymour Hoffman in one of his first feature film roles, and was a regular fixture in Christopher Guest's quartet of sublime improvised comedies.

And this week, he'll appear in The Grand Budapest Hotel, his second film with director Wes Anderson.

"He's always his own self in all situations, and it's a delightful self, and very practical self," Balaban said of Anderson. "You think he might be eccentric, and he wears a suit all the time — that's considered eccentric. But he's not at all eccentric. He's practical. He knows how to get what he wants in a very pleasant way."

Balaban's ease with show business seems to come naturally — his uncle Barney Balaban ran Paramount Pictures for 30 years — but Balaban said that while growing up in Chicago, he was barely aware of his family's powerful position in Hollywood. "There was no show business at all practically speaking in my family," he said. "We didn't talk about what movie star was in town, and how well were the grosses of the last picture. Literally, I never heard anything about any of that at all. I was rather just buzzed to discover that my uncle ran a movie studio. I didn't really know. It was very downplayed. You know, Midwestern Jews keep a low profile."

Still, he must have picked up some kind of ambitious pluck: While still an undergrad at Colgate University in New York, Balaban essentially talked his way into getting an agent to submit him for the role of Linus in the off-Broadway debut of the musical You're a Good Man Charlie Brown — and he landed the part.

"I got jobs quickly," he said. "I was strangely aggressive for somebody who didn't really seem like they would be."

That aggression landed Balaban his first film role in what would become an iconic, Oscar-award winning, and highly controversial film — and Balaban's role had him at the center of the controversy. He graciously walked me through his memories and insights from that experience, as well as 22 other films and TV shows he's worked on over the course of his remarkable career. Here they are, in his own lightly edited words.

Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Conventional showbiz wisdom says Balaban's first film role — for a film about a wide-eyed Texan (Jon Voight) who moves to New York City to become a male prostitute — would have derailed his entire career. But Balaban did not see it that way — and still doesn't.

I go down on Jon Voight. The character does. Was it shocking to be doing that? I was so naïve! It didn't occur to me. It was just acting. It was respectable. It wasn't a porn movie. Dustin Hoffman was in the movie, and John Schlesinger was a famous director. It did not occur to me for a second that this was anything shocking. But I guess it was shocking, and the movie got an X rating for my scene basically — and then the X rating mysteriously went away when it won the Academy Award for Best Picture. I know this is even more absurd — I was a little unaware of what I was auditioning for, and I thought perhaps it was a television movie. Now that's really strange. I guess I was just Pollyanna.

It had no effect on anything [in my career]. I mean, it wasn't like, Oh, you can only be up for gay roles now that you've done this. It was kind of a not very large part, and I wasn't the star of the movie. I suppose if I really wanted to be a movie star, or was able to be a movie star, this might have put a little ding in my movie stardom. But I was always just a character actor.

Catch-22 (1970)

Balaban's second film role was arguably more intimidating, since the adaptation of Joseph Heller's lauded WWII novel costarred Alan Arkin, Art Garfunkle, Buck Henry, Bob Newhart, Anthony Perkins, Martin Sheen, Jon Voight, and the legendary filmmaker Orson Welles. But it was an actor who wasn't in the film who stands out most in Balaban's memory.

I feel I dreamt this. Nobody remembers it. We were shooting in this little minute village, gorgeously beautiful but literally there was nothing there. And I think John Wayne flew his private plane in to the airstrip they had built for the set, and nobody came out to greet him. And then he came to the hotel and he got drunk and sort of beat up the bar. I think that happened, but, in fact, now, it's so many years later that I think I dreamt it. I'm not sure.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

François Truffaut and Balaban in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (left); Richard Dreyfuss, Truffaut, Balaban, and Steven Spielberg on the set (right).

Balaban got to work with two great directors on this sci-fi masterpiece — the film's writer-director, Steven Spielberg, and French New Wave pioneer François Truffaut, who played a French scientist tracking down reports of alien abductions, with Balaban playing his interpreter. He parlayed the experience into the book Spielberg, Truffaut & Me: An Actor's Diary, which happened almost by accident.

I wrote letters home to my wife, and occasionally told stories about the movie in these letters. Don't forget these are the days you wrote to people sometimes. When I got back, I was having a baby, I was 30, [and] I hadn't finished graduating college, so I decided I would get my college degree. I cobbled together some sociology course which I didn't have to attend because I was working a lot — all I had to do was write a paper that was like 100 pages and never go to class. So I made up a paper called "Social Stratification on a Film Set" and wrote 100 pages on what it was like in Close Encounters in terms of how people got treated.

I was at a party, and happened to mention exactly what I'm telling you to somebody, and there was a gossip columnist listening who put in the paper the next day that I had the behind-the-scenes, tell-all diary of the greatest, most amazing movie in the world. I got three calls to publish it, but I had not written it. This whole thing got sold and packaged on the fact that I would have to write this book in a week, which I did! And that's how it happened.

I did get approval on it. I sent it to Steven Spielberg, and I sent a chapter on it to Truffaut. And I said, 'If it feels invasive, I just won't publish it.' And Steven said, 'No! In fact, I'll write the introduction! We'll use it as the making-of-the-movie book!'

I would never do it twice. I would never want to be known as the actor on the set that you can't be comfortable in front of.

Prince of the City (1981) and Parents (1989)

Balaban made his feature directorial debut with the my-folks-might-be-cannibals horror flick Parents, but he took an unusual path to get there.

I directed a play at the Public Theatre, and I decided I hated directing and I mustn't think about being a director. Then I worked with Sidney Lumet in The Prince of the City. When it was over, I asked if I could apprentice myself to him to learn how to be a movie director. I don't know why. I just thought this would be a terrible opportunity to waste. After I turned down a lead in a Broadway show while I was apprenticing myself to Sidney, I thought, I really made a sacrifice. I must care about being a director.

Parents, I read that movie, and I went, 'Oh, I know this little boy, it's me when I was little.' It's not a great movie, but I had a real connection to it. I really did learn something from it: I try to remember how I felt it when I first read it or saw it, and I try to hold on to that. I learned from Parents to trust your instincts if you get excited about something. It might not be good, but at least you'll be passionate about it.

My Boyfriend's Back (1993)

Balaban's next film as a director was far less personal to him, and his experience on it suffered as a result.

My Boyfriend's Back, a teenage comedy about a boy who becomes a zombie and takes his girlfriend to the prom, is a middle-of-the-road Hollywood product thing. It sort of had vaguely cute potential, and it got squished into, you know, 'Make sure you don't move the camera, because then we can't recut all of your scenes! Don't add too much contrast! Oh, that actress is a little too old — she can't play the great grandmother!' I mean, you couldn't do anything more mainstream than that. The sad thing about it is I did it because I could not get any other directing jobs. I wasn't smart enough to realize I had to create my own opportunities at that point. It was very, very diminishing, that experience. I learned after it that I had really better only do things because I like them, and not because it sounds like a good idea because I'll get a career from it.

One silver lining from the experience: Balaban directed Philip Seymour Hoffman in one of his earliest film roles.

Phil was a cast as a football hero who gets eaten by the zombie. It wasn't a large part, but it was a real part, and he was obviously delightful and sweet and wonderful. He came up to me at some point in a break in the shooting and said, 'Bob, I want you to know, I don't always play football heroes who get eaten by zombies. I can basically do anything.' He said it in the simplest, sweetest way. It just made me think he was an endearing person who really knows what he can do. He said, 'I can be romantic, I can be adventurous, I can be the bad guy, I can be the good guy. I really can do anything, so please remember that. Don't forget.'

I'd never been spoke to that way by anybody. And it didn't have an ounce of ego in it.

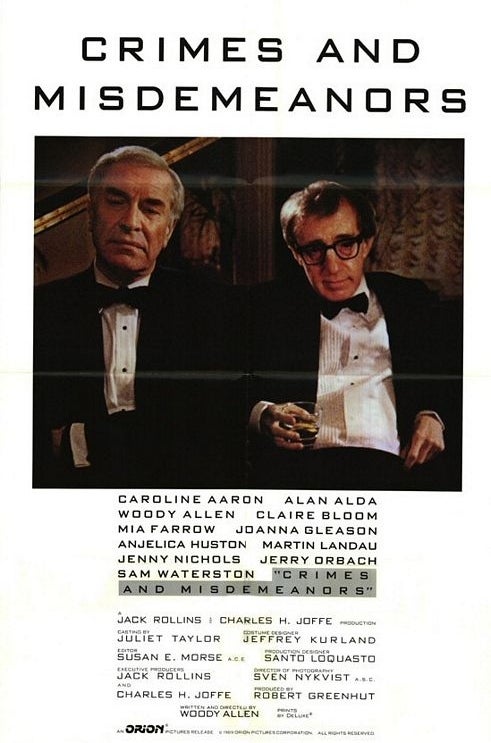

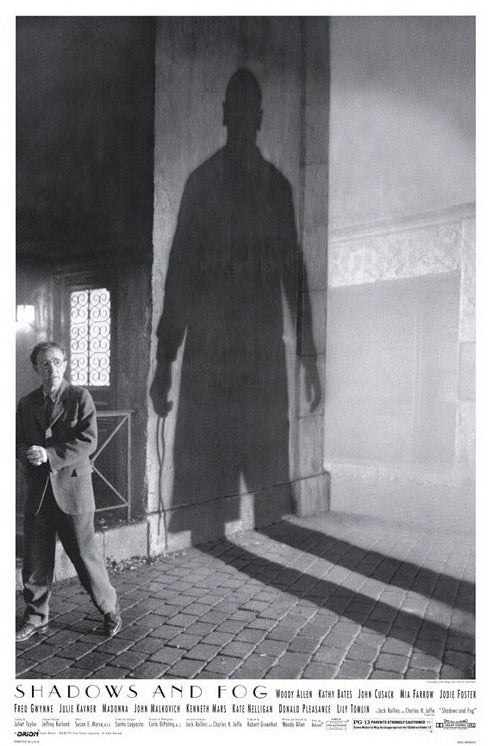

Alice (1990) and Deconstructing Harry (1997)

As was the case with so many New York-based actors in the 1980s and '90s, Balaban ended up working with Woody Allen four times — although only two of his performances made it to theaters.

The first time I worked with Woody, I had a really fun nice part in Crimes and Misdemeanors. Caroline Aaron, who played Woody's sister in the movie, had a series of horrible, degrading dates. Only one remains in the movie, the first date, in which she says, "My date shat on me," and he says, "Well, you know, guys do that," and she said, "No, literally, he shat on me." In the script, the dates got worse and worse, and finally I'm her dream date near the end of the movie. I had a great time. I'd heard these stories about, "Oh, you'll feel nervous, you won't feel like Woody likes you." But I thought, "There's something wrong with me. I feel happy. I feel like he likes me and I'm fine." Then somebody said, "Well, Woody wanted you to know you did well and he liked you, but there's no room for [your] story." I was cut.

Then I was in Alice. I have a little three- or four-minute part that's one of the more fun times I ever had in a movie. I fall in love with Mia Farrow and I've taken a magic potion and I propose to her in one little scene. It's really cute.

Then I was in Shadows and Fog. I wasn't very good, actually, and I was cut. I guess I just was miscast or something. I actually went to the premiere of the movie and I said to my wife, "Oh, look, I'm going to walk out that door now," and it was Wallace Shawn instead of me. Which was totally fine, I don't require to be told — unless I was the star of the movie, and then I'd have a heart attack.

Then I was in Deconstructing Harry, in which case, I worked on the movie for a couple of months, and I really had fun, and I liked the movie a lot. I had four all good experiences with differing results.

Balaban's experiences bracket what has become known as "Mia-gate," i.e. the twin scandals of Allen's affair with Mia Farrow's adopted teenage daughter Soon-Yi Previn, and the allegations that Allen molested Farrow's much younger daughter Dylan Farrow, both of which first emerged in 1992.

I can't even think about it. I'm afraid I can't give you any exciting or interesting things to say, other than god knows what to think about the whole thing. He's made equally wonderful movies since, and to me seemed very similar. He's married now, and he has more children. But I haven't noticed a change with him. He seems happy and well. And he always did.

Seinfeld (1992-1993) and The Late Shift (1996)

Julia Louis-Dreyfus and Balaban in Seinfeld (left); Balaban in The Late Shift (right).

One of the more peculiar parts of Balaban's resume is that he essentially played former NBC head Warren Littlefield twice — once, as a fictionalized version of Littlefield on Seinfeld, and again as Littlefield himself in the TV movie version of the battle between Jay Leno and David Letterman to replace Johnny Carson, The Late Shift.

The odd thing about it is I was friends with Warren Littlefield. I knew him when he was an independent producer, and there I was having a fair amount of screen time being him. For Seinfeld, frankly, I didn't realize I was supposed to be Warren, exactly. There was nothing about my character that really was like Warren. I was just the head of NBC. But when The Late Shift came around, I actually asked Warren if I could study him, like I studied Sidney Lumet. I spent a full day in his office, sitting in the back, while people came in and had meetings with him. I wasn't trying to physically impersonate him, but I did learn a lot about being in power and stuff. Warren is not a schmuck-y stereotype — he's a thoughtful, sensible executive. But years later, somebody came up to me, a successful writer, and said, "You ruined my meeting with Warren! It's very scary to go in there and know that there's an actor watching everything that's happening. And then Warren acted differently, because you were watching him, so he wasn't exactly Warren with me."

Waiting for Guffman (1996), Best in Show (2000), A Mighty Wind (2003), and For Your Consideration (2006)

As a teenager, Balaban participated in some of the earliest classes in improv comedy at Chicago's Second City theater, so he was especially well prepared to join what became a regular company of actors performing in a series of improvisational comedies directed by Christopher Guest.

There's no script, as you know. There's an outline, and the outline is not a Larry David outline. I've read those. Larry David has a very well-thought-out outline. The little plot points wander through it. He loses the red hat in the first scene, and on the fourth scene, it turns up on a donkey. It's really complicated.

On A Mighty Wind, [the script] said, 'Bob and Michael Hitchcock watch the scenery being loaded in.' That's the scene where we watch the microphones. Then it would say, 'Bob stands by the plant in the mezzanine and speaks to Michael Hitchcock.' That's that scene. Then it says, 'Bob is on stage.' That's all it says. We did them in order, ending up on the stage. And my character had been so annoying to Michael, by simply being, you known, concerned for safety, and my character didn't know much about theater. I referred to scenery as 'furniture,' which completely surprised me — I forgot the word for scenery, I guess. I was so obsessive and so concerned about stupid things like the lights falling on people, he just attacked me! In the movie, it's the mildest little bop on the head, but when he actually came over with his clipboard to hit me on the head, I thought he was like going to knock me out or something. I fell to the ground and then we all laughed. And that was that. We only did it once.

Friends (1999)

Who else could play Phoebe's father?

I had seen Friends a couple of times, and I liked it. And Lisa Kudrow is one of my favorite people as an actor and as a person. In the script, it said that I had to sing 'Smelly Cat.' It was like, 'What's that? How do sing a cat? What is it?' I literally had no idea. It's fun to be on iconic shows, like, 'You're Phoebe's dad!' Well, I was once for five minutes, but it's fun to be a part of pop-cultural history.

Gosford Park (2001)

As his career was reaching new heights thanks to the Guest films and his TV appearances, Balaban had his first major hit as a producer with this Upstairs, Downstairs-style murder mystery, directed by the famed ensemble filmmaker Robert Altman, and written by Julian Fellowes, then a largely untested screenwriter who would go on to create the similarly themed — but slightly less murderous — Downton Abbey.

I was sitting around in my dusty little office in New York, reading Agatha Christie, thinking about how interesting it would be to see Robert Altman do an Agatha Christie movie, basically. So I went to visit Robert. Told him about it: 'It's about a bunch of rich people, it's a country weekend, somebody gets killed, and they're all suspects.' And he said, 'Well, can't we just do it all from the servant's point of view, and we'll never even see the people upstairs? I don't really like rich people all that much. I like regular people.' And I said, 'Listen, I have a feeling you're going to find it very interesting to do your version of Upstairs, Downstairs. I think it's going to be something we've never seen before.'

I knew Julian Fellowes because I had worked with him a couple years before on a [film adaptation of an] Anthony Trollope novel called The Eustace Diamonds that I had been attempting to get re-written. He was basically an actor, and I don't think he'd had anything produced as a screenwriter, but he was very anxious to do that. I knew Bob would like him because he's so smart and he's just so well prepared.

It was fascinating for me to watch how [Altman] directed the film. He's able to shoot 19 people in a room, doing lots of stuff, quickly, efficiently, and in a way that allows the actors to have their own reality during the whole thing. We had one scene in the beginning where I get introduced to all these people. My head was swirling — like, How will he ever shoot this? He's got his two cameras wandering around. We rehearsed for most of the day, and then shot seven pages in an hour. It was the easiest thing I've ever seen. You see it cut together, and it looks like somebody must have taken a week to shoot that scene.

Fellowes won an Oscar for his script, and the film was nominated for six other Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

I've produced some other things before, but of this magnitude, never, and probably never again. But going from when it's an idea in your head to talking about it, and eight months later you're sitting in England wearing your own fur coat because you're in the movie, standing with Maggie Smith and all my friends — you do sort of have to pinch yourself when stuff like that happens, because it doesn't happen much.

Capote (2005)

Balaban reunited with Hoffman, this time in front of the camera for director Bennett Miller, playing the New Yorker editor William Shawn, who helped shepherd the early version of Truman Capote's novel In Cold Blood.

The way Bennett Miller worked with him on Capote was very, very special. Obviously, Bennett knew that this was a movie about a lot of aspects of Capote's in the writing of In Cold Blood. So Phil and Bennett kept this character alive all the time while we were shooting. Bennett would say, 'Let's do the phone call again. This time, improvise a phone call. Let's do it a little differently.'

They just kept allowing Phil to live inside of Truman Capote. Every time he'd do a take, he got richer, and better.

Bernard and Doris (2006)

After My Boyfriend's Back, Balaban's directing career moved to television, working on shows like Oz in 1998, Strangers with Candy in 1999, and Now and Again in 2000. By 2006, he had a feature film script in hand about heiress Doris Duke and her gay butler that had attracted Susan Sarandon and Ralph Fiennes, and he was able to cobble together just enough money to make it.

We had $500,000, and we made a movie about the richest person in the world. Susan and Ralph were brilliant, and really good friends to stick with me through the cheapest filming experience you've ever seen. Lunch would come, and we'd have crackers on a tray. It was unbearably threadbare, but we had a really good time because, you know, real actors don't care about that stuff too much.

After all that painstaking work, rather than earn a theatrical release — after trying to send it "to, like, 900 places" — the film was picked up by HBO and released as a TV movie.

It was a consolation prize, and it turned out be so much better for all of us. HBO said, 'We want to do the full treatment — we'll redo the score, we'll pay for some stuff to be fixed here and there, and we'll present it as one of our big centerpieces.' Had I waited to try to close with some of the tiny little distribution companies who were interested in us, we never would have seen the light of day and nobody would have known it existed. I'm very happy it worked out that way, but it was not at all my plan.

Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

Playing the narrator in a Wes Anderson movie sounds like pretty much exactly the experience one would hope it would be.

When I read it, you could be anything as the narrator. Who knows? But I knew from 17,000 costume fittings that Wes had some real specific ideas about what this was going to be like. I came to Wes' house, beautiful house, and he had a little editing suite established there. And he said, 'Well, Bob, I've basically filmed a lot of your part with me in it, just to experiment, to see how it would look in the frame and what the shots would be like. Why don't I just show it to you?' He showed me Wes reading the lines, like, off of cue cards, and standing in certain places. He never had to say anything else again after that. He didn't say I should act like he acted. But as soon as I could see it, it completely told me what I had to do to be the narrator. It was so easy and so smart.

Girls (2014)

Most recently, Balaban has appeared as Hannah's therapist on the HBO show GIrls, a role for which Balaban is often selected.

I vaguely know Lena Dunham. I think Lena was looking for a therapist, and I live in New York and I'm an obvious therapist, I guess? I have evidently a persona that I'm not terribly aware of that makes people think I'm learned and scholarly, like therapists are supposed to be. I was Catherine Zeta-Jones' therapist in a movie called No Reservations, and I was the therapist who tried to talk Sam Jackson and Nicolas Cage down from a terrible thing they were doing in a comedy that wasn't that funny called Amos and Andrew. I think that there is in my bag of small tricks, a therapist somewhere, I guess.

The Monuments Men (2014)

And Balaban joined George Clooney, Matt Damon, Bill Murray, John Goodman, Jean Dujardin, and Hugh Bonneville in this tale of scholars and artists tasked with recovering tens of thousands of works of art stolen by the Nazi regime during WWII, which just passed $100 million worldwide.

I had known George, had polite and really pleasant conversations with him, for the last 10 years. I probably met him when Gosford Park got nominated. Grant Heslov and I know each other through my three sweet, nice cousins — they all went to school together. We had a nice chat about it the night of the Argo opening night party, with a fancy dinner at a steak house afterwards and it was all very lavish and nice. I talked to Grant. I saw George. I waved. The next morning, I got a call: "Would you like to be in Monuments Men?"

Everybody was really nice, and I got along and it was fun. Nobody was standoffish and nobody was clique-ish or anything. But they're all too tall. There's nowhere I could be that I wasn't looking up at them, and sometimes I couldn't even hear what they were saying because they were so high. I said to somebody the other day, "No really, they're not that tall. When I was in scenes with them, they made me be in a trench."